Hans Arp and the United States

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

32026062-MIT.Pdf

K.'-.- A, N E W Q UA D R A N G L E F O R C O R N E L L U N I V E R S I T Y A Thesis.submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement s for the degree of Master of Architec ture at the Massachusetts Inst itute of Technology August 15, 1957 Dean Pie tro Bel lus ch Dean of the School of Archi tecture and P lanning Professor000..eO0 Lawrence*e. *90; * 9B. Anderson Head oythe Departmen ty6 Arc,hi tecture Earl Robert"'F a's burgh Bachelor of Architecture, Cornell University,9 June 1954 323 Westgate West Cambridge 39, Mass. August 14, 1957 Dean Pietro Belluschi School of Architecture and Planning Massachusetts Institute of Technology Cambridge 39, Massachusetts Dear De-an Belluschi, In partial fulfillment- of the requirements for the degree of Master of Architecture, I should like to submitimy thesis entitled, "A New Quad- rangle for Cornell University". Sincer y yours, -"!> / /Z /-7xIe~ Earl Robert Fla'nsburgh gr11 D E D I C A T I O N To my wife, Polly A C K N O W L E D G E M E N T S The development of this thesis has been aided by many members of the s taff at both M.I.T. &nd Cornell University. W ithou t their able guidance and generous assistance this t hesis would not have been possible. I would li ke to take this opportunity to acknowledge the help of the following: At M. I. T. -

Hans Ulrich Obrist a Brief History of Curating

Hans Ulrich Obrist A Brief History of Curating JRP | RINGIER & LES PRESSES DU REEL 2 To the memory of Anne d’Harnoncourt, Walter Hopps, Pontus Hultén, Jean Leering, Franz Meyer, and Harald Szeemann 3 Christophe Cherix When Hans Ulrich Obrist asked the former director of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, Anne d’Harnoncourt, what advice she would give to a young curator entering the world of today’s more popular but less experimental museums, in her response she recalled with admiration Gilbert & George’s famous ode to art: “I think my advice would probably not change very much; it is to look and look and look, and then to look again, because nothing replaces looking … I am not being in Duchamp’s words ‘only retinal,’ I don’t mean that. I mean to be with art—I always thought that was a wonderful phrase of Gilbert & George’s, ‘to be with art is all we ask.’” How can one be fully with art? In other words, can art be experienced directly in a society that has produced so much discourse and built so many structures to guide the spectator? Gilbert & George’s answer is to consider art as a deity: “Oh Art where did you come from, who mothered such a strange being. For what kind of people are you: are you for the feeble-of-mind, are you for the poor-at-heart, art for those with no soul. Are you a branch of nature’s fantastic network or are you an invention of some ambitious man? Do you come from a long line of arts? For every artist is born in the usual way and we have never seen a young artist. -

Max Ernst Was a German-Born Surrealist Who Helped Shape the Emergence of Abstract Expressionism in America Post-World War II

QUICK VIEW: Synopsis Max Ernst was a German-born Surrealist who helped shape the emergence of Abstract Expressionism in America post-World War II. Armed with an academic understanding of Freud, Ernst often turned to his work-whether sculpture, painting, or collage-as a means of processing his experience in World War I and unpacking his feelings of dispossession in its wake. Key Ideas / Information • Ernst's work relied on spontaneity (juxtapositions of materials and imagery) and subjectivity (inspired by his personal experiences), two creative ideals that came to define Abstract Expressionism. • Although Ernst's works are predominantly figurative, his unique artistic techniques inject a measure of abstractness into the texture of his work. • The work of Max Ernst was very important in the nascent Abstract Expressionist movement in New York, particularly for Jackson Pollock. DETAILED VIEW: Childhood © The Art Story Foundation – All rights Reserved For more movements, artists and ideas on Modern Art visit www.TheArtStory.org Max Ernst was born into a middle-class family of nine children on April 2, 1891 in Brühl, Germany, near Cologne. Ernst first learned painting from his father, a teacher with an avid interest in academic painting. Other than this introduction to amateur painting at home, Ernst never received any formal training in the arts and forged his own artistic techniques in a self-taught manner instead. After completing his studies in philosophy and psychology at the University of Bonn in 1914, Ernst spent four years in the German army, serving on both the Western and Eastern fronts. Early Training The horrors of World War I had a profound and lasting impact on both the subject matter and visual texture of the burgeoning artist, who mined his personal experiences to depict absurd and apocalyptic scenes. -

Paintings by John W. Alexander ; Sculpture by Chester Beach

SPECIAL EXHIBITIONS THE ART INSTITUTE OF CHICAGO, DECEMBER 12 1916 TO JANUARY 2, 1917 PAINTINGS BY JOHN W. ALEXANDER SCULPTURE BY CHESTER BEACH PAINTINGS BY CALIFORNIA ARTISTS PAINTINGS BY WILSON IRVINE PAINTINGS BY EDWARD W. REDFIELD PAINTINGS, DRAWINGS AND SKETCHES BY MAURICE STERNE 0 SPECIAL EXHIBITIONS OF WORK BY THE FOLLOWING ARTISTS PAINTINGS BY JOHN W. ALEXANDER SCULPTURE BY CHESTER BEACH PAINTINGS BY CALIFORNIA ARTISTS PAINTINGS BY WILSON IRVINE PAINTINGS BY EDWARD W. REDFIELD PAINTINGS, DRAWINGS AND SKETCHES BY MAURICE STERNE THE ART INSTITUTE OF CHICAGO DEC. 12, 1916 TO JAN. 2, 1917 PAINTINGS BY JOHN WHITE ALEXANDER OHN vV. ALEXANDER. Born, Pittsburgh, J Pennsylvania, 1856. Died, New York, May 31, 1915. Studied at the Royal Academy, Munich, and with Frank Duveneck. Societaire of Societe Nationale des Beaux Arts, Paris; Member of the International Society of Sculptors, Painters and Gravers, London; Societe Nouvelle, Paris ; Societaire of the Royal Society of Fine Arts, Brussels; President of the National Academy of Design, New York; President of the Natiomrl Academy Association; President of the National Society of Mural Painters, New York; Ex- President of the National Institute of Arts and Letters, New York; American Academy of Arts and Letters; Vice-President of the National Fine Arts Federation, Washington, D. C.; Member of the Architectural League, Fine Arts Federation and Fine Arts Society, New York; Honorary Member of the Secession Society, Munich, and of the Secession Society, Vienna; Hon- orary Member of the Royal Society of British Artists, of the American Institute of Architects and of the New York Society of Illustrators; President of the School Art League, New York; Trustee of the New York Public Library; Ex-President of the MacDowell Club, New York; Trustee of the Metropolitan Museum of Art; Trustee of the American Academy in Rome; Chevalier of the Legion of Honor, France; Honorary Degree of Master of Arts, Princeton University, 1892, and of Doctor of Literature, Princeton, 1909. -

Art on the Page

Art on the page Toward a modern illustrated book When Parisian art dealer Ambroise Vollard issued his first publication, Parallèlement, in 1900, a collection of poems by Paul Verlaine illustrated with lithographs by Impressionist painter Pierre Bonnard, he ushered in a new form of illustrated book to mark the new century. In the following decades, he and other entrepreneurial art publishers such as Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler and Albert Skira would take advantage of a widening pool of book collectors interested in modern art by producing deluxe books that featured original prints by artists such as Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse, Georges Rouault, André Derain and others. These books are generally referred to as livres des artistes and, unlike the fine press publications produced by the Kelmscott Press, the Doves Press or Ashendene Press, the earliest examples were distinguished by their modernity. Breon Mitchell, in his introduction to Beyond illustration, argues that the livre d’artiste can be differentiated from the traditional book in several respects: The illustrations are, in each case, original works of art (woodcuts, lithographs, etchings, engravings) executed by the artist himself and printed under his supervision. The book thus contains original graphics of the kind which find their place on museum walls … The livre d’artiste is also defined by the stature of the artist. Virtually every major painter and sculptor of the twentieth century—Picasso, Braque, Ernst, Matisse, Kokoschka, Barlach, Miró, to name a few—has collaborated in the creation of one or more such works. In many cases, book illustration has occupied such an important place in the total oeuvre of the artist that no student of art history can safely ignore it. -

Drawing Surrealism Didactics 10.22.12.Pdf

^ Drawing Surrealism Didactics Drawing Surrealism is the first-ever large-scale exhibition to explore the significance of drawing and works on paper to surrealist innovation. Although launched initially as a literary movement with the publication of André Breton’s Manifesto of Surrealism in 1924, surrealism quickly became a cultural phenomenon in which the visual arts were central to envisioning the world of dreams and the unconscious. Automatic drawings, exquisite corpses, frottage, decalcomania, and collage are just a few of the drawing-based processes invented or reinvented by surrealists as means to tap into the subconscious realm. With surrealism, drawing, long recognized as the medium of exploration and innovation for its use in studies and preparatory sketches, was set free from its associations with other media (painting notably) and valued for its intrinsic qualities of immediacy and spontaneity. This exhibition reveals how drawing, often considered a minor medium, became a predominant mode of expression and innovation that has had long-standing repercussions in the history of art. The inclusion of drawing-based projects by contemporary artists Alexandra Grant, Mark Licari, and Stas Orlovski, conceived specifically for Drawing Surrealism , aspires to elucidate the diverse and enduring vestiges of surrealist drawing. Drawing Surrealism is also the first exhibition to examine the impact of surrealist drawing on a global scale . In addition to works from well-known surrealist artists based in France (André Masson, Max Ernst, Joan Miró, Salvador Dalí, among them), drawings by lesser-known artists from Western Europe, as well as from countries in Eastern Europe and the Americas, Great Britain, and Japan, are included. -

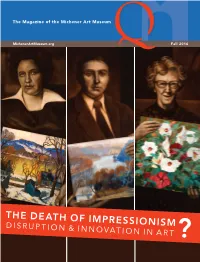

The Death of Impressionism

The Magazine of the Michener Art Museum MichenerArtMuseum.org Fall 2016 | THE DEATH OF IMPRESSIONISM DISRUPTION & INNOVATION IN ART Q-Fall2016.indd 1 8/18/16 3:58 PM EXHIBITIONS/ PROGRAMS Death of Impressionism? DIREctor’SSPOTLIGHT Disruption & Innovation in Art 3-6 Our summer was an extraordinary one, with filled- FALL 2016 FALL Shifting the Limits: Robert Engman’s Structural Sculpture 7 to-capacity summer art camps, music programs, and exhibitions that touched local and international Jonathan Hertzel: When Sparks Fly 8 communities with their rich imagery and powerful Highlights from the New Hope statements. Solebury School District Art We celebrated the expansion of the Panama Canal Collection 8 with Oh Panama! Jonas Lie Paints the Panama Canal, Unguarded, Untold, Iconic: explored local color with New Hope artist Lloyd Afghanistan through the Ney, featured artists new to the Michener in Tête-à- Lens of Steve McCurry 9 Tête: Conversations in Photography, and explored Lloyd Ney: Local Color 10 | the exotic and poignant world of Afghanistan with 2 Tête-a-Tête: Conversations in Unguarded, Untold, Iconic: Afghanistan through the Photography 10 Lens of Steve McCurry. Afghanistan Ambassador Oh Panama!: Jonas Lie Paints the Panama Canal 10 Hamdullah Mohib was due to attend our opening reception for Steve McCurry in July but standstill highway traffic made it impossible. He was able to call in via speaker Coming Soon 11-12 phone, however, to share his congratulations and perspectives, observing that Collections 13 McCurry’s photographs capture both the beauty and realities of Afghanistan, and Public Programs 14-15 expressing appreciation for the friendship between his country and the United States. -

Milch Galleries

THE MILCH GALLERIES YORK THE MILCH GALLERIES IMPORTANT WORKS IN PAINTINGS AND SCULPTURE BY LEADING AMERICAN ARTISTS 108 WEST 57TH STREET NEW YORK CITY Edition limited to One Thousand copies This copy is No 1 his Booklet is the second of a series we have published which deal only with a selected few of the many prominent American artists whose work is always on view in our Galleries. MILCH BUILDING I08 WEST 57TH STREET FOREWORD This little booklet, similar in character to the one we pub lished last year, deals with another group of painters and sculp tors, the excellence of whose work has placed them m the front rank of contemporary American art. They represent differen tendencies, every one of them accentuating some particular point of view and trying to find a personal expression for personal emotions. Emile Zola's definition of art as "nature seen through a temperament" may not be a complete and final answer to the age-old question "What is art?»-still it is one of the best definitions so far advanced. After all, the enchantment of art is, to a large extent, synonymous with the magnetism and charm of personality, and those who adorn their homes with paintings, etchings and sculptures of quality do more than beautify heir dwelling places. They surround themselves with manifestation of creative minds, with clarified and visualized emotions that tend to lift human life to a higher plane. _ Development of love for the beautiful enriches the resources of happiness of the individual. And the welfare of nations is built on no stronger foundation than on the happiness of its individual members. -

Alexander Calder James Johnson Sweeney

Alexander Calder James Johnson Sweeney Author Sweeney, James Johnson, 1900-1986 Date 1943 Publisher The Museum of Modern Art Exhibition URL www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/2870 The Museum of Modern Art's exhibition history— from our founding in 1929 to the present—is available online. It includes exhibition catalogues, primary documents, installation views, and an index of participating artists. MoMA © 2017 The Museum of Modern Art THE MUSEUM OF RN ART, NEW YORK LIBRARY! THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART Received: 11/2- JAMES JOHNSON SWEENEY ALEXANDER CALDER THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART, NEW YORK t/o ^ 2^-2 f \ ) TRUSTEESOF THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART Stephen C. Clark, Chairman of the Board; McAlpin*, William S. Paley, Mrs. John Park Mrs. John D. Rockefeller, Jr., ist Vice-Chair inson, Jr., Mrs. Charles S. Payson, Beardsley man; Samuel A. Lewisohn, 2nd Vice-Chair Ruml, Carleton Sprague Smith, James Thrall man; John Hay Whitney*, President; John E. Soby, Edward M. M. Warburg*. Abbott, Vice-President; Alfred H. Barr, Jr., Vice-President; Mrs. David M. Levy, Treas HONORARY TRUSTEES urer; Mrs. Robert Woods Bliss, Mrs. W. Mur ray Crane, Marshall Field, Philip L. Goodwin, Frederic Clay Bartlett, Frank Crowninshield, A. Conger Goodyear, Mrs. Simon Guggenheim, Duncan Phillips, Paul J. Sachs, Mrs. John S. Henry R. Luce, Archibald MacLeish, David H. Sheppard. * On duty with the Armed Forces. Copyright 1943 by The Museum of Modern Art, 11 West 53 Street, New York Printed in the United States of America 4 CONTENTS LENDERS TO THE EXHIBITION Black Dots, 1941 Photo Herbert Matter Frontispiece Mrs. Whitney Allen, Rochester, New York; Collection Mrs. -

1969 Compassion and Care

Justice Holmes • Inflammation • Harry Widener MAY-JUNE 2019 • $4.95 Compassion 1969 and Care Physician-Poet Rafael Campo Reprinted from Harvard Magazine. For more information, contact Harvard Magazine, Inc. at 617-495-5746 May 2019 Dear Reader, In 1898, an association of Harvard graduates established the Harvard Alumni Bulletin, “to give selected and summarized Harvard news to graduates who want it” and “to serve as a medium for publishing promptly all notices and announcements of interest to graduates.” members and students extend the limits of discovery and human understanding—in service to an ever more far- ung, diverse group of alumni around the globe. Today, nearly a century and a quarter later, the name has changed, to Harvard Magazine (as have the look and contents), but the founding Your Harvard Magazine can capture alumni voices (see the letters responding to the March-April principles have not: feature on the events of April 1969, beginning on page 4 of this issue), dive deep into critical research (read the feature on the scientists exploring in ammation, and how their work contributes • e magazine exists to serve the interests of its readers (now including all University to understanding disease, on page 46), and keep you current on the critical issues facing higher alumni, faculty, and sta )—not any other agenda. education on campus and around the world (see John Harvard’s Journal, beginning on page 18). • Readers’ support is the most important underpinning of this commitment to high- Your contribution underwrites the journalism you are reading now, the expanded coverage quality, editorially independent journalism on readers’ behalf. -

The Nature Ofarp Live Text-78-87.Indd 78

modern painters modernpaintersAPRIL 2019 PHILIPP THE COLORS OF ZEN: A CONVERSATION WITH HSIAO CHIN FÜRHOFER EXPLAINS HIS INSPIRATION TOP 10 ART BOOKS KIM CHONG HAK: THE KOREAN VAN GOGH BLOUINARTINFO.COM APRIL APRIL BLOUINARTINFO.COM + TOP 10: CONTEMPORARY POETS TO READ IN 2019 2019 04_MP_COVER.indd 1 19/03/19 3:56 PM 04_MP_The nature ofArp_Live text-78-87.indd 78 © 2019 ARTISTS RIGHTS SOCIETY (ARS), NEW YORK/VG BILD-KUNST, BONN / © JEAN ARP, BY SIAE 2019. PHOTO: KATHERINE DU TIEL/SFMOMA 19/03/19 4:59PM Jean (Hans) Arp, “Objects Arranged according to the Laws of Chance III,” 1931, oil on wood, 10 1/8 x 11 3/8 x 2 3/8 in., San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. THE NATURE OF ARP THE SCULPTOR REFUSED TO BE CATEGORIZED, AS AN ARTIST OR AS A HUMAN BEING, MAKING A RETROSPECTIVE AT THE GUGGENHEIM IN VENICE A PECULIAR CHALLENGE TO CURATE BY SARAH MOROZ BLOUINARTINFO.COM APRIL 2019 MODERN PAINTERS 79 04_MP_The nature of Arp_Live text-78-87.indd 79 19/03/19 4:59 PM pursue this matter without affiliations with Constructivism and knowing where I’m going,” Surrealism, 1930s-era sinuous sculptures, Jean Arp once said of his collaborative works with Sophie Taeuber- intuitive approach. “This is Arp (his wife, and an artist in her own the mystery: my hands talk right) and the work made from the après- “to themselves.I The dialogue is established guerre period up until his death in 1966. between the plaster and them as if I am Two Project Rooms adjacent to the absent, as if I am not necessary. -

The Sidney and Harriet Janis Collection : a Gift to the Museum of Modern Art

The Sidney and Harriet Janis Collection : a gift to the Museum of Modern Art Author Museum of Modern Art (New York, N.Y.) Date 1968 Publisher The Museum of Modern Art Exhibition URL www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/1886 The Museum of Modern Art's exhibition history— from our founding in 1929 to the present—is available online. It includes exhibition catalogues, primary documents, installation views, and an index of participating artists. MoMA © 2017 The Museum of Modern Art 1 The Sidney and Harriet Janis Collection A Giftto The Museum of Modem Art ) Trustees of The Museum of Modern Art cover: picasso. Painter and Model. 1928 David Rockefeller, Chairman of the Board; Henry Allen Moe, William S. Paley, and John Hay Whitney, Vice Chairmen; Mrs. Bliss Parkinson, President; James Thrall Soby, Ralph F. Colin, and Gardner Cowlcs, Vice Presidents; Willard C. Butcher, Treasurer; Walter Bareiss, Robert R. Barker, Alfred H. Barr, Printed in the United States of America by Clarke & Way, Inc. Jr., Mrs. Robert Woods Bliss*, William A. M. Burden, Ivan Chermayeff, Mrs. W. Murray Crane*, John dc Mcnil, Rene Color plates engraved by Briider Hartmann, West Berlin d'Harnoncourt, Mrs. C. Douglas Dillon, Mrs. Edscl B. Ford, Black-and-white plates by Horan Engraving Company, Inc. Mrs. Simon Guggenheim*, Wallace K. Harrison, Mrs. Walter Hochschild, James W. Hustcd*, Philip Johnson, Mrs. Albert D. Designed by Bert Clarke Lasker, John L. Loeb, Ranald H. Macdonald*, Mrs. G. Mac- culloch Miller*, Mrs. Charles S. Payson, Gifford Phillips, Mrs. © Copyright The Museum of Modern Art, 1968 John D. Rockefeller 3rd, Nelson A.