CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, NORTHRIDGE The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Cause of Misfire in Counter-Terrorist Financing Regulation

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Making a Killing: The Cause of Misfire in Counter-Terrorist Financing Regulation A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science by Ian Oxnevad June 2019 Dissertation Committee: Dr. John Cioffi, Chairperson Dr. Marissa Brookes Dr. Fariba Zarinebaf Copyright by Ian Oxnevad 2019 The Dissertation of Ian Oxnevad is approved: ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Making a Killing: The Cause of Misfire in Counter-Terrorist Financing Regulation by Ian Oxnevad Doctor of Philosophy, Graduate Program in Political Science University of California, Riverside, June 2019 Dr. John Cioffi, Chairperson Financial regulations designed to counter the financing of terrorism have spread internationally over past several decades, but little is known about their effectiveness or why certain banks get penalized for financing terrorism while others do not. This research addresses this question and tests for the effects of institutional linkages between banks and states on the enforcement of these regulations. It is hypothesized here that a bank’s institutional link to its home state is necessary to block attempted enforcement. This research utilizes comparative studies of cases in which enforcement and penalization were attempted, and examines the role of institutional links between the bank and state in these outcomes. The case comparisons include five cases in all, with three comprising positive cases in which enforcement was blocked, and two in which penalty occurred. Combined, these cases control for rival variables such as rule of law, state capacity, iv authoritarianism, and membership of a country in a regulatory body while also testing for the impact of institutional linkage between a bank and its state in the country’s national political economy. -

Der Fall Khashoggi: Eine Völkerrechtliche Analyse

Diplomarbeit zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades eines Magisters der Rechtswissenschaften an der Leopold-Franzens-Universität Innsbruck Der Fall Khashoggi: eine völkerrechtliche Analyse Eingereicht bei: Univ.-Prof. Dr. Walter Obwexer Von: Richard Purin Innsbruck, im Juli 2019 Danksagung Ich bedanke mich bei Herrn Univ.-Prof. Dr. Walter Obwexer, der meine Diplomarbeit betreut und begutachtet hat. Ebenfalls gebührt mein Dank Frau Dr. Jelka Mayr-Singer für die Betreuung und die konstruktive Kritik bei der Erstellung dieser Arbeit. Mein besonderer Dank gilt meinen Eltern, die in schwierigen Zeiten immer an meiner Seite waren. Ohne euch wäre all dies nicht möglich gewesen. II Eidesstattliche Erklärung Ich erkläre hiermit an Eides statt durch meine eigenhändige Unterschrift, dass ich die vorliegende Arbeit selbständig verfasst und keine anderen als die angegebenen Quellen und Hilfsmittel verwendet habe. Alle Stellen, die wörtlich oder inhaltlich den angegebenen Quellen entnommen wurden, sind als solche kenntlich gemacht. Die vorliegende Arbeit wurde bisher in gleicher oder ähnlicher Form noch nicht als Magister-/Master-/Diplomarbeit/Dissertation eingereicht. Datum Unterschrift III Inhalt Inhalt Abkürzungsverzeichnis ................................................................................................. VII I. Einleitung und Fragestellung ................................................................................... 1 II. Sachverhalt .............................................................................................................. -

Updates March 13, 2014)

Volume 12 | Issue 10 | Number 5 | Article ID 4090 | Mar 03, 2014 The Asia-Pacific Journal | Japan Focus The State, the Deep State, and the Wall Street Overworld 国と 深層国家と超支者ウォール・ストリート (Updates March 13, 2014) Peter Dale Scott traditional Washington partisan politics: the tip of the iceberg that Updated March 13, 2014. German a public watching C-SPAN sees translation available. daily and which is theoretically controllable via elections. The subsurface part of the iceberg I shall call the Deep State, which In the last decade it has become more and operates according to its own more obvious that we have in America today compass heading regardless of what the journalists Dana Priest and William 3 who is formally in power. Arkin have called At the end of 2013 a New York Times Op-Ed two governments: the one its noted this trend, and even offered a definition citizens were familiar with, of the term that will work for the purposes of operated more or less in the open: this essay: the other a parallel top secret government whose parts had mushroomed in less than a decade DEEP STATE n. A hard-to- into a gigantic, sprawling universe perceive level of government or of its own, visible to only a super-control that exists regardless carefully vetted cadre – and its of elections and that may thwart entirety…visible only to God.1 popular movements or radical change. Some have said that Egypt is being manipulated by its deep And in 2013, particularly after the military state.4 return to power in Egypt, more and more authors referred to this second level -

Jill+Dodd+Extract.Pdf

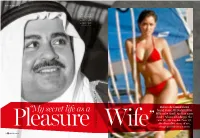

FIRST PERSON American model Jill Dodd (opposite) met high-rolling playboy Adnan Khashoggi (left) on a superyacht in Cannes in 1980 and moved into his harem in Marbella, Spain. C THE CURRENCY OF LOVE: A COURAGEOUS A COURAGEOUS THE CURRENCY OF LOVE: FROM FROM Before she founded surf “My secret life as a brand Roxy, Jill Dodd fell for BY JILL DODD. COPYRIGHT © 2017 BY JILL DODD. REPRINTED BY REPRINTED BY JILL DODD. BY © 2017 COPYRIGHT JILL DODD. BY billionaire Saudi Arabian arms dealer Adnan Khashoggi. She was 20. He was 44. Now 57, ” she shares her story of sex, drugs and life in a harem Pleasure OF JILL DODD COURTESY GETTY IMAGES; BY PHOTOGRAPHED WITHIN FINDING THE LOVE JOURNEY TO IN A DIVISION OF SIMON & SCHUSTER, BOOKS, PERMISSION OF ENLIVEN BOOKS/ATRIA Wife 62 marieclaire.com.au FIRST PERSON t took me a long time provide for all of your financial needs. to admit that I was in a You can travel with me anywhere. modern-day harem. I already If you need me, call me. I will always had enough shame shoved call you back within 24 hours and send a upon me by anyone I told plane to pick you up. If you stay with me about [my boyfriend] Adnan. for 10 years and you want to have my My friends were troubled child, I will marry you in a legal cere- about the fact that he was 24 years old- mony and we’ll have children together.” Clockwise from left: the harem was er than me. -

On Coercion in International Law

\\jciprod01\productn\N\NYI\52-1\NYI101.txt unknown Seq: 1 26-DEC-19 14:27 ON COERCION IN INTERNATIONAL LAW MOHAMED S. HELAL* I. INTRODUCTION .................................. 2 R II. TALES OF COERCION ............................. 10 R A. The Russian Interference in the 2016 U.S. Presidential Election .......................... 10 R B. The 2017 North Korean Nuclear Crisis ......... 24 R C. The 2018 Murder of Washington Post Columnist Jamal Khashoggi ............................. 37 R III. THE PROHIBITION ON INTERVENTION AND THE CONCEPT OF COERCION .......................... 47 R A. The Prohibition on Intervention in the Internal or External Affairs of States ...................... 47 R 1. The Doctrinal and Political Origins of the Prohibition on Intervention ................ 49 R 2. The Sources, Scope, and Content of the Prohibition on Intervention ................ 54 R B. Unlawful Ends: Intervention in the Domaine Reserv´ e´ of States............................. 65 R C. Unlawful Means: Coercion as the Instrument of Intervention.................................. 69 R 1. The Concept of Coercion................... 70 R 2. Defining Unlawful Coercion ............... 74 R a. The Nature of Coercion: Occurrent Coercion and Dispositional Coercion ........................... 75 R b. Measuring Coercion: The Impact of Coercion vs. The Legality of Coercion ........................... 76 R * Assistant Professor of Law, Moritz College of Law & Affiliated Faculty, Mershon Center for International Security Studies – The Ohio State Univer- sity. I thank Steven Darnell and Andrea Hearon for excellent research assis- tance, Matt Cooper of the Moritz College of Law Library for invaluable help with sources used in this article, and the editors of the N.Y.U. Journal of International Law & Politics for their outstanding work. For valuable feed- back on previous drafts of this article, I acknowledge with much gratitude Christiane Ahlborn, Cinnamon Carlarne, Ashley Deeks, Larissa van den Herik, Sean Murphy, Tom Ruys, Lucca Ferro, Peter Tzeng, J. -

Wraps Off Arms Sales in Lideast

Kuwaiti officials the "commonality of spare parts and training" that would be Wraps Off achieved by all states choos- sales drive to get Arai] ihg the same plane. This states to agree to make the 'Was a selling plus for those i Arms Sales Tiger their standard fighter. officials who want to build a Sudan and Qatar are identi- pan-Arab military force to fied in the Northrop docu- confront Israel. ments as prime sales tar- Arab officials also . report, In lideast gets, and Saudi Arabia or- that they were interested'I 7 26/75/ because of strong hints from B. -Jim Hoagland dered 60 Tigers this year. • British Aircraft Corp. Washington that the United„ Washington Post Persian Service States would eventually all BEIRUT, July 19—The made sales presentation to the Saudis for the Jaguar, a low sales of the Tiger to k United States and Western fighter-bomber capable of Egypt. American diplomats European nations are aban- carrying nuclear weapons, in the region concede that doning restraints they have long after it became known the theory that the United shown in the ,past as they within the aircraft Industry States could gain Increased race to sell billions of dol- that Saudi Arabia was shop- influence in Egypt by sup- lars of highly destructive ping for the planes for im- plying arms directly is an el- weapons to nations in the mediate transfer to Egypt. ement of official thinking. volatile, fabulously rich The Egyptians eventually Reliable sources have also Middle East. chose to let the Saudis buy reported that 50 to 60 Egyp- Conolstr on sales prac- (France's Mirage deep pene- tian air force technicians tices and the types of weap- tration bomber for them. -

L'affaire Khashoggi. Quelles Implications

L’affaire Khashoggi. Quelles implications régionales et internationales pour la Turquie ? Bayram Balci, Jean-Paul Burdy To cite this version: Bayram Balci, Jean-Paul Burdy. L’affaire Khashoggi. Quelles implications régionales et interna- tionales pour la Turquie ?. Etudes, 2019, pp.7 - 18. hal-02178104 HAL Id: hal-02178104 https://hal-sciencespo.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02178104 Submitted on 9 Jul 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Affaire Khashoggi : quelles implications régionales et internationales pour la Turquie ? Bayram BALCI, IFEA, CERI/Sciences Po Paris Jean-Paul BURDY, Sciences Po Grenoble Pour se rendre au sommet du G20 en Argentine (30 novembre-1er décembre 2018), puis pour en revenir, le prince-héritier saoudien, ministre de la Défense et chef de la Cour royale Mohammed ben Salmane a multiplié les étapes de « réhabilitation internationale » après « l’affaire Khashoggi »: reçu à bras ouverts (et sans surprise) à Abou Dhabi, Manama (Bahreïn) et Nouakchott (Mauritanie), conspué par des manifestants tunisiens et yéménites à Tunis, ignoré par le président Bouteflika (officiellement « grippé ») à Alger… A Buenos-Aires même, loin de se trouver ostracisé, ou d'être traité en "paria" comme le prédisaient certains experts, le prince héritier a été au contraire très entouré. -

Republic of Yemen Targetted by British for Destabilization

Click here for Full Issue of EIR Volume 26, Number 6, February 5, 1999 Republic of Yemen targetted by British for destabilization by Hussein al-Nadeem In the third week of December, as U.S. and British forces conduct terrorist operations outside Her Majesty’s domains. were bombing Iraq, a London-based terrorist group was Britain has previously refused to extradite terrorists seeking planning to launch operations to destabilize the Republic of asylum in Britain, while the individuals were charged with Yemen. Members of the Ansar Al-Sharia, directed from committing murders and assassinations in Egypt and other London by Mustafa Kamel (a.k.a. Abu Hamza Al-Masri, a Middle Eastern countries. British citizen and former CIA-Afghansi “mujahid,” who Abu Hamza’s case is even more complicated, because trains groups of young people for terrorist activities at his he is not only an asylum seeker, but has British citizenship. Finsbury Mosque in north London under the guardian eye The Yemeni request came in the context of investigations of British domestic intelligence, MI5), were arrested on Dec. conducted by the Yemeni security authorities into the group 23, 1998 in Yemen, as they were planning armed terrorist whose members were arrested on Dec. 23, including five operations. These terrorists were in contact with the Islamic British citizens (one of them the son of Abu Hamza) and Army of Abeen-Aden (affiliated with the London-based one French citizen, who were in possession of weapons and Egyptian Islamic Jihad), which had kidnapped 16 British explosives and were said to be involved in carrying out and Australian tourists a few days earlier. -

Reagan Library Topic Guide - Asia

Reagan Library Topic Guide - Asia Reagan Library topic guides are created by the Library staff from textual material currently available for research use. Material cited in the topic guides come from these collections: White House Staff and Office Collections White House Office of Records Management (WHORM) Subject Files White House Office of Records Management (WHORM) Alphabetical Files. The folders and case files listed on these topic guides may still have withdrawn material due to Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) restrictions. Most frequently withdrawn material includes national security classified material, personal privacy issues, protection of the President, etc. ASIA SEE ALSO: Afghanistan Amerasian Children Chennault, Anna China Gandhi, Indira Hong Kong India Indonesia Japan Korea Korean Airlines (KAL 007) Machine Tools Mansfield, Amb. Mike Marcos, Ferdinand Mother Teresa Olympics, 1988 Pakistan Philippines Taiwan Thailand Trade Vietnam WHORM SUBJECT FILE BE003 casefiles 192480, 250609 BE003-10 casefile 343309 BE003-14 casefile 145862 BE005 casefile 401111 CA casefiles 225976, 334676 12/8/2020 Asia-2 CA001 casefile 617928 CA005 casefiles 226737, 228799 CO001-03 entire category (Asia) CO001-06 entire category (Far East) CO014 entire category (Bangladesh) CO019 entire category (Bhutan) CO025 entire category (Burma) Case files: Begin-299999 Case files: 300000-453340 Case files: 453341 (1) Case files: 453341 (2) Case files: 453342-599999 Case files: 600000-End CO034 entire category (China) CO034-01 entire category (China, Republic -

NATIONAL DEVELOPMENT COMPANY V. TRIAD HOLDING CORPORATION 930 F.2D 253 (1991)1

Federal Rules of Civil Procedure Rule 4 Rule 4. Summons (e) Serving an Individual Within a Judicial District of the United States. Unless federal law provides otherwise, an individual--other than a minor, an incompetent person, or a person whose waiver has been filed--may be served in a judicial district of the United States by: (1) following state law for serving a summons in an action brought in courts of general jurisdiction in the state where the district court is located or where service is made; or (2) doing any of the following: (A) delivering a copy of the summons and of the complaint to the individual personally; (B) leaving a copy of each at the individual’s dwelling or usual place of abode with someone of suitable age and discretion who resides there; or (C) delivering a copy of each to an agent authorized by appointment or by law to receive service of process. NATIONAL DEVELOPMENT COMPANY v. TRIAD HOLDING CORPORATION 930 F.2d 253 (1991)1 For more than a half-century, the Federal Rules of approximately $3.5 million of Triad Asia’s assets Civil Procedure have permitted service upon an that should have been distributed to NDC when the individual by leaving a summons and complaint “at joint venture was dissolved. the individual’s dwelling house or usual place of abode.” For a half-century before that, Equity Rule It is the service of the summons and complaint on 13 had the same provision. With approximately 1.16 Khashoggi on December 22, 1986 that forms the billion passengers annually engaging in international basis of this appeal. -

Adnan Khashoggi, High-Living Saudi Arms Trader, Dies at 81

Adnan Khashoggi, High-Living Saudi Arms Trader, Dies at 81 By Stephen Kinzer June 6, 2017 Adnan Khashoggi, the flamboyant Saudi arms trader who rose to spectacular wealth in the 1970s and 1980s while treating the world to displays of decadence breathtaking even by the standards of that era, died on Tuesday in London. He was 81. His family announced his death in a statement. He had been undergoing treatment for Parkinson’s disease. When Saudi Arabia and other Arab states decided to embark on a vast armament program after the 1973 Arab-Israeli war, backed by billions of dollars in oil money, Mr. Khashoggi became their principal link to the American arms industry. For years, he was the middleman in most of Saudi Arabia’s arms purchases. Mr. Khashoggi had several brushes with the law but was never convicted of a crime. He was involved in many of his era’s highest- profile scandals, including Iran-contra and the Marcos family’s effort to spirit money out of the Philippines. One biography of him was titled “The Richest Man in the World,” and he was often described that way. It was not strictly accurate, but during the early 1980s, his wealth, estimated to be in the low billions, placed him in a tiny elite. His appetites were gargantuan, beyond the limits of vulgarity. At the peak of his wealth, he presided over 12 estates, including some in Europe and the Middle East; a 180,000-acre ranch in Kenya; and a two-floor Manhattan residence at Olympic Towers, next to St. -

Iran-Contra Affair

Report No. 87-339 F IRAN-CONTRA AFFAIR : BIOGRAPHICAL PROFILES Cheryl J. Rathbun Foreign Affairs Analyst and Carolyn L. Hatcher Technic a1 Info mation Specialist With the research assistance of Peter Kappas Foreign Affairs and National Defense Division GOlLt;RNfvlENT ;X)CUMENTS COLLECTION NORTHERN KENTUCKY UNlVERSlTY LIBRARY March 27, 1987 The Congressional Research Senice works exclusively for the Congress, conducting research, analyzing legislation, and providing information at the request of committees. Mem- bers, and their staf'fi. The Service makes such research available. without parti- san bias. in many forms including studies. reports, compila- tions, digests, and background briefings. Upon request, CRS assists committees in analyzing legislative proposals and issues, and in assessing the possible effects of these proposals and their alternatives. The Service's senior specialists and subject analysts are also at.ailab1e for personal consultations in their respective fields of expertise. AB S TRAC T This report provides biographical information on individuals who have been associated in public reports with the controversy surrounding the secret U.S. arms sales to Iran and the channeling of profits to the rebels or Contras in Nicaragua. The information has been compiled from public sources. The report will be updated periodically and complements the CRS Report 86-190 F, Iran-Contra Affair: A Chronology. INTRODUCTION On November 3, 1986, a Lebanese weekly magazine, Al-Shiraa, reported that Robert C. McFarlane, former National Security Adviser to the President, had secretly visited Tehran to discuss with Iranian officials a cessation of Iranian support for terrorist groups in exchange for the supply of U.S.