Damian Lemos

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Eingorn, Viacheslav

A Rock-Solid Chess Opening Repertoire for Black Viacheslav Eingorn First published in the UK by Gambit Publications Ltd 2012 Copyright © Viacheslav Eingom 2012 The right of Viacheslav Eingom to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordancewith the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No partof this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without prior permission of the publisher. In particular, no part of this publication may be scanned, transmitted via the Internet or uploaded to a website without the pub lisher's permission. Any personwho does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damage. ISBN-13: 978-1-906454-31-9 ISBN-10: 1-906454-31-0 DISTRIBUTION: Worldwide (except USA): Central Books Ltd, 99 Wallis Rd, London E9 5LN, England. Tel +44 (0)20 8986 4854 Fax +44 (0)20 8533 5821. E-mail: [email protected] Gambit Publications Ltd, 99 Wallis Rd, London E9 5LN, England. E-mail: [email protected] Website (regularly updated): www.gambitbooks.com Edited by Graham Burgess Typeset by Petra Nunn Cover image by WolffMorrow Printed in Great Britain by the MPG Books Group, Bodmin and King's Lynn 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Gambit Publications Ltd Managing Director: Murray Chandler GM Chess Director: Dr John Nunn GM Editorial Director: Graham Burgess FM GermanEditor: Petra Nunn -

TCAS II) by Personnel Involved in the Implementation and Operation of TCAS II

Preface This booklet provides the background for a better understanding of the Traffic Alert and Collision Avoidance System (TCAS II) by personnel involved in the implementation and operation of TCAS II. This booklet is an update of the TCAS II Version 7.0 manual published in 2000 by the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA). It describes changes to the CAS logic introduced by Version 7.1 and updates the information on requirements for use of TCAS II and operational experience. Version 7.1 logic changes will improve TCAS Resolution Advisory (RA) sense reversal logic in vertical chase situations. In addition all “Adjust Vertical Speed, Adjust” RAs are converted to “Level-Off, Level-Off” RAs to make it more clear that a reduction in vertical rate is required. The Minimum Operational Performance Standards (MOPS) for TCAS II Version 7.1 were approved in June 2008 and Version 7.1 units are expected to be operating by 2010-2011. Version 6.04a and 7.0 units are also expected to continue operating for the foreseeable future where authorized. 2 Preface................................................................................................................................. 2 The TCAS Solution............................................................................................................. 5 Early Collision Avoidance Systems................................................................................ 5 TCAS II Development .................................................................................................... 6 Initial -

Multilinear Algebra and Chess Endgames

Games of No Chance MSRI Publications Volume 29, 1996 Multilinear Algebra and Chess Endgames LEWIS STILLER Abstract. This article has three chief aims: (1) To show the wide utility of multilinear algebraic formalism for high-performance computing. (2) To describe an application of this formalism in the analysis of chess endgames, and results obtained thereby that would have been impossible to compute using earlier techniques, including a win requiring a record 243 moves. (3) To contribute to the study of the history of chess endgames, by focusing on the work of Friedrich Amelung (in particular his apparently lost analysis of certain six-piece endgames) and that of Theodor Molien, one of the founders of modern group representation theory and the first person to have systematically numerically analyzed a pawnless endgame. 1. Introduction Parallel and vector architectures can achieve high peak bandwidth, but it can be difficult for the programmer to design algorithms that exploit this bandwidth efficiently. Application performance can depend heavily on unique architecture features that complicate the design of portable code [Szymanski et al. 1994; Stone 1993]. The work reported here is part of a project to explore the extent to which the techniques of multilinear algebra can be used to simplify the design of high- performance parallel and vector algorithms [Johnson et al. 1991]. The approach is this: Define a set of fixed, structured matrices that encode architectural primitives • of the machine, in the sense that left-multiplication of a vector by this matrix is efficient on the target architecture. Formulate the application problem as a matrix multiplication. -

![Flight Dynamics Model Exchange Standard [AIAA10]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1588/flight-dynamics-model-exchange-standard-aiaa10-611588.webp)

Flight Dynamics Model Exchange Standard [AIAA10]

! BSR/AIAA S-119-201X Proposed ANSI National Standard !"#$%&'()*+,#-.'/012"'34-%+*$2'5&+*1+61' ' ' ' ' Draft 2010-04-23 ' ' ' ' Sponsored by 7,26#-+*'8*.&#&9&2'0:'7260*+9&#-.'+*1'7.&60*+9&#-.' Approved XX Month 201X '' Abstract ;%#.'#.'+'.&+*1+61':06'&%2'#*&26-%+*$2'0:'.#,9"+�*',012"#*$'1+&+'<2&=22*':+-#"#.>';%2'#*#&#+"'0<?2-&#@2' #.'&0'+""0='2+.)A'.&6+#$%&:06=+61'24-%+*$2.'0:'.#,9"+�*',012"'#*:06,+�*'+*1'1+&+'<2&=22*':+-#"#.>'' ;%2'.&+*1+61'+BB"#2.'&0'@#6&9+"")'+*)'@2%#-"2',012"'C$609*1A'+#6'06'.B+-2DA'<9&',0.&'1#62-&")'+BB"#2.'&0' +#6-6+:&'+*1',#..#"2.> ! " ! ' ' ' ' ' ' ' ' ' LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING DATA WILL BE ADDED HERE BY AIAA STAFF E9<"#.%21'<)' American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics 1801 Alexander Bell Drive, Reston, VA 20191 F0B)6#$%&'G'HIJK'7,26#-+*'8*.&#&9&2'0:'7260*+9&#-.'+*1' 7.&60*+9&#-.' 7""'6#$%&.'62.26@21' ' L0'B+6&'0:'&%#.'B9<"#-+�*',+)'<2'62B6019-21'#*'+*)':06,A'#*'+*'2"2-&60*#-'62&6#2@+"'.).&2,' 06'0&%26=#.2A'=#&%09&'B6#06'=6#&&2*'B26,#..#0*'0:'&%2'B9<"#.%26>' ' E6#*&21'#*'&%2'M*#&21'5&+&2.'0:'7,26#-+' ""! ! ! Contents F0*&2*&.>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>> ###' !062=061>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>> #@' 8*&6019-�* >>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>> -

CHESS MASTERPIECES: (Later, in Europe, Replaced by a HIGHLIGHTS from the DR

CHESS MASTERPIECES: (later, in Europe, replaced by a HIGHLIGHTS FROM THE DR. queen). These were typically flanKed GEORGE AND VIVIAN DEAN by elephants (later to become COLLECTION bishops), though in this case, they are EXHIBITION CHECKLIST camels with drummers; cavalrymen (later to become Knights); and World Chess Hall of Fame chariots or elephants, (later to Saint Louis, Missouri 2.1. Abstract Bead anD Dart Style Set become rooKs or “castles”). A September 9, 2011-February 12, with BoarD, India, 1700s. Natural and frontline of eight foot soldiers 2012 green-stained ivory, blacK lacquer- (pawns) completed each side. work folding board with silver and mother-of-pearl. This classical Indian style is influenced by the Islamic trend toward total abstraction of the design. The pieces are all lathe- turned. The blacK lacquer finish, made in India from the husKs of the 1.1. Neresheimer French vs. lac insect, was first developed by the Germans Set anD Castle BoarD, Chinese. The intricate inlaid silver Hanau, Germany, 1905-10. Silver and grid pattern traces alternating gilded silver, ivory, diamonds, squares filled with lacy inscribed fern sapphires, pearls, amethysts, rubies, leaf designs and inlaid mother-of- and marble. pearl disKs. These decorations 2.3. Mogul Style Set with combine a grid of squares, common Presentation Case, India, 1800s. Before WWI, Neresheimer, of Hanau, to Western forms of chess, with Beryl with inset diamonds, rubies, Germany, was a leading producer of another grid of inlaid center points, and gold, wooden presentation case ornate silverware and decorative found in Japanese and Chinese clad in maroon velvet and silk-lined. -

CHECKMATE PHARMACEUTICALS, INC. (Exact Name of Registrant As Specified in Its Charter)

UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 8-K CURRENT REPORT Pursuant to Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 Date of Report (Date of earliest event reported): May 13, 2021 CHECKMATE PHARMACEUTICALS, INC. (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) Delaware 001-39425 36-4813934 (State or other jurisdiction (Commission (I.R.S. Employer of incorporation) File Number) Identification No.) Checkmate Pharmaceuticals, Inc. 245 Main Street, 2nd Floor Cambridge, MA 02142 (Address of principal executive offices, including zip code) (617) 682-3625 (Registrant’s telephone number, including area code) Not Applicable (Former Name or Former Address, if Changed Since Last Report) Check the appropriate box below if the Form 8-K filing is intended to simultaneously satisfy the filing obligation of the registrant under any of the following provisions: ☐ Written communications pursuant to Rule 425 under the Securities Act (17 CFR 230.425) ☐ Soliciting material pursuant to Rule 14a-12 under the Exchange Act (17 CFR 240.14a-12) ☐ Pre-commencement communications pursuant to Rule 14d-2(b) under the Exchange Act (17 CFR 240.14d-2(b)) ☐ Pre-commencement communications pursuant to Rule 13e-4(c) under the Exchange Act (17 CFR 240.13e-4(c)) Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Trade Name of each exchange Title of each class Symbol(s) on which registered Common Stock, $0.0001 par value per share CMPI The Nasdaq Global Market Indicate by check mark whether the registrant is an emerging growth company as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act of 1933 (§ 230.405 of this chapter) or Rule 12b-2 of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 (§ 240.12b-2 of this chapter). -

Reshevsky Wins Playoff, Qualifies for Interzonal Title Match Benko First in Atlantic Open

RESHEVSKY WINS PLAYOFF, TITLE MATCH As this issue of CHESS LIFE goes to QUALIFIES FOR INTERZONAL press, world champion Mikhail Botvinnik and challenger Tigran Petrosian are pre Grandmaster Samuel Reshevsky won the three-way playoff against Larry paring for the start of their match for Evans and William Addison to finish in third place in the United States the chess championship of the world. The contest is scheduled to begin in Moscow Championship and to become the third American to qualify for the next on March 21. Interzonal tournament. Reshevsky beat each of his opponents once, all other Botvinnik, now 51, is seventeen years games in the series being drawn. IIis score was thus 3-1, Evans and Addison older than his latest challenger. He won the title for the first time in 1948 and finishing with 1 %-2lh. has played championship matches against David Bronstein, Vassily Smyslov (three) The games wcre played at the I·lerman Steiner Chess Club in Los Angeles and Mikhail Tal (two). He lost the tiUe to Smyslov and Tal but in each case re and prizes were donated by the Piatigorsky Chess Foundation. gained it in a return match. Petrosian became the official chal By winning the playoff, Heshevsky joins Bobby Fischer and Arthur Bisguier lenger by winning the Candidates' Tour as the third U.S. player to qualify for the next step in the World Championship nament in 1962, ahead of Paul Keres, Ewfim Geller, Bobby Fischer and other cycle ; the InterzonaL The exact date and place for this event havc not yet leading contenders. -

Chess Openings, 13Th Edition, by Nick Defirmian and Walter Korn

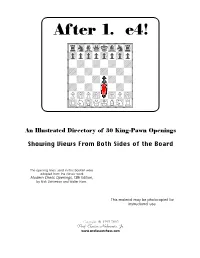

After 1. e4! cuuuuuuuuC {rhb1kgn4} {0p0p0p0p} {wdwdwdwd} {dwdwdwdw} {wdwdPdwd} {dwdwdwdw} {P)P)w)P)} {$NGQIBHR} vllllllllV An Illustrated Directory of 30 King-Pawn Openings Showing Views From Both Sides of the Board The opening lines used in this booklet were adopted from the classic work Modern Chess Openings, 13th Edition, by Nick DeFirmian and Walter Korn. This material may be photocopied for instructional use. Copyright © 1998-2002 Prof. Chester Nuhmentz, Jr. www.professorchess.com CCoonntteennttss This booklet shows the first 20 moves of 30 king-pawn openings. Diagrams are shown for every move. These diagrams are from White’s perspective after moves by White and from Black’s perspective after moves by Black. The openings are grouped into 6 sets. These sets are listed beginning at the bottom of this page. Right after these lists are some ideas for ways you might use these openings in your training. A note to chess coaches: Although the openings in this book give approximately even chances to White and Black, it won’t always look that way to inexperienced players. This can present problems for players who are continuing a game after using the opening moves listed in this booklet. Some players will need assistance to see how certain temporarily disadvantaged positions can be equalized. A good example of where some hints from the coach might come in handy is the sample King’s Gambit Declined (Set F, Game 2). At the end of the listed moves, White is down by a queen and has no immediate opportunity for a recapture. If White doesn’t analyze the board closely and misses the essential move Bb5+, he will have a lost position. -

Chess Pieces – Left to Right: King, Rook, Queen, Pawn, Knight and Bishop

CCHHEESSSS by Wikibooks contributors From Wikibooks, the open-content textbooks collection Permission is granted to copy, distribute and/or modify this document under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.2 or any later version published by the Free Software Foundation; with no Invariant Sections, no Front-Cover Texts, and no Back-Cover Texts. A copy of the license is included in the section entitled "GNU Free Documentation License". Image licenses are listed in the section entitled "Image Credits." Principal authors: WarrenWilkinson (C) · Dysprosia (C) · Darvian (C) · Tm chk (C) · Bill Alexander (C) Cover: Chess pieces – left to right: king, rook, queen, pawn, knight and bishop. Photo taken by Alan Light. The current version of this Wikibook may be found at: http://en.wikibooks.org/wiki/Chess Contents Chapter 01: Playing the Game..............................................................................................................4 Chapter 02: Notating the Game..........................................................................................................14 Chapter 03: Tactics.............................................................................................................................19 Chapter 04: Strategy........................................................................................................................... 26 Chapter 05: Basic Openings............................................................................................................... 36 Chapter 06: -

Winawer First Edition 2019 by Thinkers Publishing Copyright © 2019 David Miedema

The Modernized French Defense Volume 1: Winawer First edition 2019 by Thinkers Publishing Copyright © 2019 David Miedema All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a re- trieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission from the publisher. All sales or enquiries should be directed to Thinkers Publishing, 9850 Landegem, Belgium. Email: [email protected] Website: www.thinkerspublishing.com Managing Editor: Romain Edouard Assistant Editor: Daniël Vanheirzeele Proofreading: Bernard Carpinter Software: Hub van de Laar Cover Design: Iwan Kerkhof Graphic Artist: Philippe Tonnard Back cover photo: Evert van de Worp and Aventus Production: BESTinGraphics ISBN: 9789492510495 D/2019/13730/2 The Modernized French Defense Volume 1: Winawer David Miedema Thinkers Publishing 2019 Key to Symbols ! a good move ⩲ White stands slightly better ? a weak move ⩱ Black stands slightly better !! an excellent move ± White has a serious advantage ?? a blunder ∓ Black has a serious advantage !? an interesting move +- White has a decisive advantage ?! a dubious move -+ Black has a decisive advantage □ only move → with an attack N novelty ↑ with an initiative ⟳ lead in development ⇆ with counterplay ⨀ zugzwang ∆ with the idea of = equality ⌓ better is ∞ unclear position ≤ worse is © with compensation for the + check sacrificed material # mate Bibliography John Watson, Play the French Viktor Moskalenko, The Wonderful -

Simple Cross-Check Models for the Krone Exchange Rate

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Bernhardsen, Tom Research Report Simple Cross-Check Models for the Krone Exchange Rate Staff Memo, No. 2008/1 Provided in Cooperation with: Norges Bank, Oslo Suggested Citation: Bernhardsen, Tom (2008) : Simple Cross-Check Models for the Krone Exchange Rate, Staff Memo, No. 2008/1, ISBN 978-82-7553-429-1, Norges Bank, Oslo, http://hdl.handle.net/11250/2507967 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/210183 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/deed.no www.econstor.eu NO 2008/1 Oslo, 13 March 2008 Staff Memo Monetary Policy Simple cross-check models for the krone exchange rate by Tom Bernhardsen Publications from Norges Bank can be ordered by e-mail: [email protected] or from:Norges Bank, Subscription service, P.O.Box. -

Double Fianchetto – the Modern Chess Lifestyle

DOUBLE-FIANCHETTO THE MODERN CHESS LIFESTYLE by Daniel Hausrath www.thinkerspublishing.com Managing Editor Romain Edouard Assistant Editor Daniel Vanheirzeele Graphic Artist Philippe Tonnard Cover design Iwan Kerkhof Typesetting i-Press ‹www.i-press.pl› First edition 2020 by Th inkers Publishing Double-Fianchetto — the Modern Chess Lifestyle Copyright © 2020 Daniel Hausrath All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission from the publisher. ISBN 978-94-9251-075-4 D/2020/13730/3 All sales or enquiries should be directed to Th inkers Publishing, 9850 Landegem, Belgium. e-mail: [email protected] website: www.thinkerspublishing.com TABLE OF CONTENTS KEY TO SYMBOLS 5 PREFACE 7 PART 1. DOUBLE FIANCHETTO WITH WHITE 9 Chapter 1. Double fi anchetto against the King’s Indian and Grünfeld 11 Chapter 2. Double fi anchetto structures against the Dutch 59 Chapter 3. Double fi anchetto against the Queen’s Gambit and Tarrasch 77 Chapter 4. Diff erent move orders to reach the Double Fianchetto 97 Chapter 5. Diff erent resulting positions from the Double Fianchetto and theoretically-important nuances 115 PART 2. DOUBLE FIANCHETTO WITH BLACK 143 Chapter 1. Double fi anchetto in the Accelerated Dragon 145 Chapter 2. Double fi anchetto in the Caro Kann 153 Chapter 3. Double fi anchetto in the Modern 163 Chapter 4. Double fi anchetto in the “Hippo” 187 Chapter 5. Double fi anchetto against 1.d4 205 Chapter 6. Double fi anchetto in the Fischer System 231 Chapter 7.