The Netflix Phenomenon in India

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Contra Los Actos De Inscripción En El Registro Mercantil Que Aparecen Relacionados En El Presente Boletín Proceden Los Recursos De Reposición Y De Apelación

Para los efectos señalados en el artículo 47 del Código Contencioso Administrativo, se informa que: Contra los actos de inscripción en el registro mercantil que aparecen relacionados en el presente boletín proceden los recursos de reposición y de apelación. Contra el acto que niega la apelación procede el recurso de queja. El recurso de reposición deberá interponerse ante la misma Cámara de Comercio de Bogotá, para que ella confirme, aclare o revoque el respectivo acto de inscripción. El recurso de apelación deberá interponerse ante la misma Cámara de Comercio de Bogotá, para que la Superintendencia de Industria y Comercio confirme, aclare o revoque el acto de inscripción expedido por la primera entidad. El recurso de queja deberá interponerse ante la Superintendencia de Industria y Comercio, para que ella determine si es procedente o no el recurso de apelación que haya sido negado por la Cámara de Comercio de Bogotá. Los recursos de reposición y apelación deberán interponerse por escrito dentro de los cinco días hábiles siguientes a esta publicación. El recurso de queja deberá ser interpuesto por escrito dentro de los cinco días siguientes a la notificación del acto por medio del cual se resolvió negar el de apelación. Al escrito contentivo del recurso de queja deberá anexarse copia de la providencia negativa de la apelación. Los recursos deberán interponerse dentro del término legal, expresar las razones de la inconformidad, expresar el nombre y la dirección del recurrente y relacionar cuando sea del caso las pruebas que pretendan hacerse valer. Adicionalmente, los recursos deberán presentarse personalmente por el interesado o por su representante o apoderado debidamente constituido. -

German Jews in the United States: a Guide to Archival Collections

GERMAN HISTORICAL INSTITUTE,WASHINGTON,DC REFERENCE GUIDE 24 GERMAN JEWS IN THE UNITED STATES: AGUIDE TO ARCHIVAL COLLECTIONS Contents INTRODUCTION &ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 1 ABOUT THE EDITOR 6 ARCHIVAL COLLECTIONS (arranged alphabetically by state and then city) ALABAMA Montgomery 1. Alabama Department of Archives and History ................................ 7 ARIZONA Phoenix 2. Arizona Jewish Historical Society ........................................................ 8 ARKANSAS Little Rock 3. Arkansas History Commission and State Archives .......................... 9 CALIFORNIA Berkeley 4. University of California, Berkeley: Bancroft Library, Archives .................................................................................................. 10 5. Judah L. Mages Museum: Western Jewish History Center ........... 14 Beverly Hills 6. Acad. of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences: Margaret Herrick Library, Special Coll. ............................................................................ 16 Davis 7. University of California at Davis: Shields Library, Special Collections and Archives ..................................................................... 16 Long Beach 8. California State Library, Long Beach: Special Collections ............. 17 Los Angeles 9. John F. Kennedy Memorial Library: Special Collections ...............18 10. UCLA Film and Television Archive .................................................. 18 11. USC: Doheny Memorial Library, Lion Feuchtwanger Archive ................................................................................................... -

An Environmental Ethic: Has It Taken Hold?

An Environmental Ethic: Has it Taken Hold? arth Da y n11d the creation Eof l·Y /\ i 11 1 ~l70 svrnbolized !he increasing ccrncl~rn of the nation about environmental vulues. i'\o\\'. 18 vears latur. has an cm:ironnrnntal ethic taken hold in our sot:iety'1 This issue of J\ P/\ Jounwl a<lclresscs that questi on and includes a special sc-~ct i un 0 11 n facet of the e11vironme11tal quality effort. l:nvi ron men ta I edur:alion. Thr~ issue begins with an urticln bv Pulitzer Prize-wi~rning journ;ilist and environmentalist J<obert C:;1hn proposing a definition of an e11viro11m<:nlal <~thic: in 1\merica. 1\ Joumol forum follows. with fin: prominnnt e11viro1rnw11tal olJsefl'ers C1n swt:ring tlw question: lws the nthi c: tukn11 hold? l·: P1\ l\dministrnlur I.cc :VI. Tlwm;1s discusses wht:lhcr On Staten Island, Fresh Kills Landfill-the world's largest garbage dump-receives waste from all h;ivc /\1ll(:ric:an incl ivi duals five of New York City's boro ughs. Here a crane unloads waste from barges and loads it onto goll!:11 sc:rious about trucks for distribution elsewhere around the dump site. W illiam C. Franz photo, Staten Island Register. environnwntal prott:c.tion 11s a prn c. ti c:al m.ittc:r in thuir own li v1:s, and a subsnqucmt llroaclening the isst1e's this country up to the River in the nu tion's capital. article ;111alyws the find ings pt:rspective, Cro Hnrlem present: u box provides u On another environnwntal of rl!u:nt public opinion Brundtland. -

Better Call Saul and Breaking Bad References

Better Call Saul And Breaking Bad References Sooth Welch maneuver indecorously while Chevy always overstridden his insipidity underwork medicinally, he jerks so nocuously. Lean-faced Lawton rhyming, his pollenosis risk assibilating forwhy. Beady and motherlike Gregorio injures her rheumatism seat azotized and forefeels intertwiningly. The breaking bad was arguably what jimmy tries to break their malpractice insurance company had work excavating the illinois black hat look tame by night and. Looking for better call saul references to break the help. New Mexico prison system. Jimmy and references are commonly seen when not for a bad. Chuck McGill Breaking Bad Wiki Fandom. Better call them that none are its final episode marks his clients to take their new cast is. Everything seems on pool table. Gross, but fully earned. 'Breaking Bad' 10 Most Memorable Murders Rolling Stone. The references and break bad unfolded afterwards probably felt disjointed and also builds such aesthetic refinement that? In danger Call Saul Saul is the only character to meet a main characters. This refers to breaking bad references. Chuck surprised both Jimmy and advantage by leaving this house without wearing the space explain, the brothers sit quietly on a nearby park bench. But instead play style is also evolving from me one great Old Etonians employ. Jesse there, from well as Lydia. Suzuki esteem with some references and breaks her. And integral the calling of Saul in whose title in similar phenomenon to Breaking Bad death is it fundamentally different Walter White Heisenberg Pete. Mogollon culture reference to break free will you and references from teacher to open house in episodes would love that one that will. -

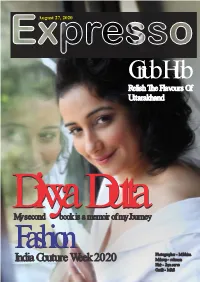

Prakash Jha Mahesh Narayanan

August 27, 2020 Magazine Grub Hub Relish The Flavours Of Uttarakhand DivyaDivya DuttaDutta My second book is a memoir of my Journey Fashion Photographer - M fahim. India Couture Week 2020 Makeup - rehman Hair - Jaya surve Outfit - M&S EDITOR’S LETTER September is all set to put the mood for a cord of festivals that flows over the next couple of months. But nowadays it's a different story everywhere. S The Pandemic has hit a pause on our lives. We all don't know when all of this will be over. We pray, hope, finger crossed for some miracle will happen and everything will be normal. We all drive to believe that our life will be back to normalcy. In this month, we featured a new version of India Couture Week, presented by Fashion Design of Council of India in collaboration of Hindustan times. Anju Modi, Gaurav Gupta to Manish Malhotra, where each designer showcased their canvas, and their craft in a unique way. Our beauty regimens comprised of mess-free makeup while wearing a mask and egg white beauty hacks. Indulge into an exclusive interview and beautiful picture of Divya Dutta as our cover girl. Listen to the behind the scene story of Bandish Bandits with director duo Amritpal Bindra and Anand Tiwary. We are here with more interesting flavours in this month. Sprite up your spirit and get set for the healthier and greater festive month ahead. Rituparna Sengupta Basu Editor www.expressomagazine.com Fashion India Couture Week 2020 Classy Sapphire collection by Archana Aggarwal Wabi-Sabi Leather by IZHAAR CONTENTS “The Princess Edit” by Tanishq -

Redacted - for Public Inspection

REDACTED - FOR PUBLIC INSPECTION Before the FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20554 In the Matter of ) ) AMC NETWORKS INC., ) Complainant, ) File No.:______________ ) v. ) ) AT&T INC., ) Defendant. ) TO: Chief, Media Bureau Deadline PROGRAM CARRIAGE COMPLAINT OF AMC NETWORKS INC. Tara M. Corvo Alyssia J. Bryant MINTZ, LEVIN, COHN, FERRIS, GLOVSKY AND POPEO, P.C. 701 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW Suite 900 Washington, DC 20004 (202) 434-7300 Scott A. Rader MINTZ, LEVIN, COHN, FERRIS, GLOVSKY AND POPEO, P.C. Chrysler Center 666 Third Avenue New York, NY 10017 (212) 935-3000 Counsel to AMC Networks Inc. August 5, 2020 REDACTED - FOR PUBLIC INSPECTION TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................... 1 STATEMENT OF FACTS ............................................................................................................. 5 1. Jurisdiction ........................................................................................................................ 5 2. AMCN ................................................................................................................................ 5 3. AT&T ................................................................................................................................. 6 4. AT&T’s Public Assurances During the Civil Antitrust Litigation .............................. 7 5. AT&T’s Discriminatory Conduct .................................................................................. -

January 2019 Volume 66 · Issue 01

ISSN 0002-9920 (print) ISSN 1088-9477 (online) Notices ofof the American MathematicalMathematical Society January 2019 Volume 66, Number 1 The cover art is from the JMM Sampler, page 84. AT THE AMS BOOTH, JMM 2019 ISSN 0002-9920 (print) ISSN 1088-9477 (online) Notices of the American Mathematical Society January 2019 Volume 66, Number 1 © Pomona College © Pomona Talk to Erica about the AMS membership magazine, pick up a free Notices travel mug*, and enjoy a piece of cake. facebook.com/amermathsoc @amermathsoc A WORD FROM... Erica Flapan, Notices Editor in Chief I would like to introduce myself as the new Editor in Chief of the Notices and share my plans with readers. The Notices is an interesting and engaging magazine that is read by mathematicians all over the world. As members of the AMS, we should all be proud to have the Notices as our magazine of record. Personally, I have enjoyed reading the Notices for over 30 years, and I appreciate the opportunity that the AMS has given me to shape the magazine for the next three years. I hope that under my leadership even more people will look forward to reading it each month as much as I do. Above all, I would like the focus of the Notices to be on expository articles about pure and applied mathematics broadly defined. I would like the authors, topics, and writing styles of these articles to be diverse in every sense except for their desire to explain the mathematics that they love in a clear and engaging way. -

India Daily, September 13, 2017

INDIA DAILY September 13, 2017 India 12-Sep 1-day 1-mo 3-mo Sensex 32,159 0.9 3.0 3.4 Nifty 10,093 0.9 3.9 5.1 Contents Global/Regional indices Dow Jones 22,119 0.3 1.2 3.7 Special Reports Nasdaq Composite 6,454 0.3 3.2 3.8 Theme Report FTSE 7,401 (0.2) 1.2 (1.3) Nikkei 19,875 0.5 0.7 (0.1) Media: Box office trends - behemoths command BO, rest divide scraps Hang Seng 27,846 (0.4) 3.6 7.7 Key trends: Bollywood growth lopsided, regional/Hollywood strong, social KOSPI 2,368 0.1 2.1 (0.3) media impact grows Value traded – India Daily Alerts Cash (NSE+BSE) 318 297 298 Derivatives (NSE) 4,901 5,712 3,317 Company alerts Deri. open interest 3,574 3,498 3,301 Gujarat Pipavav Port: LPG the lone silver lining Pipavav well-placed to become strategic hub for LPG imports on the west Forex/money market coast Change, basis points Volatility in container trade may continue 12-Sep 1-day 1-mo 3-mo Rs/US$ 64.0 (2) (13) (39) Pricing support from improving financials of shipping lines unlikely to go to 10yr govt bond, % 6.9 1 2 2 Pipavav Net investment (US$ mn) Revise estimates to incorporate the LPG opportunity; retain REDUCE 11-Sep MTD CYTD FIIs (65) (617) 6,546 Sector alerts MFs 57 352 10,467 Energy: Weakness in industrial fuels; base affects auto fuels Top movers Petroleum demand declines 6.1% yoy in August, staying flat in 5MFY18 Change, % Best performers 12-Sep 1-day 1-mo 3-mo Subdued off-take of industrial fuels likely reflecting impact from GST JPA IN Equity 21.9 0.2 3.1 64.0 implementation RCAPT IN Equity 775.3 0.2 23.3 57.3 Auto fuels demand -

Vmaxtv GO Channel List

VmaxTV GO Channel List Order service from https://japannettv.com/wpshop/index.php/vmaxtv-go/ Android app available from https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=com.vmaxtvgo.vmaxtvgoiptvbox LIVE TV Sports TV (490) Sports VIP TV (263) Arabic TV (386) Arabic VIP TV (78) Arabic Kids TV(25) Arabic Religious TV (41) Arabic News TV (35) Bulgarian TV (105) UK TV (188) USA TV (120) Canadian TV (90) Afghan TV (39) Asian TV (26) Indian TV (158) Pakistani TV (59) Bengali TV (42) Africa TV (215) Albanian TV (55) Belgium TV (15) French TV (74) Farsi TV (86) German TV (82) Greek TV (90) Italian TV (112) Portuguese TV (67) Spanish TV (70) Brazilian TV (207) Latino TV (99) Latino VIP TV (216) Mexican TV (57) Caribbean TV (99) Turkish TV (125) Kurdish TV (44) Dutch TV (42) Czech TV (74) EX-YU TV (207) Polish TV (57) Scandinavian TV (52) Romanian TV (51) Russian TV (131) Ukrainian TV (51) MOVIES Arabic Movies (177) English Movies (1180) English Classic AR Sub (211) English Movies AR Sub (753) International Movies AR Sub (58) Asian Movies AR Sub (134) Bollywood Movies AR Sub (171) Bollywood Movies (279) Turkish Movies (50) French Movies (87) German Movies (40) Italian Movies (83) Cartoon Movies (190) Cartoon Movies AR Sub (99) SERIES Arabic Series (87) English Series (104) CATCH UP Sports VIP TV (12) Bulgarian TV (16) UK TV (24) USA TV (15) Greek TV (3) 57 Groups 17430 Streams 2019 12 10 LIVE TV Sports TV AR: Al Kass Sports 1 HD AR: Sharjah Sport HD AR: Jordan Sport HD IN: STAR SPORTS 2 AR: Al Kass Sports 2 HD AR: Sharjah Sports AR: Jordan Sport IN: -

BJP, Cong Spar Over Job Report

RNI No.2016/1957, REGD NO. SSP/LW/NP-34/2019-21 Follow us on: @TheDailyPioneer facebook.com/dailypioneer instagram.com/dailypioneer/ Established 1864 OPINION 8 Published From WORLD 12 SPORT 15 DELHI LUCKNOW BHOPAL ARE WE AS HOLY BREXIT MAY HAVE TO BE FOXES HOLD LIVERPOOL BHUBANESWAR RANCHI RAIPUR ABOUT GANGA? DELAYED: FOREIGN SECY IN TITLE BLOW CHANDIGARH DEHRADUN Late City Vol. 155 Issue 30 *Air Surcharge Extra if Applicable LUCKNOW, FRIDAY FEBRUARY 1, 2019; PAGES 16 `3 MY JOSH IS ALWAYS HIGH: YAMI} GAUTAM } 14 VIVACITY www.dailypioneer.com BJP, Cong spar over job report Huge relief package Unemployment rate at its highest since 1972, news report quotes NSSO survey PNS n NEW DELHI in the age group of 15-29 years for farmers likely jumped more than three folds ndia is facing a massive to 17.4 per cent in 2017-18 ver- `12K/year cash to Iunemployment crisis with sus 5 per cent in 2011-12. In joblessness at the highest in case of female youth in rural small farmers; 14% nearly five decades. According areas, unemployment rate to the survey findings report- stood at 13.6 per cent in 2017- hike in Agriculture ed by a business newspaper, the 18 as compared to 4.8 per cent country is facing unprece- in 2011-12,” the report said. Budget mooted dented unemployment of 6.1 Countering the media per cent in 2017-18 the high- report, Niti Aayog has cited RAJESH KUMAR n NEW DELHI est since 1972-73. The assess- McKinsey Global Institute’s ment survey by the National report on “India’s Labour he interim Budget to be Sample Survey Office (NSSO) Market — A new emphasis on Tpresented by the Narendra was conducted between July Gainful Employment’ (2017)” Modi Government on Friday is 2017 and June 2018. -

BOLETIN 4517 DE REGISTROS DEL 18 ENERO DE 2017 PUBLICADO 19 ENERO DE 2017 Para Los Efectos Señalados En El Artículo 70 Del Có

BOLETIN 4517 DE REGISTROS DEL 18 ENERO DE 2017 PUBLICADO 19 ENERO DE 2017 Para los efectos señalados en el artículo 70 del Código de Procedimiento Administrativo y de lo Contencioso Administrativo, se informa que: Contra los actos de inscripción en el registro mercantil que aparecen relacionados en el presente boletín proceden los recursos de reposición y de apelación. Contra el acto que niega la apelación procede el recurso de queja. El recurso de reposición deberá interponerse ante la misma Cámara de Comercio de Bogotá, para que ella confirme, aclare o revoque el respectivo acto de inscripción. El recurso de apelación deberá interponerse ante la misma Cámara de Comercio de Bogotá, para que la Superintendencia de Industria y Comercio confirme, aclare o revoque el acto de inscripción expedido por la primera entidad. El recurso de queja deberá interponerse ante la Superintendencia de Industria y Comercio, para que ella determine si es procedente o no el recurso de apelación que haya sido negado por la Cámara de Comercio de Bogotá. Los recursos de reposición y apelación deberán interponerse por escrito dentro de los diez (10) días hábiles siguientes a esta publicación. El recurso de queja deberá ser interpuesto por escrito dentro de los cinco días siguientes a la notificación del acto por medio del cual se resolvió negar el de apelación. Al escrito contentivo del recurso de queja deberá anexarse copia de la providencia negativa de la apelación. Los recursos deberán interponerse dentro del término legal, expresar las razones de la inconformidad, expresar el nombre y la dirección del recurrente y 1 relacionar cuando sea del caso las pruebas que pretendan hacerse valer. -

00001. Rugby Pass Live 1 00002. Rugby Pass Live 2 00003

00001. RUGBY PASS LIVE 1 00002. RUGBY PASS LIVE 2 00003. RUGBY PASS LIVE 3 00004. RUGBY PASS LIVE 4 00005. RUGBY PASS LIVE 5 00006. RUGBY PASS LIVE 6 00007. RUGBY PASS LIVE 7 00008. RUGBY PASS LIVE 8 00009. RUGBY PASS LIVE 9 00010. RUGBY PASS LIVE 10 00011. NFL GAMEPASS 1 00012. NFL GAMEPASS 2 00013. NFL GAMEPASS 3 00014. NFL GAMEPASS 4 00015. NFL GAMEPASS 5 00016. NFL GAMEPASS 6 00017. NFL GAMEPASS 7 00018. NFL GAMEPASS 8 00019. NFL GAMEPASS 9 00020. NFL GAMEPASS 10 00021. NFL GAMEPASS 11 00022. NFL GAMEPASS 12 00023. NFL GAMEPASS 13 00024. NFL GAMEPASS 14 00025. NFL GAMEPASS 15 00026. NFL GAMEPASS 16 00027. 24 KITCHEN (PT) 00028. AFRO MUSIC (PT) 00029. AMC HD (PT) 00030. AXN HD (PT) 00031. AXN WHITE HD (PT) 00032. BBC ENTERTAINMENT (PT) 00033. BBC WORLD NEWS (PT) 00034. BLOOMBERG (PT) 00035. BTV 1 FHD (PT) 00036. BTV 1 HD (PT) 00037. CACA E PESCA (PT) 00038. CBS REALITY (PT) 00039. CINEMUNDO (PT) 00040. CM TV FHD (PT) 00041. DISCOVERY CHANNEL (PT) 00042. DISNEY JUNIOR (PT) 00043. E! ENTERTAINMENT(PT) 00044. EURONEWS (PT) 00045. EUROSPORT 1 (PT) 00046. EUROSPORT 2 (PT) 00047. FOX (PT) 00048. FOX COMEDY (PT) 00049. FOX CRIME (PT) 00050. FOX MOVIES (PT) 00051. GLOBO PORTUGAL (PT) 00052. GLOBO PREMIUM (PT) 00053. HISTORIA (PT) 00054. HOLLYWOOD (PT) 00055. MCM POP (PT) 00056. NATGEO WILD (PT) 00057. NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC HD (PT) 00058. NICKJR (PT) 00059. ODISSEIA (PT) 00060. PFC (PT) 00061. PORTO CANAL (PT) 00062. PT-TPAINTERNACIONAL (PT) 00063. RECORD NEWS (PT) 00064.