Kahurangi Calling Dedicated to John George Mitchell (1942–2005)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dynamics of the Cape Farewell Upwelling Plume, New Zealand

New Zealand Journal of Marine and Freshwater Research ISSN: 0028-8330 (Print) 1175-8805 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/tnzm20 Dynamics of the Cape Farewell upwelling plume, New Zealand T. G. L. Shlrtcliffe , M. I. Moore , A. G. Cole , A. B. Viner , R. Baldwin & B. Chapman To cite this article: T. G. L. Shlrtcliffe , M. I. Moore , A. G. Cole , A. B. Viner , R. Baldwin & B. Chapman (1990) Dynamics of the Cape Farewell upwelling plume, New Zealand, New Zealand Journal of Marine and Freshwater Research, 24:4, 555-568, DOI: 10.1080/00288330.1990.9516446 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00288330.1990.9516446 Published online: 30 Mar 2010. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 108 View related articles Citing articles: 15 View citing articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=tnzm20 Download by: [203.118.161.175] Date: 14 February 2017, At: 22:09 New Zealand Journal of Marine and Freshwater Research, 1990, Vol. 24: 555-568 555 0028-8330/2404-0555 $2.50/0 © Crown copyright 1990 Dynamics of the Cape Farewell upwelling plume, New Zealand T. G. L. SfflRTCLIFFE Keywords Cape Farewell; Farewell Spit; M. I. MOORE* Kahurangi; upwelling; Research School of Earth Sciences Victoria University of Wellington INTRODUCTION P.O. Box 600, Wellington, New Zealand Cape Farewell forms the north-west comer of the *Present address: New Zealand Occanographic South Island of New Zealand (Fig. 1). To the north Institute, DSIR Marine and Freshwater, Department lies a large bay which extends c. -

Take a Look Inside

CONTENTS Acknowledgements 7 Chapter 1 Anaweka Waka 11 Chapter 2 Hopelessly Lost 36 Chapter 3 Taplin’s Hut 55 Chapter 4 Little Biddy’s Story 66 Chapter 5 The Storekeeper’s Lament 80 Chapter 6 The Flying Cray Fishers 97 Chapter 7 River Ports 110 Chapter 8 Mining Magnesite 135 Chapter 9 Ranger’s Diary 154 Chapter 10 Heritage Huts 170 Chapter 11 Tracts of Iron 186 Chapter 12 Carbon Footprints 202 Chapter 13 Chasing the Kākahi 220 Chapter 14 Roaring Lion Gold 227 Chapter 15 Modern Controversy 236 Bibliography 250 CHAPTER 1 ANAWEKA WAKA THE DISCOVERY IN EARLY JANUARY 2012 of a 6.08-metre-long adzed- timber hull section from an obviously ancient and complex composite waka (canoe) on the Kahurangi coast was a significant find that was reported nationally. Eventually, news of the discovery spread globally, such were the age and unique features of the piece. It was identified as being no less than part of one of only two known voyaging canoes in existence, dating back to the early occupation of Polynesia, a time when ongoing maritime exploration and inter-island travel were the norm. In comparison, European mariners at that time were still only guessing when it came to navigating the open ocean. Partially exposed after a major storm event, the complete hull section was dug out of an eroded sand dune behind a natural log jam of driftwood at the mouth of a small freshwater seep some 200 metres north of the Anaweka Estuary. The story of the discovery of the Anaweka waka by a naturally curious boy should not be forgotten. -

Apoidea (Insecta: Hymenoptera). Fauna of New Zealand 57, 295 Pp. Donovan, B. J. 2007

Donovan, B. J. 2007: Apoidea (Insecta: Hymenoptera). Fauna of New Zealand 57, 295 pp. EDITORIAL BOARD REPRESENTATIVES OF L ANDCARE R ESEARCH Dr D. Choquenot Landcare Research Private Bag 92170, Auckland, New Zealand Dr R. J. B. Hoare Landcare Research Private Bag 92170, Auckland, New Zealand REPRESENTATIVE OF UNIVERSITIES Dr R.M. Emberson c/- Bio-Protection and Ecology Division P.O. Box 84, Lincoln University, New Zealand REPRESENTATIVE OF M USEUMS Mr R.L. Palma Natural Environment Department Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa P.O. Box 467, Wellington, New Zealand REPRESENTATIVE OF OVERSEAS I NSTITUTIONS Dr M. J. Fletcher Director of the Collections NSW Agricultural Scientific Collections Unit Forest Road, Orange NSW 2800, Australia * * * SERIES EDITOR Dr T. K. Crosby Landcare Research Private Bag 92170, Auckland, New Zealand Fauna of New Zealand Ko te Aitanga Pepeke o Aotearoa Number / Nama 57 Apoidea (Insecta: Hymenoptera) B. J. Donovan Donovan Scientific Insect Research, Canterbury Agriculture and Science Centre, Lincoln, New Zealand [email protected] Manaaki W h e n u a P R E S S Lincoln, Canterbury, New Zealand 2007 4 Donovan (2007): Apoidea (Insecta: Hymenoptera) Copyright © Landcare Research New Zealand Ltd 2007 No part of this work covered by copyright may be reproduced or copied in any form or by any means (graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping information retrieval systems, or otherwise) without the written permission of the publisher. Cataloguing in publication Donovan, B. J. (Barry James), 1941– Apoidea (Insecta: Hymenoptera) / B. J. Donovan – Lincoln, N.Z. : Manaaki Whenua Press, Landcare Research, 2007. (Fauna of New Zealand, ISSN 0111–5383 ; no. -

A Directory of Wetlands in New Zealand: Nelson/Marlborough

A Directory of Wetlands in New Zealand NELSON/MARLBOROUGH CONSERVANCY Farewell Spit (39) Location: 40o32'S, 172o50'E. At the northern extremity of Golden Bay and the northwestern extremity of South Island, 38 km from the town of Takaka, Tasman District. Area: 11,388 ha (land area c.1,961 ha; inter-tidal zone c.9,427 ha). Altitude: Sea level to 3 m. - 155 - A Directory of Wetlands in New Zealand Overview: Farewell Spit is a classic recurved spit, approximately 30 km long, composed predominantly of uniform quartz sand derived from rivers draining westwards and transported northward by the westland current. The north is exposed to the Tasman Sea, but the south has extensive tidal mudflats. These provide feeding areas for large numbers of waterfowl. Some 95 species were recorded on the spit in March 1974, and more than 83 species of wetland birds are regularly recorded at the spit. The sand dunes provide habitat for a diverse and unusual plant community. Farewell Spit was listed as a wetland of international importance under the Ramsar Convention on 13 August 1976. Physical features: Farewell Spit is a classic recurved spit. The material forming the spit is derived from erosion of the Southern Alps and West Coast sea cliffs, transported northwards by a long-shore current. Since the estimated origin of the spit 6,500 years ago, an estimated 2.2 million cubic metres of sand have been deposited per annum. Wind transports more surface sand towards Golden Bay, although the majority of sand lies below the mean low water mark. -

Ngāti Apa Ki Te Rā Tō, Ngāti Kuia, and Rangitāne O Wairau Claims Settlement Act 2014

Reprint as at 1 August 2020 Ngāti Apa ki te Rā Tō, Ngāti Kuia, and Rangitāne o Wairau Claims Settlement Act 2014 Public Act 2014 No 19 Date of assent 22 April 2014 Commencement see section 2 Contents Page 1 Title 8 2 Commencement 8 Part 1 Preliminary matters and settlement of historical claims Subpart 1—Purpose of Act, historical accounts, acknowledgements, and apologies 3 Purpose 8 4 Provisions take effect on settlement date 9 5 Act binds the Crown 9 6 Outline 9 7 Historical accounts and the Crown’s acknowledgements and 11 apologies Historical account, acknowledgements, and apology for Ngāti Apa ki te Rā Tō 8 Summary of historical account for Ngāti Apa ki te Rā Tō 12 9 Text of acknowledgements for Ngāti Apa ki te Rā Tō 13 Note Changes authorised by subpart 2 of Part 2 of the Legislation Act 2012 have been made in this official reprint. Note 4 at the end of this reprint provides a list of the amendments incorporated. This Act is administered by the Ministry of Justice. 1 Ngāti Apa ki te Rā Tō, Ngāti Kuia, and Rangitāne o Reprinted as at Wairau Claims Settlement Act 2014 1 August 2020 10 Text of apology for Ngāti Apa ki te Rā Tō 15 Historical account, acknowledgements, and apology for Ngāti Kuia 11 Summary of historical account for Ngāti Kuia 16 12 Text of acknowledgements for Ngāti Kuia 17 13 Text of apology for Ngāti Kuia 19 Historical account, acknowledgements, and apology for Rangitāne o Wairau 14 Summary of historical account for Rangitāne o Wairau 20 15 Text of acknowledgements for Rangitāne o Wairau 22 16 Text of apology for Rangitāne -

Ray Salisbury Contents

TABLELAND THE HISTORY BEHIND MT ARTHUR KAHURANGI NATIONAL PARK RAY SALISBURY CONTENTS : .......................................... FOREWORD: Dr Nick Smith .......................................... 07 HUNTING Dead or alive 125 : ................. PREFACE ............................................................................ 09 SEARCH & RESCUE Lost and found 133 : ............ DISCOVERY: In search of .......................................... 11 CONSERVATION Seeking sanctuaries 141 : . MINING: Golden gullies ............................................... 29 RENOVATION Historic huts 151 : .............................................. GRAZING: Beef and mutton ....................................... 45 CAVING Final frontier 165 EPILOGUE ....................................................................... 177 RECREATION: Tramping and camping ................. 65 ............................................. CHAFFEYS: Alone together ........................................ 83 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 179 ................................................................... COBB DAM: Hydro power .......................................... 93 ENDNOTES 181 ............................................................ FORESTRY: Huts and tracks ..................................... 103 BIBLIOGRAPHY 187 DISCOVERY IN SEARCH OF Setting the scene Waimea when Te Rauparaha’s troops invaded some decades later. What is relevant to the history of the Tableland is the arduous route hen Polynesians first sailed across the vast Pacific to arrive in the Ngāi Tahu -

New Zealand 16 Marlborough Nelson Chapter

©Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd Marlborough & Nelson Why Go? Marlborough Region ....400 For many travellers, Marlborough and Nelson will be their Picton ........................... 400 introduction to what South Islanders refer to as the ‘Main- Marlborough Sounds ...404 land’. Having left windy Wellington, and made a white- Queen Charlotte Track ...407 knuckled crossing of Cook Strait, folk are often surprised to fi nd the sun shining and the temperature up to 10 degrees Kenepuru & Pelorus Sounds.............409 warmer. Good pals, these two neighbouring regions have much Blenheim ........................411 in common beyond an amenable climate: both boast re- Kaikoura ........................ 416 nowned coastal holiday spots, particularly the Marlborough Nelson ...........................423 Sounds and Abel Tasman National Park. There are two other Nelson Lakes national parks (Kahurangi and Nelson Lakes) and more National Park ................430 mountain ranges than you can poke a stick at. Motueka ........................432 And so it follows that these two regions have an abun- Motueka to Abel dance of luscious produce: summer cherries for a starter, Tasman ..........................435 but most famously the grapes that work their way into the Golden Bay ....................440 wineglasses of the world’s fi nest restaurants. Keep your pen- Kahurangi National knife and picnic set at the ready. Park ...............................444 When to Go? Best Places to Eat The forecast is good: Marlborough and Nelson soak up some » Green Dolphin (p 422 ) of New Zealand’s sunniest weather. January and February are the warmest months, with daytime temperatures aver- » Wither Hills (p 414 ) aging 22°C; July is the coldest, averaging 12°C. It’s wetter » Hopgood’s (p 428 ) and more windswept the closer you get to Farewell Spit and » Sans Souci Inn (p 442 ) the West Coast. -

West Coast Backcountry Fishery Report 2018

WEST COAST BACKCOUNTRY FISHERY REPORT 2018 A Summary of Angler Survey & Drift Diving Results for the West Coast Backcountry Fisheries, Conducted by Fish & Game West Coast for the 2017/2018 Sports Fishing Season. Lee Crosswell, Fish & Game Field Officer, July 2018 Staff and volunteers prepare to drift dive the Upper Mokihinui River, March 2018. WEST COAST BACKCOUNTRY FISHERY REPORT 2018 A Summary of Angler Survey & Drift Diving Results for the West Coast Backcountry Fisheries, Conducted by Fish & Game West Coast for the 2017/2018 Sports Fishing Season. Lee Crosswell, Fish & Game Field Officer, July 2018. Summary The Karamea and Mokihinui Rivers have for many years provided excellent angling opportunities for resident and visiting non-resident anglers. Following feedback of an apparent decline in the fishery status, West Coast Fish and Game designated both catchments as a Backcountry Fishery in 2016/17. This requires anglers to obtain a free Backcountry Endorsement, in doing so providing their details for an online survey following the angling season. In conjunction with the angler’s survey, drift dives were undertaken through historic dive sites in both catchments. The anglers survey has focused on evaluating fishery usage, commercial guided fishing, access methods and angler satisfaction, while offering anglers currently using the fishery the opportunity to comment on these topics and offer future management suggestions. This report summarises the backcountry survey and drift diving results for the 2017/18 season. Staff recommendations are: Survey anglers to determine if they approve of restricted access as a form of fishery management; Change the bag limit to one trout per day in the West Coast Backcountry Fishery area during the next round of regulation setting; That council receives this report. -

Kahurangi National Park

Kahurangi National Park Thc cstablishmcnt of a new national park all the boundaries of the park can be sur- "Kahurang~National Park has been was announccd on April 2 by the Minis- veyed. Once this is done, the Minister is madc possible by three years of intensive ter of Conservation, Dcnis Marshall. then in a position to recommend to the community consultation by the New Zca- Kahurangi National Park, in the north- Governor-Gencral that she gazettcs the land Conservation Authority and by west of the South Island, becomes New area, by Order-In-Council,to be a national myself.Talking with the communities, iwi Zealand's 13th national park and the scc- park. Maori and others revealed a huge body of ond largest behind Fiordland National Mr Marshall, who was camping out in support for creating national park protec- Park. The park will dwarf in size its two the park overnight, said it was an honour tion in this very special corner of New neighbours, the Abcl Tasnian National to announce such a grand and positive step Zealand," the Minister said. Park and the Nelson Lakcs National Park. towards the preservation of New Zca- Within the ncw national park's bound- It will probably take 12 months before land's natural-treasures. aries are a huge range and variety ofland- forms, plants and animals, many of them rare and endangcred, and some of them found nowhere else in New Zcaland. These include more than half of New Zcaland's 2270 plant species, of which 67 are found only in this region and 19 are nationally thrcatened. -

Conservation Campsites South Island 2019-20 Nelson

NELSON/TASMAN Note: Campsites 1–8 and 11 are pack in, pack out (no rubbish or recycling facilities). See page 3. Westhaven (Te Tai Tapu) Marine Reserve North-west Nelson Forest Park 1 Kahurangi Marine Takaka Tonga Island Reserve 2 Marine Reserve ABEL TASMAN NATIONAL PARK 60 3 Horoirangi Motueka Marine KAHURANGI Reserve NATIONAL 60 6 Karamea PARK NELSON Picton Nelson Visitor Centre 4 6 Wakefield 1 Mount 5 6 Richmond Forest Park BLENHEIM 67 6 63 6 Westport 7 9 10 Murchison 6 8 Rotoiti/Nelson Lakes 1 Visitor Centre 69 65 11 Punakaiki NELSON Marine ReservePunakaiki Reefton LAKES NATIONAL PARK 7 6 7 Kaikōura Greymouth 70 Hanmer Springs 7 Kumara Nelson Visitor Centre P Millers Acre/Taha o te Awa Hokitika 73 79 Trafalgar St, Nelson 1 P (03) 546 9339 7 6 P [email protected] Rotoiti / Nelson Lakes Visitor Centre Waiau Glacier Coast P View Road, St Arnaud Marine Reserve P (03) 521 1806 Oxford 72 Rangiora 73 0 25 50 km P [email protected] Kaiapoi Franz Josef/Waiau 77 73 CHRISTCHURCH Methven 5 6 1 72 77 Lake 75 Tauparikākā Ellesmere Marine Reserve Akaroa Haast 80 ASHBURTON Lake 1 6 Pukaki 8 Fairlie Geraldine 79 Hautai Marine Temuka Reserve Twizel 8 Makaroa 8 TIMARU Lake Hāwea 8 1 6 Lake 83 Wanaka Waimate Wanaka Kurow Milford Sound 82 94 6 83 Arrowtown 85 6 Cromwell OAMARU QUEENSTOWN 8 Ranfurly Lake Clyde Wakatipu Alexandra 85 Lake Te Anau 94 6 Palmerston Te Anau 87 8 Lake Waikouaiti Manapouri 94 1 Mossburn Lumsden DUNEDIN 94 90 Fairfield Dipton 8 1 96 6 GORE Milton Winton 1 96 Mataura Balclutha 1 Kaka Point 99 Riverton/ INVERCARGILL Aparima Legend 1 Visitor centre " Campsite Oban Stewart Island/ National park Rakiura Conservation park Other public conservation land Marine reserve Marine mammal sanctuary 0 25 50 100 km NELSON/TASMAN Photo: DOC 1 Tōtaranui 269 This large and very popular campsite is a great base for activities; it’s a good entrance point to the Abel Tasman Coast Track. -

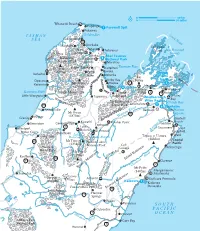

P a C I F I C O C E a N S O U

050 km 0 30 miles Wharariki Beach Puponga Farewell Spit Pakawau T A S M A N Golden Bay Cook Strait S E A Collingwood 60 Onekaka Bainham D'Urville Pupu Pohara Totaranui Island Marlborough y Trac Springs Sounds h k Takaka ap Abel Tasman e Kahurangi H Canaan National Park National Park Downs Marahau Tasman Bay Mt Domett Upper Takaka Kaiteriteri (1646m) Cobb Riwaka Queen y Ferry to Kohaihai River Motueka w Rai Charlotte Wellington H Moutere Oparara Ruby Bay Valley Track Mt Arthur Valley Mapua 6 Karamea Havelock (1795m) Rabbit Nelson ueka Hwy Is Pelorus Waikawa 6 Karamea Bight Tasman Mountains Stoke Bridge 1 Picton Mot Little Wanganui Tapawera Richmond Marlborough Whites Wangape Bay Mt Richmond Wine Region ka ck Cloudy Bay 67 Tra Forest Park Onamalutu er Blenheim Seddonville ge iv Wairau an u R Renwick Mt Owen d R ira 65 Lagoons (1875m) on Wa Granity Hector ichm r R ive Marfells Kawatiri Kowhai Point R Beach Denniston Gowanbridge Tophouse Seddon 6 Lake Westport Grassmere Cape Rotoroa St Arnaud Awatere Campbell Buller Gorge Murchison Lake Ward Inangahua Rotoroa Lake Rotoiti Tapuae-o-Uenuru (2885m) Coastal 69 Mt Travers Nelson Lakes Pacific (2338m) National Park Cob Victoria Cottage ras Kekerengu Forest Park ou Mt Una Rd aik (2300m) eron d K Reefton ch River 65 Inlan 7 -A Clarence rth l) 1 o Clarence Spencer Mountains na Mt Fyffe Mangamaunu; lesw aso (1402m) Ikamatua o e Meatworks (S Lewis M Springs Acheron Kaikoura Peninsula Junction Pass KaikourasKaikoura Hanmer Forest ardConway Riv Kaikoura Peninsula Conservation Park Seaw70 Lake Sumner Forest Park 7 Hanmer iver Springs R er Waiau Waiau Parnassus S O U T H Culverden P A C I F I C 7 O C E A N Huru Cheviot nui r Arthur's Pass Rive Gore Bay National Park 1 Hurunui. -

Download the Intentions Wilder Spots

Nelson Tramping Club March 2016 Newsletter of the NELSON TRAMPING CLUB Founded 1934, Nelson, New Zealand www.nelsontrampingclub.org.nz PRESIDENT’s PIECE : Keep your powder dry No cotton – Cotton underwear and tee-shirts quickly absorb rainwater and sweat, are slow to A couple of recent trips in the hills provided dry and provide little insulation. Hypothermia can me with some reminders of the pleasures and follies arise under mild conditions, especially with wind. of our wonderful pursuit. Here are a few gems of The core body is the key to keeping the extremities wisdom that I have gathered from these trips and warm. Make sure you use wool or synthetic layers, others. I offer them in the spirit of instruction, not even in summer, as these provide some insulation destruction. Some of the follies are my own; others when damp. And carry some spares. by tramping friends who shall remain nameless. Tenting – it is a challenge to keep gear dry in It is axiomatic that some of our trips will be wet conditions including the making or breaking conducted in less than ideal weather. Even careful of camp. Modern nylon tents with flies do not prior study of weather maps cannot preclude all risk generally leak much if in good condition. But care of wind and rain for multi-day trips. I believe an and discipline are essential so tracking of water unduly cautious approach to trip planning detracts into the tent and gear is minimised. A pack cover from the totality of our experience in the hills. The is excellent, so the wet pack can stay outside the changeable New Zealand climate indeed offers tent.