Games, the New Lively Art

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Development and Validation of the Game User Experience Satisfaction Scale (Guess)

THE DEVELOPMENT AND VALIDATION OF THE GAME USER EXPERIENCE SATISFACTION SCALE (GUESS) A Dissertation by Mikki Hoang Phan Master of Arts, Wichita State University, 2012 Bachelor of Arts, Wichita State University, 2008 Submitted to the Department of Psychology and the faculty of the Graduate School of Wichita State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2015 © Copyright 2015 by Mikki Phan All Rights Reserved THE DEVELOPMENT AND VALIDATION OF THE GAME USER EXPERIENCE SATISFACTION SCALE (GUESS) The following faculty members have examined the final copy of this dissertation for form and content, and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy with a major in Psychology. _____________________________________ Barbara S. Chaparro, Committee Chair _____________________________________ Joseph Keebler, Committee Member _____________________________________ Jibo He, Committee Member _____________________________________ Darwin Dorr, Committee Member _____________________________________ Jodie Hertzog, Committee Member Accepted for the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences _____________________________________ Ronald Matson, Dean Accepted for the Graduate School _____________________________________ Abu S. Masud, Interim Dean iii DEDICATION To my parents for their love and support, and all that they have sacrificed so that my siblings and I can have a better future iv Video games open worlds. — Jon-Paul Dyson v ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Althea Gibson once said, “No matter what accomplishments you make, somebody helped you.” Thus, completing this long and winding Ph.D. journey would not have been possible without a village of support and help. While words could not adequately sum up how thankful I am, I would like to start off by thanking my dissertation chair and advisor, Dr. -

Videogames in the Museum: Participation, Possibility and Play in Curating Meaningful Visitor Experiences

Videogames in the museum: participation, possibility and play in curating meaningful visitor experiences Gregor White Lynn Parker This paper was presented at AAH 2016 - 42nd Annual Conference & Book fair, University of Edinburgh, 7-9 April 2016 White, G. & Love, L. (2016) ‘Videogames in the museum: participation, possibility and play in curating meaningful visitor experiences’, Paper presented at Association of Art Historians 2016 Annual Conference and Bookfair, Edinburgh, United Kingdom, 7-9 April 2016. Videogames in the Museum: Participation, possibility and play in curating meaningful visitor experiences. Professor Gregor White Head of School of Arts, Media and Computer Games, Abertay University, Dundee, UK Email: [email protected] Lynn Parker Programme Leader, Computer Arts, Abertay University, Dundee, UK Email: [email protected] Keywords Videogames, games design, curators, museums, exhibition, agency, participation, rules, play, possibility space, co-creation, meaning-making Abstract In 2014 Videogames in the Museum [1] engaged with creative practitioners, games designers, curators and museums professionals to debate and explore the challenges of collecting and exhibiting videogames and games design. Discussions around authorship in games and games development, the transformative effect of the gallery on the cultural reception and significance of videogames led to the exploration of participatory modes and playful experiences that might more effectively expose the designer’s intent and enhance the nature of our experience as visitors and players. In proposing a participatory mode for the exhibition of videogames this article suggests an approach to exhibition and event design that attempts to resolve tensions between traditions of passive consumption of curated collections and active participation in meaning making using theoretical models from games analysis and criticism and the conceit of game and museum spaces as analogous rules based environments. -

By Vince Shuley Born in a Burnaby Basement Three Decades Ago, British Columbia's Joystick Grip on the Global Video-Game Indust

BORN IN A BURNABY BASEMENT THREE DECADES AGO, BRITISH COLUMBIA’S JOYSTICK GRIP ON THE GLOBAL VIDEO-GAME INDUSTRY SEEMED UNTOUCHABLE. BUT FIERCE COMPETITION, BRAIN DRAINS AND THE FREEMIUM-FUELLED REALITIES OF THE NEW NETSCAPE HAVE BUMPED BC INTO THE BACKSEAT. FROM EA TO INDIE, WE CHRONICLE THE PROVINCE’S REMARKABLE ROLE IN THIS MAMMOTH DIGITAL BUSINESS AND FIND THAT THE GAME IS IN FACT, NOT OVER. Sember and Mattrick BY VINCE SHULEY when the subject of Canada’s greatest cultural but the foundations were laid by ambitious young Vancouverites. exports arises, video games are probably not the first thought that Two Burnaby schoolboys had the smarts and business sense comes to mind. However, more than music, television or film, to hatch Vancouver’s vibrant game industry 30 years ago. Don Canadian video games are bought and played by more people, in Mattrick and Jeff Sember began designing and selling digital com- more places, all over the world. Since the beginning of this medium, puter games out of their living rooms in the early 80s, and their Vancouver has sat at the center of video-game development and first published title, Evolution, was the first commercially successful innovation in the electronic world. From lone-ranger independents game ever made in Canada. After selling 400,000 copies, which paid (indies) to army-sized studios, video-game development companies for both their university tuitions, as well as a couple of shiny sports in Vancouver employ some of the most talented folks in the digital- cars, the teenagers formed Distinctive Software Incorporated (DSI) media industry. -

The First but Hopefully Not the Last: How the Last of Us Redefines the Survival Horror Video Game Genre

The College of Wooster Open Works Senior Independent Study Theses 2018 The First But Hopefully Not the Last: How The Last Of Us Redefines the Survival Horror Video Game Genre Joseph T. Gonzales The College of Wooster, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://openworks.wooster.edu/independentstudy Part of the Other Arts and Humanities Commons, and the Other Film and Media Studies Commons Recommended Citation Gonzales, Joseph T., "The First But Hopefully Not the Last: How The Last Of Us Redefines the Survival Horror Video Game Genre" (2018). Senior Independent Study Theses. Paper 8219. This Senior Independent Study Thesis Exemplar is brought to you by Open Works, a service of The College of Wooster Libraries. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Independent Study Theses by an authorized administrator of Open Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. © Copyright 2018 Joseph T. Gonzales THE FIRST BUT HOPEFULLY NOT THE LAST: HOW THE LAST OF US REDEFINES THE SURVIVAL HORROR VIDEO GAME GENRE by Joseph Gonzales An Independent Study Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Course Requirements for Senior Independent Study: The Department of Communication March 7, 2018 Advisor: Dr. Ahmet Atay ABSTRACT For this study, I applied generic criticism, which looks at how a text subverts and adheres to patterns and formats in its respective genre, to analyze how The Last of Us redefined the survival horror video game genre through its narrative. Although some tropes are present in the game and are necessary to stay tonally consistent to the genre, I argued that much of the focus of the game is shifted from the typical situational horror of the monsters and violence to the overall narrative, effective dialogue, strategic use of cinematic elements, and character development throughout the course of the game. -

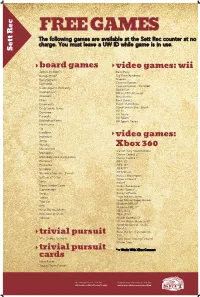

Sett Rec Counter at No Charge

FREE GAMES The following games are available at the Sett Rec counter at no charge. You must leave a UW ID while game is in use. Sett Rec board games video games: wii Apples to Apples Bash Party Backgammon Big Brain Academy Bananagrams Degree Buzzword Carnival Games Carnival Games - MiniGolf Cards Against Humanity Mario Kart Catchphrase MX vs ATV Untamed Checkers Ninja Reflex Chess Rock Band 2 Cineplexity Super Mario Bros. Crazy Snake Game Super Smash Bros. Brawl Wii Fit Dominoes Wii Music Eurorails Wii Sports Exploding Kittens Wii Sports Resort Finish Lines Go Headbanz Imperium video games: Jenga Malarky Mastermind Xbox 360 Call of Duty: World at War Monopoly Dance Central 2* Monopoly Deal (card game) Dance Central 3* Pictionary FIFA 15* Po-Ke-No FIFA 16* Scrabble FIFA 17* Scramble Squares - Parrots FIFA Street Forza 2 Motorsport Settlers of Catan Gears of War 2 Sorry Halo 4 Super Jumbo Cards Kinect Adventures* Superfection Kinect Sports* Swap Kung Fu Panda Taboo Lego Indiana Jones Toss Up Lego Marvel Super Heroes Madden NFL 09 Uno Madden NFL 17* What Do You Meme NBA 2K13 Win, Lose or Draw NBA 2K16* Yahtzee NCAA Football 09 NCAA March Madness 07 Need for Speed - Rivals Portal 2 Ruse the Art of Deception trivial pursuit SSX 90's, Genus, Genus 5 Tony Hawk Proving Ground Winter Stars* trivial pursuit * = Works With XBox Connect cards Harry Potter Young Players Edition Upcoming Events in The Sett Program your own event at The Sett union.wisc.edu/sett-events.aspx union.wisc.edu/eventservices.htm. -

The Case for Game Design Patterns

Gamasutra - Features - "A Case For Game Design Patterns" [03.13.02] 10/13/02 10:51 AM Gama Network Presents: The Case For Game Design Patterns By Bernd Kreimeier Gamasutra March 13, 2002 URL: http://www.gamasutra.com/features/20020313/kreimeier_01.htm Game design, like any other profession, requires a formal means to document, discuss, and plan. Over the past decades, the designer community could refer to a steadily growing body of past computer games for ideas and inspiration. Knowledge was also extracted from the analysis of board games and other classical games, and from the rigorous formal analysis found in mathematical game theory. However, while knowledge about computer games has grown rapidly, little progress has made to document our individual experiences and knowledge - documentation that is mandatory if the game design profession is to advance. Game design needs a shared vocabulary to name the objects and structures we are creating and shaping, and a set of rules to express how these building blocks fit together. This article proposes to adopt a pattern formalism for game design, based on the work of Christopher Alexander. Alexandrian patterns are simple collections of reusable solutions to solve recurring problems. Doug Church's "Formal Abstract Design Tools" [11] or Hal Barwood's "400 Design Rules" [6,7,18] have the same objective: to establish a formal means of describing, sharing and expanding knowledge about game design. From the very first interactive computer games, game designers have worked around this deficiency by relying on techniques and tools borrowed from other, older media -- predominantly tools for describing narrative media like cinematography, scriptwriting and storytelling. -

Art Games Applied to Disability

Figure 1. Thatgamecompany. PlayStation 3. (2009), Flower. Figure 2. Thatgamecompany. PlayStation 4. (2013), Flow. Esther Guanche Dorta. Phd student. [email protected] Ana Marqués Ibáñez. Teacher. [email protected] Department of Didactics of Plastic Expression. Faculty of Education. University of La Laguna. Tenerife. Art Games applied to disability. Figure 3. Thatgamecompany. PlayStation 3. (2012), Journey. THEME 4 – Technology – S3 DT Art Games, Disabilities, Design, Videogames, Inclusive education. Art Games applied to disability. Videogames are an emerging medium which represent a new form of artistic design, creating another means of expression for artists as well as different educational context adapted to people with dissabilities. Abstract This is a study of several examples of artistic videogames which can be 1. Art Games and Indie Games Concept The MOMA2 arranged an exhibition on the 50 years of videogame history, made a used to improve the quality of life of persons with impairment, for those review about the design and has added the most significant games to its permanent with specific or general motoric disabilities and mental disabilities in Art Game is an art object associated to the new interactive communications media exhibition, such as those of the Johnson Gallery with 14 videogames, which have order to bring them closer to art and design studies. As well as to develop new approaches in order to include this medium in artistic and a subgenre of the so-called serious videogames. The term was first used in been increased to around fifty. productions, study the impact of these images in Visual Culture and its academic circles in 2002, and referred to a videogame designed to boost artistic and construction by designing. -

Green Panels in the Ivory Towers

Panels in the Ivory Towers By Karen Green Friday November 6, 2009 09:00:00 am Our columnists are independent writers who choose subjects and write without editorial input from comiXology. The opinions expressed are the columnist's, and do not represent the opinion of comiXology. Last month, the eye, the arts magazine section of the Columbia Spectator (Columbia University's student paper since 1877), published an article on the graphic novels collection in Butler Library. The reporter—a tall, lanky, and enthusiastic fellow named Tommy Hill— interviewed Ben Katchor, Columbia professor Richard Bulliet, and me. It's a terrific piece of writing, engaging and thoughtful; you can read ithere. I was pretty chuffed when the piece came out, not least because it was so much better written even than I'd hoped (despite a sporadic use of "illustrator" for "artist" that may irk some). The true source of my delight, however, was in the approach the article had taken. When the article appeared in the eye, I had sent the link to a variety of family, friends and acquaintances, some in the comics biz, and one industry professional had replied, "Pow sock comics aren't for kids anymore!" At first I thought this was a gently humorous jab, but I eventually realized that this person had dismissed the article as yet another mainstream- press piece that marveled, "Golly gosh, look what's happened to comics; they're all grown 1 up!" Lord knows there are a lot of these CAFKA articles out there (hat tip for the acronym coinage to The Beat and its commenters), mostly written by people who are still stuck in some kind of Frederic Wertham mindlock, assuming that all comics are read by budding juvenile delinquents, even comics that win National Book Awards or special Pulitzer Prizes. -

The Art of Video Games @ Smithsonian

This page was exported from - Digital meets Culture Export date: Tue Sep 28 13:43:42 2021 / +0000 GMT The Art of Video Games @ Smithsonian The Smithsonian American Art Museum hosts a very special exhibition, to explore the forty-year evolution of video games as an artistic medium, with a focus on striking visual effects and the creative use of new technologies. An amalgam of traditional art forms ? painting, writing, sculpture, music, storytelling, cinematography ? video games are an increasingly expressive medium and offer artists a previously unprecedented method of communicating with and engaging audiences: in the forty years since the introduction of the first home video game, the field has attracted exceptional artistic talent. The exhibition features some of the most influential artists and designers during five eras of game technology, from early pioneers to contemporary designers, and is focused on the interplay of graphics, technology and storytelling through some of the best games for twenty gaming systems ranging from the Atari VCS to the PlayStation 3. Eighty games, selected with a poll by the public that replied enthusiastically - more than 3.7 million votes were cast by 119,000 people in 175 countries! - to the Smithsonian's call, demonstrate the evolution of the medium. The games are presented through still images and video footage. Five featured games, one from each era, show how players interact with diverse virtual worlds, highlighting innovative techniques that set the standard for many subsequent games. The playable games are Pac-Man, Super Mario Brothers, The Secret of Monkey Island, Myst, and Flower. Further the exhibition, there are video interviews with twenty developers and artists, large prints of in-game screen shots, and historic game consoles. -

Tion Thomas EA Graphics Lunch Presentation

Tion Thomas EA Graphics Lunch Presentation Software Engineering Intern Central Technology Group – Apt Purdue University – MS ‘09 Mentor: Anand Kelkar Manager: Fazeel Gareeboo EA Company Overview Founded in 1982 Largest 3rd party game publisher in the world Net revenue of $3.67 billion in FY 2008 #1 mobile game publisher (acquired JAMDAT) Multi-Platform philosophy Has/owns development studios all over the globe: Bioware/Pandemic (Bioshock, Mercenaries) Criterion (Burnout, Black) Digital Illusions (Battlefield series) Tiburon (Madden) Valve (Half-Life) Crytek (Crysis) EA Company Overview cont… 4 Major Brands/Divisions: EA Sports (FIFA, Madden, NBA, NFL, Tiger Woods, NASCAR) EA Sports Freestyle (NBA Street, NFL Street, FIFA Street, SSX) EA (Medal of Honor, C&C, Need For Speed, SIMS, Spore, Dead Space) POGO (Casual web based games) Currently has 4 entries on the top selling franchises of all time list: #3 - Sims (100 million) #5 - Need For Speed (80 million) #7 – Madden (70 million) #9 - FIFA (65 million) EA Is Unique Sheer size breaks the traditional game developer paradigm Bound by multi-platform technology Long history with titles on almost every console that ever existed Most studios have annual cycles that cannot be broken Both developer and publisher with ownership in many huge studios Origin Of Tiburon Founded by 3 programmers in Longwood, FL First title was MechWarrior for SNES First Madden title was Madden 96 for Genesis, SNES Acquired by EA in 1998 How Tiburon Got Madden Originally, EA contracted Visual -

The Art of Play: Video Games Exhibit Opens at Museum in Washington

29 March 2012 | MP3 at voaspecialenglish.com The Art of Play: Video Games Exhibit Opens at Museum in Washington VOA The new exhibit at the Smithsonian's National Museum of American Art JUNE SIMMS: Welcome to AMERICAN MOSAIC in VOA Special English. (MUSIC) I'm June Simms. On the program today, we play new music from Justin Townes Earle … And we return to a story about the sale of shares in a company that operates a famous New York skyscraper … But first, we go play games at an art show in Washington. (MUSIC) "The Art of Video Games" JUNE SIMMS: Most art exhibits have a no-touch policy. At the Smithsonian Institution, guards often give a warning if people position themselves too close to works of art. But, right now, the Smithsonian's National Museum of American Art 2 is inviting visitors to play with parts of its new exhibit, "The Art of Video Games." Mario Ritter has our story. MARIO RITTER: Six-year-old gamer Jacob Smith enjoys playing at the museum. JACOB SMITH: "Awesome." Jacob was prepared to take a favorite video game he found there. JACOB SMITH: "I was really excited. I think that you could buy games here. Like I have some money." But none of the eighty games are for sale. They all are on loan from Chris Melissinos, who set up the show. CHRIS MELISSINOS: "Video games have been present in my life since as long as I can remember." Chris Melissinos sees video games as more than just play things. He suspects other people feel the same way. -

In 193X, Constance Rourke's Book American Humor Was Reviewed In

OUR LIVELY ARTS: AMERICAN CULTURE AS THEATRICAL CULTURE, 1922-1931 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Jennifer Schlueter, M.A. ***** The Ohio State University 2007 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Thomas Postlewait, Adviser Professor Lesley Ferris Adviser Associate Professor Alan Woods Graduate Program in Theatre Copyright by Jennifer Schlueter c. 2007 ABSTRACT In the first decades of the twentieth century, critics like H.L. Mencken and Van Wyck Brooks vociferously expounded a deep and profound disenchantment with American art and culture. At a time when American popular entertainments were expanding exponentially, and at a time when European high modernism was in full flower, American culture appeared to these critics to be at best a quagmire of philistinism and at worst an oxymoron. Today there is still general agreement that American arts “came of age” or “arrived” in the 1920s, thanks in part to this flogging criticism, but also because of the powerful influence of European modernism. Yet, this assessment was not, at the time, unanimous, and its conclusions should not, I argue, be taken as foregone. In this dissertation, I present crucial case studies of Constance Rourke (1885-1941) and Gilbert Seldes (1893-1970), two astute but understudied cultural critics who saw the same popular culture denigrated by Brooks or Mencken as vibrant evidence of exactly the modern American culture they were seeking. In their writings of the 1920s and 1930s, Rourke and Seldes argued that our “lively arts” (Seldes’ formulation) of performance—vaudeville, minstrelsy, burlesque, jazz, radio, and film—contained both the roots of our own unique culture as well as the seeds of a burgeoning modernism.