Oliver Cromwell: Man of Force Robert Ekkebus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

War of Roses: a House Divided

Stanford Model United Nations Conference 2014 War of Roses: A House Divided Chairs: Teo Lamiot, Gabrielle Rhoades Assistant Chair: Alyssa Liew Crisis Director: Sofia Filippa Table of Contents Letters from the Chairs………………………………………………………………… 2 Letter from the Crisis Director………………………………………………………… 4 Introduction to the Committee…………………………………………………………. 5 History and Context……………………………………………………………………. 5 Characters……………………………………………………………………………….. 7 Topics on General Conference Agenda…………………………………..……………. 9 Family Tree ………………………………………………………………..……………. 12 Special Committee Rules……………………………………………………………….. 13 Bibliography……………………………………………………………………………. 14 Letters from the Chairs Dear Delegates, My name is Gabrielle Rhoades, and it is my distinct pleasure to welcome you to the Stanford Model United Nations Conference (SMUNC) 2014 as members of the The Wars of the Roses: A House Divided Joint Crisis Committee! As your Wars of the Roses chairs, Teo Lamiot and I have been working hard with our crisis director, Sofia Filippa, and SMUNC Secretariat members to make this conference the best yet. If you have attended SMUNC before, I promise that this year will be even more full of surprise and intrigue than your last conference; if you are a newcomer, let me warn you of how intensely fun and challenging this conference will assuredly be. Regardless of how you arrive, you will all leave better delegates and hopefully with a reinvigorated love for Model UN. My own love for Model United Nations began when I co-chaired a committee for SMUNC (The Arab Spring), which was one of my very first experiences as a member of the Society for International Affairs at Stanford (the umbrella organization for the MUN team), and I thoroughly enjoyed it. Later that year, I joined the intercollegiate Model United Nations team. -

Paper 2: Power: Monarchy and Democracy in Britain C1000-2014

Paper 2: Power: Monarchy and democracy in Britain c1000-2014. 1. Describe the Anglo-Saxon system of government. [4] • Witan –The relatives of the King, the important nobles (Earls) and churchmen (Bishops) made up the Kings council which was known as the WITAN. These men led the armies and ruled the shires on behalf of the king. In return, they received wealth, status and land. • At local level the lesser nobles (THEGNS) carried out the roles of bailiffs and estate management. Each shire was divided into HUNDREDS. These districts had their own law courts and army. • The Church handled many administrative roles for the King because many churchmen could read and write. The Church taught the ordinary people about why they should support the king and influence his reputation. They also wrote down the history of the period. 2. Explain why the Church was important in Anglo-Saxon England. [8] • The church was flourishing in Aethelred’s time (c.1000). Kings and noblemen gave the church gifts of land and money. The great MINSTERS were in Rochester, York, London, Canterbury and Winchester. These Churches were built with donations by the King. • Nobles provided money for churches to be built on their land as a great show of status and power. This reminded the local population of who was in charge. It hosted community events as well as religious services, and new laws or taxes would be announced there. Building a church was the first step in building a community in the area. • As churchmen were literate some of the great works of learning, art and culture. -

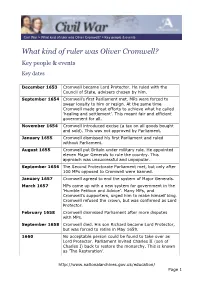

What Kind of Ruler Was Oliver Cromwell? > Key People & Events

Civil War > What kind of ruler was Oliver Cromwell? > Key people & events What kind of ruler was Oliver Cromwell? Key people & events Key dates December 1653 Cromwell became Lord Protector. He ruled with the Council of State, advisers chosen by him. September 1654 Cromwell’s first Parliament met. MPs were forced to swear loyalty to him or resign. At the same time Cromwell made great efforts to achieve what he called ‘healing and settlement’. This meant fair and efficient government for all. November 1654 Cromwell introduced excise (a tax on all goods bought and sold). This was not approved by Parliament. January 1655 Cromwell dismissed his first Parliament and ruled without Parliament. August 1655 Cromwell put Britain under military rule. He appointed eleven Major Generals to rule the country. This approach was unsuccessful and unpopular. September 1656 The Second Protectorate Parliament met, but only after 100 MPs opposed to Cromwell were banned. January 1657 Cromwell agreed to end the system of Major Generals. March 1657 MPs came up with a new system for government in the ‘Humble Petition and Advice’. Many MPs, and Cromwell’s supporters, urged him to make himself king. Cromwell refused the crown, but was confirmed as Lord Protector. February 1658 Cromwell dismissed Parliament after more disputes with MPs. September 1658 Cromwell died. His son Richard became Lord Protector, but was forced to retire in May 1659. 1660 No acceptable person could be found to take over as Lord Protector. Parliament invited Charles II (son of Charles I) back to restore the monarchy. This is known as ‘The Restoration’. -

Notes on Political Poems Ca. 1640

Studies in English Volume 1 Article 13 1960 Notes on Political Poems ca. 1640 Charles L. Hamilton University of Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/ms_studies_eng Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Recommended Citation Hamilton, Charles L. (1960) "Notes on Political Poems ca. 1640," Studies in English: Vol. 1 , Article 13. Available at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/ms_studies_eng/vol1/iss1/13 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the English at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studies in English by an authorized editor of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Hamilton: Notes on Political Poems Notes on Political Poems, c. 1640 Charles L. Hamilton HET CIVILwars in England and Scotland during the seventeenth century produced a wealth of popular literature. Some of it has permanent literary merit, but a large share of the popular creations, especially of the poetry, was little more than bad doggerel. Even so, one little-known and two unpublished poems such as the following are important as a guide to public opinion. From the period of the Bishops’ Wars (1638-40) the Scottish Covenanters repeatedly urged the English to abolish episcopacy and to enter a religious union with them.1 The following poem, written very likely on the eve of the meeting of the Long Parliament, exem plifies the Scottish feeling very clearly: Oyes, Oyes do I Cry The Bishops’ Bridles Will ye Buy2 Since Bishops first began to ride, In state so near the crown They have been aye puffed up with pride And ride with great renown. -

POLITICS, SOCIETY and CIVIL WAR in WARWICKSHIRE, 162.0-1660 Cambridge Studies in Early Modern British History

Cambridge Studies in Early Modern British History POLITICS, SOCIETY AND CIVIL WAR IN WARWICKSHIRE, 162.0-1660 Cambridge Studies in Early Modern British History Series editors ANTHONY FLETCHER Professor of History, University of Durham JOHN GUY Reader in British History, University of Bristol and JOHN MORRILL Lecturer in History, University of Cambridge, and Fellow and Tutor of Selwyn College This is a new series of monographs and studies covering many aspects of the history of the British Isles between the late fifteenth century and the early eighteenth century. It will include the work of established scholars and pioneering work by a new generation of scholars. It will include both reviews and revisions of major topics and books which open up new historical terrain or which reveal startling new perspectives on familiar subjects. It is envisaged that all the volumes will set detailed research into broader perspectives and the books are intended for the use of students as well as of their teachers. Titles in the series The Common Peace: Participation and the Criminal Law in Seventeenth-Century England CYNTHIA B. HERRUP Politics, Society and Civil War in Warwickshire, 1620—1660 ANN HUGHES London Crowds in the Reign of Charles II: Propaganda and Politics from the Restoration to the Exclusion Crisis TIM HARRIS Criticism and Compliment: The Politics of Literature in the Reign of Charles I KEVIN SHARPE Central Government and the Localities: Hampshire 1649-1689 ANDREW COLEBY POLITICS, SOCIETY AND CIVIL WAR IN WARWICKSHIRE, i620-1660 ANN HUGHES Lecturer in History, University of Manchester The right of the University of Cambridge to print and sell all manner of books was granted by Henry VIII in 1534. -

Oliver Cromwell, Memory and the Dislocations of Ireland Sarah

CHAPTER EIGHT ‘THE ODIOUS DEMON FROM ACROSS THE sea’. OLIVER CROMWELL, MEMORY AND THE DISLOCATIONS OF IRELAND Sarah Covington As with any country subject to colonisation, partition, and dispossession, Ireland harbours a long social memory containing many villains, though none so overwhelmingly enduring—indeed, so historically overriding—as Oliver Cromwell. Invading the country in 1649 with his New Model Army in order to reassert control over an ongoing Catholic rebellion-turned roy- alist threat, Cromwell was in charge when thousands were killed during the storming of the towns of Drogheda and Wexford, before he proceeded on to a sometimes-brutal campaign in which the rest of the country was eventually subdued, despite considerable resistance in the next few years. Though Cromwell would himself depart Ireland after forty weeks, turn- ing command over to his lieutenant Henry Ireton in the spring of 1650, the fruits of his efforts in Ireland resulted in famine, plague, the violence of continued guerrilla war, ethnic cleansing, and deportation; hundreds of thousands died from the war and its aftermath, and all would be affected by a settlement that would, in the words of one recent historian, bring about ‘the most epic and monumental transformation of Irish life, prop- erty, and landscape that the island had ever known’.1 Though Cromwell’s invasion generated a significant amount of interna- tional press and attention at the time,2 scholars have argued that Cromwell as an embodiment of English violence and perfidy is a relatively recent phenomenon in Irish historical memory, having emerged only as the result of nineteenth-century nationalist (or unionist) movements which 1 William J. -

John Darby and the Whig Canon

JOHN DARBY AND THE WHIG CANON I A celebrated series of books by the English commonwealthmen of the seventeenth century was published between 1698 and 1700. The series included major editions of works by John Milton, Algernon Sidney, and James Harrington, and the civil war memoirs of Edmund Ludlow, Denzil Holles, John Berkeley, and Thomas Fairfax. Collectively these texts have become known as the ‘whig canon’.1 Over the following century this set of writings would profoundly shape the development of republican thought on both sides of the Atlantic.2 The texts of the whig canon would be cited approvingly by thinkers as diverse as Bolingbroke and the founding fathers of the American constitution.3 At their original moment of publication, however, the series was designed to bolster opposition to the consolidation of power by the court whigs under William III. By reasserting ‘true whig’ principles against the corruption of the apostates who made their peace with the court, these historic works were made to chime with the political challenges faced by the opposition in the present moment: attacking the maintenance of standing armies by the state, inveighing against priestcraft, and asserting the primacy of the ancient constitution. 1 Caroline Robbins, The eighteenth-century commonwealthman (Cambridge, MA, 1959), p. 32. 2 J. G. A. Pocock, ‘The varieties of whiggism from exclusion to reform: a history of ideology and discourse’, in Virtue, commerce, and history: essays on political thought and history, chiefly in the eighteenth century (Cambridge, 1985), pp. 215-310; Robbins, Commonwealthman; Blair Worden, Roundhead reputations: the English civil wars and the passions of posterity (London, 2001); Alan Craig Houston, Algernon Sidney and the republican heritage in England and America (Princeton, 1991). -

Oliver Cromwell and the Regicides

OLIVER CROMWELL AND THE REGICIDES By Dr Patrick Little The revengers’ tragedy known as the Restoration can be seen as a drama in four acts. The first, third and fourth acts were in the form of executions of those held responsible for the ‘regicide’ – the killing of King Charles I on 30 January 1649. Through October 1660 ten regicides were hanged, drawn and quartered, including Charles I’s prosecutor, John Cooke, republicans such as Thomas Scot, and religious radicals such as Thomas Harrison. In April 1662 three more regicides, recently kidnapped in the Low Countries, were also dragged to Tower Hill: John Okey, Miles Corbett and John Barkstead. And in June 1662 parliament finally got its way when the arch-republican (but not strictly a regicide, as he refused to be involved in the trial of the king) Sir Henry Vane the younger was also executed. In this paper I shall consider the careers of three of these regicides, one each from these three sets of executions: Thomas Harrison, John Okey and Sir Henry Vane. What united these men was not their political views – as we shall see, they differed greatly in that respect – but their close association with the concept of the ‘Good Old Cause’ and their close friendship with the most controversial regicide of them all: Oliver Cromwell. The Good Old Cause was a rallying cry rather than a political theory, embodying the idea that the civil wars and the revolution were in pursuit of religious and civil liberty, and that they had been sanctioned – and victory obtained – by God. -

Oliver Cromwell and the Siege of Drogheda

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Undergraduate Theses and Professional Papers 2017 Just Warfare, or Genocide?: Oliver Cromwell and the Siege of Drogheda Lukas Dregne Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/utpp Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Dregne, Lukas, "Just Warfare, or Genocide?: Oliver Cromwell and the Siege of Drogheda" (2017). Undergraduate Theses and Professional Papers. 175. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/utpp/175 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Theses and Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Dregne Just Warfare, or Genocide? Just Warfare, or Genocide?: Oliver Cromwell and the Siege of Drogheda." Sir, the state, in choosing men to serve it, takes no notice of their opinions; if they be willing to serve it, that satisfies. I advised you formerly to bear with minds of different men from yourself. Take heed of being sharp against those to whom you can object little but that they square not with you in matters of religion. - Cromwell, To Major General Crawford (1643) Lukas Dregne B.A., History, Political Science University of Montana 1 Dregne Just Warfare, or Genocide? Abstract: Oliver Cromwell has always been a subject of fierce debate since his death on September 3, 1658. The most notorious stain blotting his reputation occurred during the conquest of Ireland by forces of the English Parliament under his command. -

Cromwell Study Guide for the Film of 1970

1 Cromwell Study Guide for the Film of 1970 Dr. Ron Fritze’s Tudor and Stuart Britain Course At Athens State University, Fall 2011 Semester Cromwell starring Richard Harris dramatized the role of Oliver Cromwell in the English Civil War, including his participation in the trial and execution of King Charles I. Unlike the Tudors, the Stuart dynasty has not attracted much cinematic interest, except for the playboy King Charles II in a minor way. It is important for Americans to understand that the English Civil War looms in the popular consciousness of the British people in much the same way as the American Civil War remains alive in the popular consciousness of Americans. Just as we have people who continue to debate the rights and the wrongs of the American Civil War, the British have people who debate the rights and wrongs of their civil war as well. We have re-enactors, they have re-enactors. The film treats the historical Oliver Cromwell sympathetically. Not all British and Irish would agree that he should be treated that way. In fact, Cromwell is the most hated figure in the Irish historical imagination. To prepare for viewing this film, take at look at the Wikipedia article on the film Cromwell. The article includes a list of some of the film’s historical inaccuracies. As you study this film, you should research and answer the questions below. They will help you write your compare-and-contrast paper. You will also find that the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography and the Historical Dictionary of Stuart England will help you with your background research. -

Christmas Is Cancelled! What Were Cromwell’S Main Political and Religious Aims for the Commonwealth 1650- 1660?

The National Archives Education Service Christmas is Cancelled! What were Cromwell’s main political and religious aims for the Commonwealth 1650- 1660? Cromwell standing in State as shown in Cromwelliana Christmas is Cancelled! What were Cromwell’s main political and religious aims? Contents Background 3 Teacher’s notes 4 Curriculum Connections 5 Source List 5 Tasks 6 Source 1 7 Source 2 9 Source 3 10 Source 4 11 Source 5 12 Source 6 13 Source 7 14 Source 8 15 Source 9 16 This resource was produced using documents from the collections of The National Archives. It can be freely modified and reproduced for use in the classroom only. 2 Christmas is Cancelled! What were Cromwell’s main political and religious aims? Background On 30 January 1649 Charles I the King of England was executed. Since 1642 civil war had raged in England, Scotland and Ireland and men on opposite sides (Royalists and Parliamentarians) fought in battles and sieges that claimed the lives of many. Charles I was viewed by some to be the man responsible for the bloodshed and therefore could not be trusted on the throne any longer. A trial resulted in a guilty verdict and he was executed outside Banqueting House in Whitehall. During the wars Oliver Cromwell had risen amongst Army ranks and he led the successful New Model Army which had helped to secure Parliament’s eventual victory. Cromwell also achieved widespread political influence and was a high profile supporter of the trial and execution of the King. After the King’s execution England remained politically instable. -

A Study in Regicide . an Analysis of the Backgrounds and Opinions of the Twenty-Two Survivors of the '

A study in regicide; an analysis of the backgrounds and opinions of the twenty- two survivors of the High court of Justice Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Kalish, Edward Melvyn, 1940- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 27/09/2021 14:22:32 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/318928 A STUDY IN REGICIDE . AN ANALYSIS OF THE BACKGROUNDS AND OPINIONS OF THE TWENTY-TWO SURVIVORS OF THE ' •: ; ■ HIGH COURT OF JUSTICE >' ' . by ' ' ■ Edward Ho Kalish A Thesis Submittedto the Faculty' of 'the DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY ' ' In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of : MASTER OF ARTS .In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 1 9 6 3 STATEMENT:BY AUTHOR / This thesishas been submitted in partial fulfill ment of requirements for an advanced degree at The - University of Arizona and is deposited in The University Library to be made available to borrowers under rules of the Library« Brief quotations from this thesis are allowable without special permission, provided that accurate acknowedg- ment. of source is madeRequests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this manuscript in whole or in part may be granted by the head of the major department .or the Dean of the Graduate<College-when in their judgment the proposed use of the material is in the interests of scholarship«' ' In aliiotdiefV instanceshowever, permission .