Heaven: the Logic of Eternal Joy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Songs by Title

Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist #1 Goldfrapp (Medley) Can't Help Falling Elvis Presley John Legend In Love Nelly (Medley) It's Now Or Never Elvis Presley Pharrell Ft Kanye West (Medley) One Night Elvis Presley Skye Sweetnam (Medley) Rock & Roll Mike Denver Skye Sweetnam Christmas Tinchy Stryder Ft N Dubz (Medley) Such A Night Elvis Presley #1 Crush Garbage (Medley) Surrender Elvis Presley #1 Enemy Chipmunks Ft Daisy Dares (Medley) Suspicion Elvis Presley You (Medley) Teddy Bear Elvis Presley Daisy Dares You & (Olivia) Lost And Turned Whispers Chipmunk Out #1 Spot (TH) Ludacris (You Gotta) Fight For Your Richard Cheese #9 Dream John Lennon Right (To Party) & All That Jazz Catherine Zeta Jones +1 (Workout Mix) Martin Solveig & Sam White & Get Away Esquires 007 (Shanty Town) Desmond Dekker & I Ciara 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z Ft Beyonce & I Am Telling You Im Not Jennifer Hudson Going 1 3 Dog Night & I Love Her Beatles Backstreet Boys & I Love You So Elvis Presley Chorus Line Hirley Bassey Creed Perry Como Faith Hill & If I Had Teddy Pendergrass HearSay & It Stoned Me Van Morrison Mary J Blige Ft U2 & Our Feelings Babyface Metallica & She Said Lucas Prata Tammy Wynette Ft George Jones & She Was Talking Heads Tyrese & So It Goes Billy Joel U2 & Still Reba McEntire U2 Ft Mary J Blige & The Angels Sing Barry Manilow 1 & 1 Robert Miles & The Beat Goes On Whispers 1 000 Times A Day Patty Loveless & The Cradle Will Rock Van Halen 1 2 I Love You Clay Walker & The Crowd Goes Wild Mark Wills 1 2 Step Ciara Ft Missy Elliott & The Grass Wont Pay -

The-Desire-Of-Ages.Pdf

The Desire of Ages Ellen G. White 1898 Copyright © 2011 Ellen G. White Estate, Inc. Information about this Book Overview This eBook is provided by the Ellen G. White Estate. It is included in the larger free Online Books collection on the Ellen G. White Estate Web site. About the Author Ellen G. White (1827-1915) is considered the most widely translated American author, her works having been published in more than 160 languages. She wrote more than 100,000 pages on a wide variety of spiritual and practical topics. Guided by the Holy Spirit, she exalted Jesus and pointed to the Scriptures as the basis of one’s faith. Further Links A Brief Biography of Ellen G. White About the Ellen G. White Estate End User License Agreement The viewing, printing or downloading of this book grants you only a limited, nonexclusive and nontransferable license for use solely by you for your own personal use. This license does not permit republication, distribution, assignment, sublicense, sale, preparation of derivative works, or other use. Any unauthorized use of this book terminates the license granted hereby. Further Information For more information about the author, publishers, or how you can support this service, please contact the Ellen G. White Estate at [email protected]. We are thankful for your interest and feedback and wish you God’s blessing as you read. i ii Preface In the hearts of all mankind, of whatever race or station in life, there are inexpressible longings for something they do not now possess. This longing is implanted in the very constitution of man by a merciful God, that man may not be satisfied with his present conditions or attainments, whether bad, or good, or better. -

Celebrate 150 YEARS of ARTISTIC SPIRIT Thank You the Richmond Hill Centre for the Performing Arts Gratefully Acknowledges the Generous Contribution of Our Sponsors

RICHMOND HILL CENTRE FOR THE PERFORMING ARTS 2016/2017I seasonSEASON Season Sponsor celebrate 150 YEARS of ARTISTIC SPIRIT Thank You The Richmond Hill Centre for the Performing Arts gratefully acknowledges the generous contribution of our sponsors. Season Sponsor Series Sponsors Official Supplier of Musical Instruments Official Hotel Sponsor Theatre Sponsors Official RHCPA Photographer Show Sponsors Uncomplicate your I.T. 2 Table of Contents Visit page 46 and 47 for Pricing and Packages. 4 Messages 25 Theatre Seating Plan 6 ON! Stage Series 26 This is That 7 Theatre Rental 27 Los Lobos 8 Theatre Programs 28 The Tea Party 9 Opening Night: Our Town, Our Talent 29 C.A.L.: Wish You Were Here 10 80’s House Party 30 Pete the Cat 11 The Lightning Thief 31 Whitehorse 12 Save the Date! 32 International Women’s Day Celebration 13 Brent Butt 33 C.A.L.: Joshua Tree 14 Tokyo Police Club 34 Terri Clark 15 Peter Rabbit 35 C.A.L.: White Album 16 C.A.L.: Last Waltz 36 Seussical 17 Zero Gravity Circus 37 The Honouring Kaha:wi Dance Theatre 18 Wingfield’s Inferno 38 Backstage Pass 19 Toopy & Binoo: Fun & Games 39 Sharon and Bram 20 A Leahy Family Christmas 40 Cecilia String Quartet 21 The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe 41 Patron Services and Information 22 Christmas Celebration 42 Education Series 23 Comedy & Cabaret New Year’s Eve 43 Community Presents Club RHCPA Prices and Packages 24 46 RHCPA Location: 10268 Yonge Street, Richmond Hill, Ontario, Canada L4C 3B7 The theatre is located three lights north of Major Mackenzie Drive, on the west side of Yonge Street. -

Fifty Short Sermons by T

FIFTY SHORT SERMONS BY T. De WITT TALMAGE COMPILED BY HIS DAUGHTER MAY TALMAGE NEW ^SP YORK GEORGE H. DORAN COMPANY TUB NBW YO«K PUBUC LIBRARY O t. COPYRIGHT, 1923, BY GEORGE H. DORAN COMPANY 1EW YO:;iC rUbLiC LIBRMIY ASTOR, LENOX AND TILDEN FOUNDATIONS R 1025 L FIFTY SHORT SERMONS BY T. DE WITT TALMAGE. II PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA y CONTENTS I The Three Crosses II Twelve Entrances . III Jordanic Passage . IV The Coming Sermon V Cloaks for Sin /VI The Echoes . VII A Dart through the Liver VIII The Monarch of Books . JX The World Versus the Soul ^ X The Divine Surgeon XI Music in Worship . XII A Tale Told, or, The Passing Years XIII What Were You Made For? XIV Pulpit and Press . XV Hard Rowing . XVI NoontiGe of Life . XVII Scroll oi Heroes XVIII Is Life Worth Living? , XIX Grandmothers , ,. j.,^' XX The Capstoii^''''' '?'*'''' XXI On Trial .... XXII Good Qame Wasted XXIII The Sensitiveness of Christ XXIV Arousing Considerations Ti CONTENTS PAGE XXV The Threefold Glory of the Church . 155 XXVI Living Life Over Again 160 XXVII Meanness of Infidelity 163 XXVIII Magnetism of Christ 168 XXIX The Hornet's Mission 176 XXX Spicery of Religion 182 XXXI The House on the Hills 188 XXXII A Dead Lion 191 XXXIII The Number Seven 196 XXXIV Distribution of Spoils 203 XXXV The Sundial of Ahaz 206 XXXVI The Wonders of the Hand . .210 XXXVII The Spirit of Encouragement . .218 XXXVIII The Ballot-Box 223 XXXIX Do Nations Die? 229 XL The Lame Take the Prey . -

Here Without You 3 Doors Down

Links 22 Jacks - On My Way 3 Doors Down - Here without You 3 Doors Down - Kryptonite 3 Doors Down - When I m Gone 30 Seconds to Mars - City of Angels - Intermediate 30 Seconds to Mars - Closer to the edge - 16tel und 8tel Beat 30 Seconds To Mars - From Yesterday https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RpG7FzXrNSs 30 Seconds To Mars - Kings and Queens 30 Seconds To Mars - The Kill 311 - Beautiful Disaster - - Intermediate 311 - Dont Stay Home 311 - Guns - Beat ternär - Intermediate 38 Special - Hold On Loosely 4 Non Blondes - Whats Up 44 - When Your Heart Stops Beating 9-8tel Nine funk Play Along A Ha - Take On Me A Perfect Circle - Judith - 6-8tel 16tel Beat https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xTgKRCXybSM A Perfect Circle - The Outsider ABBA - Knowing Me Knowing You ABBA - Mamma Mia - 8tel Beat Beginner ABBA - Super Trouper ABBA - Thank you for the music - 8tel Beat 13 ABBA - Voulez Vous Absolutum Blues - Coverdale and Page ACDC - Back in black ACDC - Big Balls ACDC - Big Gun ACDC - Black Ice ACDC - C.O.D. ACDC - Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap ACDC - Evil Walks ACDC - For Those About To Rock ACDC - Givin' The Dog A Bone ACDC - Go Down ACDC - Hard as a rock ACDC - Have A Drink On Me ACDC - Hells Bells https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qFJFonWfBBM ACDC - Highway To Hell ACDC - I Put The Finger On You ACDC - It's A Long Way To The Top ACDC - Let's Get It Up ACDC - Money Made ACDC - Rock n' Roll Ain't Noise Pollution ACDC - Rock' n Roll Train ACDC - Shake Your Foundations ACDC - Shoot To Thrill ACDC - Shot Down in Flames ACDC - Stiff Upper Lip ACDC - The -

Out There in the Dark There's a Beckoning Candle: Stories

OUT THERE IN THE DARK THERE’S A BECKONING CANDLE: STORIES By © Benjamin C. Dugdale, a creative writing thesis submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in partial fulfillment for the degree of Master of Arts in English Memorial University of Newfoundland April 2021 St. John’s, Newfoundland & Labrador. Abstract (200 words) OUT THERE IN THE DARK THERE’S A BECKONING CANDLE is a collection of interrelated short stories drawing from various generic influences, chiefly ‘weird,’ ‘gothic,’ ‘queer’ and ‘rural’ fiction. The collection showcases a variety of recurring characters and settings, though from one tale to the next, discrepancies, inversions, and a whelming barrage of transforming motifs force an unhomely displacement between each story, troubling reader assumptions about the various protagonists to envision a lusher plurality of possible selves and futures (a gesture towards queer spectrality, which Carla Freccero defines as the “no longer” and the “not yet”). Utilizing genres known for their unsettling and fantastical potency, the thesis constellates the complex questions of identity politics, toxic interpersonal-relationships, the brutality of capitalism, compulsory urban migration, rituals of grief, intergenerational transmission of trauma, &c., all through a corrupted mal-refracting queer prism; for example, the simple question of what discomfort recurring character Harlanne Welch, non-binary filmmaker, sees when they look into the mirror is demonstrative, when the thing in the mirror takes on its own life with far-reaching consequences. OUT THERE IN THE DARK…is an oneiric, ludic dowsing rod in pursuit of the queer prairie gothic mode just past line of sight on the horizon. ii General Summary. -

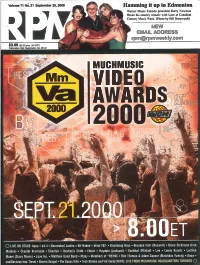

Hamming It up in Edmonton NEW EMAIL ADDRESS Rpm@Rpmweekly

Volume 71 No. 21 September 25, 2000 Hamming it up in Edmonton Warner Music Canada president Garry Newman flexes his country muscle with Lace at Canadian Country Music Week. (Photo by Bill Borgwardt) NEW EMAIL ADDRESS [email protected] $3.00 ($2.80 plus .20 GST) Publication Mail Re istration No. 08141 0 LIVE ON STAGE: Aqua • b4-4 • Barenaked Ladies • Bif Naked • blink-182- • Boomtang Boys • Brendan Fehr (Roswell) • Bruce Dickinson (Iron Maiden) • Chantal Kreviazuk • Choclair • Destiny's Child • Edwin • Haydain (jacksoul) • Kardinal Offishall • Len • Lenny Kravitz • Lochlyn Munro (Scary Movie) • Love Inc. • Matthew Good Band • Moby • Members of *NSYNC • Rob Thomas &Adam Gaynor (Matchbox Twenty) • Snow • soulDecision feat.Thrust • Steven Seagal • The Guess Who • Irish Stratus and Val Venis (WWF). LIVE FROM MUCHMUSIC HEADQUARTERS TORONTO CONGRATULATIONS TO OUR MMVA NOMINEES ACKSOU CAI é IUNDERSTA BE VIDEO TOP OF THE WO HER OMES THE SUNSHINE BEST RAP VIDEO BEST DANCE VIDEO BEST POST-PRODUCTION LA VIE TI NEG BEST FRENCH VIDEO BEST INTERNATIONAL VIDEO . , . THAN LIFE PEOPLE'S CHOICE- FAVOURITE INTERNATIONAL GROUP OOPS...I DID IT AGAIN BEST INTERNATIONAL VIDEO PEOPLE'S CHOICE-FAVOURITE INTERNATIONAL VIDEO NATURAL BLUES BEST INTERNATIONAL VIDEO 410k BYE HRISTINA AGUILER BEST INTERNATIONAL VIDEO GENIE IN ABOTTLE PEOPLE'S CHOICE- FAVOURITE INTERNATIONAL GROUP FAVOURITE INTERNATIONAL ARTIST THANKS TO RPM - Monday September 25, 2UUU - Release, Psychopomp, Heaven Coming Down, The Tea Party to release best-of album in November Messenger, Waiting On A Sign (download track After 17 months of touring, and encircling the world This past summer, lead vocalist Jeff Martin was from TRIPtych sessions), Paint It Black (cover of three times, EMI Music Canada's The Tea Party are in Ireland producing anew album for veteran English Rolling Stones classic, recorded during TRIPtych currently in the studio, putting the final touches on folk singer Roy Harper. -

Title of Record

Now MusiquePlus and MUchMusic radio, Rock at Impacting Fold" The To "Welcome Video, and Single First The 8/24/99 Stores In a . from CD Epic Gargantuan, Bombastic; New The \I E _.... ix Record of Title fl ir At- 0 08141 No. Registration Mail Publication 4 GST) .20 plus ($2.80 $3.00 4 * * 23, August 18- No. 69 Volume a I * * * a * I 0 # * 4111 4 fett. * - I * I 0 0 * I I * I 0,0 * (%; 100 HITTRACKS ir Roger Ames to chair Roger Ames, who has been a member Et where to find them management team of Warner Music since April of this year, has been nan Record Distributor Codes: Canada's Only National 100 Hit Tracks Survey and chief executive officer of Warner BMG - N EMI - F Universal - J which relocates its corporate operations. indicates biggest mover Polygram - co Sony - H Warner - P oft- City. TW LW WO AUGUST 23, 1999 The above announcement was n 1 1 11 IF YOU HAD MY LOVE 35 32 2 SHE'S ALL I EVER HAD 68 58 31 EVERY MORNING Toronto's KISS 92 zi Jennifer Lopez - On The 6 Ricky Martin - Ricky Martin Sugar Ray - 14:59 Work 69351 (pro single) - P C2/Columbia 69891 (pro single) - H Atlantic 83151 (promo CD) - P It's only the middle of August, but R 5 12 ALL STAR 36 31 4 SMILE 69 67 14 ALMOST DOESN'T COUNT Backstreet Boys, November 11 is alrea Smash Mouth - Astro Lounge Vitamin C - Self Titled Brandy - Never Say Never Interscope 6601 (pro single) - J Elektra 62406 (comp 405) - P Atlantic 63039 (CD Track) - P the calendar and on their mind. -

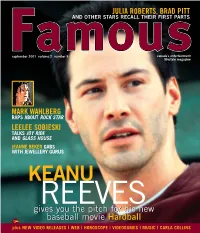

Hardballhardball Plus NEW VIDEO RELEASES | WEB | HOROSCOPE | VIDEOGAMES | MUSIC | CARLA COLLINS Contents Famous | Volume 2 | Number 9 |

JULIA ROBERTS, BRAD PITT AND OTHER STARS RECALL THEIR FIRST PARTS september 2001 volume 2 number 9 canada’s entertainment lifestyle magazine MARK WAHLBERG RAPS ABOUT ROCK STAR LEELEE SOBIESKI TALKS JOY RIDE AND GLASS HOUSE JEANNE BEKER GABS WITH JEWELLERY GURUS KEANU REEVES givesgives youyou thethe pitchpitch forfor hishis newnew $300 baseballbaseball moviemovie HardballHardball plus NEW VIDEO RELEASES | WEB | HOROSCOPE | VIDEOGAMES | MUSIC | CARLA COLLINS contents Famous | volume 2 | number 9 | 28 20 18 FEATURES COLUMNS 20 MARKY MARK AND THE METALHEADS 10 HEARSAY Perhaps it’s because he didn’t get to Carla Collins on Will Smith’s heroic act play a monkey in Planet of the Apes that Mark Wahlberg jumped at the 38 LINER NOTES chance to don a long, flowing mane DEPARTMENTS Tea Party’s singer talks for the heavy metal comedy Rock Star. Find out how he felt about that fake 06 EDITORIAL 40 BIT STREAMING lid and why it wasn’t easy for this The web’s grave situation former pop star to play a rocker 09 LETTERS By Earl Dittman 41 NAME OF THE GAME 12 SHORTS Your DVDs are hiding something 26 GO EAST Canada goes film fest crazy How did a New York dancer and a model from Vancouver end up making 16 THE BIG PICTURE jewellery for some of Hollywood’s Heist, Big Trouble and Zoolander open biggest stars? Jeanne Beker takes a across the country look at the Eastern-inspired finery of New York’s hot design team Me & Ro 18 THE PLAYERS What’s the story with Milla Jovovich, 28 THREE FOR LEELEE Janeane Garofalo and Ethan Hawke? If Leelee Sobieski’s distinctive name doesn’t distinguish her from the pack, 30 COMING SOON the three films she stars in this fall should. -

CHRESTO MATHY the Poetry Issue

CHRESTO MATHY Chrestomathy (from the Greek words krestos, useful, and mathein, to know) is a collection of choice literary passages. In the study of literature, it is a type of reader or anthology that presents a sequence of example texts, selected to demonstrate the development of language or literary style The Poetry Issue TOYIA OJiH ODUTOLA WRITING FROM THE SEVENTH GRADE, 2019-2020 THE CALHOUN MIDDLE SCHOOL 1 SADIE HAWKINS Fairy Tale Poem I Am Poem Curses are fickle. You may have heard the story, I am loyal and trusting. Sleeping Beauty, I wonder what next and what now? The royal family births a child I hear songs that aren’t played, An event like this is to be remembered in joy by I see a world beyond ours, all. I want to travel. Yet it was spoiled, I am loyal and trusting, Why, you ask? I pretend to be part of the books I read. The parents, out of fear, made a fatal mistake. I feel happy and sad, They left out one guest. I touch soft fluff. One of the fairies of the forest, I worry about the future, The other three came, all but one. I cry over those lost. When it came for this time for the gifts it I am loyal and trusting happened. I understand things change, This is the story of Maleficent. I say they get better. This is my story. I dream for a better world, I try to understand those around me. It had come, I hope that things will improve, The birth of the heir I am loyal and trusting. -

The Youth's Instructor for 1934

Vol. 82 January 23, 1934 No. 4 C. !.,?zpi ...,, •,,..,4-?..qN,,44 t,:' -3V:11,rfro;'4V5*Z1v-.;rt-e-.4 .M?. , t,, , - =_—J1 r LI 1111111111111111111111//1111111/1.111111111111111111111111111111111111111111/11111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111/1110.1.11111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111110111i 111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111X1111111111111111111111111 111111111111111111111111111111111111111011111111111111111111111. There ig a little recipe to mix Witt) pour 7 1- bailp toil to make life abounb tuitlj contentment: •gZ-_-> Tefie inbugtriout: life gibeg nothing tuitijout labor. <=> Tge brabe: fortitube it a galbe for bigtregg. Tge frienblp: cherigh companion= tbip. .0--> Tge forgibing: "go err is but human; to forgibe, bibine." e bonegt: it papg. r-> je tljriftp: for tbote Wbo bepenb on pou, if not for pourgelf. .4@:%. Tge ungelfigb: bo anp Boob pou can nob), for pou Will not page tbig tuap again. Ti3e compaggion= ate: the bust pou treab on Wag once alike. jOe moberate: it ig best. ji3e unberttanbing anb gpmpatbetic: pou Will be fair. 'gE --> Tge optimigtic: took on tije brigbt gibe, but bon't bepenb on luck. >4@:>. loge no time: remember, tbe bout. Ibbich gate pou life began to take it wimp.‹r.->- 31n otber Worbt, lice 5o that tuljen tbe time for parting comes pou Will not ibbigper, "Vilbat a fool 3'be been."—Isabel Manchester. VE shall be witnesses unto Me of every organization and institution enth-day Adventist. I made up my 1 both in Jerusalem, and in all with which he is connected. A boy mind I would ask you and find out Judea, and in Samaria, and unto the represents his home and parents, his for sure." uttermost part of the earth." friends, his school and Sabbath And then as Margaret listened, a Jesus is speaking. -

Another Sign in Heaven Revealing the Wrath of God

Third Exodus Assembly The Revelation Of The Seven Vials Another Sign In Heaven Revealing The Wrath Of God 23rd September 1984 Third Exodus Assembly The Revelation Of The Seven Vials ANOTHER SIGN IN HEAVEN REVEALING THE WRATH OF GOD 23rd September 1984 TRINIDAD Bro. Vin A. Dayal THE REVELATION OF THE SEVEN VIALS Another Sign In Heaven Revealing The Wrath Of God TRINIDAD SUNDAY 23rd SEPTEMBER 1984 BRO. VIN A. DAYAL Oh, let everybody sing that now. [# 478, Songs That Live. –Ed.] Let the Church be the Church, Let the people rejoice, Let the people rejoice, For we’ve settled the question, We’ve... Oh, we’ve made our choice this morning; we’ll take the way with the Lord’s despised few. Let the anthems ring out, Songs of victory swell, For the Church triumphant Is alive and well. Oh, for the last time now, everyone singing, all in that Church, in that Body. Let the Church be the Church, Let the people rejoice, For we’ve settled the question, If God be God, serve God. Oh, we’ve made our choice. We are on the Lord’s side. Let the anthems ring out, Let it go right up into Heaven. Songs of victory swell, For the Church triumphant Is alive... Let Satan know it. Is alive and well. 1 Another Sign In Heaven Revealing The Wrath Of God 1984-0923 One more time. Let the devil know the Church is alive; let him know he cannot destroy this Church, he is powerless before this Great Army. For we’ve settled the question, We’ve made a total separation from unbelief.