Giovanni Boldini

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Master of the Unruly Children and His Artistic and Creative Identities

The Master of the Unruly Children and his Artistic and Creative Identities Hannah R. Higham A Thesis Submitted to The University of Birmingham For The Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of Art History, Film and Visual Studies School of Languages, Art History and Music College of Arts and Law The University of Birmingham May 2015 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT This thesis examines a group of terracotta sculptures attributed to an artist known as the Master of the Unruly Children. The name of this artist was coined by Wilhelm von Bode, on the occasion of his first grouping seven works featuring animated infants in Berlin and London in 1890. Due to the distinctive characteristics of his work, this personality has become a mainstay of scholarship in Renaissance sculpture which has focused on identifying the anonymous artist, despite the physical evidence which suggests the involvement of several hands. Chapter One will examine the historiography in connoisseurship from the late nineteenth century to the present and will explore the idea of the scholarly “construction” of artistic identity and issues of value and innovation that are bound up with the attribution of these works. -

INDICE 1) Comunicato Stampa 2) Scheda Tecnica 3) Selezione Opere

INDICE 1) Comunicato stampa 2) Scheda tecnica 3) Selezione opere per la stampa 4) Vademecum della mostra di Carlo Falciani e Antonio Natali 5) “Lascivia” e “divozione”. Arte a Firenze nella seconda metà del Cinquecento: introduzione dei curatori della mostra Carlo Falciani, Antonio Natali 6) Introduzione alla mostra del Direttore della Fondazione Palazzo Strozzi, Arturo Galansino 7) Dieci motivi per non perdere la mostra “Il Cinquecento a Firenze” APPROFONDIMENTI Gli importanti restauri realizzati per la mostra La mostra in numeri 8) Attività in mostra e oltre 9) Elenco delle opere 10) Cronologia COMUNICATO STAMPA Il Cinquecento a Firenze “maniera moderna” e controriforma. Tra Michelangelo, Pontormo e Giambologna Palazzo Strozzi, 21 settembre 2017-21 gennaio 2018 #500Firenze Un evento irripetibile e unico, ultimo atto della trilogia sulla “maniera” di Palazzo Strozzi, che vede riuniti per la prima volta capolavori assoluti di Michelangelo, Andrea del Sarto, Rosso Fiorentino, Bronzino, Giorgio Vasari, Santi di Tito, Giambologna, provenienti dall’Italia e dall’estero, molti dei quali restaurati per l’occasione. Dal 21 settembre 2017 al 21 gennaio 2018 Palazzo Strozzi ospita Il Cinquecento a Firenze, una straordinaria mostra dedicata all’arte del secondo Cinquecento a Firenze. Ultimo atto d’una trilogia di mostre a Palazzo Strozzi a cura di Carlo Falciani e Antonio Natali, iniziata con Bronzino nel 2010 e Pontormo e Rosso Fiorentino nel 2014, la rassegna celebra un’eccezionale epoca culturale e di estro intellettuale, in un confronto serrato tra “maniera moderna” e controriforma, tra sacro e profano: una stagione unica per la storia dell’arte, segnata dal concilio di Trento e dalla figura di Francesco I de’ Medici, uno dei più geniali rappresentanti del mecenatismo di corte in Europa. -

Coexistence of Mythological and Historical Elements

COEXISTENCE OF MYTHOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL ELEMENTS AND NARRATIVES: ART AT THE COURT OF THE MEDICI DUKES 1537-1609 Contents Introduction ........................................................................................................................................................ 3 Greek and Roman examples of coexisting themes ........................................................................ 6 1. Cosimo’s Triumphal Propaganda ..................................................................................................... 7 Franco’s Battle of Montemurlo and the Rape of Ganymede ........................................................ 8 Horatius Cocles Defending the Pons Subicius ................................................................................. 10 The Sacrificial Death of Marcus Curtius ........................................................................................... 13 2. Francesco’s parallel narratives in a personal space .............................................................. 16 The Studiolo ................................................................................................................................................ 16 Marsilli’s Race of Atalanta ..................................................................................................................... 18 Traballesi’s Danae .................................................................................................................................... 21 3. Ferdinando’s mythological dream ............................................................................................... -

Vezzosi A. Sabato A. the New Genealogical Tree of the Da Vinci

HUMAN EVOLUTION Vol. 36 - n. 1-2 (1-90) - 2021 Vezzosi A. The New Genealogical Tree of the Da Vinci Leonardo scholar, art historian Family for Leonardo’s DNA. Founder of Museo Ideale Leonardo Da Vinci Ancestors and descendants in direct male Via IV Novembre 2 line down to the present XXI generation* 50059 Vinci (FI), Italy This research demonstrates in a documented manner the con- E-mail: [email protected] tinuity in the direct male line, from father to son, of the Da Vinci family starting with Michele (XIV century) to fourteen Sabato A. living descendants through twenty-one generations and four Historian, writer different branches, which from the XV generation (Tommaso), President of Associazione in turn generate other line branches. Such results are eagerly Leonardo Da Vinci Heritage awaited from an historical viewpoint, with the correction of the E-mail: leonardodavinciheritage@ previous Da Vinci trees (especially Uzielli, 1872, and Smiraglia gmail.com Scognamiglio, 1900) which reached down to and hinted at the XVI generation (with several errors and omissions), and an up- DOI: 10.14673/HE2021121077 date on the living. Like the surname, male heredity connects the history of regis- try records with biological history along separate lineages. Be- KEY WORDS: Leonardo Da Vinci, cause of this, the present genealogy, which spans almost seven Da Vinci new genealogy, ancestors, hundred years, can be used to verify, by means of the most living descendants, XXI generations, innovative technologies of molecular biology, the unbroken Domenico di ser Piero, Y chromosome, transmission of the Y chromosome (through the living descend- Florence, Bottinaccio (Montespertoli), ants and ancient tombs, even if with some small variations due burials, Da Vinci family tomb in Vinci, to time) with a view to confirming the recovery of Leonardo’s Santa Croce church in Vinci, Ground Y marker. -

Cellini Vs Michelangelo: a Comparison of the Use of Furia, Forza, Difficultà, Terriblità, and Fantasia

International Journal of Art and Art History December 2018, Vol. 6, No. 2, pp. 22-30 ISSN: 2374-2321 (Print), 2374-233X (Online) Copyright © The Author(s).All Rights Reserved. Published by American Research Institute for Policy Development DOI: 10.15640/ijaah.v6n2p4 URL: https://doi.org/10.15640/ijaah.v6n2p4 Cellini vs Michelangelo: A Comparison of the Use of Furia, Forza, Difficultà, Terriblità, and Fantasia Maureen Maggio1 Abstract: Although a contemporary of the great Michelangelo, Benvenuto Cellini is not as well known to the general public today. Cellini, a master sculptor and goldsmith in his own right, made no secret of his admiration for Michelangelo’s work, and wrote treatises on artistic principles. In fact, Cellini’s artistic treatises can be argued to have exemplified the principles that Vasari and his contemporaries have attributed to Michelangelo. This paper provides an overview of the key Renaissance artistic principles of furia, forza, difficultà, terriblità, and fantasia, and uses them to examine and compare Cellini’s famous Perseus and Medusa in the Loggia deiLanzi to the work of Michelangelo, particularly his famous statue of David, displayed in the Galleria dell’ Accademia. Using these principles, this analysis shows that Cellini not only knew of the artistic principles of Michelangelo, but that his work also displays a mastery of these principles equal to Michelangelo’s masterpieces. Keywords: Cellini, Michelangelo, Renaissance aesthetics, Renaissance Sculptors, Italian Renaissance 1.0Introduction Benvenuto Cellini was a Florentine master sculptor and goldsmith who was a contemporary of the great Michelangelo (Fenton, 2010). Cellini had been educated at the Accademiade lDisegno where Michelangelo’s artistic principles were being taught (Jack, 1976). -

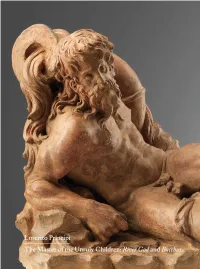

The Master of the Unruly Children: River God and Bacchus TRINITY

TRINITY FINE ART Lorenzo Principi The Master of the Unruly Children: River God and Bacchus London February 2020 Contents Acknowledgements: Giorgio Bacovich, Monica Bassanello, Jens Burk, Sara Cavatorti, Alessandro Cesati, Antonella Ciacci, 1. Florence 1523 Maichol Clemente, Francesco Colaucci, Lavinia Costanzo , p. 12 Claudia Cremonini, Alan Phipps Darr, Douglas DeFors , 2. Sandro di Lorenzo Luizetta Falyushina, Davide Gambino, Giancarlo Gentilini, and The Master of the Unruly Children Francesca Girelli, Cathryn Goodwin, Simone Guerriero, p. 20 Volker Krahn, Pavla Langer, Guido Linke, Stuart Lochhead, Mauro Magliani, Philippe Malgouyres, 3. Ligefiguren . From the Antique Judith Mann, Peta Motture, Stefano Musso, to the Master of the Unruly Children Omero Nardini, Maureen O’Brien, Chiara Padelletti, p. 41 Barbara Piovan, Cornelia Posch, Davide Ravaioli, 4. “ Bene formato et bene colorito ad imitatione di vero bronzo ”. Betsy J. Rosasco, Valentina Rossi, Oliva Rucellai, The function and the position of the statuettes of River God and Bacchus Katharina Siefert, Miriam Sz ó´cs, Ruth Taylor, Nicolas Tini Brunozzi, Alexandra Toscano, Riccardo Todesco, in the history of Italian Renaissance Kleinplastik Zsófia Vargyas, Laëtitia Villaume p. 48 5. The River God and the Bacchus in the history and criticism of 16 th century Italian Renaissance sculpture Catalogue edited by: p. 53 Dimitrios Zikos The Master of the Unruly Children: A list of the statuettes of River God and Bacchus Editorial coordination: p. 68 Ferdinando Corberi The Master of the Unruly Children: A Catalogue raisonné p. 76 Bibliography Carlo Orsi p. 84 THE MASTER OF THE UNRULY CHILDREN probably Sandro di Lorenzo di Smeraldo (Florence 1483 – c. 1554) River God terracotta, 26 x 33 x 21 cm PROVENANCE : heirs of the Zalum family, Florence (probably Villa Gamberaia) THE MASTER OF THE UNRULY CHILDREN probably Sandro di Lorenzo di Smeraldo (Florence 1483 – c. -

Leon Battista Alberti

THE HARVARD UNIVERSITY CENTER FOR ITALIAN RENAISSANCE STUDIES VILLA I TATTI Via di Vincigliata 26, 50135 Florence, Italy VOLUME 25 E-mail: [email protected] / Web: http://www.itatti.ita a a Tel: +39 055 603 251 / Fax: +39 055 603 383 AUTUMN 2005 From Joseph Connors: Letter from Florence From Katharine Park: he verve of every new Fellow who he last time I spent a full semester at walked into my office in September, I Tatti was in the spring of 2001. It T This year we have two T the abundant vendemmia, the large was as a Visiting Professor, and my Letters from Florence. number of families and children: all these husband Martin Brody and I spent a Director Joseph Connors was on were good omens. And indeed it has been splendid six months in the Villa Papiniana sabbatical for the second semester a year of extraordinary sparkle. The bonds composing a piano trio (in his case) and during which time Katharine Park, among Fellows were reinforced at the finishing up the research on a book on Zemurray Stone Radcliffe Professor outset by several trips, first to Orvieto, the medieval and Renaissance origins of of the History of Science and of the where we were guided by the great human dissection (in mine). Like so Studies of Women, Gender, and expert on the cathedral, Lucio Riccetti many who have worked at I Tatti, we Sexuality came to Florence from (VIT’91); and another to Milan, where were overwhelmed by the beauty of the Harvard as Acting Director. Matteo Ceriana guided us place, impressed by its through the exhibition on Fra scholarly resources, and Carnevale, which he had helped stimulated by the company to organize along with Keith and conversation. -

Gender Dynamics in Renaissance Florence Mary D

Early Modern Women: An Interdisciplinary Journal Vol. 11, No. 1 • Fall 2016 The Cloister and the Square: Gender Dynamics in Renaissance Florence Mary D. Garrard eminist scholars have effectively unmasked the misogynist messages of the Fstatues that occupy and patrol the main public square of Florence — most conspicuously, Benvenuto Cellini’s Perseus Slaying Medusa and Giovanni da Bologna’s Rape of a Sabine Woman (Figs. 1, 20). In groundbreaking essays on those statues, Yael Even and Margaret Carroll brought to light the absolutist patriarchal control that was expressed through images of sexual violence.1 The purpose of art, in this way of thinking, was to bolster power by demonstrating its effect. Discussing Cellini’s brutal representation of the decapitated Medusa, Even connected the artist’s gratuitous inclusion of the dismembered body with his psychosexual concerns, and the display of Medusa’s gory head with a terrifying female archetype that is now seen to be under masculine control. Indeed, Cellini’s need to restage the patriarchal execution might be said to express a subconscious response to threat from the female, which he met through psychological reversal, by converting the dangerous female chimera into a feminine victim.2 1 Yael Even, “The Loggia dei Lanzi: A Showcase of Female Subjugation,” and Margaret D. Carroll, “The Erotics of Absolutism: Rubens and the Mystification of Sexual Violence,” The Expanding Discourse: Feminism and Art History, ed. Norma Broude and Mary D. Garrard (New York: HarperCollins, 1992), 127–37, 139–59; and Geraldine A. Johnson, “Idol or Ideal? The Power and Potency of Female Public Sculpture,” Picturing Women in Renaissance and Baroque Italy, ed. -

The Ashgate Research Companion to Giorgio Vasari Vasari and Vincenzo

This article was downloaded by: 10.3.98.104 On: 26 Sep 2021 Access details: subscription number Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: 5 Howick Place, London SW1P 1WG, UK The Ashgate Research Companion to Giorgio Vasari David J. Cast Vasari and Vincenzo Borghini Publication details https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/doi/10.4324/9781315613017.ch2 Robert Williams Published online on: 28 Dec 2013 How to cite :- Robert Williams. 28 Dec 2013, Vasari and Vincenzo Borghini from: The Ashgate Research Companion to Giorgio Vasari Routledge Accessed on: 26 Sep 2021 https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/doi/10.4324/9781315613017.ch2 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR DOCUMENT Full terms and conditions of use: https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/legal-notices/terms This Document PDF may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproductions, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The publisher shall not be liable for an loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material. 2 Vasari and Vincenzo Borghini Robert Williams Vasari’s association with Don Vincenzo (or Vincenzio) Borghini, the Benedictine monk and scholar who was also one of Duke Cosimo de’ Medici’s most trusted advisors and civil servants, stretched from at least the end of the 1540s until the artist’s death in 1574. -

Florence Celebrates the Uffizi the Medici Were Acquisitive, but the Last of the Line Was Generous

ArtNews December 1982 Florence Celebrates The Uffizi The Medici were acquisitive, but the last of the line was generous. She left all the family’s treasures to the people of Florence. by Milton Gendel Whenever I vist The Uffizi Gallery, I start with Raphael’s classic portrait of Leo X and Two Cardinals, in which the artist shows his patron and friend as a princely pontiff at home in his study. The pope’s esthetic interests are indicated by the finely worked silver bell on the red-draped table and an illuminated Bible, which he has been studying with the aid of a gold-mounted lens. The brass ball finial on his chair alludes to the Medici armorial device, for Leo X was Giovanni de’ Medici, the second son of Lorenzo the Magnificent. Clutching the chair, as if affirming the reality of nepotism, is the pope’s cousin, Cardinal Luigi de’ Rossi. On the left is Cardinal Giulio de’ Medici, another cousin, whose look of reverie might be read, I imagine, as foreseeing his own disastrous reign as Pope Clement VII. That was five years in the future, of course, and could not have been anticipated by Raphael, but Leo had also made cardinals of his three nephews, so it wasn’t unlikely that another member of the family would be elected to the papacy. In fact, between 1513 and 1605, four Medici popes reigned in Rome. Leo X was a true Renaissance prince, whose civility and love of the arts impressed everyone - in the tradition of his father, Lorenzo the Magnificent. -

Celebrating the City: the Image of Florence As Shaped Through the Arts

“Nothing more beautiful or wonderful than Florence can be found anywhere in the world.” - Leonardo Bruni, “Panegyric to the City of Florence” (1403) “I was in a sort of ecstasy from the idea of being in Florence.” - Stendahl, Naples and Florence: A Journey from Milan to Reggio (1817) “Historic Florence is an incubus on its present population.” - Mary McCarthy, The Stones of Florence (1956) “It’s hard for other people to realize just how easily we Florentines live with the past in our hearts and minds because it surrounds us in a very real way. To most people, the Renaissance is a few paintings on a gallery wall; to us it is more than an environment - it’s an entire culture, a way of life.” - Franco Zeffirelli Celebrating the City: the image of Florence as shaped through the arts ACM Florence Fall, 2010 Celebrating the City, page 2 Celebrating the City: the image of Florence as shaped through the arts ACM Florence Fall, 2010 The citizens of renaissance Florence proclaimed the power, wealth and piety of their city through the arts, and left a rich cultural heritage that still surrounds Florence with a unique and compelling mystique. This course will examine the circumstances that fostered such a flowering of the arts, the works that were particularly created to promote the status and beauty of the city, and the reaction of past and present Florentines to their extraordinary home. In keeping with the ACM Florence program‟s goal of helping students to “read a city”, we will frequently use site visits as our classroom. -

Profiling Women in Sixteenth-Century Italian

BEAUTY, POWER, PROPAGANDA, AND CELEBRATION: PROFILING WOMEN IN SIXTEENTH-CENTURY ITALIAN COMMEMORATIVE MEDALS by CHRISTINE CHIORIAN WOLKEN Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Dissertation Advisor: Dr. Edward Olszewski Department of Art History CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERISTY August, 2012 CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES We hereby approve the thesis/dissertation of Christine Chiorian Wolken _______________________________________________________ Doctor of Philosophy Candidate for the __________________________________________ degree*. Edward J. Olszewski (signed) _________________________________________________________ (Chair of the Committee) Catherine Scallen __________________________________________________________________ Jon Seydl __________________________________________________________________ Holly Witchey __________________________________________________________________ April 2, 2012 (date)_______________________ *We also certify that written approval has been obtained for any proprietary material contained therein. 1 To my children, Sofia, Juliet, and Edward 2 Table of Contents List of Images ……………………………………………………………………..….4 Acknowledgements……………………………………………………………...…..12 Abstract……………………………………………………………………………...15 Introduction…………………………………………………………………………16 Chapter 1: Situating Sixteenth-Century Medals of Women: the history, production techniques and stylistic developments in the medal………...44 Chapter 2: Expressing the Link between Beauty and