In the Matrix: Eutopian Mapping in a Posthuman World

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Digital Dialectics: the Paradox of Cinema in a Studio Without Walls', Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television , Vol

Scott McQuire, ‘Digital dialectics: the paradox of cinema in a studio without walls', Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television , vol. 19, no. 3 (1999), pp. 379 – 397. This is an electronic, pre-publication version of an article published in Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television. Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television is available online at http://www.informaworld.com/smpp/title~content=g713423963~db=all. Digital dialectics: the paradox of cinema in a studio without walls Scott McQuire There’s a scene in Forrest Gump (Robert Zemeckis, Paramount Pictures; USA, 1994) which encapsulates the novel potential of the digital threshold. The scene itself is nothing spectacular. It involves neither exploding spaceships, marauding dinosaurs, nor even the apocalyptic destruction of a postmodern cityscape. Rather, it depends entirely on what has been made invisible within the image. The scene, in which actor Gary Sinise is shown in hospital after having his legs blown off in battle, is noteworthy partly because of the way that director Robert Zemeckis handles it. Sinise has been clearly established as a full-bodied character in earlier scenes. When we first see him in hospital, he is seated on a bed with the stumps of his legs resting at its edge. The assumption made by most spectators, whether consciously or unconsciously, is that the shot is tricked up; that Sinise’s legs are hidden beneath the bed, concealed by a hole cut through the mattress. This would follow a long line of film practice in faking amputations, inaugurated by the famous stop-motion beheading in the Edison Company’s Death of Mary Queen of Scots (aka The Execution of Mary Stuart, Thomas A. -

The Matrix As an Introduction to Mathematics

St. John Fisher College Fisher Digital Publications Mathematical and Computing Sciences Faculty/Staff Publications Mathematical and Computing Sciences 2012 What's in a Name? The Matrix as an Introduction to Mathematics Kris H. Green St. John Fisher College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://fisherpub.sjfc.edu/math_facpub Part of the Mathematics Commons How has open access to Fisher Digital Publications benefited ou?y Publication Information Green, Kris H. (2012). "What's in a Name? The Matrix as an Introduction to Mathematics." Mathematics in Popular Culture: Essays on Appearances in Film, Fiction, Games, Television and Other Media , 44-54. Please note that the Publication Information provides general citation information and may not be appropriate for your discipline. To receive help in creating a citation based on your discipline, please visit http://libguides.sjfc.edu/citations. This document is posted at https://fisherpub.sjfc.edu/math_facpub/18 and is brought to you for free and open access by Fisher Digital Publications at St. John Fisher College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. What's in a Name? The Matrix as an Introduction to Mathematics Abstract In my classes on the nature of scientific thought, I have often used the movie The Matrix (1999) to illustrate how evidence shapes the reality we perceive (or think we perceive). As a mathematician and self-confessed science fiction fan, I usually field questionselated r to the movie whenever the subject of linear algebra arises, since this field is the study of matrices and their properties. So it is natural to ask, why does the movie title reference a mathematical object? Of course, there are many possible explanations for this, each of which probably contributed a little to the naming decision. -

System Safety Engineering: Back to the Future

System Safety Engineering: Back To The Future Nancy G. Leveson Aeronautics and Astronautics Massachusetts Institute of Technology c Copyright by the author June 2002. All rights reserved. Copying without fee is permitted provided that the copies are not made or distributed for direct commercial advantage and provided that credit to the source is given. Abstracting with credit is permitted. i We pretend that technology, our technology, is something of a life force, a will, and a thrust of its own, on which we can blame all, with which we can explain all, and in the end by means of which we can excuse ourselves. — T. Cuyler Young ManinNature DEDICATION: To all the great engineers who taught me system safety engineering, particularly Grady Lee who believed in me, and to C.O. Miller who started us all down this path. Also to Jens Rasmussen, whose pioneering work in Europe on applying systems thinking to engineering for safety, in parallel with the system safety movement in the United States, started a revolution. ACKNOWLEDGEMENT: The research that resulted in this book was partially supported by research grants from the NSF ITR program, the NASA Ames Design For Safety (Engineering for Complex Systems) program, the NASA Human-Centered Computing, and the NASA Langley System Archi- tecture Program (Dave Eckhart). program. Preface I began my adventure in system safety after completing graduate studies in computer science and joining the faculty of a computer science department. In the first week at my new job, I received a call from Marion Moon, a system safety engineer at what was then Ground Systems Division of Hughes Aircraft Company. -

Christianity, Buddhism & Baudrillard in the Matrix Films and Popular Culture

Butler University Digital Commons @ Butler University Scholarship and Professional Work - LAS College of Liberal Arts & Sciences 2010 The Desert of the Real: Christianity, Buddhism & Baudrillard in The Matrix Films and Popular Culture James F. McGrath Butler University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/facsch_papers Part of the Philosophy Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation James F. McGrath. "The Desert of the Real: Christianity, Buddhism & Baudrillard in The Matrix Films and Popular Culture" Visions of the Human in Science Fiction and Cyberpunk. Ed. Marcus Leaning & Birgit Pretzsch. Oxford, UK: Inter-Disciplinary Press, 2010. 161-172. Available from: digitalcommons.butler.edu/ facsch_papers/556/ This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Liberal Arts & Sciences at Digital Commons @ Butler University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Scholarship and Professional Work - LAS by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Butler University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Edited by Marcus Leaning & Birgit Pretzsch The Desert of the Real: Christianity, Buddhism & Baudrillard in The Matrix Films and Popular Culture James F. McGrath Abstract The movie The Matrix and its sequels draw explicitly on imagery from a number of sources, including in particular Buddhism, Christianity, and the writings of Jean Baudrillard. A perspective is offered on the perennial philosophical question ‘What is real?’, using language and symbols drawn from three seemingly incompatible world views. In doing so, these movies provide us with an insight into the way popular culture makes eclectic use of various streams of thought to fashion a new reality that is not unrelated to, and yet is nonetheless distinct from, its religious and philosophical undercurrents and underpinnings. -

Imagining a Multiracial Future Author(S): Leilani Nishime Source: Cinema Journal, Vol

Society for Cinema & Media Studies The Mulatto Cyborg: Imagining a Multiracial Future Author(s): LeiLani Nishime Source: Cinema Journal, Vol. 44, No. 2 (Winter, 2005), pp. 34-49 Published by: University of Texas Press on behalf of the Society for Cinema & Media Studies Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3661093 Accessed: 18-09-2016 02:53 UTC REFERENCES Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3661093?seq=1&cid=pdf-reference#references_tab_contents You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms Society for Cinema & Media Studies, University of Texas Press are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Cinema Journal This content downloaded from 128.210.126.199 on Sun, 18 Sep 2016 02:53:57 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms The Mulatto Cyborg: Imagining a Multiracial Future by LeiLani Nishime Abstract: Applying the literature of passing to cyborg cinema makes visible the politics of cyborg representations and illuminates contemporary conceptions of mixed-race subjectivity and interpolations of mixed-race bodies. The passing nar- rative also reveals the constitutive role of melancholy and nostalgia both in creat- ing cyborg cinema and in undermining its subversive potential. -

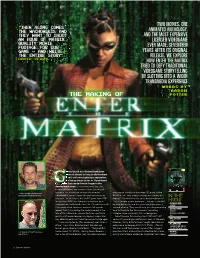

The Making of Enter the Matrix

TWO MOVIES. ONE “THEN ALONG COMES THE WACHOWSKIS AND ANIMATED ANTHOLOGY. THEY WANT TO SHOOT AND THE MOST EXPENSIVE AN HOUR OF MATRIX LICENSED VIDEOGAME QUALITY MOVIE FOOTAGE FOR OUR EVER MADE. SEVENTEEN GAME – AND WRITE YEARS AFTER ITS ORIGINAL THE ENTIRE STORY” RELEASE, WE EXPLORE DAVID PERRY HOW ENTER THE MATRIX TRIED TO DEFY TRADITIONAL VIDEOGAME STORYTELLING BY SLOTTING INTO A WIDER TRANSMEDIA EXPERIENCE Words by Aaron THE MAKING OF Potter ames based on a licence have been around almost as long as the medium itself, with most gaining a reputation for being cheap tie-ins or ill-produced cash grabs that needed much longer in the development oven. It’s an unfortunate fact that, in most instances, the creative teams tasked with » Shiny Entertainment founder and making a fun, interactive version of a beloved working on a really cutting-edge 3D game called former game director David Perry. Hollywood IP weren’t given the time necessary to Sacrifice, so I very embarrassingly passed on the IN THE succeed – to the extent that the ET game from 1982 project.” David chalks this up as being high on his for the Atari 2600 was famously rushed out by a “list of terrible career decisions”, though it wouldn’t KNOW single person and helped cause the US industry crash. be long before he and his team would be given a PUBLISHER: ATARI After every crash, however, comes a full system second chance. They could even use this pioneering DEVELOPER : reboot. And it was during the world’s reboot at the tech to translate the Wachowskis’ sprawling SHINY turn of the millennium, around the time a particular universe more accurately into a videogame. -

Back to the Future: the Implications of Service and Problem-Based Learning in the Language, Literacy, and Cultural Acquisition of ESOL Students in the 21St Century

The Reading Matrix: An International Online Journal Volume 18, Number 2, September 2018 Back to the future: The implications of service and problem-based learning in the language, literacy, and cultural acquisition of ESOL students in the 21st century Margaret Aker Concordia University, Chicago Luis Javier Pentón Herrera University of Maryland, Baltimore County (UMBC) Lynn Daniel Concordia University, Chicago ABSTRACT Research has identified the essential proficiencies students should possess to be successful, but they are often not incorporated in the ESOL classroom. As a result, many teachers lack access to adequate instructional strategies to guide ELs to academic success. We argue in this article that, to provide a strong foundation and a bright future for ESOL students, problem-based learning and service-learning (PBSL) should be combined to activate the skills identified by the Partnership for 21st Century Skills (2011). For this, we reflect on the 21st century skills and the implications for teaching today’s students—the Millennials and GenZs—keeping in mind the professionals they will become tomorrow. Reflecting a student-centered approach, we incorporate practice into the research process by illustrating a successful integration of PBSL into an ESOL learning environment in higher education and then highlight additional curricular opportunities for synthesizing PBSL at the elementary, middle, and high school levels. INTRODUCTION “Education is for improving the lives of others and for leaving your community and world better than you found it” (Edelman, 1993, pp. 9-10). Inspired by a call for research in the Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages (TESOL) field (Wurr, 2013), we seek to contribute by proposing a model that guides the larger discourse on service-learning, civic engagement, and language learning for minority students. -

'The Coolest Way to Watch Movie Trailers in the World': Trailers in the Digital Age Keith M. Johnston

1 This is an Author's Accepted Manuscript of an article published in Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies 14, 2 (2008): 145- 60, (c) Sage Publications Available online at: http://con.sagepub.com/content/14/2/145.full.pdf+html DOI: 10.1177/1354856507087946 ‘The Coolest Way to Watch Movie Trailers in the World’: Trailers in the Digital Age Keith M. Johnston Abstract At a time of uncertainty over film and television texts being transferred online and onto portable media players, this article examines one of the few visual texts that exists comfortably on multiple screen technologies: the trailer. Adopted as an early cross-media text, the trailer now sits across cinema, television, home video, the Internet, games consoles, mobile phones and iPods. Exploring the aesthetic and structural changes the trailer has undergone in its journey from the cinema to the iPod screen, the article focuses on the new mobility of these trailers, the shrinking screen size, and how audience participation with these texts has influenced both trailer production and distribution techniques. Exploring these texts, and their technological display, reveals how modern distribution techniques have created a shifting and interactive relationship between film studio and audience. Key words: trailer, technology, Internet, iPod, videophone, aesthetics, film promotion 2 In the current atmosphere of uncertainty over how film and television programmes are made available both online and to mobile media players, this article will focus on a visual text that regularly moves between the multiple screens of cinema, television, computer and mobile phone: the film trailer. A unique text that has often been overlooked in studies of film and media, trailer analysis reveals new approaches to traditional concerns such as stardom, genre and narrative, and engages in more recent debates on interactivity and textual mobility. -

BEFORE the PHILOSOPHY There Are Several Ways That We Might Explain the Location of the Matrix

ONE BEFORE THE 7 PHILOSOPHY UNDERSTANDING THE FILMS BEFORE THE PHILOSOPHY I’m really struggling here. I’m trying to keep up, but I’m losing the plot. There is way too much weird shit going on around here and nothing is going the way it is supposed to go. I mean, doors that go nowhere and everywhere, programs acting like humans, multiplying agents . Oh when, when will it end? – SparksE The Matrix films often left audiences more confused than they had bargained for. Some say that their confusion began with the very first film, and was compounded with each sequel. Others understood the big picture, but found themselves a bit perplexed concerning the details. It’s safe to say that no one understands the films completely – there are always deeper levels to consider. So before we explore the more philosophical aspects of the films, I hope to clarify some of the common points of confusion. But first, I strongly encourage you to watch all three films. There are spoilers ahead. The Matrix Dreamworld You mean this isn’t real? – Neo† The Matrix is essentially a computer-generated dreamworld. It is the illusion of a world that no longer exists – a world of human technology and culture as it was at the end of the twentieth century. This illusion is pumped into the brains of millions of people who, in reality, are lying fast asleep in slime-filled cocoons. To them this virtual world seems like real life. They go to work, watch their televisions, and pay their taxes, fully believing that they are physically doing these things, when in fact they are doing them “virtually” – within their own minds. -

Ash Vs Evil Dead

Vol. 7 (1) 2020 ISSN 2311 – 3448 and RELIGION STATE, ARTICLES BOOK REVIEWS CHURCH ATION R STATE, Alexander Pavlov. Hyper-Real Alexander Agadjanian. Review of: Religion, Lovecraft, and the Cult Viktor Shnirel’man. 2017. “Koleno of the Evil Dead Danovo”. Eskhatologiia i antisemitizm v DMINIST sovremennoi Rossii [“The Tribe of Dan.” A Alexander Pisarev. The Conflict Eschatology and Antisemitism in RELIGION of Immortalities: The Biopolitics of the Cerebral Subject and Religious Modern Russia]. Moscow: Izdatel’stvo Life in Altered Carbon BBI (in Russian). — 631 p. UBLIC P Nikolai Afanasov. The Depressed and AND Messiah: Religion, Science Fiction, and Postmodernism in Neon Genesis Evangelion Leonid Moyzhes. Dragon Age: CONOMY E CHURCH Inquisition: A Christian Message in a Postsecular World Maksim Podvalnyi. Religious Cults in the Fictional Universe of the RPG ATIONAL N The Witcher OF CADEMY A Vol. 7 Vol. 7 (1) 2020 ESIDENTIAL R P (1) 2020 USSIAN R ISSN 2311 – 3448 STATE, RELIGION and CHURCH Vol. 7 (1) 2020 Russian Presidential Academy of National Economy and Public Administration Russian Presidential Academy of National Moscow, 2020 editors Dmitry Uzlaner (editor-in-chief ), Patrick Brown (editor), Alexander Agadjanian, Alexander Kyrlezhev design Sergei Zinoviev, Ekaterina Trushina layout Anastasia Meyerson State, Religion and Church is an academic peer- reviewed journal devoted to the interdisciplinary scholarly study of religion. Published twice yearly under the aegis of the Russian Presidential Academy of National Economy and Public Administration. editorial board Alexey Beglov (Russia), Mirko Blagojević (Serbia), Thomas Bremer (Germany), Grace Davie (UK), Vyacheslav Karpov (USA), Vladimir Malyavin (Republic of China), Brian Horowitz (USA), Vasilios Makrides (Germany), Bernice Martin (UK), Alexander Panchenko (Russia), Randall A. -

Matrix in the Context of Belief Systems İnanç Sistemleri Bağlamında Matrix

Ş. Kurt, ODÜ Sosyal Bilimler Araştırmaları Dergisi, Temmuz 2020; 10 (2), 508-527 ∙ 508 Matrix in the Context of Belief Systems İnanç Sistemleri Bağlamında Matrix ARAŞTIRMA MAKALESI Şule KURT1 Gönderim Tarihi: 17.12.2019 | Kabul Tarihi: 23.06.2020 Abstract The necessity of questioning human existence appears to be the most fundamental condition in the process of seeking meaning in the world. In the process of making sense of the outside world, man enables his own story to be formed and conveyed through an attempt to reproduce and form himself ideologically. Myth as a form reality. Myth, which is an expression of faith, affects the preservation of morality, the powerful structuring and of meaning is the fiction of social reality. Myth is not only a story told in primitive communities but a living meaning by analyzing this existence; myths and belief systems are discussed in the context of sociological methodspreading within of religious the scope rituals. of communicative In this study, knowledge action. Mythical and understanding, stories which the formed plane inof theexistence ancient and times finding are are constructud and reproduced by adapting to the power reality of mainstream cinema. cultural tools that continue to be effective today. As such, myths which reflect the power of mythological gods analysis of this existence; It has been handled with the descriptive method within the scope of the communica- tion Insystems this study, of beliefs information such as mythsand understanding and shamanism. in the example of Matrix film, the plane of existence and the nothing more than just a revelation, examining the future of humanity and describes the collective imagination According to the findings; Matrix is a science fiction movie that is so inspiring and impressive that it is elements in the Matrix scenario, he conveyed the problem of making sense of one's own existence and the universeforward-looking. -

The Matrix Trilogy's Postmodern Movie Messiah

Journal of Religion & Film Volume 9 Issue 2 October 2005 Article 7 October 2005 He is the One: The Matrix Trilogy's Postmodern Movie Messiah Mark D. Stucky [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/jrf Recommended Citation Stucky, Mark D. (2005) "He is the One: The Matrix Trilogy's Postmodern Movie Messiah," Journal of Religion & Film: Vol. 9 : Iss. 2 , Article 7. Available at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/jrf/vol9/iss2/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Religion & Film by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. He is the One: The Matrix Trilogy's Postmodern Movie Messiah Abstract Many films have used Christ figures to enrich their stories. In The Matrix trilogy, however, the Christ figure motif goes beyond superficial plot enhancements and forms the fundamental core of the three-part story. Neo's messianic growth (in self-awareness and power) and his eventual bringing of peace and salvation to humanity form the essential plot of the trilogy. Without the messianic imagery, there could still be a story about the human struggle in the Matrix, of course, but it would be a radically different story than that presented on the screen. This article is available in Journal of Religion & Film: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/jrf/vol9/iss2/7 Stucky: He is the One Introduction The Matrix1 was a firepower-fueled film that spin-kicked filmmaking and popular culture.