Upgrading Students' Oral Performance Via the Utilisation of Positive Self-Talk and Personal Goal-Setting. the Case of First Ye

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Edition 2019

YEAR-END EDITION 2019 Global Headquarters Republic Records 1755 Broadway, New York City 10019 © 2019 Mediabase 1 REPUBLIC #1 FOR 6TH STRAIGHT YEAR UMG SCORES TOP 3 -- AS INTERSCOPE, CAPITOL CLAIM #2 AND #3 SPOTS For the sixth consecutive year, REPUBLIC is the #1 label for Mediabase chart share. • The 2019 chart year is based on the time period from November 11, 2018 through November 9, 2019. • All spins are tallied for the full 52 weeks and then converted into percentages for the chart share. • The final chart share includes all applicable label split-credit as submitted to Mediabase during the year. • For artists, if a song had split-credit, each artist featured was given the same percentage for the artist category that was assigned to the label share. REPUBLIC’S total chart share was 19.2% -- up from 16.3% last year. Their Top 40 chart share of 28.0% was a notable gain over the 22.1% they had in 2018. REPUBLIC took the #1 spot at Rhythmic with 20.8%. They were also the leader at Hot AC; where a fourth quarter surge landed them at #1 with 20.0%, that was up from a second place 14.0% finish in 2018. Other highlights for REPUBLIC in 2019: • The label’s total spin counts for the year across all formats came in at 8.38 million, an increase of 20.2% over 2018. • This marks the label’s second highest spin total in its history. • REPUBLIC had several artist accomplishments, scoring three of the top four at Top 40 with Ariana Grande (#1), Post Malone (#2), and the Jonas Brothers (#4). -

Nightmare Magazine, Issue 77 (February 2019)

TABLE OF CONTENTS Issue 77, February 2019 FROM THE EDITOR Editorial: February 2019 FICTION Quiet the Dead Micah Dean Hicks We Are All Monsters Here Kelley Armstrong 58 Rules to Ensure Your Husband Loves You Forever Rafeeat Aliyu The Glottal Stop Nick Mamatas BOOK EXCERPTS Collision: Stories J.S. Breukelaar NONFICTION The H Word: How The Witch and Get Out Helped Usher in the New Wave of Elevated Horror Richard Thomas Roundtable Interview with Women in Horror Lisa Morton AUTHOR SPOTLIGHTS Micah Dean Hicks Rafeeat Aliyu MISCELLANY Coming Attractions Stay Connected Subscriptions and Ebooks Support Us on Patreon or Drip, or How to Become a Dragonrider or Space Wizard About the Nightmare Team Also Edited by John Joseph Adams © 2019 Nightmare Magazine Cover by Grandfailure / Fotolia www.nightmare-magazine.com Editorial: February 2019 John Joseph Adams | 153 words Welcome to issue seventy-seven of Nightmare! We’re opening this month with an original short from Micah Dean Hicks, “Quiet the Dead,” the story of a haunted family in a town whose biggest industry is the pig slaughterhouse. Rafeeat Aliyu’s new short story “58 Rules To Ensure Your Husband Loves You Forever” is full of good relationship advice . if you don’t mind feeding your husband human flesh. We’re also sharing reprints by Kelley Armstrong (“We Are All Monsters Here”) and Nick Mamatas (“The Glottal Stop”). Our nonfiction team has put together their usual array of author spotlights, and in the latest installment of “The H Word,” Richard Thomas talks about exciting new trends in horror films. Since it’s Women in Horror Month, Lisa Morton has put together a terrific panel interview with Linda Addison, Joanna Parypinski, Becky Spratford, and Kaaron Warren—a great group of female writers and scholars. -

Jiwei Ci Vi CONTENTS

CONTEMPORARY CHINESE PHILOSOPHY Edited by CHUNG-YING CHENG AND NICHOLAS BUNNIN CONTEMPORARY CHINESE PHILOSOPHY Dedicated to my mother Mrs Cheng Hsu Wen-shu and the memory of my father Professor Cheng Ti-hsien Chung-ying Cheng Dedicated to my granddaughter Amber Bunnin Nicholas Bunnin CONTEMPORARY CHINESE PHILOSOPHY Edited by CHUNG-YING CHENG AND NICHOLAS BUNNIN Copyright © Blackwell Publishers Ltd 2002 First published 2002 2 4 6 8 10 9 7 5 3 1 Blackwell Publishers Inc. 350 Main Street Malden, Massachusetts 02148 USA Blackwell Publishers Ltd 108 Cowley Road Oxford OX4 1JF UK All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purposes of criticism and review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Except in the United States of America, this book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Contemporary chinese philosophy / edited by Chung-ying Cheng and Nicholas Bunnin p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-631-21724-X (alk. paper) — ISBN 0-631-21725-8 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Philosophy, Chinese—20th century. I. Cheng, Zhongying, 1935– II. -

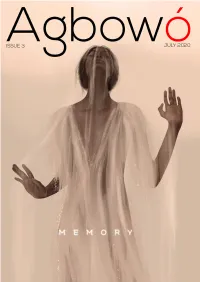

Memory | July 2020 1 Ó

Agbowó | MEMORY | JULY 2020 1 ó Agbowó | MEMORY | JULY 2020 2 About Agbowó Agbowó is growing to be a foremost African art company providing platforms for African writers and artists that ensure creative Africans can concentrate on creating great art while we ensure they get the audience and the value they deserve. Our goal is to create immense value for art lovers whether as creators or as consumers of African art as they might have not experienced before- both through the magnitude of our service and in the way we have chosen to deliver them. Some of our initiatives include Agbowó online literary journal (agbowo.org), the yearly Agbowó magazine (agbowo.org/magazine), the upcoming monthly publication, Monthly (monthly.agbowo.org), our arts events platform, Arts n Chill by Agbowó (ag- bowo.org/artsnchill) and most recently, our platform for publishing third party publica- tions and artworks, Published by Agbowó (published.agbowo.org). We will continue to seek new, innovative and trusted ways to uphold African artistry, craft and creativity. Whether through our own initiatives, partnerships or sponsorships, we will remain true to our purpose of providing global access to cultural and creative Africans and helping them gain value and audience for their work. Agbowó’s registered name is Agbowó Creative African Company, incorporated with the RC number 1575748. Editor’s Note ll we remember of a flood is the running, together, for high ground, holding onto things and to each other for buoyance, and the eventual rope or hand. Memory is not an exclusive preserve of the individual. From time to time, super-sized events engulf us in large swathes soA that there is no space for the nuance of personal experience and its corollary – personal memory. -

THE KNOWING a Fantasy by Kevan Manwaring

APPENDICES Novel (cont.) Kevan Manwaring THE KNOWING A Fantasy by Kevan Manwaring (Continued from Section Two: Creative Component) Submission for a Creative Writing PhD University of Leicester June 2018 Supervisor: Dr Harry Whitehead Student Number: 129044809 ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-1756-5222 www.thesecretcommonwealth.com Page 1 APPENDICES Novel (cont.) Kevan Manwaring REMINDER TO EXAMINERS Motifs are included that relate to supplementary narrative voices, which can be viewed via the website (www.thesecretcommonwealth.com). See ‘Discover the McEttrick Women’ and ‘Discover the Characters’. The novel can be read without referring to these, but it may enhance your experience, if you wish to know more. Additional material is also available on the website: other voices from the world of the novel; audio and video recordings; original artwork; articles (by me as a research- practitioner); photographs of field research; a biographical comic strip about Rev. Robert Kirk; and so on. Collectively, this constitutes the totality of my research project. www.thesecretcommonwealth.com Page 2 APPENDICES Novel (cont.) Kevan Manwaring 22 Janey awoke with a jolt. Turbulence again. Felt like they were riding through a storm. Jim Morrison eat your heart out, she groaned to herself. Being cooped up in a soup can in the sky for hours on end felt like the very opposite of rock'n'roll. All but the safety lights were out. Around her, a small village of strangers slept above the clouds, swaddled in cellophane-static blankets, commode cushions and flight socks. She tried to stretch, but there just wasn't enough leg room for someone like her. -

The Top Dance Songs of 2019 1

th 45 Year THE TOP DANCE SONGS OF 2019 1. HIGHER LOVE – Kygo & Whitney Houston (RCA) 124/104 51. YOU LITTLE BEAUTY – Fisher (Astralwerks/Capitol) 124 2. PIECE OF YOUR HEART – Meduza ft. Goodboys (Capitol) 124 52. GO SLOW – Gorgon City & Kaskade ft. ROMEO (Capitol) 124 3. I DON’T CARE – Ed Sheeran & Justin Bieber (Atlantic) 122/102 53. SUMMER DAYS – Martin Garrix ft. Macklemore & Patrick Stump (RCA) 126/114 4. SUCKER – Jonas Brothers (Republic) 126/138 54. ON MY WAY – Alan Walker, Sabrina Carpenter & Farruko (RCA) 120/85 5. BAD GUY – Billie Eilish (Interscope) 126/135 55. HEY LOOK MA, I MADE IT – Panic! At The Disco (Atlantic) 124/108 6. CON CALMA – Daddy Yankee & Katy Perry ft. Snow (El Cartel/Capitol) 109/94 56. FIND U AGAIN – Mark Ronson & Camila Cabello (RCA) 124/104 7. SENORITA – Shawn Mendes & Camila Cabello (Republic) 124/117 57. BREAK UP WITH YOUR GIRLFRIEND, I’M BORED – Ariana Grande (Republic) 124/85 8. 7 RINGS/THANK U NEXT – Ariana Grande (Republic) 126/70, 124/107 58. SELFISH – Dimitri Vegas & Like Mike ft. Era Istrefi (Arista) 126/96 9. DANCING WITH A STRANGER – Sam Smith & Normani (Capitol) 123/103 59. 365 – Zedd & Katy Perry (Interscope) 124/98 10. DANCE MONKEY – Tones and I (Elektra) 122/98 60. BEAUTIFUL PEOPLE – Ed Sheeran ft. Khalid (Atlantic) 120/93 11. OLD TOWN ROAD – Lil Nas X ft. Billy Ray Cyrus (Columbia) 124/70 61. QUE CALOR – Major Lazer ft. J Balvin & El Alfa (Mad Decent) 126 12. SO CLOSE – NOTD & Felix Jaehn ft. Georgia Ku & Captain Cuts (Republic) 126 62. -

DJ Music Catalog by Title

Artist Title Artist Title Artist Title Dev Feat. Nef The Pharaoh #1 Kellie Pickler 100 Proof [Radio Edit] Rick Ross Feat. Jay-Z And Dr. Dre 3 Kings Cobra Starship Feat. My Name is Kay #1Nite Andrea Burns 100 Stories [Josh Harris Vocal Club Edit Yo Gotti, Fabolous & DJ Khaled 3 Kings [Clean] Rev Theory #AlphaKing Five For Fighting 100 Years Josh Wilson 3 Minute Song [Album Version] Tank Feat. Chris Brown, Siya And Sa #BDay [Clean] Crystal Waters 100% Pure Love TK N' Cash 3 Times In A Row [Clean] Mariah Carey Feat. Miguel #Beautiful Frenship 1000 Nights Elliott Yamin 3 Words Mariah Carey Feat. Miguel #Beautiful [Louie Vega EOL Remix - Clean Rachel Platten 1000 Ships [Single Version] Britney Spears 3 [Groove Police Radio Edit] Mariah Carey Feat. Miguel And A$AP #Beautiful [Remix - Clean] Prince 1000 X's & O's Queens Of The Stone Age 3's & 7's [LP] Mariah Carey Feat. Miguel And Jeezy #Beautiful [Remix - Edited] Godsmack 1000hp [Radio Edit] Emblem3 3,000 Miles Mariah Carey Feat. Miguel #Beautiful/#Hermosa [Spanglish Version]d Colton James 101 Proof [Granny With A Gold Tooth Radi Lonely Island Feat. Justin Timberla 3-Way (The Golden Rule) [Edited] Tucker #Country Colton James 101 Proof [The Full 101 Proof] Sho Baraka feat. Courtney Orlando 30 & Up, 1986 [Radio] Nate Harasim #HarmonyPark Wrabel 11 Blocks Vinyl Theatre 30 Seconds Neighbourhood Feat. French Montana #icanteven Dinosaur Pile-Up 11:11 Jay-Z 30 Something [Amended] Eric Nolan #OMW (On My Way) Rodrigo Y Gabriela 11:11 [KBCO Edit] Childish Gambino 3005 Chainsmokers #Selfie Rodrigo Y Gabriela 11:11 [Radio Edit] Future 31 Days [Xtra Clean] My Chemical Romance #SING It For Japan Michael Franti & Spearhead Feat. -

To Search This List, Hit CTRL+F to "Find" Any Song Or Artist Song Artist

To Search this list, hit CTRL+F to "Find" any song or artist Song Artist Length Peaches & Cream 112 3:13 U Already Know 112 3:18 All Mixed Up 311 3:00 Amber 311 3:27 Come Original 311 3:43 Love Song 311 3:29 Work 1,2,3 3:39 Dinosaurs 16bit 5:00 No Lie Featuring Drake 2 Chainz 3:58 2 Live Blues 2 Live Crew 5:15 Bad A.. B...h 2 Live Crew 4:04 Break It on Down 2 Live Crew 4:00 C'mon Babe 2 Live Crew 4:44 Coolin' 2 Live Crew 5:03 D.K. Almighty 2 Live Crew 4:53 Dirty Nursery Rhymes 2 Live Crew 3:08 Fraternity Record 2 Live Crew 4:47 Get Loose Now 2 Live Crew 4:36 Hoochie Mama 2 Live Crew 3:01 If You Believe in Having Sex 2 Live Crew 3:52 Me So Horny 2 Live Crew 4:36 Mega Mixx III 2 Live Crew 5:45 My Seven Bizzos 2 Live Crew 4:19 Put Her in the Buck 2 Live Crew 3:57 Reggae Joint 2 Live Crew 4:14 The F--k Shop 2 Live Crew 3:25 Tootsie Roll 2 Live Crew 4:16 Get Ready For This 2 Unlimited 3:43 Smooth Criminal 2CELLOS (Sulic & Hauser) 4:06 Baby Don't Cry 2Pac 4:22 California Love 2Pac 4:01 Changes 2Pac 4:29 Dear Mama 2Pac 4:40 I Ain't Mad At Cha 2Pac 4:54 Life Goes On 2Pac 5:03 Thug Passion 2Pac 5:08 Troublesome '96 2Pac 4:37 Until The End Of Time 2Pac 4:27 To Search this list, hit CTRL+F to "Find" any song or artist Ghetto Gospel 2Pac Feat. -

The Human Touch Vol.13

VOLUME 13 2020 The Human THE JOURNAL OF POETRY, Touch PROSE AND VISUAL ART UNIVERSITY OF COLORADO | ANSCHUTZ MEDICAL CAMPUS THE JOURNAL OF Poetry, Prose, & Visual Art University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus FRONT COVER ARTWORK Lattes For Two MICHAEL AUBREY BACK COVER ARTWORK Choice SUBBIAH PUGAZHENTHI GRAPHIC DESIGN Christina Martins [email protected] christinamartins.me PRINTING Bill Daley Citizen Printing, Fort Collins 970.545.0699 [email protected] This journal and all of its contents with no exceptions are covered under the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. To view a summary of this license, please see http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/us/. To review the license in full, please see http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/us/legalcode. Fair use and other rights are not affected by this license. To learn more about this and other Creative Commons licenses, please see http://creativecommons.org/about/licenses/meet-the-licenses. To honor the creative expression of the journal’s contributors, the unique and deliberate formats of their work have been preserved. © All Authors/Artists Hold Their Own Copyright THE HUMAN TOUCH Volume 13 2020 EDITORS IN CHIEF Allison M. Dubner Carolyn Ho Priya Krishnan EDITORIAL BOARD MEMBERS Nicholas Arlas James Carter Amelia Davis Anjali Dhurandhar Nina Elder Kirk Fetters Lynne Fox Robyn Gisbert Amanda Glickman George Ho Vladka Kovar Diana Lutfi Jenna Pratt Kelly Stanek David Weil Helena Winston SUPERVISING EDITOR Therese -

Touch the Human

VOLUME 13 2020 The Human THE JOURNAL OF POETRY, Touch PROSE AND VISUAL ART UNIVERSITY OF COLORADO | ANSCHUTZ MEDICAL CAMPUS THE JOURNAL OF Poetry, Prose, & Visual Art University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus FRONT COVER ARTWORK Lattes For Two MICHAEL AUBREY BACK COVER ARTWORK Choice SUBBIAH PUGAZHENTHI GRAPHIC DESIGN Christina Martins [email protected] christinamartins.me PRINTING Bill Daley Citizen Printing, Fort Collins 970.545.0699 [email protected] This journal and all of its contents with no exceptions are covered under the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. To view a summary of this license, please see http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/us/. To review the license in full, please see http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/us/legalcode. Fair use and other rights are not affected by this license. To learn more about this and other Creative Commons licenses, please see http://creativecommons.org/about/licenses/meet-the-licenses. To honor the creative expression of the journal’s contributors, the unique and deliberate formats of their work have been preserved. © All Authors/Artists Hold Their Own Copyright THE HUMAN TOUCH Volume 13 2020 EDITORS IN CHIEF Allison M. Dubner Carolyn Ho Priya Krishnan EDITORIAL BOARD MEMBERS Nicholas Arlas James Carter Amelia Davis Anjali Dhurandhar Nina Elder Kirk Fetters Lynne Fox Robyn Gisbert Amanda Glickman George Ho Vladka Kovar Diana Lutfi Jenna Pratt Kelly Stanek David Weil Helena Winston SUPERVISING EDITOR Therese -

Here Research Corporation

The Rubber Glove Theory of the Universe, and Other Diversions By: Walter Shawlee 2 Sphere Research Corporation Contents Copyright: 1994, 2000, 2001, 2006, 2009, 2010 by Sphere Research Corporation All Rights Reserved Cover Photo courtesy of the ISS/NASA ISBN: 978-0-557-36993-5 Available though LuLu.com Also http://www.sphere.bc.ca/document.html Page 1 Contents Before... Warcorp Miranda Father & Son Images Surplus Store Evening Kiss The Rubber Glove Theory of the Universe Magic Vacation Small Signs Maxine PRA Night Event Into the Dark The Man on the Beach Feelings When the Music’s Over After... The Black Path Page 2 Before: hort stories have one truly redeeming value. They let you explore something interesting without making you wade through 350 S questionable pages in order to actually do that simple task. Not so unexpectedly, their most irritating feature is that they may end just as you are starting to feel right at home there. Well, I just can’t help that part; short stories are, after all, short. These stories are a series of small commando forays into the global bureaucracy of the future, a private look inside the mind of an ancient king, a quick but hopefully cogent explanation of how the universe really works and a field exercise in practical magic. You will get a chance to poke around in the future courtesy of a convenient motel room, die in several very unpleasant ways, and hopefully feel your heart break. You will visit life after death here, encounter voodoo criminals and maybe fall in love with a machine.