2016 Final Report Appendices (Part B)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 INSEAD 2 Indian Institute of Management Ahmedabad 3

1 INSEAD 2 Indian Institute of Management Ahmedabad 3 Melbourne Business School The University of Melbourne 4 NUS Business School, National University of Singapore (NUS) NUS Business School National University of Singapore (NUS) 5 Indian Institute of Management Bangalore 6 Indian School of Business 7 BiMBA: Beijing International MBA Peking University 8 AGSM MBA Programs University of New South Wales 9 Indian Institute of Management Calcutta 10 Nanyang Business School Nanyang Technological University 12 HKUST Business SchoolHKUST Business School 13 Macquarie Graduate School of Management (MGSM), Macquarie University Macquarie Graduate School of Management (MGSM) Macquarie University 14 ANU College of Business and Economics The Australian National University 15 Sydney Business School, University of WollongongSydney Business School University of Wollongong 16 Fudan University - School of Management Fudan University 17 Faculty of Business and Economics Monash University 18 CUHK Business SchoolCUHK Business School 19 Faculty of Business and Economics, The University of Hong KongFaculty of Business and Economics The University of Hong Kong 20 Graduate School of Business Seoul National University 21 Tsinghua University School of Economics & Management 22 The University of Adelaide - Business School The University of Adelaide 23 La Trobe Business School, La Trobe UniversityLa Trobe Business School La Trobe University 24 Asian Institute of Management- W. Sycip Graduate School of Management 25 Waseda Business School Waseda University 26 Peking -

Should I Stay Or Should I Go?* Isep

ISEP INTERNATIONAL STUDENT EXCHANGE PROGRAMME SHOULD I STAY OR ACCESS A WIDER NETWORK OF UNIVERSITIES ACROSS THE GLOBE SHOULD I GO?* ESSEX IS NOW A MEMBER OF THE INTERNATIONAL STUDENT EXCHANGE PROGRAM (ISEP). ISEP IS A US BASED PROVIDER WHICH OFFERS A BROADER EXCHANGE NETWORK COMPRISING OF OVER 200 PARTICIPATING UNIVERSITIES GLOBALLY. GO ABROAD AND DEVELOP INDEPENDENCE, TOLERANCE, ADAPTABILITY, CONFIDENCE AND A GLOBAL OUTLOOK. *You should go HOW DOES IT WORK? Programme Fee IS IT FOR ME? If you apply to study abroad with ISEP, This fee is paid directly to Essex. It covers ISEP is a great study abroad option to you won’t be able to apply to Essex Abroad’s fees, housing, 19 meals per week, consider. It offers you: exchange programme. Your application pre-departure orientation, arrival orientation is made online and you can select up to and general student services at your host n A wider network of universities, with some OUR PARTNER UNIVERSITIES 10 universities. institution. Costs can vary annually, in in counties/regions where Essex may not 2018/19 Essex students studying abroad have exchange partners Subject area Subject area COSTS INVOLVED through ISEP for the full academic year paid £7,100. n A stronger chance of securing a place in AUSTRALIA AND NEW ZEALAND ASIA Application fee more competitive destinations (typically By doing this, you are creating a ‘space’ for AUSTRALIA JAPAN This is a non-refundable fee of $100 paid Australia, USA, Canada and New Zealand) an exchange student who comes to Essex. All* directly to ISEP. Curtin University Akita International University All* When you arrive at your host institution you n A sometimes more cost-effective study La Trobe University All* International Christian University All* will have guaranteed accommodation and a Placement Fee abroad experience if choosing to study in Monash University All* Tokyo University of Foreign Studies All* food plan for the time you are there. -

Institute Director of Future Cities Research Institute

Institute Director of Future Cities Research Institute Candidate Pack May 2019 Closing Date: Thursday 18 July 2019 | Ref: A2688 Institute Director of Future Cities Research Institute Building on the success of the longstanding The vision is for FCRI to become self- Lancaster University - Sunway University sustaining within 5 years following the initial partnership and our shared interest in cities funding period, and sustainability of the research our institutions are creating a new, institute activities will be a substantial part of joint Future Cities Research Institute (FCRI). the Director’s role. You will also contribute to the academic development of FCRI and to Lancaster and Sunway have had an academic the enhancement of Lancaster and Sunway partnership since 2006, with a number of University’s global profile and reputation. joint degree courses and successful research collaborations. The creation of a new, joint The post will be based at the Sunway institute in cities research between Lancaster campus in Malaysia but with regular travel to and Sunway builds on existing strengths Lancaster in the UK. across the two institutions, complementing You must have good knowledge of Southeast the work of the Jeffrey Sachs Center on Asia culture and be aware of the UK research Sustainable Development (based at Sunway landscape. University), and maximising the impact of the wide variety of relevant, world-leading Formal interviews will take place on the research undertaken at Lancaster University. Sunway campus, in September 2019 and it It will strengthen and expand research is expected that candidates will be able to partnerships between the two institutions. travel to Malaysia for this. -

Global Executive MBA Engages with Global Firms in Its Content, Partnerships and Projects

CHINAINDIAUNITEDSTATESINDONESIABRAZILPAKISTANNI- GERIABANGLADESHRUSSIAJAPANMEXICOETHIOPIAPHILIP- PINESEGYPTVIETNAMTHEDEMOCRATICREPUBLICOFCON- GOIRANTURKEYGERMANYTHAILANDFRANCEUNITEDKINGMONASH - DOMITALYBURMASOUTHAFRICATANZANIAKOREASOUTHBUSINESS - SPAINCOLOMBIAKENYAARGENTINAUKRAINEALGERIAUGAN- DAIRAQPOLANDSUDANCANADAAFGHANISTANMOROCCOMASCHOOL - LAYSIAVENEZUELAPERUUZBEKISTANNEPALANGOLASAU- DIARABIAYEMENGHANAMOZAMBIQUEKOREANORTHMADA- GASCARCAMEROONCOTEDIVOIRETAIWANAUSTRALIASRIL- ANKAROMANIABURKINAFASONIGERMALAWIKAZAKHSTAN- SYRIAMALICHILENETHERLANDSECUADORCAMBODIAZAM- BIAGUATEMALASENEGALZIMBABWESOUTHSUDANGUINE- ACHADRWANDABELGIUMBURUNDITUNISIACUBABOLIVIABE- NINSOMALIAPORTUGALGREECEDOMINICANREPUBLICCZE- CHIAHAITIJORDANAZERBAIJANSWEDENHUNGARYBELAR- USHONDURASAUSTRIATAJIKISTANISRAELSWITZERLAND- TOGOHONGKONGLAOSSERBIABULGARIAPARAGUAYPAPUAN- EWGUINEALIBYALEBANONELSALVADORSIERRALEONEUNITE- DARABEMIRATESNICARAGUAERITREASINGAPOREKYRGYZ- STANCENTRALAFRICANREPUBLICDENMARKFINLANDSLOVA- KIATURKMENISTANNORWAYIRELANDTHEREPUBLICOFCON- GOCOSTARICAGEORGIALIBERIANEWZEALANDCROATIABOS- NIAANDHERZEGOVINAMAURITANIAPANAMAMOLDOVAOMA- NURUGUAYPUERTORICOMONGOLIAALBANIAARMENIAJA- MAICAKUWAITLITHUANIAWESTBANKNAMIBIAQATARBO- TSWANAMACEDONIAGAMBIATHESLOVENIALESOTHOLATVIA- KOSOVOGAZASTRIPGUINEABISSAUGABONSWAZILANDBAH- RAINMAURITIUSTIMORLESTEESTONIACYPRUSTRINIDADAN- GLOBAL DTOBAGOFIJIDJIBOUTICOMOROSEQUATORIALGUINEABHU- TANGUYANASOLOMONISLANDSMONTENEGROWESTERNSA- EXECUTIVE HARAMACAULUXEMBOURGSURINAMECABOVERDEBRUNEI- MALTAMALDIVESBELIZEICELANDTHEBAHAMASBARBADOS- MBA FRENCHPOLYNESIAVANUATUNEWCALEDONIASAOTOMEAN- -

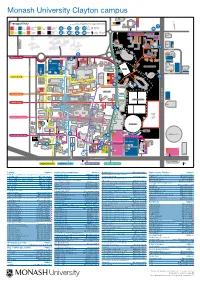

Monash University Clayton Campus

Monash University Clayton campus 56 For a more detailed Campus map, visit: monash.edu/people/maps Transport Key For the latest permit information please refer to parking signs in local area Electric 101 Hourly/Daily Residential HOWLEYS ROAD Red Blue Motorcycle Car Bus Taxi Emergency Meter Services Vehicle Permit Permit Parking parking Help Points Parking Parking Charging 10 Authorised NORMANBY ROAD Yellow Green Accessible 1/2P Drop off/ Bicycle Share Loading Security Parking Parking 1 M Permit Permit Parking Parking Pick Up Arrival Cars Dock Bus Stop Meter Only Station 680 ONE WAY ONE 8 6 60 63 9 61 SCENIC BOULEVARD 58 COLLEGE WAY COLLEGE 62 700 8 264 FERNTREE GULLY ROAD 56 MARTIN ST Aboriginal Garden GARDINER ROAD 710 BAYVIEW AVENUE RESEARCH WAY RESEARCH WAY 4 RESEARCH WAY 28 10 20 24 50 52 54 Multi-level 30 New Horizons 26 ROAD N2 52–70 Jock Marshall Reserve BOILER HOUSE ROAD 13 738 MRS UC Permit 22 valid in Blue Hockey 11 RAINFOREST WALK INNOVATION WALK BEDDOE AVE BOUNDARY 18 2 95 3 M DUERDIN ST Northern EXHIBITION WALK NATURE WALK Loading ALLIANCE LANE Area Woodside 21 COLLEGE WALK 44 17 Building 17 14 15 7 C5 9 42 ALLIANCE LANE 22 38 18 3 16 20 20 Earth Sciences Garden 11 Hargrave- 19 21 Green 13 Andrew 10 23 Chemical Library 13 Futures 17 Campus Park 3 COLLEGE WALK COLLEGE WALK Tennnis 10 14 28 Lemon 25 Scented 12 15 16 Lawn 21 27 Synthetic Sports Fields 15 Sound Shell 17 Doug Ellis BLACKBURN ROAD SPORTS WALK SPORTS WALK Swimming 19 Northern Plaza 28 Pool 770 24 36 23 22 32 21 BOUNDARY ROAD 26 34 2 18 25 19 Religious Campus Monash -

Workshop Program

SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT A workshop hosted by the Monash Business and Sustainability Network and Centre for Development Economics and Sustainability June 24-25, 2016 Venue: Monash University Prato Centre DRAFT PROGRAM DAY 1: FRIDAY, JUNE 24TH, 2016 8.45-9.00 Registration 9.00-9.15 Opening: Gary Magee (Deputy Dean Research, Monash Business School and Chair of the Monash Business & Sustainability Network, Monash University, Australia) Sisira Jayasuriya (Convener of the Economics Stream and Director, Centre for Development Economics & Sustainability, Monash University, Australia) Amrik Sohal (Convener of the Business Stream, Monash University, Australia) 9.15-11.00 Plenary 1: Global Economy and Prospects for Asia and Emerging Markets Chair: Keynote Address: Andrea E. Goldstein (Catholic University in Milan, Italy. Until recently Andrea was at the OECD Investment Division in charge of Global Relations) Topic: Panel discussion: 1. Ugo Panizza (Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies, Geneva, Switzerland) 2. Heinz Zeller (Senior Executive – Sustainability Leader, Hugo Boss) 3. Amy Auster (Monash University, Australia) 4. Rod Maddock (Monash University, Australia) 11.00-11.15 Morning Tea 1 11.15-12.45 Economics Stream Business Stream Session 1: Development Issues in Africa Session 1: Sustainability and Competitive Advantage Chair: Susan Olivia (Monash University, Australia) Chair: Amrik Sohal (Monash University, Australia) 1. Tilman Bruck (International Security and 1. Gerald Reiner (University of Klagenfurt, Development Center, Berlin, Germany): Austria): Competitive advantage through Determinants of refugee flows to sustainable resource efficiency Europe 2. Antonella Moretto et al. (Politecnico di Milano, 2. Ian Coxhead (University of Wisconsin- Italy): A roadmap towards a sustainable supply Madison, USA): Does freer trade really lead chain: steps and impacts on performance to productivity growth? Evidence from Africa 3. -

International Partner Universities Australia Griffith University, Gold Coast Monash University, Melbourne University of Newcastl

International Partner Universities Hong Kong Sweden City University of Hong Kong, Kowloon Jönkoping University, Jönkoping Australia Luleå University of Technology, Luleå Griffith University, Gold Coast Hungary Monash University, Melbourne ESSCA School of Management, Budapest Taiwan University of Newcastle, Newcastle National Taiwan Ocean University, Taiwan University of Technology Sydney (UTS), Sydney India RMIT University, Melbourne Indian Institute of Technology Madras (IITM), Uruguay Queensland University of Technology(QUT), Brisbane Chennai** University of Montevideo, Montevideo Western Sydney University, Rydalmere Ireland Vietnam Austria National University of Ireland, Galway RMIT University, Ho Chi Minh City Upper Austria University of Applied Sciences, Steyr and Wels Italy *Study only University of Bologna, Bologna** **Research only Canada Sant'Anna Institute, Sorrento* Laval University, Quebec City Politecnico di Torino, Turin** Sapienza University, Rome** China ESSCA School of Management, Shanghai Japan Ocean University of China, Qingdao** Kyushu Institute of Technology, Fukuoka** Shanghai University of Electric Power, Shanghai** Tsinghua University School of Materials Science and Mexico Engineering, Beijing** University of Monterrey, Monterrey Tecnologico de Monterrey, Mexico City Croatia University of Rijeka, Rijeka Netherlands Delft University of Technology, Delft Denmark Technical University of Denmark (DTU), Lyngby New Zealand AUT University, Auckland England Northumbria University, Newcastle-Upon-Tyne Romania University -

Monash University UF Exchange Flyer

UFExchange Monash University Melbourne, Australia The University of Florida’s College of Liberal Arts and Sciences offers students the opportunity to study in Melbourne, Australia at Monash University. Students can study Fast Facts during the fall, spring, or academic year. Founded: 1958 Enrollment: 60,000+ About the University Type: Public Research University Monash University is ranked in the world’s top 100 universities by QS World Ranking and is a member of the prestigious Group of Eight, a coalition of Australia’s largest and oldest universities that are consistently ranked highest of all Australian universities. Monash is in Melbourne, but they also have a Malaysia campus, which is open to UF students. Requirements/Eligibility • Open to all CLAS and CALS majors (Science majors, including pre-med/dental/vet students, are encouraged to apply) • Required GPA: 3.0 • Students must have completed 12 hours of coursework at UF • Two letters of recommendation (No family members or personal friends) • Official Transcript • Statement of Purpose • Interview with Dr. Brian Harfe, CLAS Associate Dean • Each applicant must be nominated by UF and then apply to the exchange partner as an international exchange student Location Melbourne, Victoria, is a vibrant city in Southeastern Australia. This is the place to be if you want a diverse mix of city and nature! You can do everything here, from relaxing on beaches, to visiting museums, and shopping at local markets. Situated right next to the Great Ocean Road, Melbourne is the perfect city to explore. Housing Exchange students are offered a range of accomodation options to suit different personalities, budgets, and lifestyles. -

Nicholas Sheard November 2018

NICHOLAS SHEARD NOVEMBER 2018 Centre of Policy Studies, Victoria University [email protected] Level 14, 300 Flinders Street sites.google.com/site/nicholassheard Melbourne, VIC, 3000 Australia EMPLOYMENT 2018 – present Research Fellow, Centre of Policy Studies, Victoria University 2017 – 2018 Associate Lecturer, University of Liverpool 2017 – 2018 Researcher, Centre for Economic Research, Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU) 2015 – 2017 Postdoctoral Fellow, Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU) 2012 – 2015 Postdoctoral Fellow, Aix-Marseille School of Economics EDUCATION 2007 – 2012 PhD in Economics, Stockholm University (visiting the University of Toronto for the 2010 – 2011 academic year) 2005 – 2007 MA in Economics, Michigan State University 2002 – 2003 MCom, University of New South Wales 1998 – 2000 BCom, University of Melbourne PUBLICATIONS “Airport size and urban growth”, Economica, forthcoming. “Airport consolidation and the provision of air services”, Journal of Air Transport Management, May 2017, Vol. 60, pp. 31–44. “Learning to export and the timing of entry to export markets”, Review of International Economics, August 2014, Vol. 22 (3), pp. 536–560. “Airports and urban sectoral employment”, Journal of Urban Economics, March 2014, Vol. 80, pp. 133–152. “Regional policy in a multiregional setting: when the poorest are hurt by subsidies”, Review of World Economics, June 2012, Vol. 148 (2), pp. 403–423. WORKING PAPERS “Airport infrastructure and national employment: evidence from the US” “Life-cycle -

Annual Report 2020

OVERVIEW ANNUAL REPORT 2020 ANNUAL REPORT 2020 1 2 ANNUAL REPORT 2020 OVERVIEW CONTENTS OVERVIEW ENVIRONMENTAL PERFORMANCE Letter to the Minister for Training and Skills 1 Introduction and scope 81 Vice-Chancellor’s statement 2 Commitments, governance and resources 82 Report of members of Monash University Council 5 Staff resources 84 Meetings of members 8 Staff and student engagement 87 Organisational charts 10 Energy consumption 91 Water consumption 93 CORE BUSINESS: EDUCATION, RESEARCH, Waste 94 GLOBAL ENGAGEMENT Sustainable transport 95 Key initiatives and projects 15 Procurement 96 Research and education: Paper 97 Office of the Provost and Senior Vice-President 22 The built environment and landscape 98 Education 27 Global engagement 30 FINANCIAL PERFORMANCE Enterprise 35 Disclosure index 109 Report of the President, Academic Board 39 Statements 115 Statements of compliance 42 Notes 121 Website address for current Declaration 188 and previous annual reports 48 SOCIAL PERFORMANCE Monash people 50 Staff engagement and employment conduct 51 Student profile 55 Student experience 57 Health, safety, wellbeing and family 64 Equity, access and diversity— students and staff 71 Social responsibility 77 ANNUAL REPORT 2020 OVERVIEW OVERVIEW ANNUAL REPORT 2020 OVERVIEW Dear Minister, LETTER TO THE MINISTER In accordance with the requirements and regulations under the Financial Management Act 1994, I submit for FOR TRAINING AND SKILLS tabling in the Victorian Parliament the Annual Report of Monash University for the year ending 31 December 2020. The Hon. Gayle Tierney MP Minister for Training and Skills and Minister for This Report was approved by the Monash University Higher Education Council on 24 March 2021. -

Monash Energy Profile 2020

MONASH ENERGY INSTITUTE MONASH ENERGY PROFILE 2020 monash.edu/energy-institute 2020 is a year like no other in recent history. CONTENTS Over the summer, bushfires engulfed many parts of Australia, only to be followed by COVID-19. On the one hand, the bushfires filled our skies with smoke, causing the air quality to reach unprecedented poor quality, while also mass releasing CO2 from the burning of over 12.6 million hectares of bushland. The fire- affected areas concurrently experienced major electricity blackouts and reliability issues, requiring the use 1 Welcome of expensive backup power to provide essential services. Meanwhile, the confinement of people at home during COVID-19 saw the empty streets in most global cities result in pollution levels plummeting, yielding 3 About us blue skies and fresh air in many countries for the first time in years. Concurrently, the average household energy usage spiked causing major concerns about ongoing energy affordability, while oil markets 4 Our leadership team crashed due to geopolitical conflict to provide the cheapest petrol prices in over a decade. 6 Initiatives At face value, this scenario is chaotic. It presents a series of events that could not have been readily predicted. Nonetheless, it provides a timely reminder of the intrinsic volatility that people are exposed to 12 Research during major world crises. In such events, access to energy, whether it is in the form of electricity or a fuel, is an essential service to ensure the wellbeing of our people and continuing operation of our businesses, 20 ARC Centres transport and industry sectors. -

(Jae Eun) Choi

Jen (Jae Eun) Choi PhD Candidate in Accounting [email protected] EDUCATION Emory University, Atlanta, GA 2022 (Expected) Ph.D. in Accounting Seoul National University, Seoul, Korea 2017 Master of Science in Accounting Korea University, Seoul, Korea 2015 Bachelor of Business Administration and Financial Engineering, Summa Cum Laude ESADE, Barcelona, Spain 2013 Korea University exchange student program PROFESSIONAL INTERESTS Research: Management Control Systems, Executive Compensation, and Supply Chain Relationships Teaching: Managerial/Financial Accounting, Data Analytics RESEARCH (*: Presenter, c: Coauthor presentation) [1] Choi, J. (2021) Sales-based CEO Incentive and Its Effect across the Supply Chain (Dissertation) ▪ Committee: Karen Sedatole, Mary Ellen Carter, Ilia Dichev, Kristy Towry, and Gonzalo Maturana ▪ Presented at Emory University* [2] Carter, M., Choi, J., Sedatole, K. (2021) The Effect of Supplier Industry Competition on Pay-for- Performance Incentive Intensity. Status: Published at Journal of Accounting and Economics, 71(2-3), 101389 ▪ Presented at Clemson Universityc, 2020 FARS Research Roundtables*, George Mason Universityc, 2019 GMARS* (Michigan State University), 2019 GRACE* (Emory University), INSEADc, 2018 Notre Dame Accounting Research Conferencec, 2019 MAS Meeting*, Monash Universityc, Temple Universityc, and University of Washingtonc [3] Carter, M., Choi, J., Sedatole, K. (2021) Customer RPE: Using Customer Performance to Filter Noise Out of CEO Incentive Contracts ▪ Developed from second-year summer paper at Emory University ▪ Received funding from the IMA Doctoral Scholars Program ▪ Presented at 2020 AAA Annual Meeting*, Arizona State Universityc, 2021 CAAA Annual Meeting*, Executive Compensation Corporate Governance Brownbag Seriesc, 2021 FARS Meeting*, Harvard Business Schoolc, KAIST Business School*, 2021 MAS Meeting*, University of Nebraska-Lincolnc, and 2021 EIASM* [4] Choi, J., Forker, E., Grabner, I., Sedatole, K.