Shakespeare: the Invention of the Literary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Dublin Gate Theatre Archive, 1928 - 1979

Charles Deering McCormick Library of Special Collections Northwestern University Libraries Dublin Gate Theatre Archive The Dublin Gate Theatre Archive, 1928 - 1979 History: The Dublin Gate Theatre was founded by Hilton Edwards (1903-1982) and Micheál MacLiammóir (1899-1978), two Englishmen who had met touring in Ireland with Anew McMaster's acting company. Edwards was a singer and established Shakespearian actor, and MacLiammóir, actually born Alfred Michael Willmore, had been a noted child actor, then a graphic artist, student of Gaelic, and enthusiast of Celtic culture. Taking their company’s name from Peter Godfrey’s Gate Theatre Studio in London, the young actors' goal was to produce and re-interpret world drama in Dublin, classic and contemporary, providing a new kind of theatre in addition to the established Abbey and its purely Irish plays. Beginning in 1928 in the Peacock Theatre for two seasons, and then in the theatre of the eighteenth century Rotunda Buildings, the two founders, with Edwards as actor, producer and lighting expert, and MacLiammóir as star, costume and scenery designer, along with their supporting board of directors, gave Dublin, and other cities when touring, a long and eclectic list of plays. The Dublin Gate Theatre produced, with their imaginative and innovative style, over 400 different works from Sophocles, Shakespeare, Congreve, Chekhov, Ibsen, O’Neill, Wilde, Shaw, Yeats and many others. They also introduced plays from younger Irish playwrights such as Denis Johnston, Mary Manning, Maura Laverty, Brian Friel, Fr. Desmond Forristal and Micheál MacLiammóir himself. Until his death early in 1978, the year of the Gate’s 50th Anniversary, MacLiammóir wrote, as well as acted and designed for the Gate, plays, revues and three one-man shows, and translated and adapted those of other authors. -

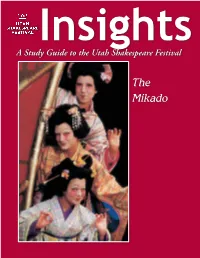

The Mikado the Articles in This Study Guide Are Not Meant to Mirror Or Interpret Any Productions at the Utah Shakespeare Festival

Insights A Study Guide to the Utah Shakespeare Festival The Mikado The articles in this study guide are not meant to mirror or interpret any productions at the Utah Shakespeare Festival. They are meant, instead, to be an educational jumping-off point to understanding and enjoying the plays (in any production at any theatre) a bit more thoroughly. Therefore the stories of the plays and the interpretative articles (and even characters, at times) may differ dramatically from what is ultimately produced on the Festival’s stages. Insights is published by the Utah Shakespeare Festival, 351 West Center Street; Cedar City, UT 84720. Bruce C. Lee, communications director and editor; Phil Hermansen, art director. Copyright © 2011, Utah Shakespeare Festival. Please feel free to download and print Insights, as long as you do not remove any identifying mark of the Utah Shakespeare Festival. For more information about Festival education programs: Utah Shakespeare Festival 351 West Center Street Cedar City, Utah 84720 435-586-7880 www.bard.org. Cover photo: Erin Annarella (top), Carol Johnson, and Sarah Dammann in The Mikado, 1996 Contents Information on the Play Synopsis 4 CharactersThe Mikado 5 About the Playwright 6 Scholarly Articles on the Play Mere Pish-Posh 8 Utah Shakespeare Festival 3 351 West Center Street • Cedar City, Utah 84720 • 435-586-7880 Synopsis: The Mikado Nanki-Poo, the son of the royal mikado, arrives in Titipu disguised as a peasant and looking for Yum- Yum. Without telling the truth about who he is, Nanki-Poo explains that several months earlier he had fallen in love with Yum-Yum; however she was already betrothed to Ko-Ko, a cheap tailor, and he saw that his suit was hopeless. -

Sant Och Falskt I Filmen Shakespeare in Love

Sant och falskt i filmen Shakespeare in Love SHAKESPEARE IN LOVE (1998, regi filmskaparna oroliga att publiken John Madden) är en härlig film som skulle bli förvirrade över att en teater tål att ses många gånger. Upplevelsen hette the Theatre. av den förhöjs om man känner till vad i den som stämmer med den MÅNGA AV ROLLFIGURERNA har historiska verkligheten, vad som är historiska förebilder. Sir Edmund fel och vad som är skämt. Här är ett Tilney (spelad av Simon Callow) var blygsamt försök att reda ut vad som Master of the Revels och ansvarig är vad: både för underhållning vid hovet och Den stora felaktigheten är att för teatercensuren. Philip Henslowe William Shakespeare (Joseph (Geoffrey Rush) ägde Rose-teatern. Fiennes) i filmens början har skriv- Edward – Ned – Alleyn (Ben Aff- kramp. Han har redan erhållit för- leck) var den stora stjärnan där, skott för en pjäs (Sådant förekom) medan Richard Burbage (Martin men har bara fått till titeln Romeo and Clunes) var den ledande aktören på Ethel, piratens dotter. Skrivkrampen Theatre. I rollistan finns också beror på kärleksbrist och löses när namnen på några av tidens William får ihop det med den skådespelare: Henry Condell, John teaterintresserade unga överklass- Rose-teatern där mycket av hand- Hemmings, Will Kempe. kvinnan Viola (Gwyneth Paltrow). lingen utspelas är en relativt trogen Christopher Marlowe (Rupert Kärlekshistorien påverkar pjäsen, som rekonstruktion av den teater som Everett) var den största dramatikern i utvecklas till Romeo och Juliet. fanns i Southwark, söder om England före Shakespeare. Han blev I verkligheten bygger Romeo och Themsen. Originalet var dock mycket riktigt dödad i ett knivslags- Juliet på en episk dikt av Arthur troligen mer färgstarkt och praktfullt mål 1593. -

PAPERS of SÉAMUS DE BÚRCA (James Bourke)

Leabharlann Náisiúnta na hÉireann National Library of Ireland Collection List No. 74 PAPERS OF SÉAMUS DE BÚRCA (James Bourke) (MSS 34,396-34,398, 39,122-39,201, 39,203-39,222) (Accession Nos. 4778 and 5862) Papers of the playwright Séamus De Búrca and records of the firm of theatrical costumiers P.J. Bourke Compiled by Peter Kenny, Assistant Keeper, 2003-2004 Contents INTRODUCTION 12 The Papers 12 Séamus De Búrca (1912-2002) 12 Bibliography 12 I Papers of Séamus De Búrca 13 I.i Plays by De Búrca 13 I.i.1 Alfred the Great 13 I.i.2 The Boys and Girls are Gone 13 I.i.3 Discoveries (Revue) 13 I.i.4 The Garden of Eden 13 I.i.5 The End of Mrs. Oblong 13 I.i.6 Family Album 14 I.i.7 Find the Island 14 I.i.8 The Garden of Eden 14 I.i.9 Handy Andy 14 I.i.10 The Intruders 14 I.i.11 Kathleen Mavourneen 15 I.i.12 Kevin Barry 15 I.i.13 Knocknagow 15 I.i.14 Limpid River 15 I.i.15 Making Millions 16 I.i.16 The March of Freedom 16 I.i.17 Mrs. Howard’s Husband 16 I.i.18 New Houses 16 I.i.19 New York Sojourn 16 I.i.20 A Tale of Two Cities 17 I.i.21 Thomas Davis 17 I.i.22 Through the Keyhole 17 I.i.23 [Various] 17 I.i.24 [Untitled] 17 I.i.25 [Juvenalia] 17 I.ii Miscellaneous notebooks 17 I.iii Papers relating to Brendan and Dominic Behan 18 I.iv Papers relating to Peadar Kearney 19 I.v Papers relating to Queen’s Theatre, Dublin 22 I.vi Essays, articles, stories, etc. -

Style in the Music of Arthur Sullivan: an Investigation

Open Research Online The Open University’s repository of research publications and other research outputs Style in the Music of Arthur Sullivan: An Investigation Thesis How to cite: Strachan, Martyn Paul Lambert (2018). Style in the Music of Arthur Sullivan: An Investigation. PhD thesis The Open University. For guidance on citations see FAQs. c 2017 The Author https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Version: Version of Record Link(s) to article on publisher’s website: http://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21954/ou.ro.0000e13e Copyright and Moral Rights for the articles on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. For more information on Open Research Online’s data policy on reuse of materials please consult the policies page. oro.open.ac.uk STYLE IN THE MUSIC OF ARTHUR SULLIVAN: AN INVESTIGATION BY Martyn Paul Lambert Strachan MA (Music, St Andrews University, 1983) ALCM (Piano, 1979) Submitted 30th September 2017 for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences Open University 1 Abstract ABSTRACT Style in the Music of Arthur Sullivan: An Investigation Martyn Strachan This thesis examines Sullivan’s output of music in all genres and assesses the place of musical style within them. Of interest is the case of the comic operas where the composer uses parody and allusion to create a persuasive counterpart to the libretto. The thesis attempts to place Sullivan in the context of his time, the conditions under which he worked and to give due weight to the fact that economic necessity often required him to meet the demands of the market. -

Keys Fine Art Auctioneers 8 Market Place Aylsham Norwich Two Day Sale of Books, Ephemera & Maps Norfolk NR11 6EH Started 30 Jan 2014 10:00 GMT United Kingdom

Keys Fine Art Auctioneers 8 Market Place Aylsham Norwich Two Day Sale of Books, Ephemera & Maps Norfolk NR11 6EH Started 30 Jan 2014 10:00 GMT United Kingdom Lot Description 1 CONSTANCE AND W NOEL IRVING: A CHILD’S BOOK OF HOURS, L, Humphrey Milford, [1921], 1st edn, fo, orig cl bkd pict bds, d/w ROBERT SCHUMANN: SCHUMANN ALBUM OF CHILDREN’S PIECES FOR PIANO, ill H Willebeek le Mair, L [1913], 1st edn, 4to, orig 2 cl bkd bds, pict paper label + ALAN ALEXANDER MILNE: A GALLERY OF CHILDREN, ill H Willebeek le Mair, 1925, 7th edn, 4to, orig cl, pict paper label (2) 3 LOUIS WAIN: TATTERS THE PUPPY, [1919], 1st edn, shaped book, orig pict wraps D J WATKINS-PITCHFORD ”BB”: MR BUMSTEAD, 1958, 1st edn, org cl, d/w + A WINDSOR-RICHARDS: THE VIX THE STORY OF A 4 FOX CUB, Ill D J Watkins-Pitchford, 1960, 1st edn, orig cl, d/w, (2) 5 D J WATKINS-PITCHFORD “BB”: AT THE BACK O’ BEN DEE, 1968, 1st edn, orig cl, d/w ALAN ALEXANDER MILNE (2 ttls): NOW WE ARE SIX, Ill E H Shepard, 1927, 1st edn, orig cl, gt; THE CHRISTOPHER ROBIN 6 STORYBOOK, Ill E H Shepard, 1929, 1st edn, orig cl, gt, d/w (tatty), (2) 7 CLIVE STAPLES LEWIS: THE LION, THE WITCH AND THE WARDROBE, Ill Pauline Baynes, 1950, 1st edn, orig cl CLIVE STAPLES LEWIS (2 ttls): THE SILVER CHAIR, Ill Pauline Baynes, 1953, 1st edn, orig cl; THE LAST BATTLE, Ill Pauline 8 Baynes, 1956, 1st edn, orig cl, (2) CLIVE STAPES LEWIS (2 ttls): THE MAGICIAN’S NEPHEW, Ill Pauline Baynes, 1955, 1st edn, orig cl; THE LAST BATTLE, Ill Pauline 9 Baynes, 1958, 2nd impress, orig cl, d/w, (2) MARY NORTON: THE BORROWERS, -

Who Was William Shakespeare?*

On Biography ISSN 2283-8759 DOI 10.13133/2283-8759-2 pp. 61-79 (December 2015) Who Was William Shakespeare?* Graham Holderness What a strange question! Shakespeare is acknowledged throughout the world as one of the greatest, if not the greatest, of writers; he has an unrivalled position as the greatest author of British culture. Can you imagine anyone asking that question of any other national writer? Who was Miguel de Cervantes? Who was Dante Alighieri? Who was Johannes Wolfgang von Goethe? So why Shakespeare? The problem is everywhere. It troubles even Gwyneth Paltrow. “Are you the author of the plays of William Shakespeare?” asks Viola de Lessops, in the film Shakespeare in Love. What a roundabout way of asking someone’s name! “Are you William Shakespeare?” would have been simpler. But Viola is, in fact, not just after a man, but in quest of a literary biography. She knew and loved the plays, before she knew and loved the author. Like her original, Viola Compton in the comic novel No Bed for Bacon1, she doesn’t want just any man, even one as dashing and soulful and sexy as Joseph Fiennes. She wants the author of the plays of William Shakespeare; who happens, in this instance, to be William Shakespeare himself. And fortunately for her, Shakespeare is, in the film, dashing and soulful and sexy, and not, for example, as he might have been in life, little, balding, grumpy and gay. And that involved syntax even sneaks in the pos- sibility that “the author of the plays of William Shakespeare” might * A number of passages in this article previously appeared in Graham Holderness, Nine Lives of William Shakespeare, The Arden Shakespeare, London, Bloomsbury Publishing, 2011. -

Little Master Shakespeare Free

FREE LITTLE MASTER SHAKESPEARE PDF Jennifer Adams | 22 pages | 10 Oct 2011 | Gibbs M. Smith Inc | 9781423622055 | English | Layton, United States Shakespeare's Boss: The Master of Revels Shakespeare in Love is a romantic period comedy-drama film directed by John Maddenwritten by Marc Norman and playwright Tom Stoppardand produced by Harvey Weinstein. Little Master Shakespeare characters are based on historical figures, and many of the characters, lines, and plot devices allude to Shakespeare's plays. Suffering from writer's block with a new comedy, Romeo and Little Master Shakespeare, the Pirate's DaughterShakespeare attempts to seduce Rosaline, mistress of Richard Burbageowner of the rival Curtain Theatreand to convince Burbage to buy the play from Henslowe. Shakespeare receives advice from rival playwright Christopher Marlowebut is despondent to learn Rosaline is sleeping with Master of the Revels Edmund Tilney. The desperate Henslowe, in debt to ruthless moneylender Fennyman, begins auditions anyway. Viola de Lesseps, daughter of a wealthy Little Master Shakespeare, who has seen Shakespeare's plays at court, disguises herself as a man named Thomas Kent to audition. He pursues Kent to Viola's house and leaves a note with her nurse, asking Kent to begin rehearsals at the Rose. Shakespeare sneaks into a ball at the house, where Viola's parents arrange her betrothal to impoverished aristocrat Lord Wessex. Dancing with Viola, Shakespeare is struck speechless and ejected by Wessex, who threatens to kill him, leading Shakespeare to say that he is Christopher Marlowe. He finds Viola on her balcony, where they confess their mutual attraction before he is discovered by her nurse and flees. -

Open Research Online Oro.Open.Ac.Uk

Open Research Online The Open University’s repository of research publications and other research outputs Style in the Music of Arthur Sullivan: An Investigation Thesis How to cite: Strachan, Martyn Paul Lambert (2018). Style in the Music of Arthur Sullivan: An Investigation. PhD thesis The Open University. For guidance on citations see FAQs. c 2017 The Author Version: Version of Record Copyright and Moral Rights for the articles on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. For more information on Open Research Online’s data policy on reuse of materials please consult the policies page. oro.open.ac.uk STYLE IN THE MUSIC OF ARTHUR SULLIVAN: AN INVESTIGATION BY Martyn Paul Lambert Strachan MA (Music, St Andrews University, 1983) ALCM (Piano, 1979) Submitted 30th September 2017 for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences Open University 1 Abstract ABSTRACT Style in the Music of Arthur Sullivan: An Investigation Martyn Strachan This thesis examines Sullivan’s output of music in all genres and assesses the place of musical style within them. Of interest is the case of the comic operas where the composer uses parody and allusion to create a persuasive counterpart to the libretto. The thesis attempts to place Sullivan in the context of his time, the conditions under which he worked and to give due weight to the fact that economic necessity often required him to meet the demands of the market. The influence of his early training is examined as well as the impact of the early Romantic German school of composers such as Mendelssohn, Schubert and Schumann. -

Bonded Shakespeare

Iulian Boldea, Cornel Sigmirean (Editors) MULTICULTURAL REPRESENTATIONS. Literature and Discourse as Forms of Dialogue Arhipelag XXI Press, Tîrgu Mureș, 2016 69 ISBN: 978-606-8624-16-7 Section: Literature BONDED SHAKESPEARE Dragoș Avădanei Assoc. Prof., PhD, ”Al. Ioan Cuza” University of Iași Abstract:To study Shakespeare’s following as a literary influence in the world is next to impossible, due to the immense number of writings, in countless languages, published in the past four-hundred years. As the title suggests, this paper refers to an intriguing twentieth-century British playwright, Edward Bond, who proposes two Shakespeare-related plays, Lear (1971) and Bingo (1973), where the great Renaissance bard is not only radically transformed, but also drastically diminished: King Lear is re-written in Lear as a systematic and hostile critique of Shakespeare’s masterpiece, full of violence, cruelty, aggressiveness…, and “extravagance that is both boring and repellent”; Bingo, in its turn, proposes a revisionist portrait of Shakespeare as a man (in his final days) and an author, a denunciation of the great dramatist by an ideologically motivated Marxist-socialist-Brechtian writer. Keywords: Shakespeare, Bond, Lear, re-write, Marxism, Brecht In the past four hundred years “William Shakespeare” has become the greatest literary-cultural phenomenon of all times: his work has been translated into practically all the languages of the globe /sic!/; his plays have not only been staged in numberless theaters, but were also re-written, adapted, imitated, -

Gender Inequality in John Madden's Shakespeare in Love

0 GENDER INEQUALITY IN JOHN MADDEN’S SHAKESPEARE IN LOVE: FEMINIST APPROACH Research Paper Submitted as a Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for Getting Bachelor Degree in English Department By Woro Widowati A 320 050 355 SCHOOL OF TEACHING TRAINING AND EDUCATION MUHAMMADIYAH UNIVERSITY OF SURAKARTA 2009 1 CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION A. Background of the Study Shakespeare in Love is a movie directed by John Madden. He is a famous director in U.S. He also has created many movies like Captain Corelli's Mandolin before. He has gotten several Academic Awards as the best director because of his great movies. Shakespeare in Love firstly is written by Marc Norman. He proposes great story and plot which more concerns the Shakespeare’s life. There are also several producers who cooperate for finishing this movie. They are Marshall Herskovitz, Marc Norman, David Parfitt, Harvey Weinstein, Edward Zwick. This movie firstly was released on 12 December 1998 in U.S and was distributed by Universal Picture, Miramax film in U.S. United State is one of the big country which has created a million great movies. One of them is entitled “Shakespeare in Love”. It shows Shakespeare’s love with Viola acted by Gwyneth Paltrow. The setting of time is around 1593 or sixteenth century in London. The duration of its movie is about 2:03 or 123 minutes. During this time, the viewers are able to understand the story of Shakespeare’s love. Shakespeare in Love also performs great actors like Joseph Fiennes (William Shakespeare), Gwyneth Paltrow (Viola), Geoffrey Rush (Philiph Henslowe), Colin Firth (Lord Wessex), Ben Affleck (Ned Alleyn), Tom Wilkinson (Fennyman), Imelda (nurse). -

Restaging the Ballets of Antony Tudor A

PRESERVING A LEGACY, PRESERVING BALLET HISTORY: RESTAGING THE BALLETS OF ANTONY TUDOR A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE TEXAS WOMAN’S UNIVERSITY DEPARTMENT OF DANCE COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES BY CHRISTINE KNOBLAUCH-O’NEAL A.B., M.A.L.S. DENTON, TEXAS MAY 2013 [Type a quotei from the document or the summary of an interesting point. You can position the text box anywhere in the Copyright © Christine Knoblauch-O’Neal, 2013 all rights reserved iii DEDICATION To Grant and Kathleen Knoblauch, they were the best parents. iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to gratefully acknowledge the many individuals who have contributed to this dissertation. I would like to thank my committee chair Dr. Linda Caldwell for her continued interest in this research. I want to thank Sally Bliss executor of the Tudor will and Trustee of the Antony Tudor Ballet Trust for allowing me full access to the Trust and to the Répétiteurs of the Trust who participated in my research. The research could not have been completed without her continued interest and support of this project. I am grateful to both Dr. Janet Brown and Betty Skinner for their continued encouragement and guidance during my beginning efforts to create a document worthy of the topic. In particular, I want to thank my sister Karen Brewington for her continued support and encouragement throughout my doctoral studies. All scholars should be fortunate enough to have sisters like Karen. And, finally, I want to thank Mike Lang for being there for me during every moment of my doctoral studies, listening to me, challenging me, and encouraging me to feel confident in my work.