Moth Cocoons

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Butterflies and Moths of Brevard County, Florida, United States

Heliothis ononis Flax Bollworm Moth Coptotriche aenea Blackberry Leafminer Argyresthia canadensis Apyrrothrix araxes Dull Firetip Phocides pigmalion Mangrove Skipper Phocides belus Belus Skipper Phocides palemon Guava Skipper Phocides urania Urania skipper Proteides mercurius Mercurial Skipper Epargyreus zestos Zestos Skipper Epargyreus clarus Silver-spotted Skipper Epargyreus spanna Hispaniolan Silverdrop Epargyreus exadeus Broken Silverdrop Polygonus leo Hammock Skipper Polygonus savigny Manuel's Skipper Chioides albofasciatus White-striped Longtail Chioides zilpa Zilpa Longtail Chioides ixion Hispaniolan Longtail Aguna asander Gold-spotted Aguna Aguna claxon Emerald Aguna Aguna metophis Tailed Aguna Typhedanus undulatus Mottled Longtail Typhedanus ampyx Gold-tufted Skipper Polythrix octomaculata Eight-spotted Longtail Polythrix mexicanus Mexican Longtail Polythrix asine Asine Longtail Polythrix caunus (Herrich-Schäffer, 1869) Zestusa dorus Short-tailed Skipper Codatractus carlos Carlos' Mottled-Skipper Codatractus alcaeus White-crescent Longtail Codatractus yucatanus Yucatan Mottled-Skipper Codatractus arizonensis Arizona Skipper Codatractus valeriana Valeriana Skipper Urbanus proteus Long-tailed Skipper Urbanus viterboana Bluish Longtail Urbanus belli Double-striped Longtail Urbanus pronus Pronus Longtail Urbanus esmeraldus Esmeralda Longtail Urbanus evona Turquoise Longtail Urbanus dorantes Dorantes Longtail Urbanus teleus Teleus Longtail Urbanus tanna Tanna Longtail Urbanus simplicius Plain Longtail Urbanus procne Brown Longtail -

Moth Tails Divert Bat Attack: Evolution of Acoustic Deflection

Moth tails divert bat attack: Evolution of acoustic deflection Jesse R. Barbera,1, Brian C. Leavella, Adam L. Keenera, Jesse W. Breinholtb, Brad A. Chadwellc, Christopher J. W. McClurea,d, Geena M. Hillb, and Akito Y. Kawaharab,1 aDepartment of Biological Sciences, Boise State University, Boise, ID 83725; bFlorida Museum of Natural History, McGuire Center for Lepidoptera and Biodiversity, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL 32611; cDepartment of Anatomy and Neurobiology, Northeast Ohio Medical University, Rootstown, OH 44272; and dPeregrine Fund, Boise, ID 83709 Edited by May R. Berenbaum, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Urbana, IL, and approved January 28, 2015 (received for review November 15, 2014) Adaptations to divert the attacks of visually guided predators the individuals that were tested. Interactions took place under have evolved repeatedly in animals. Using high-speed infrared darkness in a sound-attenuated flight room. We recorded each videography, we show that luna moths (Actias luna) generate an engagement with infrared-sensitive high-speed cameras and ul- acoustic diversion with spinning hindwing tails to deflect echolo- trasonic microphones. To constrain the moths’ flight to a ∼1m2 cating bat attacks away from their body and toward these non- area surveyed by the high-speed cameras, we tethered luna moths essential appendages. We pit luna moths against big brown bats from the ceiling with a monofilament line. (Eptesicus fuscus) and demonstrate a survival advantage of ∼47% for moths with tails versus those that had their tails removed. The Results and Discussion benefit of hindwing tails is equivalent to the advantage conferred Bats captured 34.5% (number of moths presented; n = 87) of to moths by bat-detecting ears. -

Wildlife in Your Young Forest.Pdf

WILDLIFE IN YOUR Young Forest 1 More Wildlife in Your Woods CREATE YOUNG FOREST AND ENJOY THE WILDLIFE IT ATTRACTS WHEN TO EXPECT DIFFERENT ANIMALS his guide presents some of the wildlife you may used to describe this dense, food-rich habitat are thickets, T see using your young forest as it grows following a shrublands, and early successional habitat. timber harvest or other management practice. As development has covered many acres, and as young The following lists focus on areas inhabited by the woodlands have matured to become older forest, the New England cottontail (Sylvilagus transitionalis), a rare amount of young forest available to wildlife has dwindled. native rabbit that lives in parts of New York east of the Having diverse wildlife requires having diverse habitats on Hudson River, and in parts of Connecticut, Rhode Island, the land, including some young forest. Massachusetts, southern New Hampshire, and southern Maine. In this region, conservationists and landowners In nature, young forest is created by floods, wildfires, storms, are carrying out projects to create the young forest and and beavers’ dam-building and feeding. To protect lives and shrubland that New England cottontails need to survive. property, we suppress floods, fires, and beaver activities. Such projects also help many other kinds of wildlife that Fortunately, we can use habitat management practices, use the same habitat. such as timber harvests, to mimic natural disturbance events and grow young forest in places where it will do the most Young forest provides abundant food and cover for insects, good. These habitat projects boost the amount of food reptiles, amphibians, birds, and mammals. -

Polyphemus Moth Antheraea Polyphemus (Cramer) (Insecta: Lepidoptera: Saturniidae: Saturniinae)1 Donald W

EENY-531 Polyphemus Moth Antheraea polyphemus (Cramer) (Insecta: Lepidoptera: Saturniidae: Saturniinae)1 Donald W. Hall2 Introduction Distribution The polyphemus moth, Antheraea polyphemus (Cramer), Polyphemus moths are our most widely distributed large is one of our largest and most beautiful silk moths. It is silk moths. They are found from southern Canada down named after Polyphemus, the giant cyclops from Greek into Mexico and in all of the lower 48 states, except for mythology who had a single large, round eye in the middle Arizona and Nevada (Tuskes et al. 1996). of his forehead (Himmelman 2002). The name is because of the large eyespots in the middle of the moth is hind wings. Description The polyphemus moth also has been known by the genus name Telea, but it and the Old World species in the genus Adults Antheraea are not considered to be sufficiently different to The adult wingspan is 10 to 15 cm (approximately 4 to warrant different generic names. Because the name Anther- 6 inches) (Covell 2005). The upper surface of the wings aea has been used more often in the literature, Ferguson is various shades of reddish brown, gray, light brown, or (1972) recommended using that name rather than Telea yellow-brown with transparent eyespots. There is consider- to avoid confusion. Both genus names were published in able variation in color of the wings even in specimens from the same year. For a historical account of the polyphemus the same locality (Holland 1968). The large hind wing moth’s taxonomy see Ferguson (1972) or Tuskes et al. eyespots are ringed with prominent yellow, white (partial), (1996). -

Impacts and Options for Biodiversity-Oriented Land Managers

GYPSY MOTH (LYMANTRIA DISPAR): IMPACTS AND OPTIONS FOR BIODIVERSITY-ORIENTED LAND MANAGERS May 2004 NatureServe is a non-profit organization providing the scientific knowledge that forms the basis for effective conservation action. A NatureServe Technical Report Citation: Schweitzer, Dale F. 2004. Gypsy Moth (Lymantria dispar): Impacts and Options for Biodiversity- Oriented Land Managers. 59 pages. NatureServe: Arlington, Virginia. © 2004 NatureServe NatureServe 1101 Wilson Blvd., 15th Floor Arlington, VA 22209 www.natureserve.org Author’s Contact Information: Dr. Dale Schweitzer Terrestrial Invertebrate Zoologist NatureServe 1761 Main Street Port Norris, NJ 08349 856-785-2470 Email: [email protected] NatureServe Gypsy Moth: Impacts and Options for Biodiversity-Oriented Land Managers 2 Acknowledgments Richard Reardon (United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service Forest Health Technology Enterprise Team, Morgantown, WV), Kevin Thorpe (Agricultural Research Service, Insect Chemical Ecology Laboratory, Beltsville, MD) and William Carothers (Forest Service Forest Protection, Asheville, NC) for technical review. Sandra Fosbroke (Forest Service Information Management Group, Morgantown, WV) provided many helpful editorial comments. The author also wishes to commend the Forest Service for funding so much important research and technology development into the impacts of gypsy moth and its control on non-target organisms and for encouraging development of more benign control technologies like Gypchek. Many, but by no means all, Forest Service-funded studies are cited in this document, including Peacock et al. (1998), Wagner et al. (1996), and many of the studies cited from Linda Butler and Ann Hajek. Many other studies in the late 1980s and 1990s had USDA Forest Service funding from the Appalachian Gypsy Moth Integrated Pest Management Project (AIPM). -

Moth Fun Facts

MOTH FUN FACTS NC has 174 species of butterflies, and 2,000-2,500 moths! That’s 11 to 14 times as many moth spe- cies as there are butterflies. There is moth caterpillar that is carnivorous, the Ashen Pinion, Lithophane antennata which is a well-known predator of winter moths. Some tiger moths in the family Arctiidae are known to "jam" bat echolocation by producing sounds. The North Carolina Heritage Program lists 99 state concern moths mostly from the mountains, sandhills and coast. Many females of the Tussock family of moths don't have wings. The Hawk moth (Sphinx) is the worlds fastest flying insect attaining speed of over 50 kph Moth antennae are either feather like or a hair like filament. The Cecropia moth is North America's largest insect with a six inch wingspan. Moths have hairy bodies to help retain internal body temperature necessary for flight. Quite a few moths fly during the day, such as the Hummingbird Clearwing, Virginia Ctenucha and the Spear-Marked Black. In colder climates some moths can have a two year life cycle. Some moth caterpillars, such as the "Io" are covered with stinging hairs. Moths make up 80 percent of the order lepidoptera. A small group of moths are called "Bird Dropping" moths because -you guessed it- that's what they resemble when they are at rest. Moths navigate by two methods. They use the moon and stars when available and geomagnetic clues when light sources are obscured. Cloth Moths eat such things as wool, fur and other animal products. -

Good Water Ripples Volume 8 Number 5

GoodGood WaterWater RipplesRipples Vol. 8 • No. 5 | Oct/Nov 2019 For information contact: http://txmn.org/goodwater or goodwatermn2@gmailcom Lori Franz, Editor • Holly Zeiner, Layout/Design In Search of Swamp Rabbit and other Species of Greatest Conservation Need By Mike Farley Sylvilagus aquaticus was observed in more efficient lookout during a vulnera- Armadillo, and Virginia Opossum was Williamson County early this year and ble moment. observed. We began using scents for throughout the year before at Berry attracting mammals to an ideal location Springs Park and Preserve, as well as In those six weeks there have been within camera view. We experimented North San Gabriel River - captured or seven observations of Bobcat all over the with food, vegetables and seeds, but observed by trail 35-acre south plot quickly abandoned this since it always camera and digital where we began drew numerous raccoons and fighting. camera. The county our search. Anoth- The scents now used are pure vanilla is on the westernmost er recent observa- extract, imitation vanilla, and apple cider edge of its range, tion was the Gray spray. with swamp rabbits Fox on the North being more common San Gabriel with Favorable camera locations include in east Texas and a rabbit clutched grasses, such as Inland Sea Oats, Vir- southeastern U.S. in its mouth and ginia Wild Rye, greenbriers, and dew- making its way berry. Dense thicket near water is the Swamp Rabbit is a back to a nearby rabbit’s preferred cover habitat, with a real animal and not den. All of this fast zig-zagging escape from predators. -

Impacts of Native and Non-Native Plants on Urban Insect Communities: Are Native Plants Better Than Non-Natives?

Impacts of Native and Non-native plants on Urban Insect Communities: Are Native Plants Better than Non-natives? by Carl Scott Clem A thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Auburn University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Science Auburn, Alabama December 12, 2015 Key Words: native plants, non-native plants, caterpillars, natural enemies, associational interactions, congeneric plants Copyright 2015 by Carl Scott Clem Approved by David Held, Chair, Associate Professor: Department of Entomology and Plant Pathology Charles Ray, Research Fellow: Department of Entomology and Plant Pathology Debbie Folkerts, Assistant Professor: Department of Biological Sciences Robert Boyd, Professor: Department of Biological Sciences Abstract With continued suburban expansion in the southeastern United States, it is increasingly important to understand urbanization and its impacts on sustainability and natural ecosystems. Expansion of suburbia is often coupled with replacement of native plants by alien ornamental plants such as crepe myrtle, Bradford pear, and Japanese maple. Two projects were conducted for this thesis. The purpose of the first project (Chapter 2) was to conduct an analysis of existing larval Lepidoptera and Symphyta hostplant records in the southeastern United States, comparing their species richness on common native and alien woody plants. We found that, in most cases, native plants support more species of eruciform larvae compared to aliens. Alien congener plant species (those in the same genus as native species) supported more species of larvae than alien, non-congeners. Most of the larvae that feed on alien plants are generalist species. However, most of the specialist species feeding on alien plants use congeners of native plants, providing evidence of a spillover, or false spillover, effect. -

Like a Moth to a Flower

Like a Moth to a Flower Moths After dark, moths, as well as bats, take over the pollinating night shift. Nocturnal bloomers, with pale or white flowers heavy with fragrance and copious nectar, attract these pollinators. Some moths are also active by day. Moths and Butterflies Butterflies, possibly the best loved of all insects, are appreciated as benign creatures that add color, beauty, and grace to our gardens. Moths, on the other hand, aren’t nearly as appreciated for their pollinating contributions. Butterflies and moths belong to the same insect order, Lepidoptera. Can you tell the difference between a moth and a butterfly? In general, butterflies are brightly colored, and fly by day, and moths are more likely to be grey or brown, and fly at night. But there are numerous exceptions: such as bee-mimicking hawkmoths, colorful luna moths, and colorful, day-flying scape moths. At rest, butterflies tend to hold their wings either partially open or closed vertically over their bodies (like the sails of tiny sail boats). Most moths, however, hold their wings flat. Moths tend to be fatter and hairier than butterflies. And moths’ antennae are often broad, complex and feathery, while butterflies generally have simple antennae with clubbed tips. Metamorphosis Like a butterfly, a moth begins life as an egg laid on or near its host plant. The egg hatches into a tiny caterpillar, eating and growing until it transforms into a chrysalis. They go through complete metamorphosis into sexually active, winged adults. Some moths spin a cocoon from their silk glands, creating an additional layer of protection. -

THE LIFESPAN of CHICKADEES a Thesis Submitted to Kent State

THE LIFESPAN OF CHICKADEES A thesis submitted To Kent State University in partial Fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Fine Arts by Marybeth E. Cieplinski May, 2014 © Copyright All rights reserved Except for previously published materials Thesis written by Marybeth E. Cieplinski B.A., Kent State University, 2010 M.F.A., Kent State University, 2014 Approved by David Giffels, Assistant Professor of English, NEOMFA, Masters Advisor Robert W. Trogdon, Ph.D., Chair, Department of English Raymond A. Craig, Ph.D., Associate Dean, College of Arts and Sciences TABLE OF CONTENTS...................................................................................................iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS..................................................................................................v MOVING ALONG AT THE SPEED OF . ....................................................... 1 THE LIFESPAN OF CHICKADEES.................................................................... 6 CONFESSIONS OF A WOULD-BE GARDENER............................................. 22 THE ACCIDENTAL CAT..................................................................................... 33 PENNSYLVANIA IN MY BLOOD.......................................................................51 BELLS! THE RIDE BEGINS................................................................................ 59 WISHES LIKE SHOOTING STARS..................................................................... 63 EMPTYING THE NEST........................................................................................ -

Master List for AR Revised

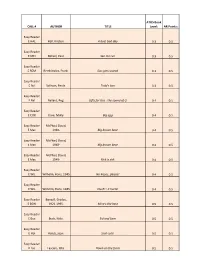

ATOS Book CALL # AUTHOR TITLE Level: AR Points: Easy Reader E HAL Hall, Kirsten. A bad, bad day 0.3 0.5 Easy Reader E MEI Meisel, Paul. See me run 0.3 0.5 Easy Reader E REM Remkiewicz, Frank. Gus gets scared 0.3 0.5 Easy Reader E Sul Sullivan, Paula. Todd's box 0.3 0.5 Easy Reader E Bal Ballard, Peg. Gifts for Gus : the sound of G 0.4 0.5 Easy Reader E COX Coxe, Molly. Big egg 0.4 0.5 Easy Reader McPhail, David, E Mac 1940- Big brown bear 0.4 0.5 Easy Reader McPhail, David, E Mac 1940- Big brown bear 0.4 0.5 Easy Reader McPhail, David, E Mac 1940- Rick is sick 0.4 0.5 Easy Reader E WIL Wilhelm, Hans, 1945- No kisses, please! 0.4 0.5 Easy Reader E WIL Wilhelm, Hans, 1945- Ouch! : it hurts! 0.4 0.5 Easy Reader Bonsall, Crosby, E BON 1921-1995. Mine's the best 0.5 0.5 Easy Reader E Buc Buck, Nola. Sid and Sam 0.5 0.5 Easy Reader E Hol Holub, Joan. Scat cats! 0.5 0.5 Easy Reader E Las Lascaro, Rita. Down on the farm 0.5 0.5 Easy Reader E Mor Moran, Alex. Popcorn 0.5 0.5 Easy Reader E Tri Trimble, Patti. What day is it? 0.5 0.5 Easy Reader E Wei Weiss, Ellen, 1949- Twins in the park 0.5 0.5 Easy Reader E Kli Amoroso, Cynthia. -

Parc National Du Mont-Mégantic

PARC NATIONAL DU MONT-MÉGANTIC DISCOVERY GUIDE WELCOME TO THE PARK A nature-experience of international calibre at the heart of the first Dark Sky Reserve in the world! LUNA MOTH A unique shape, intense climate and amazing star-filled sky all come together to make Parc national du Mont-Mégantic an exceptional site. With its beautiful emerald wings and It’s a place where a sense of vastness is ever present: in the forests and on feathery antennae, this flamboyant member the landscapes, and through time and space. Created to preserve an area of the Saturniidae family and the Park’s representative of border mountains, the park is characterized by numerous symbol, is undoubtedly one of the most vocations that help protect its exceptional ecosystems and is home to mountain flamboyant moths. The Luna Moth is usually trails, astronomical observatories, a museum and religious sanctuary. It also lies found in the trees of deciduous forests in at the heart of the first International Dark Sky Reserve whose pioneering work southern Québec and has a mysterious serves to protect an endangered natural heritage. A conservation mission that aversion to all forms of pollution and is extends from Earth to the Stars! vulnerable to light pollution. It reproduces We hope you enjoy your discoveries! shortly after cocoons hatch in mid-May. Since it lives only a few days, this nocturnal moth does not feed, and males die soon Discover more at sepaq.com/montmegantic after mating. Dogs are allowed at Parc national du SUPERVISED ACCESS Mont-Mégantic in certain designated All details at sepaq.com/animals FOR DOGS areas and over a defined period of time.