Association of Central Hypersomnia and Fatigue in Patients with Multiple Sclerosis: a Polysomnographic Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Anorexia/Cachexia Heart Failure Symptom Management Guideline for Adults, Age 19 and Older in British Columbia

Anorexia/Cachexia Heart Failure Symptom Management Guideline For adults, age 19 and older in British Columbia What is anorexia? Anorexia is a syndrome characterized by some or all of the following symptoms: loss of appetite, nausea, early satiety, weakness, fatigue, food aversion, and significant physical and/or psychological symptoms. Causes of anorexia are multifactorial and include fatigue, dyspnea, medication side-effects, nausea, depression, anxiety and sodium restricted diets, which may all be found in patients with heart failure. What is cachexia? Cachexia is a syndrome characterized by severe body weight, fat and muscle loss and increased protein catabolism due to underlying disease. The prevalence of cachexia is 16–42% in the heart failure population and is associated with a 50%, 18 month mortality risk independent of variables such as ejection fraction, age and functional ability. How is cachexia diagnosed? Chronic condition with >5% weight loss in <12 months; or body mass index (BMI) <20kg/m2; and 3 out of 5 additional criteria: 1) Fatigue, 2) Decreased muscle strength, 3) Anorexia, 4) Low muscle mass, 5) Abnormal biochemistry *Blood testing to diagnose cachexia in advanced stages of disease is not advocated. Reminder: Malnutrition also affects prognosis in patients with heart failure and is often found in early transitions of the disease. However this symptom management guideline will focus on the assessment and treatment of anorexia and cachexia. Approach to Managing Anorexia/Cachexia Assessment History: When did weight loss begin? How much weight was lost? Obtain baseline (dry) weight. How is [the patients] appetite? What do they eat or drink on a typical day? How has weight loss affected mood? Ask about: nausea, early satiety, dyspnea, poor oral hygiene, dysphagia, malabsorption, bowel habits. -

Cancer Cachexia and Fatigue

CME Palliative care Cancer cachexia and mechanisms (Fig 1). The cachectic Other cachectic factors patient is analogous to an accelerating Cachexia can occur in the absence of car running out of petrol. The anorexia anorexia, suggesting that catabolic fatigue component of cancer cachexia reduces mediators produced by tumour or host fuel supply (by ca 300–500 kcal/day) cells are involved in the cancer cachexia whilst accelerated metabolic cycling Grant D Stewart BSc(Hons) MBChB MRCS(Ed), process.9 Experimental cachexia models drives hypermetabolism (by ca Surgical Research Fellow suggest pro-inflammatory cytokines, 100–200 kcal/day). There are also the Richard JE Skipworth BSc(Hons) MBChB such as tumour necrosis factor- , inter- direct catabolic effects of muscle proteol- α MRCS(Ed), Surgical Research Fellow leukin (IL)-6, IL-1 and interferon- , can ysis and lipolysis. These changes underlie γ Kenneth CH Fearon MBChB(Hons) MD all play a role. Activation of the neuro- a key paradox of cachexia: whilst meta- FRCS(Glas) FRCS(Ed) FRCS(Eng), Professor of endocrine stress response is also thought bolic rate may be increased, overall (or Surgical Oncology to be important. Potential mediators total) energy expenditure is decreased Department of Clinical and Surgical Sciences include increased adrenergic activity, ele- due to a fall in physical activity.7 (Surgery), University of Edinburgh, Royal vated cortisol, low insulin and increased Infirmary, Edinburgh activity of the renin-angiotensin system.1 Anorexia With regard to tumour-specific Clin Med 2006;6:140–3 The anorexia component of cancer cachectic factors, proteolysis-inducing cachexia has both a neurohumoral mech- factor (PIF) is produced by tumours and anism due to disturbance of the central excreted in the urine of patients with Background physiological mechanisms controlling cancer cachexia. -

Workforce Prevention and Influenza Illness Policy Guidelines

Workforce Prevention and Influenza Illness Policy Guidelines This document provides guidance to (Company) _________________ supervisors and employees on how to handle influenza-like illness in the (Company) _________________ workplace. OVERVIEW Influenza is a respiratory disease caused by the influenza virus. Influenza is spread primarily person-to-person through coughing, sneezing, or nasal secretions from infected people, or when someone touches something with flu viruses on it before touching their mouths or noses. Infected people can spread the virus to others even before symptoms develop, and can be contagious for several days after becoming sick. Employees experiencing flu-like symptoms such as fever and chills with cough, sore throat, head and muscle ache, nasal congestion and fatigue should not come to work or should leave work to go home. Employees should stay home and avoid contact with other people until they have no symptoms for 24 hours without medication. Employees can plan to return to work 24 hours after fever subsides, without use of fever lowering medications. Supervisors are responsible for ensuring their staff members to stay away from work when experiencing influenza-like illness. Employees have a duty to practice healthy hygiene habits to prevent the spread of disease, and an expectation of working in an environment free of influenza-like illness. Those with severe symptoms, such as difficulty breathing, or at higher risk for complication from influenza should call their health care provider. If you are an employee who is experiencing flu-like symptoms: • Inform your supervisor that you are experiencing flu-like symptoms and leave the workplace as soon as possible. -

Hyperhidrosis: Anatomy, Pathophysiology and Treatment with Emphasis on the Role of Botulinum Toxins

Toxins 2013, 5, 821-840; doi:10.3390/toxins5040821 OPEN ACCESS toxins ISSN 2072-6651 www.mdpi.com/journal/toxins Review Hyperhidrosis: Anatomy, Pathophysiology and Treatment with Emphasis on the Role of Botulinum Toxins Amanda-Amrita D. Lakraj 1, Narges Moghimi 2 and Bahman Jabbari 1,* 1 Department of Neurology, Yale University School of Medicine; New Haven, CT 06520, USA; E-Mail: [email protected] 2 Department of Neurology, Case Western Reserve University; Cleveland, OH 44106, USA; E-Mail: [email protected] * Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-203-737-2464; Fax: +1-203-737-1122. Received: 12 February 2013; in revised form: 27 March 2013 / Accepted: 12 April 2013 / Published: 23 April 2013 Abstract: Clinical features, anatomy and physiology of hyperhidrosis are presented with a review of the world literature on treatment. Level of drug efficacy is defined according to the guidelines of the American Academy of Neurology. Topical agents (glycopyrrolate and methylsulfate) are evidence level B (probably effective). Oral agents (oxybutynin and methantheline bromide) are also level B. In a total of 831 patients, 1 class I and 2 class II blinded studies showed level B efficacy of OnabotulinumtoxinA (A/Ona), while 1 class I and 1 class II study also demonstrated level B efficacy of AbobotulinumtoxinA (A/Abo) in axillary hyperhidrosis (AH), collectively depicting Level A evidence (established) for botulinumtoxinA (BoNT-A). In a comparator study, A/Ona and A/Inco toxins demonstrated comparable efficacy in AH. For IncobotulinumtoxinA (A/Inco) no placebo controlled studies exist; thus, efficacy is Level C (possibly effective) based solely on the aforementioned class II comparator study. -

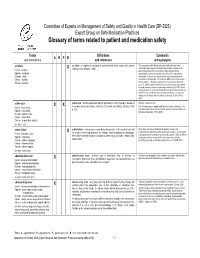

Glossary of Terms Related to Patient and Medication Safety

Committee of Experts on Management of Safety and Quality in Health Care (SP-SQS) Expert Group on Safe Medication Practices Glossary of terms related to patient and medication safety Terms Definitions Comments A R P B and translations and references and synonyms accident accident : an unplanned, unexpected, and undesired event, usually with adverse “For many years safety officials and public health authorities have Xconsequences (Senders, 1994). discouraged use of the word "accident" when it refers to injuries or the French : accident events that produce them. An accident is often understood to be Spanish : accidente unpredictable -a chance occurrence or an "act of God"- and therefore German : Unfall unavoidable. However, most injuries and their precipitating events are Italiano : incidente predictable and preventable. That is why the BMJ has decided to ban the Slovene : nesreča word accident. (…) Purging a common term from our lexicon will not be easy. "Accident" remains entrenched in lay and medical discourse and will no doubt continue to appear in manuscripts submitted to the BMJ. We are asking our editors to be vigilant in detecting and rejecting inappropriate use of the "A" word, and we trust that our readers will keep us on our toes by alerting us to instances when "accidents" slip through.” (Davis & Pless, 2001) active error X X active error : an error associated with the performance of the ‘front-line’ operator of Synonym : sharp-end error French : erreur active a complex system and whose effects are felt almost immediately. (Reason, 1990, This definition has been slightly modified by the Institute of Medicine : “an p.173) error that occurs at the level of the frontline operator and whose effects are Spanish : error activo felt almost immediately.” (Kohn, 2000) German : aktiver Fehler Italiano : errore attivo Slovene : neposredna napaka see also : error active failure active failures : actions or processes during the provision of direct patient care that Since failure is a term not defined in the glossary, its use is not X recommended. -

“Take 3” Actions to Fight The

Flu is a serious Flu-like symptoms include: contagious disease ■ fever that can lead to ■ cough hospitalization. ■ sore throat ■ runny or stuffy nose ■ body aches ■ headache CDC Says ■ chills ■ fatigue “ Take 3” Some people also may have vomiting and diarrhea. People Actions may be infected with the flu, To Fight The Flu and have respiratory symptoms without a fever. For more information, visit Department of Health and www.cdc.gov/flu Human Services or call 800-CDC-INFO. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention September 2014 CS251488-A CDC urges you to take the following actions to protect yourself and others from influenza (the flu): # Take time # Take everyday preventive # Take flu antiviral 1 to get 2 actions to stop the 3 drugs if your doctor a flu vaccine. spread of germs. prescribes them. ■ CDC recommends a yearly flu vaccine as the first and ■ Try to avoid close contact with sick people. ■ If you get the flu, antiviral drugs can treat most important step in protecting against flu viruses. your illness. ■ If you are sick with flu-like illness, CDC recommends ■ While there are many different flu viruses, the flu that you stay home for at least 24 hours after ■Antiviral drugs are different from antibiotics. vaccine protects against the viruses that research your fever is gone except to get medical care or They are prescription medicines (pills, liquid suggests will be most common. for other necessities. Your fever should be gone or an inhaled powder) and are not available without the use of a fever-reducing medicine. over-the-counter. -

History & Physical Format

History & Physical Format SUBJECTIVE (History) Identification name, address, tel.#, DOB, informant, referring provider CC (chief complaint) list of symptoms & duration. reason for seeking care HPI (history of present illness) - PQRST Provocative/palliative - precipitating/relieving Quality/quantity - character Region - location/radiation Severity - constant/intermittent Timing - onset/frequency/duration PMH (past medical /surgical history) general health, weight loss, hepatitis, rheumatic fever, mono, flu, arthritis, Ca, gout, asthma/COPD, pneumonia, thyroid dx, blood dyscrasias, ASCVD, HTN, UTIs, DM, seizures, operations, injuries, PUD/GERD, hospitalizations, psych hx Allergies Meds (Rx & OTC) SH (social history) birthplace, residence, education, occupation, marital status, ETOH, smoking, drugs, etc., sexual activity - MEN, WOMEN or BOTH CAGE Review Ever Feel Need to CUT DOWN Ever Felt ANNOYED by criticism of drinking Ever Had GUILTY Feelings Ever Taken Morning EYE OPENER FH (family history) age & cause of death of relatives' family diseases (CAD, CA, DM, psych) SUBJECTIVE (Review of Systems) skin, hair, nails - lesions, rashes, pruritis, changes in moles; change in distribution; lymph nodes - enlargement, pain bones , joints muscles - fractures, pain, stiffness, weakness, atrophy blood - anemia, bruising head - H/A, trauma, vertigo, syncope, seizures, memory eyes- visual loss, diplopia, trauma, inflammation glasses ears - deafness, tinnitis, discharge, pain nose - discharge, obstruction, epistaxis mouth - sores, gingival bleeding, teeth, -

Guiding Principles for the Diagnosis of Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome

Guiding Principles for the Diagnosis of Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome The following document is based on input and feedback obtained from a panel of experts using a modified Delphi panel process. These experts were engaged by the Centre for Effective Practice on behalf of the Minis- try of Health and Long-Term Care.1 The following principles represent a suggested approach for the diagnosis of Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS) in primary care, based on available literature and expert opinion. This resource is intended to help primary care providers diagnose and treat patients with ME/CFS. The key features of ME/CFS are: Fatigue Post-Exertional Malaise • New/defined onset • Worsening of symptoms (e.g. soreness, feeling drained or sick) resulting from minimal physical, • Persistent mental, or cognitive exertion • Not resulting from other diagnoses, medical • Episodes of immobilizing post-exertional physical and/ problems, medications or mental fatigue and/or malaise • Accompanied by malaise and a range of other symptoms Consensus was achieved among the panel to support the use of the Canadian Consensus Definition for ME/ CFS2 or the Institute of Medicine 2015 Criteria for the Diagnosis of ME/CFS.3 Providers may consider using one, or both, of these resources in supporting their diagnosis, depending on their familiarity with ME/CFS.4 Providers may also consider the following in diagnosing patients using these definitions: • Orthostatic intolerance, as listed in the Institute of Medicine definition, may be present in patients but is not essential for a diagnosis of ME/CFS. Similarly, some symptoms listed in the Canadian Consensus Definition (i.e. -

Getting Help for Fatigue

Getting Help for Fatigue Fatigue is an extreme feeling of tiredness or lack of energy, often described as being exhausted. Fatigue is something that lasts even when a person seems to be getting enough sleep. Cancer-related fatigue is one of the most common side effects of cancer and its treatment. What causes fatigue in people with cancer? Describing fatigue Cancer can cause fatigue. It is also very common You can describe your level of fatigue as none, mild, with cancer treatments, such as chemo and radiation moderate, or severe. Or you can use a scale of 0 to 10, therapy. Other things that may cause fatigue are having where 0 means no fatigue at all, and 10 means the worst and recovering from surgery, low blood counts or fatigue you can imagine. low electrolyte (blood chemistry) levels, infection, or You may be asked questions like: changes in hormone levels. • When did the fatigue start? How long has it lasted? Talking about your fatigue • Has it changed over time? In what way? Feeling weakness or fatigue is common in people with • Does anything make it better? Worse? cancer, but it’s different for each person. The best way • How has it affected what you do every day or the to help your health care team know the type of fatigue things that bring meaning to your life? you are feeling is from your own report of your own fatigue. But fatigue can be hard to describe. Tips to manage fatigue People describe fatigue in many ways. Some say they Save your energy feel tired, weak, exhausted, weary, worn out, or slow. -

HISTORY of PRESENT ILLNESS ELEMENTS: Location Timing Quality Context Severity Modifying Factors Duration Associated Signs/Symptoms

HISTORY OF PRESENT ILLNESS ELEMENTS: Location Timing Quality Context Severity Modifying Factors Duration Associated Signs/Symptoms REVIEW OF SYSTEMS (ROS): Constitutional Integumentary (skin and/or breast) Eyes Neurological ENT, including mouth Psychiatric Cardiovascular Endocrine Genitourinary Respiratory Gastrointestinal Hematologic/Lymphatic Musculoskeletal Allergic/Immunologic PHYSICAL EXAM: BODY AREAS: ORGAN SYSTEMS: Head (including face) Constitutional Musculoskeletal Neck Eyes Skin Chest (including Breasts & ENT and mouth Neurologic Axillae) Abdomen Cardiovascular Psychiatric Genitalia, groin, buttocks Respiratory Hematologic/ Back (including spine) Gastrointestinal Lymphatic/ Each Extremity Genitourinary Immunologic 1995 coding guidelines count Body Areas and/or Organ Systems 1997 coding guidelines count bullets from General Multi-System Examination or Single Organ System Exam HPI/ROS HPI: History of Present Illness Location: where in/on the body the problem, symptom or pain occurs, eg. Area of body, bilateral, unilateral, left, right, anterior, posterior, upper, lower, diffuse or localized, fixed or migratory, radiating to other areas. Quality: an adjective describing the type of problem, symptom or pain, eg. Dull, sharp, throbbing, constant, intermittent, itching, stabbing, acute, chronic, improving or worsening, red or swollen, cramping shooting, scratchy Severity: patient’s nonverbal actions or verbal description as to the degree/extent of the problem, symptom or pain: pain scale 0 to 10, comparison of the current problem, symptom or pain to previous experiences, severity itself is considered a quality. Duration: how long the problem, symptom or pain has been present or how long the problem, symptom or pain lasts, eg. Since last night, for the past week, until today, it lasted for 2 hours Timing: describes when the pain occurs eg. -

Review of Systems

Warren E. Hill, MD, FACS Neal A. Nirenberg, MD, FACS East Valley Ophthalmology, Ltd. Diplomate, American Board of Ophthalmology Diplomate, American Board of Ophthalmology 5620 E. Broadway Road Diplomate, American Board of Eye Surgery Cataract and Comprehensive Ophthalmology Mesa, Arizona 85206-1438 Cataract and Anterior Segment Surgery Telephone: (480) 981-6111 Facsimile: (480) 985-2426 Jonathan B. Kao, MD Yuri F. McKee, MD Internet www.doctor-hill.com Diplomate, American Board of Ophthalmology Diplomate, American Board of Ophthalmology Cataract, Cornea and External Disease Cataract, Cornea and Anterior Segment Surgery Glaucoma Surgery and Management Review of Systems For new patients, established patients who may be having new problems, or patients we have not seen in a while, we need to update your overall medical health. In each area, if you are not having any difficulties please circle No problems. If you are experiencing any of the symptoms listed, please circle the ones that apply, or you may write in ones that may not be listed. If you have any questions, please ask one of our staff. Cardiovascular Ears/Nose/Throat Musculoskeletal Respiratory Chest pain Dizziness Back pain Cough Irregular heartbeat Hearing loss Joint pain Trouble breathing Shortness of breath Hoarseness Muscle aches Wheezing ________________ Ringing in ears Stiffness ________________ Sore throat Swelling ________________ ________________ No problems No problems No problems No problems Constitutional Hematologic Neurologic Skin Fatigue Bleeding Balance problems -

Could It Be Early Hiv? Diarrhea Tired Feeling Swollen Glands

SORE THROAT RASHMOUTH SORES TONSILLITIS COULD IT BE EARLY HIV? DIARRHEA TIRED FEELING SWOLLEN GLANDS JOINTFEVER AND MUSCLE ACHES RASH COULD IT BE EARLY HIV? Early/Acute Early HIV is the beginning stage of HIV, right after someone gets the virus. If you were not aware that your partner is living with HIV, you did not realize you were at risk. During early HIV, the virus is reproducing very rapidly and HIV can be easily passed to others through sex or sharing injection equipment. Early HIV is sometimes called acute HIV. Signs and Symptoms of Acute/Early HIV • Sore throat • Swollen glands • Fever • Rash • Joint and muscle aches • Diarrhea • Tired feeling • Tonsillitis • Mouth sores The signs and symptoms of acute HIV can begin 2 to 4 weeks after you are diagnosed as living with HIV. Symptoms can last for just a few days or weeks. In rare cases, they could last for several months. The signs and symptoms of early HIV are similar to the signs and symptoms of other common illnesses like the flu, cold, sore throat or mononucleosis. 1 COULD IT BE EARLY HIV? Is it the flu or Early/Acute HIV? The symptoms of early HIV and the flu are similar but not the same. Flu and Early HIV Symptoms Fever • Fatigue • Muscle aches Headaches • Sore throat • Swollen lymph nodes If you have these symptoms you may have the flu: Flu Symptoms Nasal congestion • Cough • Sneezing If you have these symptoms you may have early/acute HIV: Early HIV Symptoms Rash • Mouth Sores If you are not sure if you have the flu or early HIV, ask yourself the questions below.