Why Services Won't Always Buy Legitimacy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HEALTH CLUSTER PAKISTAN Crisis in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Issue No 4

HEALTH CLUSTER PAKISTAN Crisis in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Issue No 4 20 March‐12 April, 2010 • As of 15 April, 300,468 individuals or 42 924 families are living with host communities in Hangu (15187 families,106 309 individuals) Peshawar(1910 families,13370 individuals) and Kohat(25827 families,180789 individuals) Districts, displaced from Orakzai and Kurram Agency, of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province formally known as North West Frontier Province (NWFP). • In addition to above there are 2 33 688 families or 1 404 241 people are living outside camps with host communities in Mardan, Swabi, Charssada, Pakistan IDPs living in camps and Host Nowshera,Kohat, Hangu Tank, communities DIKhan, Peshawar Abbotabad, Haripur, Mansehra and Battagram districts of NWFP. There are 23 784 families or 121 760 individuals living in camps of Charssada, Nowsehra, Lower Dir, Hangu and Malakand districts (Source: Commissionerate for Afghan Refugees and National Data Base Authority) • In order to cater for the health sector needs, identified through recent health assessment conducted by health cluster partners, in Kohat and Hangu districts due to ongoing military operation in Orakzai Agency, Health cluster partners ( 2 UN and 8 I/NGO’s have received 2.4 million dollars fund from Central Emergency Response Fund (CERF). This fund will shoulder the ongoing health response for the IDPs and host communities living in Kohat and Hangu Districts 499 DEWS health facilities reported 133 426 consultations from 20-26 March, of which 76 909 (58 %) were reported for female consultations and 56 517 (42%) for male. Children aged under 5 years represented 33 972 (25%) of all consultations. -

S# BRANCH CODE BRANCH NAME CITY ADDRESS 1 24 Abbottabad

BRANCH S# BRANCH NAME CITY ADDRESS CODE 1 24 Abbottabad Abbottabad Mansera Road Abbottabad 2 312 Sarwar Mall Abbottabad Sarwar Mall, Mansehra Road Abbottabad 3 345 Jinnahabad Abbottabad PMA Link Road, Jinnahabad Abbottabad 4 131 Kamra Attock Cantonment Board Mini Plaza G. T. Road Kamra. 5 197 Attock City Branch Attock Ahmad Plaza Opposite Railway Park Pleader Lane Attock City 6 25 Bahawalpur Bahawalpur 1 - Noor Mahal Road Bahawalpur 7 261 Bahawalpur Cantt Bahawalpur Al-Mohafiz Shopping Complex, Pelican Road, Opposite CMH, Bahawalpur Cantt 8 251 Bhakkar Bhakkar Al-Qaim Plaza, Chisti Chowk, Jhang Road, Bhakkar 9 161 D.G Khan Dera Ghazi Khan Jampur Road Dera Ghazi Khan 10 69 D.I.Khan Dera Ismail Khan Kaif Gulbahar Building A. Q. Khan. Chowk Circular Road D. I. Khan 11 9 Faisalabad Main Faisalabad Mezan Executive Tower 4 Liaqat Road Faisalabad 12 50 Peoples Colony Faisalabad Peoples Colony Faisalabad 13 142 Satyana Road Faisalabad 585-I Block B People's Colony #1 Satayana Road Faisalabad 14 244 Susan Road Faisalabad Plot # 291, East Susan Road, Faisalabad 15 241 Ghari Habibullah Ghari Habibullah Kashmir Road, Ghari Habibullah, Tehsil Balakot, District Mansehra 16 12 G.T. Road Gujranwala Opposite General Bus Stand G.T. Road Gujranwala 17 172 Gujranwala Cantt Gujranwala Kent Plaza Quide-e-Azam Avenue Gujranwala Cantt. 18 123 Kharian Gujrat Raza Building Main G.T. Road Kharian 19 125 Haripur Haripur G. T. Road Shahrah-e-Hazara Haripur 20 344 Hassan abdal Hassan Abdal Near Lari Adda, Hassanabdal, District Attock 21 216 Hattar Hattar -

(I) Kabal BAR ABA KHEL 2 78320

Appointment of Teachers (Adhoc School Based) in Elementary & Secondary Education department, Khyber Pakhutunkhwa (Recruitment Test)) Page No.1 Test held on 20th, 26th & 27th November 2016 Final Merit List (PST-Male) Swat NTS Acad:Ma Marks SSC HSSC Bachelor BS Hons. Master M.Phill Diploma M.Ed/MA.Ed rks [out of 100] [Out of 100] Total (H=A+B+ Candidate RollN Date Of 20% 35% 15% 5% 15% Marks [Out Father Name Total 20% (A) Obt Total 20% (B) Obt Total Obt Total Obt Total Obt Total Obt Total Obt Total 5% (G) C+D+E+ Mobile Union Address REMARKS Tehsil Sr Name School Name Obt (I) of 200] o Birth (C) (C) (D) (E) (F) F+G) Name U.C Name apply for J=H+I Council GPS 78320 0347975 BAR ABA VILLAGE AND POST OFFICE SIR SINAI BAR ABA 2 CHINDAKHW AHMAD ALI 1993-5-8 792.0 1050.015.09 795.0 1100.014.45 0.0 0.0 0.0 3409.04300.027.75 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 644.0 900.0 10.73 0.0 0.0 0.0 68.02 63.0 131.02 TAHIR ALI 9647 KHEL TEHSIL KABAL SWAT Kabal KHEL 01098 ARA 78320 0347975 BAR ABA VILLAGE AND POST OFFICE SIR SINAI BAR ABA 3 GPS DERO AHMAD ALI 1993-5-8 792.0 1050.015.09 795.0 1100.014.45 0.0 0.0 0.0 3409.04300.027.75 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 644.0 900.0 10.73 0.0 0.0 0.0 68.02 63.0 131.02 TAHIR ALI 9647 KHEL TEHSIL KABAL SWAT Kabal KHEL 01098 CHUM 78320 0347975 BAR ABA VILLAGE AND POST OFFICE SIR SINAI BAR ABA 3 AHMAD ALI 1993-5-8 792.0 1050.015.09 795.0 1100.014.45 0.0 0.0 0.0 3409.04300.027.75 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 644.0 900.0 10.73 0.0 0.0 0.0 68.02 63.0 131.02 TAHIR ALI 9647 KHEL TEHSIL KABAL SWAT Kabal KHEL 01098 GPS KABAL 78320 0347975 BAR ABA VILLAGE -

Text in Community Study Guide

Text in Community Study Guide I am Malala—Malala Yousafzai w/ Christine Lamb Created by—Dr. Michael K. Cundall, Jr., Darrell Hairston, and Anna Whiteside: University Honors Program Prologue: The Day My World Changed/ Chapter 1: A Daughter is Born 1) Why do so few people in Pakistan celebrate the birth of a baby girl? What is the attitude of Malala’s father’s toward the birth his daughter? 2) After whom is Malala named? 3) What are society’s expectations of girls? What are the attitudes of Malala and her father about the role of girls in society? 4) Before she was shot, did Malala fear for her own life? 5) Why do you think the KPK is independent? Does this cultural and geographical independence from the main part of Pakistan mean anything for the rest of Malala’s story? 6) What did Alexander the Great do when he reached the Swat Valley? 7) What are the various religions that have “ruled” the Swat Valley? The Swat Valley, Malala’ Yousafzai’s hometown, is known for its mountains, meadows, and lakes. Tourists often call it “the Switzerland of the East.” The Swat Valley was the home of Pakistan’s first ski resort. (Map Showing the Location of Swat District, Source: Pahari Sahib, Wikimedia Commons) The SWAT valley’s population is mostly made up of ethnic Gujjar and Pashtuns. The Yousafzais are Pashtuns, a group whose population is located primarily in Afghanistan and northwestern and western parts of Iran. (Ghabral, Swat Valley. Source: Isrum, Wikimedia Commons) (Mahu Dan Swat Valley, Source: Isruma, Wikimedia Commons) (Snow covered mountain in Sway Valley, Source: Isruma, Wikimedia Commons) The Swat valley is home to several relics left over from the Buddhist Reign in the third century BC. -

Usg Humanitarian Assistance to Pakistan in Areas

USG HUMANITARIAN ASSISTANCE TO CONFLICT-AFFECTED POPULATIONS IN PAKISTAN IN FY 2009 AND TO DATE IN FY 2010 Faizabad KEY TAJIKISTAN USAID/OFDA USAID/Pakistan USDA USAID/FFP State/PRM DoD Amu darya AAgriculture and Food Security S Livelihood Recovery PAKISTAN Assistance to Conflict-Affected y Local Food Purchase Populations ELogistics Economic Recovery ChitralChitral Kunar Nutrition Cand Market Systems F Protection r Education G ve Gilgit V ri l Risk Reduction a r Emergency Relief Supplies it a h Shelter and Settlements C e Food For Progress I Title II Food Assistance Shunji gol DHealth Gilgit Humanitarian Coordination JWater, Sanitation, and Hygiene B and Information Management 12/04/09 Indus FAFA N A NWFPNWFP Chilas NWFP AND FATA SEE INSET UpperUpper DirDir SwatSwat U.N. Agencies, E KohistanKohistan Mahmud-e B y Da Raqi NGOs AGCJI F Asadabad Charikar WFP Saidu KUNARKUNAR LowerLower ShanglaShangla BatagramBatagram GoP, NGOs, BajaurBajaur AgencyAgency DirDir Mingora l y VIJaKunar tro Con ImplementingMehtarlam Partners of ne CS A MalakandMalakand PaPa Li Î! MohmandMohmand Kabul Daggar MansehraMansehra UNHCR, ICRC Jalalabad AgencyAgency BunerBuner Ghalanai MardanMardan INDIA GoP e Cha Muzaffarabad Tithwal rsa Mardan dd GoP a a PeshawarPeshawar SwabiSwabi AbbottabadAbbottabad y enc Peshawar Ag Jamrud NowsheraNowshera HaripurHaripur AJKAJK Parachinar ber Khy Attock Punch Sadda OrakzaiOrakzai TribalTribal AreaArea Î! Adj.Adj. PeshawarPeshawar KurrumKurrum AgencyAgency Islamabad Gardez TribalTribal AreaArea AgencyAgency Kohat Adj.Adj. KohatKohat Rawalpindi HanguHangu Kotli AFGHANISTAN KohatKohat ISLAMABADISLAMABAD Thal Mangla reservoir TribalTribal AreaArea AdjacentAdjacent KarakKarak FATAFATA BannuBannu us Bannu Ind " WFP Humanitarian Hub NorthNorth WWaziristanaziristan BannuBannu SOURCE: WFP, 11/30/09 Bhimbar AgencyAgency SwatSwat" TribalTribal AreaArea " Adj.Adj. -

Socio-Economic Conditions of Post-Conflict Swat: a Critical Appraisal

TIGAH,,, A JOURNAL OF PEACE AND DEVELOPMENT Volume: II, December 2012, TigahFATA Research Centre, Islamabad Socio-Economic Conditions of Post-Conflict Swat: A Critical Appraisal * Dr. Salman Bangash Background of Conflict in Swat The Pakistani province of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KPK), previously known as the North West Frontier Province (NWFP) lies between the Indus River in the east and the Suleiman mountain range in the west, with an area of 74,521 sq. km. It comprises of 18 districts and Provincially Administered Tribal Area (PATA), consisting of Malakand Agency, which is further divided into districts of Upper Dir, Lower Dir, Chitral, Swat, Buner, Shangla and areas of Kala Dhaka. Swat is one of the districts of PATA, Malakand Division. Swat is a mountainous region with varying elevations, ranging from 600 meters to 6000 meters above the sea level, from south to north to the foothills of Hindukush mountain range. The region is blessed with abundance of water in shape of the Swat River. It also has forests, lush green valleys, plains and glaciers. The Swat valley is rich in flora and fauna. It is famous for its variety of fruits, medicinal herbs and botanical plants. The total area of District Swat is 5337 sq. km, divided into two tehsils, namely Matta (683 sq. km) and Swat (4654 sq. km).The total forest cover in Swat is 497,969 acres which consists of varieties of Pine trees. The District Headquarter of Swat is Saidu Sharif, but the main town in the district is Mingora. Saidu Sharif is at a distance of 131 km from Peshawar, the provincial capital, towards the northeast, * The author is a Lecturer at the Department of History, University of Peshawar. -

Phenoloy and Yield of Sweet Corn Landraces Influenced by Planting Dates

Sarhad J. Agric. Vol.25, No.2, 2009 PHENOLOY AND YIELD OF SWEET CORN LANDRACES INFLUENCED BY PLANTING DATES ZAFAR HAYAT KHAN*, SHAD KHAN KHALIL*, SHAHEEN NIGAR**, IFTIKHAR H. KHALIL***, IKRAMUL HAQ*****, IFTIKHAR AHMAD*****, ASAD ALI**** and M. YASIR KHAN*** * Department of Agronomy, NWFP Agricultural University, Peshawar, Pakistan ** Institute of Development Studies, NWFP Agricultural University, Peshawar, Pakistan *** Department of Plant Breeding & Genetics, NWFP Agricultural University, Peshawar, Pakistan **** Department of Plant Pathology, NWFP Agricultural University, Peshawar, Pakistan ***** Department of Agricultural Extension Education & Communication, NWFP Agricultural University, Peshawar, Pakistan ABSTRACT This study was conducted to determine the production potential and optimum sowing date for various landraces of sweet corn. The research was carried out at New Developmental Farm, NWFP Agricultural University Peshawar, Pakistan during 2007 crop season. Sowing dates were 25 April (D1), 25 May (D2), 16 June (D3), 26 July (D4) and 18 August (D5). Sweet corn landraces Mingora, Mansehra, Swabi, Parachinar and cv. Azam were used. All parameters were significantly affected by sowing dates, landraces and their interaction. Days to 50 % tasseling and 50 % silking decreased as the date of sowing was delayed from D1 to D5. Days to maturity decreased as the date of sowing was delayed from D1 to D3 and then increased again as sowing was delayed from D3 to D5. Sweet corn landrace Swabi produced maximum (17292 kg ha-1) biological yield from D1 sowing compared to minimum (7083 kg ha-1) produced by Parachinar on D5. Azam produced maximum grain yield (4097 kg ha-1) and harvest index (27.21 %) when sown on D4, where as minimum grain yield (621 kg ha-1) and harvest index (7.16 %) was observed for Parachinar and Mingora respectively on D5 sowing. -

Reclaiming Prosperity in Khyber- Pakhtunkhwa

Working paper Reclaiming Prosperity in Khyber- Pakhtunkhwa A Medium Term Strategy for Inclusive Growth Full Report April 2015 When citing this paper, please use the title and the following reference number: F-37109-PAK-1 Reclaiming Prosperity in Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa A Medium Term Strategy for Inclusive Growth International Growth Centre, Pakistan Program The International Growth Centre (IGC) aims to promote sustainable growth in developing countries by providing demand-led policy advice informed by frontier research. Based at the London School of Economics and in partnership with Oxford University, the IGC is initiated and funded by DFID. The IGC has 15 country programs. This report has been prepared under the overall supervision of the management team of the IGC Pakistan program: Ijaz Nabi (Country Director), Naved Hamid (Resident Director) and Ali Cheema (Lead Academic). The coordinators for the report were Yasir Khan (IGC Country Economist) and Bilal Siddiqi (Stanford). Shaheen Malik estimated the provincial accounts, Sarah Khan (Columbia) edited the report and Khalid Ikram peer reviewed it. The authors include Anjum Nasim (IDEAS, Revenue Mobilization), Osama Siddique (LUMS, Rule of Law), Turab Hussain and Usman Khan (LUMS, Transport, Industry, Construction and Regional Trade), Sarah Saeed (PSDF, Skills Development), Munir Ahmed (Energy and Mining), Arif Nadeem (PAC, Agriculture and Livestock), Ahsan Rana (LUMS, Agriculture and Livestock), Yasir Khan and Hina Shaikh (IGC, Education and Health), Rashid Amjad (Lahore School of Economics, Remittances), GM Arif (PIDE, Remittances), Najm-ul-Sahr Ata-ullah and Ibrahim Murtaza (R. Ali Development Consultants, Urbanization). For further information please contact [email protected] , [email protected] , [email protected] . -

Forestry in the Princely State of Swat and Kalam (North-West Pakistan)

Forestry in the Princely State of Swat and Kalam (North-West Pakistan) A Historical Perspective on Norms and Practices IP6 Working Paper No.6 Sultan-i-Rome, Ph.D. 2005 Forestry in the Princely State of Swat and Kalam (North-West Pakistan) A Historical Perspective on Norms and Practices IP6 Working Paper No.6 Sultan-i-Rome, Ph.D. 2005 The Swiss National Centre of Competence in Research (NCCR) North-South is based on a network of partnerships with research institutions in the South and East, focusing on the analysis and mitigation of syndromes of global change and globalisation. Its sub-group named IP6 focuses on institutional change and livelihood strategies: State policies as well as other regional and international institutions – which are exposed to and embedded in national economies and processes of globalisation and global change – have an impact on local people's livelihood practices and strategies as well as on institutions developed by the people themselves. On the other hand, these institutionally shaped livelihood activities have an impact on livelihood outcomes and the sustainability of resource use. Understanding how the micro- and macro-levels of this institutional context interact is of vital importance for developing sustainable local natural resource management as well as supporting local livelihoods. For an update of IP6 activities see http://www.nccr-north-south.unibe.ch (>Individual Projects > IP6) The IP6 Working Paper Series presents preliminary research emerging from IP6 for discussion and critical comment. Author Sultan-i-Rome, Ph.D. Village & Post Office Hazara, Tahsil Kabal, Swat–19201, Pakistan e-mail: [email protected] Distribution A Downloadable pdf version is availale at www.nccr- north-south.unibe.ch (-> publications) Cover Photo The Swat Valley with Mingawara, and Upper Swat in the background (photo Urs Geiser) All rights reserved with the author. -

Swat District !

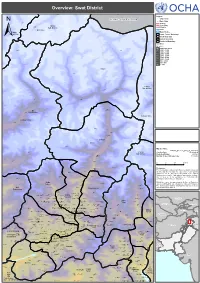

! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Overview: Swat District ! ! ! ! SerkiSerki Chikard Legend ! J A M M U A N D K A S H M I R Citiy / Town ! Main Cities Lohigal Ghari ! Tertiary Secondary Goki Goki Mastuj Shahi!Shahi Sub-division Primary CHITRAL River Chitral Water Bodies Sub-division Union Council Boundary ± Tehsil Boundary District Boundary ! Provincial Boundary Elevation ! In meters ! ! 5,000 and above Paspat !Paspat Kalam 4,000 - 5,000 3,000 - 4,000 ! ! 2,500 - 3,000 ! 2,000 - 2,500 1,500 - 2,000 1,000 - 1,500 800 - 1,000 600 - 800 0 - 600 Kalam ! ! Utror ! ! Dassu Kalam Ushu Sub-division ! Usho ! Kalam Tal ! Utrot!Utrot ! Lamutai Lamutai ! Peshmal!Harianai Dir HarianaiPashmal Kalkot ! ! Sub-division ! KOHISTAN ! ! UPPER DIR ! Biar!Biar ! Balakot Mankial ! Chodgram !Chodgram ! ! Bahrain Mankyal ! ! ! SWAT ! Bahrain ! ! Map Doc Name: PAK078_Overview_Swat_a0_14012010 Jabai ! Pattan Creation Date: 14 Jan 2010 ! ! Sub-division Projection/Datum: Baranial WGS84 !Bahrain BahrainBarania Nominal Scale at A0 paper size: 1:135,000 Ushiri ! Ushiri Madyan ! 0 5 10 15 kms ! ! ! Beshigram Churrai Churarai! Disclaimers: Charri The designations employed and the presentation of material Tirat Sakhra on this map do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Beha ! Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, Bar Thana Darmai Fatehpur city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the Kwana !Kwana delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Kalakot Matta ! Dotted line represents a!pproximately the Line of Control in Miandam Jammu and Kashmir agreed upon by India and Pakistan. Sebujni Patai Olandar Paiti! Olandai! The final status of Jammu and Kashmir has not yet been Gowalairaj Asharay ! Wari Bilkanai agreed upon by the parties. -

Religious and Cultural Tourism to the Ancient Gandhara Region Promotes Multiculturalism, Interfaith Harmony and Peace

ALFP e-magazine issue 6: Migration and Multicultural Coexistence Religious and Cultural Tourism to the Ancient Gandhara Region Promotes Multiculturalism, Interfaith Harmony and Peace Fazal Khaliq (Pakistan) Reporter, Dawn Media Group / Cultural Activist / ALFP 2017 Fellow The Gandhara region in the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province of Pakistan was the center of multicultural and multi-religious activities, and people of diverse cultures lived there in harmony about 2000 years ago. Followers of different religions and cultures like Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism, Zoroastrianism, Persian, Greek and Roman faiths lived peacefully. A place where the concept of religious harmony emerged and developed, Gandhara became the first perfect model of multicultural coexistence on the globe, according to archeologists and cultural experts. The region was also a busy center of educational, religious, cultural and trade activities between South Asia, Central Asia, Southeast Asia and Europe with a continuous stream of people migrating in and out of it. The infusion of ideas helped Gandharan art achieve a matchless identity with its diversity and sublime themes. In short, we can claim that Gandhara was the first region to have international influences of globalization with business and other activities. Today, parts of the Gandhara region in Pakistan, including Taxila, Peshawar, Charsadda, Mardan, Swat, Buner, Malakand and Dir, contain thousands of sacred archaeological remains of immense importance for Buddhists, Hindus, Persians, Greeks and Romans, as well as Muslims, and people from across the world want to visit the area to view the sites. View of a Buddhist stupa and complex at Amlook Dara, Swat (Photo by the author) © 2020 International House of Japan and Japan Foundation ALFP e-magazine issue 6: Migration and Multicultural Coexistence However, due to a lack of awareness and misguided religious beliefs, local Muslim communities consider the archeological remains as mere ruins or structures that provide them no benefits. -

Administrative System of the Princely State of Swat

Administrative System of the Princely State of Swat Dr. SULTAN -I- ROME www.valleyswat.net Administrative System of the Princely State of Swat Courtesy: Sultan-I-Rome Copyright 2006. J.R.S.P. Vol. XXXXIII. No. 2, 2006 Download more papers and articles at ValleySwat. www.valleyswat.net 1 Administrative System of the Princely State of Swat Situated in the North-West Frontier Province of British India and later Pakistan, Swat State has the distinction of not being imposed by an imperial power or an individual but was founded in 1915 by jarga of a section of the right bank Swat Valley after doing away with the rule of the Nawab of Dir over their areas. The youngest of the Princely States of India and dependent upon British Indian Government and later Pakistan for currency, post and telegraph, and foreign affairs and later on electricity as well, Swat State was internally independent. It had "its own laws, its own system of justice, army, police and administration, budget and taxes,"1 and also its own flag with an emblem-of-a fort in golden green background. Swat State was probably the only governmental machine in the contemporary world which was run without superfluity of paper work, opined by Martin Moore." Originator of the administrative system of the State was Abdul Jabbar Shah, the first ruler of the State 0915-1917), which was modified, developed and refined by his successors at the seat of the State, namely Miangul Abdul Wadud who ruled from 1917 till 1949 and Miangul Jahanzeb who ruled from 1949 till the merger of the State in 1969.