The Effect of Pullman Square on Downtown Huntington, West Virginia" (2008)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Mayors' Institute on City Design

The Mayors’ Institute on City Design The National Endowment for the Arts The United States Conference of Mayors The American Architectural Foundation Hosted by: The Remaking Cities Institute School of Architecture Carnegie Mellon University Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania February 10-12, 2010 MICD Midwest | February 10-12, 2010 Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania Mayors The Honorable Keith G. Bosman The Honorable Danny Jones Kenosha, Wisconsin Charleston, West Virginia The Honorable Timothy J. Davlin The Honorable Dick Moore Springfield, Illinois Elkhart, Indiana The Honorable John T. Dickert The Honorable Jay Williams Racine, Wisconsin Youngstown, Ohio The Honorable William J. Healy II The Honorable Kim Wolfe Canton, Ohio Huntington, West Virginia Resource Team Frederick R. Bonci, RLA, ASLA Walter Kulash, P.E. LaQuatra Bonci Associates Transportation Planner William Gilchrist, FAIA Dr. Deborah A. Lange, P.E., ASCE EDAW/AECOM Carnegie Mellon University The Honorable William H. Hudnut III Vivian Loftness, FAIA Urban Land Institute Carnegie Mellon University Paul Hardin Kapp, AIA, LEED AP Anne-Marie Lubenau, AIA University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Community Design Center of Pittsburgh MICD Midwest | February 10-12, 2010 Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania MICD Sponsors Ronald Bogle Tom McClimon President & CEO Managing Director American Architectural Foundation United States Conference of Mayors Washington, District of Columbia Washington, District of Columbia Tom Cochran CEO & Executive Director United States Conference of Mayors Washington, District of Columbia Rocco Landesman Chairman National Endowment for the Arts Washington, District of Columbia MICD Staff Story K. Bellows Director Washington, District of Columbia Nicholas Foster Deputy Director Washington, District of Columbia MICD Midwest | February 10-12, 2010 Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania Host Team Donald K. -

Vertical File Index, 1970S-2000

Marshall University Marshall Digital Scholar Miscellaneous Inventories Research Guides 10-2019 Vertical File Index, 1970s-2000 Marshall University Special Collections Follow this and additional works at: https://mds.marshall.edu/sc_misc_inventories Part of the Appalachian Studies Commons, Other History Commons, and the Public History Commons Marshall University Special Collections Vertical File Index Meriam-Webster defines vertical file as, “a collection of articles (pamphlets and clippings) that is maintained (as in a library) to answer brief questions or to provide points of information not easily located.” Vertical files were very popular in libraries before internet searching as a way to collate like materials found on specific subjects. The Special Collections vertical files contain clippings, pamphlets, articles, booklets and other literature that is too insignificant to catalog. This index serves as a guide to the folders contained within the collection. The bulk of this collection was curated from the 1970s-2000 and is broken into two distinct series: Pamphlet and Newspaper Clippings Biographies 2 VERTICAL FILES SUBJECT HEADING LIST (Pamphlets and Newspaper Clippings) A ARCHEOLOGY ALUMINUM – KAISER ABORTION (3 FOLDERS) AMBULANCE SERVICE ARCHEOLOGY – PETROGRAPHS ACID RAIN ANIMAL CONTROL ARCHITECHTURE ACLU ANIMALS ARTISTS – SEE ALSO Biography files for individual artists ADOPTION APPALACHIA (4 FOLDERS) (2 FOLDERS) AFSCME (American Federal, APPALACHIA – CHURCHES ASBESTAS State, County, and Municipal Employees) APPALACHIA – ECONOMIC -

Spotlight on Huntington

SPOTLIGHT ON HUNTINGTON WELCOME TO HUNTINGTON, WEST VIRGINIA Huntington is a city in Cabell and Wayne counties in the U.S. state of West Virginia, located at the confluence of the Guyandotte River and the Ohio River. Huntington is the second largest city in West Virginia. The city is the home of Marshall University as well as the Huntington Museum of Art; the Big Sandy Superstore Arena; the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (Huntington District); the Collis P. Huntington Historical Society and Railroad Museum; Camden Park, one of the world’s oldest amusement parks; the headquarters of the CSX Transportation-Huntington Division, the largest division in the CSX network; and the Port of Huntington Tri-State, the largest river port in the United States. Contents Climate and Geography 02 Cost of Living and Transportation 03 Sports and Outdoor Activities 04 Shopping and Dining 05 Schools and Education 06 GLOBAL MOBILITY SOLUTIONS l SPOTLIGHT ON HUNTINGTON l 01 SPOTLIGHT ON HUNTINGTON CLIMATE Because of its position in the westernmost Huntington, WV Climate Graph and lowest area of the state, the city is on the northern limits of a humid subtropical climate), unlike the “highlands” of West Virginia, which are in the Allegheny Mountains and the Appalachian Mountains. This location gives the city a perfect four seasons, with each season beginning around the calendar date. Huntington is made humid by the Ohio River, but summers are not as hot as they are further south and west and snowfall generally falls in moderate amounts. Average High/Low Temperatures Low / High January 25oF / 43oF July 66oF / 87oF Average Precipitation Rain 43 in. -

Cabellcounty Summerfun Flier 2

2019 Pathways To SUMMER FUN Cabell County, WV This listing of summer camps and enrichment activities have been compiled for a quick glance into all the different pathways your children and youth can explore for fun learning experiences this summer. Confirm dates, times, and details with each program. A full list with links to each program can be found at bit.ly/pathwaystosummerfun2019 and cabellfrn.org. Scan here! Funington Cabell-Huntington Convention and Visitors Bureau Discover all there is to see and do in Cabell & Wayne County. Huntington Fun For Kids offers www.visithuntingtonwv.org/what-to-do/events-calendar/ the opportunity to see, play, and explore every week day during Greater Huntington Parks and Recreation District the months of June and July Join the GHPRD Recreation Team for a fun new activity at a different park at Huntington Museum of Art, each week in the summer. For more details: www.ghprd.org Camden Park, Heritage Farm, and Greater Huntington Parks and Barboursville Park Recreation. Go to facebook.com/ Fun events for kids and families are scheduled all summer long! Funington for more information. www.facebook.com/BvilleParksRec Brought to you by: 2019 Pathways To SUMMER FUN Cabell County, WV Find Things To Do Near You! Visit bit.ly/pathwaystosummerfun2019 for the full list! 4H Camps: County 4-H camps are listed at www.extension.wvu.edu/cabell/4h and more information can be found at www.facebook.com/ WVUExtension/. For registration forms, call 304-526-8458. Arts in Action in Hurricane: Week-long activities and camps. Visit www.artsinactionwv.org or call 304-419-4446. -

HUNTINGTON MALL COMPLEX BARBOURSVILLE, WEST VIRGINIA Huntington Mall

HUNTINGTON MALL COMPLEX BARBOURSVILLE, WEST VIRGINIA Huntington Mall Interstate 64 About Huntington Mall Complex Huntington Mall is a super-regional shopping complex. It is not only the largest shopping center in the state of West Virginia, but also attracts customers from Ohio and Kentucky. It serves as the region’s hub for shopping, dining, and entertainment. Comprising over 1.5 million square feet , the mall is anchored by Macy’s, Elder-Beerman, Sears, JCPenney, Dick’s Sporting Goods, Cinemark Cinema 12-Plex and Kohl’s, along with more than 150 specialty shops, restaurants, and a hotel. The mall is currently completing an extensive renovation that incorporates major upgrades in fl ooring, new ceilings with skylights, bright, contemporary concourse styling and exterior improvements. Revised: 11/30/11 25 50 77 PORTSMOUTH GALLIA 50% 40 OH s SCIOTO 50% 52 OH •Columbusmbbus • 30 MASON 40% WheelingWWhheelheelineelini g LAWRENCE 95% 20 IRONTON PUTNAM 60% •Cincinnati s 10 WV GREENUP 80% HUNTINGTON MALL COMPLEX 64 Huntington •BarboursvilleBBaBarboursville s CABELL 100% • GRAYSON 60 CharCharleston HUNTINGTON •Lexington s BOYD 100% CHARLESTONs VA CARTER 50% BeckleyBeckBeecklcklklekklleyleeyy WAYNE 75% LINCOLN 50% LAWRENCE 50% 119 •LynchburgLynynchburc g KY KY 23 WV •WythevilleWytheville Trade Area Map Trade Area Trade Area Population 383,966 Average Household Income $50,823 Number of Households 156,580 Median Age 40 Trade area data on this page is adjusted to refl ect portions of counties in the trade area. Data Source: Scan/US 2010 , 2010 Edition of Editor & Publisher Market Guide. Huntington Mall Facts Opening Date 1981 Renovation Date 2011 Total Complex Size 1.5 million + sq.ft. -

The Parthenon, September 19, 2018

Marshall University Marshall Digital Scholar The aP rthenon University Archives 9-19-2018 The aP rthenon, September 19, 2018 Sadie Helmick [email protected] Franklin Norton [email protected] Sarah Ingram [email protected] Kieran Intemann [email protected] Heather Barker [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://mds.marshall.edu/parthenon Recommended Citation Helmick, Sadie; Norton, Franklin; Ingram, Sarah; Intemann, Kieran; and Barker, Heather, "The aP rthenon, September 19, 2018" (2018). The Parthenon. 737. https://mds.marshall.edu/parthenon/737 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the University Archives at Marshall Digital Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in The aP rthenon by an authorized administrator of Marshall Digital Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. WEDNESDAY, SEPTEMBER 19, 2018 | VOL. 122 NO. 61 | MARSHALL UNIVERSITY’S STUDENT NEWSPAPER | marshallparthenon.com | SINGLE COPY FREE Cabell-Wayne animal shelter seeking volunteers WHAT’S INSIDE READ MORE ON PAGE 2 Transgender3 group Huntington’s4 Kitchen Collection5 for a cause MU v.6 NC State on Williams7 sisters at EDITORIAL:8 Smirl9 Meets World 12Starbucks bike Science grant SGA senate meeting Red flag campaign Saturday Greenbriar Mac Miller Red head rep Marshall smashers PAGE EDITED AND DESIGNED BY SADIE HELMICK | [email protected] Marshall students Running Six Days a Week! FRIDAY & ride FREE with I.D. Standard Daytime Service: SATURDAY 20-minute loop along 3rd, 4th and 5th Avenues 529-RIDE between 7:30am & 5:00pm LATE NIGHT Stops at Pullman Square (Visual Arts Center, Friday: Huntington’s Kitchen), Keith Albee & More! 7:30am-3am DOWNLOAD ROUTESHOUT Evening service: 30-minute loop, route extended to include Saturday: WWW.TTA-WV.COM 5th Avenue Kroger from 5:00pm to 11:30pm 3pm-3am 378381 (304) 529-7433 2 WEDNESDAY, SEPTEMBER 19, 2018 MARSHALLPARTHENON.COM Cabell-Wayne Animal Shelter in need of volunteers By LILLIE BODIE there vetting completed. -

The Parthenon, September 12, 2018

Marshall University Marshall Digital Scholar The aP rthenon University Archives 9-12-2018 The aP rthenon, September 12, 2018 Sadie Helmick [email protected] Sarah Ingram [email protected] Rick Farlow [email protected] Franklin Norton [email protected] Heather Barker [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://mds.marshall.edu/parthenon Recommended Citation Helmick, Sadie; Ingram, Sarah; Farlow, Rick; Norton, Franklin; and Barker, Heather, "The aP rthenon, September 12, 2018" (2018). The Parthenon. 736. https://mds.marshall.edu/parthenon/736 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the University Archives at Marshall Digital Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in The aP rthenon by an authorized administrator of Marshall Digital Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. WEDNESDAY, SEPTEMBER 12, 2018 | VOL. 122 NO. 60 | MARSHALL UNIVERSITY’S STUDENT NEWSPAPER | marshallparthenon.com | SINGLE COPY FREE Marshall students react to WHAT’S INSIDE free Wi-Fi downtownREAD MORE ON PAGE 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 12 Diversity lecture Money in politics SGA meeting Herd tops EKU MU versus SC EDITORIAL: LET ME BE FRANK Recovery through debate Saturday Woodward Smirl Meets World worship PAGE EDITED AND DESIGNED BY SADIE HELMICK | [email protected] Marshall students Running Six Days a Week! FRIDAY & ride FREE with I.D. Standard Daytime Service: SATURDAY 20-minute loop along 3rd, 4th and 5th Avenues 529-RIDE between 7:30am & 5:00pm LATE NIGHT -

Best Buy Has Approximately 1,500 Stores Across North America, Generating $42.15 Billion in Revenue for Fiscal 2018 (Ended Feb

OFFERING MEMORANDUM 6 Mall Road | Barboursville, WV 25504 Actual Property Image INVESTMENT SUMMARY 03 • Investment Summary • Investment Highlights • Est. Operating Info AREA OVERVIEW • Location Map 06 Actual Property Image • Aerial & Retail Maps • City Overview Exclusively Marketed By: Sands Investment Group TENANT OVERVIEW Adam Scherr Max Freedman 10 • Tenant Profile Lic. # 01925644 Lic. # 644481 310.853.1266 | DIRECT 512.766.2711 | DIRECT LEASE ABSTRACT [email protected] [email protected] 11 • Lease Summary • © 2018 Sands Investment Group (SIG). The information contained in this ‘Offering Memorandum,’ has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable. Sands Investment Rent Roll Group does not doubt its accuracy, however, Sands Investment Group makes no guarantee, representation or warranty about the accuracy contained herein. It is the responsibility of each individual to conduct thorough due diligence on any and all information that is passed on about the property to determine it’s accuracy and completeness. Any and all projections, market assumptions and cash flow analysis are used to help determine a potential overview on the property, however there is no guarantee or assurance In Cooperation with Rockstar Realty, LLC these projections, market assumptions and cash flow analysis are subject to change with property and market conditions. Sands Investment Group encourages all potential BoR: Paul Napoli (WV0023831) / Nancy McBride WV0002673) interested buyers to seek advice from your tax, financial and legal advisors before making any -

Exit 8 / I-64 Mixed Use Development and Traffic Mobility Study

DRAFT STUDY KYOVA Exit 8 / I-64 Mixed Use Development and Traffic Mobility Study Prepared for: KYOVA Interstate Planning Commission 400 Third Avenue Huntington, WV 25701 www.kyovaipc.org Prepared by: in association with: November 2018 EXIT 8/I-64 MIXED-USE DEVELOPMENT AND FINAL REPORT NOVEMBER 2018 TRAFFIC MOBILITY STUDY TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ........................................................................................................................................................................................ 1 Purpose and Need ........................................................................................................................................................................ 6 Existing Conditions ............................................................................................................................................................................ 7 Regional Planning Documents ..................................................................................................................................................... 7 BEECH FORK LAKE ACCESS ROAD STUDY .................................................................................................................. 7 Heritage Farm Museum and Village Access Road Study ................................................................................................... 8 Statewide Freight Plan ................................................................................................................................................................. -

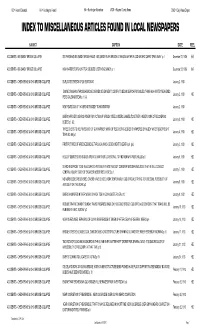

Copy of Huntington History Index 6-7-10.Xlsx

HD = Herald Dispatch HH = Huntington Herald HA = Huntington Advertiser WCN = Wayne County News DND = Daily News Digest INDEX TO MISCELLANEOUS ARTICLES FOUND IN LOCAL NEWSPAPERS SUBJECT CAPTION DATE REEL ACCIDENTS - BIG SANDY BRIDGE COLLAPSE SIX PERISH AS BIG SANDY BRIDGE FALLS : BIG SANDY RIVER BRIDGE AT KENOVA AFTER FLOOD WATERS CARRY SPAN AWAY p. 1 December 22, 1926 HA ACCIDENTS - BIG SANDY BRIDGE COLLAPSE HIGH WATER STOPS HUNT FOR 5 BODIES LOST IN BIG SANDY p. 1 December 23, 1926 HA ACCIDENTS - CHESAPEAKE & OHIO BRIDGE COLLAPSE DUPLICATES WRECK OF 20 YEARS AGO January 2, 1913 ENGINE CRASHING THROUGH BRIDGE CARRIES SEVEN MEN TO DEATH; TO BEGIN SEARCH FOR BODIES: THINK HIGH WATER WEAKENED ACCIDENTS - CHESAPEAKE & OHIO BRIDGE COLLAPSE January 2, 1913 HD PIERS CAUSING BREAK p. 1 & 3 ACCIDENTS - CHESAPEAKE & OHIO BRIDGE COLLAPSE NEW YEARS DAY OF 1913 BRING TRAGEDY TO HUNTINGTON January 2, 1913 DIVERS ARRIVE TO SEARCH RIVER FOR VICTIMS OF WRECK: STEEL GIRDERS JAMMED TOGETHER, HINDER WORK OF RECOVERING ACCIDENTS - CHESAPEAKE & OHIO BRIDGE COLLAPSE January 3, 1913 HD BODIES p.1 & 2 THREE DIVERS TO HELP IN SEARCH OF GUYAN RIVER: WORK OF RECOVERING BODIES IS HAMPERED BY MUDDY WATER [C&O FREIGHT ACCIDENTS - CHESAPEAKE & OHIO BRIDGE COLLAPSE January 4, 1913 HD TRAIN NO. 99] p.1 ACCIDENTS - CHESAPEAKE & OHIO BRIDGE COLLAPSE FIRST PICTURES OF WRECKED BRIDGE THROUGH WHICH SEVEN WENT TO DEATH p.6 (pic) January 5, 1913 HD ACCIDENTS - CHESAPEAKE & OHIO BRIDGE COLLAPSE HELD BY DEBRIS SEVEN BODIES ARE IN GUYAN RIVER...DIVERS FAIL TO FIND MEN WHO WERE -

West Virginia Opportunity Zones Pitchbook

A Pitch for Opportunity Zone Investments Key projects, properties & sectors for economic development & Opportunity Fund investments in the Advantage Valley region of West Virginia, home to the State Capitol of Charleston, the economic powerhouse Huntington, the commercial hub South Charleston, and prime development and manufacturing targets in Boone, Jackson and Mason Counties. Advantage Valley is a coordinated economic region with 13 designated Opportunity Zones, 20 key growth sectors and dozens of real estate, development & business opportunities ready for investment. This Advantage Valley Opportunity Pitch book is for developers, business investors and Opportunity Fund managers. The Pitch book describes the region and its economic opportunities, highlights the competitive advantages of its key localities and their Opportunity Zones, identifies 20+ development projects ready for investment, and tells you how to get in touch with us as we move Opportunity Funds into action. Purposes of Pitch Book ! Convey the opportunity for development & investment in the Advantage Valley, WV region ! Articulate the opportunities in 13 Opportunity Zones to help investors make informed decisions ! Highlight 20 specific investible projects located in Pullman Square, Huntington, WV Advantage Valley’s designated Opportunity Zones ! Pitch developers, business owners & investors in the region to move forward on investment-ready projects and consider creating single-asset Opportunity Funds to move these projects forward ! Attract Opportunity Fund managers -

Tri-State Data an Economic Development Resource

Tri-State Data An Economic Development Resource Table of Contents ABOUT THIS REPORT .............................................................................................................................. 4 DEMOGRAPHIC CHARACTERISTICS ................................................................................................. 5 POPULATION AND AGE ................................................................................................................................ 5 HOUSEHOLDS AND INCOME ......................................................................................................................... 6 NET MIGRATION ......................................................................................................................................... 7 EDUCATIONAL ATTAINMENT ...................................................................................................................... 8 LABOR FORCE CHARACTERISTICS ................................................................................................... 9 CIVILIAN LABOR FORCE UNEMPLOYMENT RATE, 1997-2002 ..................................................................... 9 EMPLOYMENT BY PLACE OF WORK ............................................................................................................. 9 EMPLOYMENT BY OCCUPATION ................................................................................................................ 10 PLACE OF WORK ......................................................................................................................................