Anurupa Roy Phd Dissertation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Prof. Mrinal Datta Chaudhuri, MDC to All His Students, and Mrinal-Da to His Junior Colleagues and Friends, Was a Legendary Teacher of the Delhi School of Economics

Prof. Mrinal Dutta Chaudhuri Memorial Meeting Tuesday, 21st July, 2015 at DELHI SCHOOL OF ECONOMICS University of Delhi Delhi – 110007 1 1934-2015 2 3 PROGRAMME Prof. Pami Dua, Director, DSE - Opening Remarks (and coordination) Dr. Malay Dutta Chaudhury, Brother of Late Prof. Mrinal Dutta Chaudhuri Prof. Aditya Bhattacharjea, HOD Economics, DSE - Life Sketch Condolence Messages delivered by : Dr. Manmohan Singh, Former Prime Minister of India (read by Prof. Pami Dua) Prof. K.L.Krishna Prof. Badal Mukherji Prof. K. Sundaram Prof. Pulin B. Nayak Prof. Partha Sen Prof. T.C.A. Anant Prof. Kirit Parikh Mr. Nitin Desai Prof. J.P.S. Uberoi Prof. Pranab Bardhan Prof. Andre Beteille, Prof.Amartya Sen (read by Prof. Rohini Somanathan) Prof. Kaushik Basu, Dr. Omkar Goswami (read by Prof. Ashwini Deshpande) Prof. Abhijit Banerjee, Prof. Anjan Mukherji, Dr. Subir Gokaran (read by Prof. Aditya Bhattacharjea) Prof. Prasanta Pattanaik, Prof. Bhaskar Dutta, Prof. Dilip Mookherjee (read by Prof. Sudhir Shah) Dr. Sudipto Mundle Prof. Ranjan Ray, Prof. Vikas Chitre (read by Prof. Aditya Bhattacharjea) Prof. Adi Bhawani Mr. Paranjoy Guha Thakurta Prof. Meenakshi Thapan Prof. B.B.Bhattacharya, Prof. Maitreesh Ghatak, Prof.Gopal Kadekodi, Prof. Shashak Bhide, Prof.V.S.Minocha, Prof.Ranganath Bhardwaj, Ms. Jasleen Kaur (read by Prof. Pami Dua) 4 Prof. Pami Dua, Director, DSE We all miss Professor Mrinal Dutta Chaudhuri deeply and pay our heartfelt and sincere condolences to his family and friends. We thank Dr. Malay Dutta Chaudhuri, Mrinal’s brother for being with us today. We also thank Dr. Rajat Baishya, his close relative for gracing this occasion. -

Tollygunge Assembly West Bengal Factbook

Editor & Director Dr. R.K. Thukral Research Editor Dr. Shafeeq Rahman Compiled, Researched and Published by Datanet India Pvt. Ltd. D-100, 1st Floor, Okhla Industrial Area, Phase-I, New Delhi- 110020. Ph.: 91-11- 43580781, 26810964-65-66 Email : [email protected] Website : www.electionsinindia.com Online Book Store : www.datanetindia-ebooks.com Report No. : AFB/WB-152-0619 ISBN : 978-93-5293-827-8 First Edition : January, 2018 Third Updated Edition : June, 2019 Price : Rs. 11500/- US$ 310 © Datanet India Pvt. Ltd. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, mechanical photocopying, photographing, scanning, recording or otherwise without the prior written permission of the publisher. Please refer to Disclaimer at page no. 167 for the use of this publication. Printed in India No. Particulars Page No. Introduction 1 Assembly Constituency at a Glance | Features of Assembly as per 1-2 Delimitation Commission of India (2008) Location and Political Maps 2 Location Map | Boundaries of Assembly Constituency in District | Boundaries 3-9 of Assembly Constituency under Parliamentary Constituency | Ward-wise Winner Parties- 2019, 2016, 2014, 2011 and 2009 Administrative Setup 3 District | Sub-district | Towns | Villages | Inhabited Villages | Uninhabited 10 Villages | Village Panchayat | Intermediate Panchayat Demographics 4 Population | Households | Rural/Urban Population | Ward by Population Size | 11-12 Sex Ratio (Total & 0-6 Years) | Religious -

SSC JE 2018 General Awareness Paper

QID : 651 - Income and Expenditure Account is ___________. Options: 1) Property account 2) Personal Account 3) Nominal Account 4) Capital Account Correct Answer: Nominal Account QID : 652 - Commodity or product differentiation is found in which market? Options: 1) Perfect Competition Market 2) Monopoly Market 3) Imperfect Competition Market 4) No option is correct Correct Answer: Imperfect Competition Market QID : 653 - The economist who for the first time scientifically determined National Income in India is ___________. Options: 1) Jagdish Bhagwati 2) V.K.R.V. Rao 3) Kaushik Basu 4) Manmohan Singh Correct Answer: V.K.R.V. Rao QID : 654 - Which of the following is not a part of the non-plan expenditure of central government? Options: 1) Interest payment 2) Grants to states 3) Electrification 4) Subsidy Correct Answer: Electrification QID : 655 - The percentage of decadal growth of population of India during 2001-2011 as per census 2011 is ___________. Options: 1) 15.89 2) 17.64 3) 19.21 4) 21.54 Correct Answer: 17.64 QID : 656 - The concept of Constitution first originated in which of the following countries? Options: 1) Italy 2) China 3) Britain 4) France Correct Answer: Britain QID : 657 - The Parliament has been given power to make laws regarding citizenship under which article of the Constitution of India? Options: 1) Article 5 2) Article 7 3) Article 9 4) Article 11 Correct Answer: Article 11 QID : 658 - Which one of the following cannot be the ground for proclamation of Emergency under the Constitution of India? Options: 1) War 2) Armed rebellion 3) External aggression 4) Internal disturbance Correct Answer: Internal disturbance QID : 659 - The 100th amendment in Indian Constitution provides ___________. -

WEST BENGAL POLLUTION CONTROL BOARD (Department of Environment, Government of West Bengal)

WEST BENGAL POLLUTION CONTROL BOARD (Department of Environment, Government of West Bengal) Paribesh Bhawan,10A, Block – LA, Sector III, Salt Lake Kolkata – 700 098, Ph.: (033)2335 8212, Fax : (033)2335-8073 Website: www.wbpcb.gov.in Memo No. 2097-5L/WPB/2012/U-00288 Dated : 03-10-2012 CLOSURE ORDER WITH DISCONNECTION OF ELECTRICITY WHEREAS a public complaint was received by the West Bengal Pollution Control Board (hereinafter will be referred to as the ÁState Board©), on 02-01-2012, 03-01-2012 and subsequently on 05-07-2012 against M/s. Unique Switch Gear located at 46 Madhusudan Palchowdhury 1 st Bye Lane, P.S. Howrah, Dist. Howrah, alleging noise and air pollution due to engineering and sheet metal fabrication activities with spray painting. AND WHEREAS the unit was called for hearing on 15-02-2012 by the State Board to remain present with all statutory licenses, including `Consent to Establish(NOC)/Consent to Operate' of the State Board but nobody appeared on behalf of the unit. AND WHEREAS the unit was called for hearing again on 09-04-2012 by the State Board due to its gross violation of environmental norms and this time also nobody appeared on behalf of the unit and the unit was directed to submit the copy of trade licence and NOC & Consent of State Board within 24-04-2012 positively. AND WHEREAS the unit was called for hearing again on 27-08-2012 and this time also nobody appeared on behalf of the unit. NOW THEREFORE, considering non-compliance of directions of State Board, M/s. -

List of Contact Person As Well As Hospitals of KPGM Policy '2017-18'

List of Contact Person as well as Hospitals of KPGM Policy ’2017-18’ Insurance Company : National Insurance Company Limited, Division – XXII, CRO – II, Kolkata-700 001. TPA : MDIndia Health Insurance TPA Pvt. Ltd. Office : 18, Lalbazar Street, Kolkata – 700 001. Phone Number : 033 – 2214 – 1936 / 1937 : Dr. Pijush Kanti Ghosh - 93320-80207 For Cashless : Mr. Soumen Jena - 99321-79757 : Dr. Sukanta Hens - 76992-23715 Reimbursement Claim : Mr. T. N. Das - 87980-85986 : 10:00 a.m. to 5:30 p.m. (Monday – Friday) Office Hours : 10:00 a.m. to 2:00 p.m. (Saturday) Claim Co-Coordinator : Mr. T. N. Das - 87980-85986 Nodal Officer, KPGM : Rabi Bhusan Paul - 94326 – 12632 KPGM Stuff : ASI - Kanchan Kr. Chowbey - 98366 - 32468 KPGM Office, Lalbazar : 033 – 2250 – 5156 List of empanelled Hospitals / Nursing Homes in Kolkata, Vellore and Districts for cashless facility for the members of Kolkata Police Group Mediclaim Policy’2017-18. K.P.G.M HOSPITAL LIST- 2017-2018 (KOLKATA) Sl. Contact Hospital Name Location Address Contact No No Person P-4&5, Gariahat Road Block-A, 033-66260000/ 1 AMRI -Dhakuria Kolkata Scheme-L11, Dhakuria, Kolkata Suvendu Pal 99030-11694 700029 230 Barakhola Lane, Purba Jadavpur, Behind Metro Cash n 033-66061041/ 2 AMRI -Mukundapur Kolkata Carry, Mukundapur, Kolkata - Dr Sukhendu 98310-65329 700099 JC - 16 & 17 Saltlake City, KB 033-66147700/ 3 AMRI -Saltlake Kolkata Block, Sector III, Kolkata - 700098 Victar Nandi 98310-13578 All Asia Medical 8B, Garcha First Lane, Beside 033-40012200/ 4 Institute (Harsh Kolkata Gariahat Pantaloons, Ballygunge, Ranjit Ukil 98305-92300 Medical) Kolkata - 700019 033-24567890/ B M Birla Heart 1, National Library Ave, Sector 1, 5 Kolkata S. -

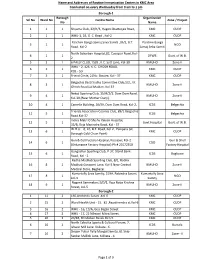

Name and Addresses of Routine Immunization Centers in KMC Area

Name and Addresses of Routine Immunization Centers in KMC Area Conducted on every Wednesday from 9 am to 1 pm Borough-1 Borough Organization Srl No Ward No Centre Name Zone / Project No Name 1 1 1 Shyama Club, 22/H/3, Hagen Chatterjee Road, KMC CUDP 2 1 1 WHU-1, 1B, G. C. Road , Kol-2 KMC CUDP Paschim Banga Samaj Seva Samiti ,35/2, B.T. Paschim Banga 3 1 1 NGO Road, Kol-2 Samaj Seba Samiti North Subarban Hospital,82, Cossipur Road, Kol- 4 1 1 DFWB Govt. of W.B. 2 5 2 1 6 PALLY CLUB, 15/B , K.C. Sett Lane, Kol-30 KMUHO Zone-II WHU - 2, 126, K. C. GHOSH ROAD, 6 2 1 KMC CUDP KOL - 50 7 3 1 Friend Circle, 21No. Bustee, Kol - 37 KMC CUDP Belgachia Basti Sudha Committee Club,1/2, J.K. 8 3 1 KMUHO Zone-II Ghosh Road,Lal Maidan, Kol-37 Netaji Sporting Club, 15/H/2/1, Dum Dum Road, 9 4 1 KMUHO Zone-II Kol-30,(Near Mother Diary). 10 4 1 Camelia Building, 26/59, Dum Dum Road, Kol-2, ICDS Belgachia Friends Association Cosmos Club, 89/1 Belgachia 11 5 1 ICDS Belgachia Road.Kol-37 Indira Matri O Shishu Kalyan Hospital, 12 5 1 Govt.Hospital Govt. of W.B. 35/B, Raja Manindra Road, Kol - 37 W.H.U. - 6, 10, B.T. Road, Kol-2 , Paikpara (at 13 6 1 KMC CUDP Borough Cold Chain Point) Gun & Cell Factory Hospital, Kossipur, Kol-2 Gun & Shell 14 6 1 CGO (Ordanance Factory Hospital) Ph # 25572350 Factory Hospital Gangadhar Sporting Club, P-37, Stand Bank 15 6 1 ICDS Bagbazar Road, Kol - 2 Radha Madhab Sporting Club, 8/1, Radha 16 8 1 Madhab Goswami Lane, Kol-3.Near Central KMUHO Zone-II Medical Store, Bagbazar Kumartully Seva Samity, 519A, Rabindra Sarani, Kumartully Seva 17 8 1 NGO kol-3 Samity Nagarik Sammelani,3/D/1, Raja Naba Krishna 18 9 1 KMUHO Zone-II Street, kol-5 Borough-2 1 11 2 160,Arobindu Sarani ,Kol-6 KMC CUDP 2 15 2 Ward Health Unit - 15. -

West Bengal Police Recruitment Board Araksha Bhaban, Sector – Ii, Block - Dj Salt Lake City, Kolkata – 700091

WEST BENGAL POLICE RECRUITMENT BOARD ARAKSHA BHABAN, SECTOR – II, BLOCK - DJ SALT LAKE CITY, KOLKATA – 700091 INFORMATION TO APPLICANTS FOR ‘OFF-LINE’ SUBMISSION OF APPLICATION FOR RECRUITMENT TO THE POST OF STAFF OFFICER CUM INSTRUCTOR IN CIVIL DEFENCE ORGANISATION WEST BENGAL UNDER THE DEPARTMENT OF DISASTER MANAGEMENT & CIVIL DEFENCE, GOVT. OF WEST BENGAL 1. NAME OF THE POST & PAY SCALE:- Staff Officer-cum-Instructor in Civil Defence Organisation, West Bengal under the Department of Disaster Management & Civil Defence, Govt. of West Bengal in the Pay Scale 7,100 – 37,600/- (i.e. Pay Band-3) + Grade Pay Rs. 3,600/- plus other admissible allowances. 2. NUMBER OF VACANCIES :- Staff Officer-cum-Instructor in Sl. No. Category Civil Defence Organisation, West Bengal 1. Unreserved (UR) 67 2. Scheduled Caste 28 3. Scheduled Tribe 08 4. OBC - A 13 5. OBC - B 09 TOTAL 125 NOTE : - Total vacancies as stated above is purely provisional and subject to marginal changes. 3. ELIGIBILITY :- A. The applicant must be a citizen of India. B. Educational Qualification :- The applicant must have a bachelor’s degree in any discipline from a recognized university or its equivalent. C. Language :- (i) The applicant must be able to speak, read and write Bengali Language. However, this provision will not be applicable to persons who are permanent residents of hill sub-divisions of Darjeeling and Kalimpong Districts. (ii) For applicants from hill sub-divisions of Darjeeling and Kalimpong District, the provisions laid down in the West Bengal Official language Act, 1961 will be applicable. D. AGE :- The applicant must not be below 20 years and not more than 39 years as on 01.01.2019. -

Rohini Pande

ROHINI PANDE 27 Hillhouse Avenue 203.432.3637(w) PO Box 208269 [email protected] New Haven, CT 06520-8269 https://campuspress.yale.edu/rpande EDUCATION 1999 Ph.D., Economics, London School of Economics 1995 M.Sc. in Economics, London School of Economics (Distinction) 1994 MA in Philosophy, Politics and Economics, Oxford University 1992 BA (Hons.) in Economics, St. Stephens College, Delhi University PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE ACADEMIC POSITIONS 2019 – Henry J. Heinz II Professor of Economics, Yale University 2018 – 2019 Rafik Hariri Professor of International Political Economy, Harvard Kennedy School, Harvard University 2006 – 2017 Mohammed Kamal Professor of Public Policy, Harvard Kennedy School, Harvard University 2005 – 2006 Associate Professor of Economics, Yale University 2003 – 2005 Assistant Professor of Economics, Yale University 1999 – 2003 Assistant Professor of Economics, Columbia University VISITING POSITIONS April 2018 Ta-Chung Liu Distinguished Visitor at Becker Friedman Institute, UChicago Spring 2017 Visiting Professor of Economics, University of Pompeu Fabra and Stanford Fall 2010 Visiting Professor of Economics, London School of Economics Spring 2006 Visiting Associate Professor of Economics, University of California, Berkeley Fall 2005 Visiting Associate Professor of Economics, Columbia University 2002 – 2003 Visiting Assistant Professor of Economics, MIT CURRENT PROFESSIONAL ACTIVITIES AND SERVICES 2019 – Director, Economic Growth Center Yale University 2019 – Co-editor, American Economic Review: Insights 2014 – IZA -

Ward No: 098 ULB Name :KOLKATA MC ULB CODE: 79

BPL LIST-KOLKATA MUNICIPAL CORPORATION Ward No: 098 ULB Name :KOLKATA MC ULB CODE: 79 Member Sl Address Name of Family Head Son/Daughter/Wife of BPL ID Year No Male Female Total 1 7/2 KHANPUR SHAID NAGAR ABALA GAYAN LT. GOBINDA GAYAN 2 2 4 2 2 GANGULY BAGAN 23A GANGULY BAGAN KOL-92 ABHA BAGCHI LT. BHABANI PADA BAGCHI 4 3 7 3 3 NETAJI NAGAR 11/23 NETAJI NAGAR ALOK MUKERJEE LT BIMAL KANTI MUKERJEE 2 2 4 6 4 55 KHANPUR SOHID NAGAR AMAL BISWAS LATE GOPAL BISWAS 3 1 4 7 5 NETAJI NAGAR 2/42 NETAJI NAGAR KOL-92 AMAL DAS LT. MANMATO DAS 3 0 3 8 6 SUBHAS PALLY 33 SUBHAS PALLY, KOL 92 AMITA DUTTA LT LAKSHMINARAYAN DUTTA 0 1 1 9 7 7/11B NETAJI NAGAR KOL-92 AMIYA BALA SIL LT.NARENDRA NATH SIL 0 3 3 10 8 SUBHAS PALLY 32A/1 SUBHAS PALLY, KOL 92 ANIMA BHATTHACHARYA LT MUKUL BHATTACHARYA 0 1 1 11 9 GANGULY BAGAN GANGULY BAGAN KOL-92 ANIMA DEVNATH PRAFULLY DEVNATH 1 4 5 12 10 9A KHANPUR SOHIDNAGAR ANJALI SINHA JIBAN SINHA 1 2 3 13 11 NETAJI NAGAR 8/76C NETAJI NAGAR ANJAN DEY 2 2 4 14 12 1/37 NETAJI NAGAR KOL-92 ANJU DUTTA LATE SUSHIL KUMAR DUTTA 1 2 3 15 13 BIJOYGAR 5/17 BIJOYGAR ANURUPA MUKHERJEE LATE KOLLAN KUMAR MUKHERJ 0 1 1 16 14 POLLYSREE 15/1 POLLYSREE APURBA DEY HARAPRASANNA DEY 2 1 3 17 15 1/2/5 KHANPUR SAHID NAGAR ARABINDA BISWAS LATE SUSHIL BISWAS 1 1 2 18 16 NETAJI NAGAR 1/40 NETAJI NAGAR KOL-92 ARABINDA DAS LT. -

Kolkata, Friday, 02N D February, 2018

Registered No. C604 Vol No. 02 of 2018 WEST BENGAL POLICE GAZETTE Published by Authority For departmental use only K O L K A T A , F R I D A Y , 02 N D F EBRUARY , 2018 PART - I GOVERNMENT OF WEST BENGAL Home and Hill Affairs Department Police Establishment Branch Nabanna, 325, Sarat Chatterjee Road Mandirtala, Shibpur, From: Shri A. Sen, Howrah – 711 102 From : K. Chowdhury, Assistant Secretary to the Govt. of West Bengal. To : The Director General & Inspector General of Police, West Bengal, Bhabani Bhawan, Alipore, Kolkata – 700 027. No. 149 – PL/PB/3P-08/17 Dated : 10.01.2018 Sub. : Engagement of 55 (fifty five) Drivers on contractual basis in IB, West Bengal. The undersigned is directed to refer to his notes vide No. ORG-213/17 dated 11.10.1017 in the Secretariat File No. PB/3P-08/17 and Memo. No. 1151/ORG dated 08.08.2017 of Addl. Director General & Inspector General of Police, Establishment, West Bengal and to say that the proposal for engagement of 55 (fifty five) Drivers on contractual basis in IB, West Bengal was under active consideration of the Government for some time past. 2. Now, the undersigned is directed to say that the Governor, after careful consideration of the matter, has been pleased to accord approval for engagement of 55 (fifty five) Drivers on contractual basis in IB, West Bengal for driving the existing vehicles of IB, West Bengal. Such contractual engagement should be made purely on temporary basis only for a period of 1 (one) year at a consolidated remuneration of Rs. -

Hawkers' Movement in Kolkata, 1975-2007

NOTES hawkers’ cause. More than 32 street-based Hawkers’ Movement hawker unions, with an affiliation to the mainstream political parties other than the in Kolkata, 1975-2007 ruling Communist Party of India (Marxist), better known as CPI(M), constitute the body of the HSC. The CPI(M)’s labour wing, Centre Ritajyoti Bandyopadhyay of Indian Trade Unions (CITU), has a hawk- er branch called “Calcutta Street Hawkers’ In Kolkata, pavement hawking is n recent years, the issue of hawkers Union” that remains outside the HSC. The an everyday phenomenon and (street vendors) occupying public space present paper seeks to document the hawk- hawkers represent one of the Iof the pavements, which should “right- ers’ movement in Kolkata and also the evo- fully” belong to pedestrians alone, has lution of the mechanics of management of largest, more organised and more invited much controversy. The practice the pavement hawking on a political ter- militant sectors in the informal of hawking attracts critical scholarship rain in the city in the last three decades, economy. This note documents because it stands at the intersection of with special reference to the activities of the hawkers’ movement in the city several big questions concerning urban the HSC. The paper is based on the author’s governance, government co-option and archival and field research on this subject. and reflects on the everyday forms of resistance (Cross 1998), property nature of governance. and law (Chatterjee 2004), rights and the Operation Hawker, 1975 very notion of public space (Bandyopadhyay In 1975, the representatives of Calcutta 2007), mass political activism in the context M unicipal Corporation (henceforth corpora- of electoral democracy (Chatterjee 2004), tion), Calcutta Metropolitan Development survival strategies of the urban poor in the Authority (CMDA), and the public works context of neoliberal reforms (Bayat 2000), d epartment (PWD) jointly took a “decision” and so forth. -

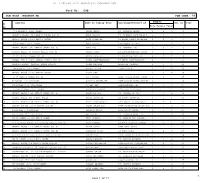

Date Wise Details of Covid Vaccination Session Plan

Date wise details of Covid Vaccination session plan Name of the District: Darjeeling Dr Sanyukta Liu Name & Mobile no of the District Nodal Officer: Contact No of District Control Room: 8250237835 7001866136 Sl. Mobile No of CVC Adress of CVC site(name of hospital/ Type of vaccine to be used( Name of CVC Site Name of CVC Manager Remarks No Manager health centre, block/ ward/ village etc) Covishield/ Covaxine) 1 Darjeeling DH 1 Dr. Kumar Sariswal 9851937730 Darjeeling DH COVAXIN 2 Darjeeling DH 2 Dr. Kumar Sariswal 9851937730 Darjeeling DH COVISHIELD 3 Darjeeling UPCH Ghoom Dr. Kumar Sariswal 9851937730 Darjeeling UPCH Ghoom COVISHIELD 4 Kurseong SDH 1 Bijay Sinchury 7063071718 Kurseong SDH COVAXIN 5 Kurseong SDH 2 Bijay Sinchury 7063071718 Kurseong SDH COVISHIELD 6 Siliguri DH1 Koushik Roy 9851235672 Siliguri DH COVAXIN 7 SiliguriDH 2 Koushik Roy 9851235672 SiliguriDH COVISHIELD 8 NBMCH 1 (PSM) Goutam Das 9679230501 NBMCH COVAXIN 9 NBCMCH 2 Goutam Das 9679230501 NBCMCH COVISHIELD 10 Matigara BPHC 1 DR. Sohom Sen 9435389025 Matigara BPHC COVAXIN 11 Matigara BPHC 2 DR. Sohom Sen 9435389025 Matigara BPHC COVISHIELD 12 Kharibari RH 1 Dr. Alam 9804370580 Kharibari RH COVAXIN 13 Kharibari RH 2 Dr. Alam 9804370580 Kharibari RH COVISHIELD 14 Naxalbari RH 1 Dr.Kuntal Ghosh 9832159414 Naxalbari RH COVAXIN 15 Naxalbari RH 2 Dr.Kuntal Ghosh 9832159414 Naxalbari RH COVISHIELD 16 Phansidewa RH 1 Dr. Arunabha Das 7908844346 Phansidewa RH COVAXIN 17 Phansidewa RH 2 Dr. Arunabha Das 7908844346 Phansidewa RH COVISHIELD 18 Matri Sadan Dr. Sanjib Majumder 9434328017 Matri Sadan COVISHIELD 19 SMC UPHC7 1 Dr. Sanjib Majumder 9434328017 SMC UPHC7 COVAXIN 20 SMC UPHC7 2 Dr.