Citgo Sign in Kenmore Square Study Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

May 8, 2016 Ascension of the Lord Page 6

Cathedral of St. John the Baptist 222 East Harris Street, Savannah, Georgia 31401 - Located at Abercorn and East Harris Streets Most Reverend Gregory J. Hartmayer OFM Conv.— Bishop of Savannah Most Reverend J. Kevin Boland — Bishop Emeritus Photo by Mary Clark Rechtiene Mass Schedule Faith Formation Children’s Religious Ed Sunday 8:45 am to 9:50 am Saturday: 12 Noon & 5:30 p.m. R. C. I. A. Tuesday 7:00 pm to 8:00pm Sunday: 8:00 am, 10:00 am, & 11:30 a.m. Latin Mass 1:00 p.m. Weekdays: Mon thru Fri: 7:30 am & 12 Noon Holy Days: 7:30 am, 12 Noon, 6:00 pm Parish Staff Nursery: 10:00am Masses on Sundays. Rector - Very Rev. J. Gerard Schreck, JCD In Residence - Msgr. William O’Neill, Rector Emeritus In Residence - Very Rev. Daniel F. Firmin, JCL, VG In Residence - Rev. Pablo Migone Baptisms Sacraments Permanent Deacon - Rev. Dr.. Dewain E. Smith, Ph.D. Arrangements should be made in advance. Sacristan - Lynne Everett, MD Confessions Director of Religious Education - Mrs. Janee Przybyl Saturday:11:00 am to 11:45 am & 4:15 pm to 5:00 pm Bookkeeper/Admin. Assistant - Ms. Jan Cunningham Also by request at other times. Office Assistant - Mrs. Brenda Price Weddings Music Director - Mr. McDowell Fogle, MM Arrangements should be made at least four months in Asst. Organist- Ms. Heidi Ordaz, MM advance. Participation in a marriage preparation Cantors - Rebecca Flaherty and Jillian Pashke Durant program is required. Please call parish office for more Maintenance - Mr. Jimmy Joseph Sheehan III information. -

11 Beacon Street

Orient Heights 38 28 TOBIN BRIDGE Sullivan Square 93 Wood Island 28 1 Airport Community College 28 Lechmere Maverick Airport Terminal C 93 1 AMENITIES LOGAN AIRPORT Science Park North Station Central • Lobby Attendant BEACONAirport TerminalSTREET A • Professional property management 11 • Convenient to public transportation, including commuter rail at South Station, and the Red, Green & PLUG & PLAY OPPORTUNITY | 4,00690 SF SUBLEASE | BOSTON, MA Orange T Lines at Downtown Crossing Airport Terminal B2 Kendall/MIT • Steps to several parking garages and area amenities including the XV Beacon and Omni Parker House Hotels, Boston Sports and Beacon HaymarketHill Athletic Club, Boston Common Park, CVS, Super Walgreens, Airport Terminal B1 Charles/MGHStarbucks, Moo, Number 9 Park and Carrie Nation Restaurants and a wide variety of other eateries LONGELLOW BRIDGE Bowdoin Government Center Aquarium State St y a w n e MASSACHUSETTS e r G INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY 3 y d 11 BEACON ST e Park St n n e K MASS AVE BRIDGE e s Boston Downtown o Commons Crossing R NORTHERN AVE BRIDGE Public EVELYN MOAKLEY BRIDGE Garden Boylston South Station Court House Arlington Chinatown Boston University West 90 Copley Boston University East Boston University Central 20 Tufts Medical Center Boston Realty Advisors is pleased to present 4,006 SF for sublease at 11 Beacon Street. Located near Boston¹s historic State House Blandford ST YAWKEY Kenmore Hynes Convention Ctr and Commons, this 150,457 square foot, 14-story office building is only steps away from countless amenities such as retail, dining, HYNES World Trade Center public transportation and parking. The property is owned and managed by Synergy Investments. -

Language Visibility, Language Rights and Language Policy

Language visibility, language rights and language policy. Findings by the Pan-South African Language Board on language rights complaints between 1997 and 2005 Theodorus du Plessis, University of the Free State, Bloomfontein, South Africa 1 INTRODUCTION The context of this paper is the changing face of the South African linguistic landscape. Two of the central discourses regarding this matter concern the “need for change”, on the one hand, and the “need for redress”, on the other. The need for change is reflected in the following quote from Sachs (1994:8): I think many people have failed to understand the full significance of the move from bilingualism to multilingualism. Bilingualism is relatively easy. It is everything times two and you can officialise everything and you can establish policies based on fluency in two languages for the whole country. Multilingualism is not bilingualism multiplied by five and a half. It does not mean that every road sign must be in 11 languages – we will not see the streets – and to give examples like that is to trivialise the deep content of multilingualism [own emphasis]. Essentially, the “need for change” involves a change from bilingual to multilingual. The pictures in Figure 1 illustrate this aspect of the changing linguistic landscape. The picture on the left was taken at the Mangaung Local Municipality in Bloemfontein, the central city of South Africa, while the one on the right was taken at the border between the Eastern Cape Province and the Northern Cape Province. The photograph on the left depicts a typical bilingual sign from the pre-1994 era, displaying Afrikaans and English. -

Dzhokhar Tsarnaev Had Murdered Krystle Marie Campbell, Lingzi Lu, Martin Richard, and Officer Sean Collier, He Was Here in This Courthouse

United States Court of Appeals For the First Circuit No. 16-6001 UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, Appellee, v. DZHOKHAR A. TSARNAEV, Defendant, Appellant. APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF MASSACHUSETTS [Hon. George A. O'Toole, Jr., U.S. District Judge] Before Torruella, Thompson, and Kayatta, Circuit Judges. Daniel Habib, with whom Deirdre D. von Dornum, David Patton, Mia Eisner-Grynberg, Anthony O'Rourke, Federal Defenders of New York, Inc., Clifford Gardner, Law Offices of Cliff Gardner, Gail K. Johnson, and Johnson & Klein, PLLC were on brief, for appellant. John Remington Graham on brief for James Feltzer, Ph.D., Mary Maxwell, Ph.D., LL.B., and Cesar Baruja, M.D., amici curiae. George H. Kendall, Squire Patton Boggs (US) LLP, Timothy P. O'Toole, and Miller & Chevalier on brief for Eight Distinguished Local Citizens, amici curiae. David A. Ruhnke, Ruhnke & Barrett, Megan Wall-Wolff, Wall- Wolff LLC, Michael J. Iacopino, Brennan Lenehan Iacopino & Hickey, Benjamin Silverman, and Law Office of Benjamin Silverman PLLC on brief for National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers, amicus curiae. William A. Glaser, Attorney, Appellate Section, Criminal Division, U.S. Department of Justice, with whom Andrew E. Lelling, United States Attorney, Nadine Pellegrini, Assistant United States Attorney, John C. Demers, Assistant Attorney General, National Security Division, John F. Palmer, Attorney, National Security Division, Brian A. Benczkowski, Assistant Attorney General, and Matthew S. Miner, Deputy Assistant Attorney General, were on brief, for appellee. July 31, 2020 THOMPSON, Circuit Judge. OVERVIEW Together with his older brother Tamerlan, Dzhokhar Tsarnaev detonated two homemade bombs at the 2013 Boston Marathon, thus committing one of the worst domestic terrorist attacks since the 9/11 atrocities.1 Radical jihadists bent on killing Americans, the duo caused battlefield-like carnage. -

Herald of Good TIDINGS

2016 Herald of Good TIDINGS “Get you up to a high mountain, O Zion, herald of good tidings; lift up your voice with strength, O Jerusalem, herald of good tidings, lift it up, fear not; say to the cities of Judah, ‘Behold your God!’” Isaiah 40:9 Fear of the Past Do you remember February 2015? Do you remember the shoveling? The snow? As I write this, another Nor’easter is predicted. All the anchor people on TV are bringing up February of last year. They say, “Here it is, the start of snow, it will be just like last year. Oh, woe is me, we are doomed let us all fall down on our face and wail in lamentation.” Well, maybe they do not SAY the last part, but from their tone of voice it is strongly implied. Winter is very annoying to a modern American. Winter makes us plan based on weather. If it snows, we might have to can- cel plans. If it snows, school will be cancelled. We will have to make plans to care for the kids. I planned to stay up north for three days in January, but the first night it fell to -13°F and I ran out of propane at 4 a.m. So I decided being home was better then freezing in a trailer or buying a ton of propane. It is good from time to time for weather, a good fill in for God, to change our schedule. When the weather is too bad it is good to ask, “Do we really need to do this?” That is a good question to ask often. -

UCLA-Bruin-Blue-Spring-2021.Pdf

BRUINS DESERVE MORE Earn an Extra $500 with Wescom!* Bank with Wescom and Get $500 on Us* To learn more and open your account, visit ucla.wescom.org/welcome. Promo Code: BRUIN 1-888-8WESCOM (1-888-893-7266) ® #BetterBankingforBruins /WescomCreditUnion @_Wescom Offer valid until 12/31/2021 and may discontinue at any time. Member must meet all qualifications to receive full $500 bonus. Full/partial bonus will be deposited to your regular savings account the first week of the month following the full calendar month after you qualify for the bonus. Offer valid for new members only and cannot be combined with any other offer. Youth Account, Wescom employees, their families, Wescom Volunteers, Wescom Board of Directors and existing Members are not eligible for this offer. Anyone who lives, works, worships, or attends school in Southern California is eligible to open an account at Wescom. A $1 deposit to a Regular Savings Account is required. Certain conditions and restrictions apply. Ask for further details. Insured by NCUA in California. And top 4 in the nation. #1 in Los Angeles, #4 in the nation, U.S. News & World Report Best Hospitals. BRUIN BLUE SPRING 2021 INSIDE this ISSUE VOL 7 | ISSUE 3 | SPRING 2021 THE OFFICIAL MAGAZINE OF CONTENTS UCLA ATHLETICS WRITERS: JON GOLD EMILY LERNER COURTNEY PERKES MANAGING EDITOR: DANNY HARRINGTON [email protected] 4 8 12 LAYOUT & DESIGN: 16 LEARFIELD IMG COLLEGE UCLA ATHLETICS IN PHOTOS SARAH JANE SNOWDEN, SPARKING A MOVEMENT Featuring UCLA men’s and women’s track and field teams, KIMBERLY SANDERS How Nia Dennis’ 90-second homage men’s water polo player Nicolas Saveljic and All-American to black culture became a viral sensation. -

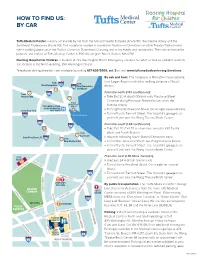

How to Find Us: by Car

HOW TO FIND US: BY CAR Tufts Medical Center is easily accessible by car from the Massachusetts Turnpike (Route 90), the Central Artery and the Southeast Expressway (Route 93). The hospital is located in downtown Boston—in Chinatown and the Theater District—and within walking distance of the Boston Common, Downtown Crossing and many hotels and restaurants. The main entrance for patients and visitors at Tufts Medical Center is 800 Washington Street, Boston, MA 02111. Floating Hospital for Children is located at 755 Washington Street. Emergency services for adult as well as pediatric patients are located at the North Building, 830 Washington Street. Telephone driving directions are available by calling 617-636-5000, ext. 5 or visit www.tuftsmedicalcenter.org/directions. By cab and train: The hospital is a 15-to-20-minute cab ride from Logan Airport and within walking distance of South from from New Hampshire 93 95 New Hampshire Station. 128 and Maine 2 From the north (I-93 southbound): from 95 Western MA » 1 Take Exit 20 A (South Station) onto Purchase Street. Continue along Purchase Street (this becomes the Logan International TUFTS MEDICAL CENTER Airport Surface Artery). & FLOATING HOSPITAL from New York FOR CHILDREN » Turn right onto Kneeland Street. Go straight several blocks. » Turn left onto Tremont Street. The hospital’s garage is on 90 Boston Harbor your left, just past the Wang Theatre/Boch Center. 95 From the south (I-93 northbound): 93 128 » Take Exit 20 (Exit 20 is a two-lane ramp for I-90 East & from West, and South Station). 3 Cape Cod from Providence, RI » Stay left, following South Station/Chinatown signs. -

Volume 127, Number 50 Cambridge, Massachusetts 02139 Tuesday, October 30, 2007 City Councillors Seek New 2-Year Terms in Cambridge Elections by Marie Y

Red Sox Win World Series—Championship Parade Today at Noon The Weather MIT’s Today: Sunny, 60°F (16°C) Tonight: Clear, 47°F (8°C) Oldest and Largest Tomorrow: Sunny and brisk, Newspaper 65°F (18°C) Details, Page 2 Volume 127, Number 50 Cambridge, Massachusetts 02139 Tuesday, October 30, 2007 City Councillors Seek New 2-Year Terms in Cambridge Elections By Marie Y. Thibault first-time candidate, says she is liv- STAFF WRITER ing with a disability and that her top Next Tuesday, Nov. 3, voters will priority is to bring Cambridge into decide who will sit on the Cam- compliance with the Americans with bridge City Council for the next two Disabilities Act. Jonathan Janik said years. There will be at least one new that synchronizing traffic signals in face, since only Cambridge would For more information about eight incumbents allow drivers to the election, including are running for re- get from one end interview responses from election. of the city to the candidates, see page 14. The main is- other more quick- sues this year are affordable housing, ly, so he has made it a top priority. education, and safety, as listed by The only current City Council SAMUEL KRonick—THE TECH many of the candidates as top priori- member who is not running for re- Berklee College of Music students Stash Wyslough (left) and Andy Reiner (right) celebrate the ties in their campaign. election is Anthony D. Galluccio, Red Sox World Series victory by jamming in the streets of Boston. See more photos on pages Some candidates are pushing who has just been elected to the Mas- 10–11. -

Boston Government Services Center: Lindemann-Hurley Preservation Report

BOSTON GOVERNMENT SERVICES CENTER: LINDEMANN-HURLEY PRESERVATION REPORT JANUARY 2020 Produced for the Massachusetts Division of Capital Asset Management and Maintenance (DCAMM) by Bruner/Cott & Associates Henry Moss, AIA, LEED AP Lawrence Cheng, AIA, LEED AP with OverUnder: 2016 text review and Stantec January 2020 Unattributed photographs in this report are by Bruner/Cott & Associates or are in the public domain. Table of Contents 01 Introduction & Context 02 Site Description 03 History & Significance 04 Preservation Narrative 05 Recommendations 06 Development Alternatives Appendices A Massachusetts Cultural Resource Record BOS.1618 (2016) B BSGC DOCOMOMO Long Fiche Architectural Forum, Photos of New England INTRODUCTION & CONTEXT 5 BGSC LINDEMANN-HURLEY PRESERVATION REPORT | DCAMM | BRUNER/COTT & ASSOCIATES WITH STANTEC WITH ASSOCIATES & BRUNER/COTT | DCAMM | REPORT PRESERVATION LINDEMANN-HURLEY BGSC Introduction This report examines the Boston Government Services Center (BGSC), which was built between 1964 and 1970. The purpose of this report is to provide an overview of the site’s architecture, its existing uses, and the buildings’ relationships to surrounding streets. It is to help the Commonwealth’s Division of Capital Asset Management and Maintenance (DCAMM) assess the significance of the historic architecture of the site as a whole and as it may vary among different buildings and their specific components. The BGSC is a major work by Paul Rudolph, one of the nation’s foremost post- World War II architects, with John Paul Carlhian of Shepley Bulfinch Richardson and Abbot. The site’s development followed its clearance as part of the city’s Urban Renewal initiative associated with creation of Government Center. A series of prior planning studies by I. -

Frutiger (Tipo De Letra) Portal De La Comunidad Actualidad Frutiger Es Una Familia Tipográfica

Iniciar sesión / crear cuenta Artículo Discusión Leer Editar Ver historial Buscar La Fundación Wikimedia está celebrando un referéndum para reunir más información [Ayúdanos traduciendo.] acerca del desarrollo y utilización de una característica optativa y personal de ocultamiento de imágenes. Aprende más y comparte tu punto de vista. Portada Frutiger (tipo de letra) Portal de la comunidad Actualidad Frutiger es una familia tipográfica. Su creador fue el diseñador Adrian Frutiger, suizo nacido en 1928, es uno de los Cambios recientes tipógrafos más prestigiosos del siglo XX. Páginas nuevas El nombre de Frutiger comprende una serie de tipos de letra ideados por el tipógrafo suizo Adrian Frutiger. La primera Página aleatoria Frutiger fue creada a partir del encargo que recibió el tipógrafo, en 1968. Se trataba de diseñar el proyecto de Ayuda señalización de un aeropuerto que se estaba construyendo, el aeropuerto Charles de Gaulle en París. Aunque se Donaciones trataba de una tipografía de palo seco, más tarde se fue ampliando y actualmente consta también de una Frutiger Notificar un error serif y modelos ornamentales de Frutiger. Imprimir/exportar 1 Crear un libro 2 Descargar como PDF 3 Versión para imprimir Contenido [ocultar] Herramientas 1 El nacimiento de un carácter tipográfico de señalización * Diseñador: Adrian Frutiger * Categoría:Palo seco(Thibaudeau, Lineal En otros idiomas 2 Análisis de la tipografía Frutiger (Novarese-DIN 16518) Humanista (Vox- Català 3 Tipos de Frutiger y familias ATypt) * Año: 1976 Deutsch 3.1 Frutiger (1976) -

Task Force Members Feel Left out As Northeastern Readies IMP Filing by Stephen Brophy on Campus

January WWW.FEnWAYNEWS.org 2013 FrEE serving the Fenway, Kenmore square, upper BacK Bay, prudential, longwood area & mission hill since 1974 volume 39, numBer 1 decemBer 27, 2012-JANUARY 31, 2013 Topping-off Moves Berklee Dorm Goal Closer task Force members Feel left out as northeastern readies IMP Filing BY STEPHEN BROPHY on campus. As a result they spread out and ortheastern University has been occupy a big proportion of rental apartments meeting with a task force of in the Fenway and Mission Hill. This not only representatives from the Fenway, drives up the rents in these neighborhoods, Mission Hill, and Lower Roxbury but it has also driven up overall property asN it prepares to file its new Institutional values, making it much more difficult to buy a Master Plan (IMP). The most recent meeting residential building on Mission Hill now than took place on December 20, and task force it was 15 or 20 years ago. members reportedly joined some city Councilor Mike Ross, who lives on councilors to express some dissatisfaction Mission Hill, criticized the school for the with the situation. many promises it has made to rectify this The IMP is part of the price institutions situation, promises that have not yet come pay for being located in Boston. The Boston to fruition. Councilor Jeff Sanchez, who Redevelopment Authority (BRA) requires represents part of the Back of the Hill section every university and hospital to file an of Mission Hill, joined Ross in this criticism. IMP outlining the institution’s plans for its Both argued that the university needs to physical plant for the next decade. -

Traffic Signs Manual

Traffic Signs Manual – Chapter 8 – Chapter Signs Manual Traffic Traffic Safety Measures and Signs for Road Works and Temporary Situations provides the official detailed guidance Traffic on these matters. Part 1: Design (ISBN 978-0-11-553051-7, price £70) is for those Signs responsible for the design of temporary traffic management arrangements needed to facilitate maintenance activities or in response to temporary situations. Manual CHAPTER Part 2: Operations is for those responsible for planning, managing and participating in operations to implement, 8 maintain and remove temporary traffic management arrangements. Part 3: Update 20 16 16 Pa rt 3: Update Traffic Safety Measures and Signs for Road Works and Temporary Situations Part 3: Update ISBN 978-0-11-553510-9 2016 www.tso.co.uk 9 780115 535109 10426 DFT TSM Chapter 8 New Edition v0_2.indd 1-3 22/02/2017 15:53 Published by TSO (The Stationery Office) and available from: Online www.tsoshop.co.uk Mail, Telephone, Fax & E-mail TSO PO Box 29, Norwich, NR3 1GN Telephone orders/General enquiries: 0870 600 5522 Fax orders: 0870 600 5533 E-mail: [email protected] Textphone 0870 240 3701 TSO@Blackwell and other Accredited Agents Customers can also order publications from: TSO Ireland 16 Arthur Street, Belfast BT1 4GD Tel 028 9023 8451 Fax 028 9023 5401 5755 TSM Vol2 V0_5.indd 1 9/2/09 16:33:36 Traffic Signs Manual Chapter 8 Traffic Safety Measures and Signs for Road Works and Temporary Situations Part 3: Update Department for Transport/Highways England Department for Infrastructure