The Hamilton Rapid Transit Plans That Could Have Been

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SPECIAL GENERAL ISSUES COMMITTEE LIGHT RAIL TRANSIT (LRT) MINUTES 16-026 10:30 A.M

SPECIAL GENERAL ISSUES COMMITTEE LIGHT RAIL TRANSIT (LRT) MINUTES 16-026 10:30 a.m. Tuesday, October 25, 2016 Council Chambers Hamilton City Hall 71 Main Street West ______________________________________________________________________ Present: Mayor F. Eisenberger, Deputy Mayor D. Skelly (Chair) Councillors T. Whitehead, T. Jackson, C. Collins, S. Merulla, M. Green, J. Farr, A. Johnson, D. Conley, M. Pearson, B. Johnson, L. Ferguson, R. Pasuta, J. Partridge Absent with Regrets: Councillor A. VanderBeek – Personal _____________________________________________________________________ THE FOLLOWING ITEMS WERE REFERRED TO COUNCIL FOR CONSIDERATION: 1. Light Rail Transit (LRT) Project Update (PED16199) (City Wide) (Item 5.1) (Conley/Pearson) That Report PED16199, respecting the Light Rail Transit (LRT) Project Update, be received. CARRIED 2. Hamilton Street Railway (HSR) Fare Integration (PW16066) (City Wide) (Item 6.1) (Eisenberger/Ferguson) That Report PW16066, respecting Hamilton Street Railway (HSR) Fare Integration, be received. CARRIED 3. Possibility of adding the LRT A-Line at the same time as building the B- Line (7.2) (Merulla/Whitehead) That staff be directed to communicate with Metrolinx to determine the possibility of adding the LRT A-Line at the same time as building the B-Line and report back to the LRT Sub-Committee. CARRIED General Issues Committee October 25, 2016 Minutes 16-026 Page 2 of 26 4. LRT Project Not to Negatively Affect Hamilton’s Allocation of Provincial Gas Tax Revenue or Future Federal Infrastructure Public Transit Funding (Item 7.3) (Collins/Merulla) That the Province of Ontario be requested to commit that the Hamilton Light Rail Transit (LRT) Project will not negatively affect Hamilton’s allocation of Provincial Gas Tax Funding or Future Federal Infrastructure Public Transit Funding. -

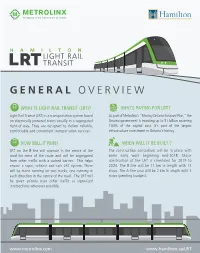

General Overview

HAMILTON LIGHT RAIL LRT TRANSIT GENERAL OVERVIEW WHAT IS LIGHT RAIL TRANSIT (LRT)? WHO’S PAYING FOR LRT? Light Rail Transit (LRT) is a transportation system based As part of Metrolinx’s “Moving Ontario Forward Plan,” the on electrically powered trains usually in a segregated Ontario government is investing up to $1 billion covering right-of-way. They are designed to deliver reliable, 100% of the capital cost. It’s part of the largest comfortable and convenient transportation services. infrastructure investment in Ontario's history. HOW WILL IT RUN? WHEN WILL IT BE BUILT ? LRT on the B-line will operate in the centre of the The construction consortium will be in place with road for most of the route and will be segregated some early work beginning mid-2018. Major from other traffic with a curbed barrier. This helps construction of the LRT is scheduled for 2019 to ensure a rapid, reliable and safe LRT system. There 2024. The B-line will be 11 km in length with 13 will be trains running on two tracks; one running in stops. The A-line spur will be 2 km in length with 5 each direction in the centre of the road. The LRT will stops (pending budget). be given priority over other traffic at signalized intersections wherever possible. www.metrolinx.com www.hamilton.ca/LRT WHERE WILL THE LRT RUN? WHAT ARE THE BENEFITS OF LRT? HOW OFTEN WILL IT RUN? LRT will provide Hamilton with fast, reliable, convenient The trains will run approximately every five minutes and integrated transit, including connections to the during peak hours. -

His Worship Mayor Fred Eisenberger, City of Hamilton, and Members of Hamilton City Council Hamilton, Ontari

5.18 March 21, 2017 To: His Worship Mayor Fred Eisenberger, City of Hamilton, And Members of Hamilton City Council Hamilton, Ontario Dear Mayor Eisenberger and Members of Hamilton City Council, As anchor institutions in Hamilton, we believe in the transformative potential of a robust transit system, including both traditional and rapid transit, for the health and prosperity of our city. We support the full implementation of Hamilton’s BLAST network that will enable our students, our patients, our employees, and our citizens to benefit from improved mobility within our city and a wider variety of transit options. To this end, we urge the City of Hamilton to continue with the implementation of the BLAST transit network. We gratefully acknowledge and value our provincial government’s leadership in funding for the Light Rail Transit B-line and Bus Rapid Transit A-line as key components of the BLAST network. We fully support the staged completion of the BLAST network and the collaboration of all levels of government to complete this project together. Sincerely, David Hansen Sean Donnelly Director of Education, President and CEO, Hamilton Wentworth Catholic ArcelorMittal Dofasco District School Board Manny Figueiredo Keanin Loomis Director of Education, CEO, Hamilton Chamber Hamilton-Wentworth District of Commerce School Board Terry Cooke Patrick Deane President & CEO, Hamilton President & Vice Chancellor, Community Foundation McMaster University Rob MacIsaac Ron J. McKerlie President & CEO, President, Hamilton Health Sciences Mohawk College Howard Elliot Dr. David A. Higgins Chair, Hamilton Roundtable President, St. Joseph’s for Poverty Reduction Healthcare Hamilton. -

Please Sign in So We Can Provide Updates and Information on Future Events

HURONTARIO LIGHT RAIL TRANSIT PROJECT Welcome Please sign in so we can provide updates and information on future events. metrolinx.com/HurontarioLRT [email protected] @HurontarioLRT WHAT IS THE HURONTARIO LRT PROJECT? The Hurontario Light Rail Transit (LRT) Project will bring 20 kilometres of fast, reliable, rapid transit to the cities of Mississauga and Brampton along the Hurontario corridor. New, modern light rail vehicles will travel in a dedicated right-of-way and serve 22 stops with connections to GO Transit’s Milton and Lakeshore West rail lines, Mississauga MiWay, Brampton Züm, and the Mississauga Transitway. Metrolinx is working in coordination with the cities of Mississauga and Brampton and the Region of Peel to advance the Hurontario LRT project. Preparatory construction is underway. The project is expected to be completed at the end of 2022. The Hurontario LRT project is funded through a $1.4 billion commitment from the Province of Ontario as part of the Moving Ontario Forward plan. Allandale LAKE SIMCOE Waterfront OUR RAPID TRANSIT NETWORK Barrie South Innisfil SIMCOE Bradford East Gwillimbury Newmarket NewmarketSouthlakeHuron Heights Leslie TODAY AND TOMORROW GO Bus Terminal Hwy 404 Eagle LEGEND Mulock Main Mulock Savage Longford Aurora Lincolnville Every train, subway and bus helps to keep us moving, connecting us to the people and places Bloomington King City Stouffville GO Rail that matter most. As our region grows, our transit system is growing too. Working with 19th- Gamble Bernard Gormley municipalities across the Greater Toronto and Hamilton Area, and beyond, we’re delivering Kirby Elgin Mills Mount Joy Crosby Centennial new transit projects,making it easier, better, and faster for you to get around. -

Canadian Version

OFFICIAL JOURNAL OF THE AMALGAMATED TRANSIT UNION | AFL-CIO/CLC JULY / AUGUST 2014 A NEW BEGINNING FOR PROGRESSIVE LABOR EDUCATION & ACTIVISM ATU ACQUIRES NATIONAL LABOR COLLEGE CAMPUS HAPPY LABOUR DAY INTERNATIONAL OFFICERS LAWRENCE J. HANLEY International President JAVIER M. PEREZ, JR. NEWSBRIEFS International Executive Vice President OSCAR OWENS TTC targets door safety woes International Secretary-Treasurer Imagine this: your subway train stops at your destination. The doors open – but on the wrong side. In the past year there have been INTERNATIONAL VICE PRESIDENTS 12 incidents of doors opening either off the platform or on the wrong side of the train in Toronto. LARRY R. KINNEAR Ashburn, ON – [email protected] The Toronto Transit Commission has now implemented a new RICHARD M. MURPHY “point and acknowledge” safety procedure to reduce the likelihood Newburyport, MA – [email protected] of human error when opening train doors. The procedure consists BOB M. HYKAWAY of four steps in which a subway operator must: stand up, open Calgary, AB – [email protected] the window as the train comes to a stop, point at a marker on the wall using their index finger and WILLIAM G. McLEAN then open the train doors. If the operator doesn’t see the marker he or she is instructed not to open Reno, NV – [email protected] the doors. JANIS M. BORCHARDT Madison, WI – [email protected] PAUL BOWEN Agreement in Guelph, ON, ends lockout Canton, MI – [email protected] After the City of Guelph, ON, locked out members of Local 1189 KENNETH R. KIRK for three weeks, city buses stopped running, and transit workers Lancaster, TX – [email protected] were out of work and out of a contract while commuters were left GARY RAUEN stranded. -

Randle Reef Sediment Remediation Project

Randle Reef Sediment Remediation Project Comprehensive Study Report Prepared for: Environment Canada Fisheries and Oceans Canada Transport Canada Hamilton Port Authority Prepared by: The Randle Reef Sediment Remediation Project Technical Task Group AECOM October 30, 2012 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The Randle Reef Sediment Remediation Project Technical Task Group Members: Roger Santiago, Environment Canada Erin Hartman, Environment Canada Rupert Joyner, Environment Canada Sue-Jin An, Environment Canada Matt Graham, Environment Canada Cheriene Vieira, Ontario Ministry of Environment Ron Hewitt, Public Works and Government Services Canada Bill Fitzgerald, Hamilton Port Authority The Technical Task Group gratefully acknowledges the contributions of the following parties in the preparation and completion of this document: Environment Canada, Fisheries and Oceans Canada, Transport Canada, Hamilton Port Authority, Health Canada, Public Works and Government Services Canada, Ontario Ministry of Environment, Canadian Environmental Assessment Act Agency, D.C. Damman and Associates, City of Hamilton, U.S. Steel Canada, National Water Research Institute, AECOM, ARCADIS, Acres & Associated Environmental Limited, Headwater Environmental Services Corporation, Project Advisory Group, Project Implementation Team, Bay Area Restoration Council, Hamilton Harbour Remedial Action Plan Office, Hamilton Conservation Authority, Royal Botanical Gardens and Halton Region Conservation Authority. TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................................................. -

A Tale of 40 Cities: a Preliminary Analysis of Equity Impacts of COVID-19 Service Adjustments Across North America July 2020 Mc

A tale of 40 cities: A preliminary analysis of equity impacts of COVID-19 service adjustments across North America James DeWeese, Leila Hawa, Hanna Demyk, Zane Davey, Anastasia Belikow, and Ahmed El-Geneidy July 2020 McGill University Abstract To cope with COVID-19 confinement measures and precipitous declines in ridership, public transport agencies across North America have made significant adjustments to their services, slashing trip frequency in many areas while increasing it in others. These adjustments, especially service cuts, appear to have disproportionately affected areas where lower income and more- vulnerable groups reside in North American Cities. This paper compares changes in service frequency across 30 U.S. and 10 Canadian cities, linking these changes to average income levels and a vulnerability index. The study highlights the wide range of service outcomes while underscoring the potential for best practices that explicitly account for vertical equity, or social justice, in their impacts when adjusting service levels. Research Question and Data Public transport ridership in North American Cities declined dramatically by the end of March 2020 as governments applied confinement measures in response to COVID-19 pandemic (Hart, 2020; Vijaya, 2020). In an industry that depends heavily on fare-box recovery to pay for operations and sometimes infrastructure loans (Verbich, Badami, & El-Geneidy, 2017), transport agencies faced major financial strains, even as the pandemic magnified their role as a critical public service, ferrying essential, often low-income, workers with limited alternatives to their jobs (Deng, Morissette, & Messacar, 2020). Public transport agencies also faced major operating difficulties due to absenteeism among operators (Hamilton Spectator, 2020) and enhanced cleaning protocols. -

Library Usage and Demographics Study Report 2018

Library use across Hamilton: Borrowing and population trends for library planning FINAL Prepared for the Hamilton Public Library June 2018 Prepared by Sara Mayo Social Planning and Research Council of Hamilton 350 King St East, Suite 104, Hamilton, ON L8N 3Y3 www.sprc.hamilton.on.ca Social Planning and Research Council of Hamilton – HPL report (Final Draft) page 2 Table of Contents 1.0 Introduction ........................................................................................................................ 5 2.0 Data and methods .............................................................................................................. 8 3.0 Hamilton’s population growth patterns ........................................................................ 10 3.1. Growth at ward and sub-ward level areas ..................................................................... 10 3.2. Projected population per branch in 2025 ....................................................................... 13 3.3. Additional city of Hamilton growth planning context ...................................................... 15 4.0 Branch performance metrics.......................................................................................... 18 4.1. Performance metrics by branch characteristiscs, assets and locations ....................... 18 4.2. Branch circulation performance by time periods ........................................................... 23 5.0 Population characteristics, cardholders and circulation performance metrics ..... 24 5.1. -

Public Works Department

5.1 2016 TAX OPERATING BUDGET PUBLIC WORKS DEPARTMENT General Issues Committee February 1, 2016 Public Works Department 2016 Budget 2016 TAX OPERATING BUDGET Content 1. Department Overview 2. Transit (10 Year Plan) 3. ATS Delivery Alternative 4. Divisional Budget Presentations – Transit – Operations – Environmental Services – Corporate Assets & Strategic Planning – Engineering Services 2 Public Works Department 2016 Budget CONTEXT To be the best place in Canada to raise a child, promote VISION innovation, engage citizens and provide diverse economic opportunities 2012-2015 Mission and values STRATEGIC PLAN Strategic Priorities: •#1 Healthy & Prosperous Community STRATEGY •#2 Valued & Sustainable Services •#3 Leadership & Governance Strategic Objectives & Actions PUBLIC WORKS BUSINESS PLAN Providing services that bring our City to life! DEPARTMENT & Front line services: Engineering Services, Strategic Planning, Cemeteries, DIVISION PLANS Forestry, Horticulture, Parks, Roads & Winter Control, Waste Management, Energy Management, Facilities, Fleet, Traffic Engineering and Operations, Transit (ATS & TACTICS HSR), Transportation Management, Storm Water, Water & Wastewater, Waterfront Development Influencing Factors: Aging infrastructure, energy costs, service levels, legislation, contracts, collective bargaining agreements, master plans, development and growth, weather and seasonal demands, emergency response, climate change, public expectations, Pan Am Games………. 3 Public Works Department 2016 Budget OVERVIEW FCS16001 Book 2, Page 112 Purpose -

Accessible Transit Services (ATS) Review (PW05075(A)) (City Wide)

CITY WIDE IMPLICATIONS CITY OF HAMILTON ACCESSIBLE TRANSIT SERVICES (ATS) STEERING COMMITTEE Report to: Mayor and Members Submitted by: Councillor Terry Whitehead Chair Committee of the Whole ATS Steering Committee Date: June 15, 2006 Prepared by: Connie Wheeler Extension 5779 SUBJECT: Accessible Transit Services (ATS) Review - (PW05075a) - (City Wide) RECOMMENDATION: (a) That a Task Force be established to review improvements, look for efficiencies and make recommendations quarterly, to the General Manager of Public Works respecting Accessible Transit Services. (b) That the Accessible Transit Services governance structure attached as Appendix A to Report PW05075(a), be approved for a period of three months upon Council approval, at which time the Accessible Transit Services Steering Committee will reconvene to determine the appropriateness of the new model and/or revise the model based on a report from the Task Force outlining their initial success or further recommendations. (c) That the above results be incorporated into a competitive RFP process which will be compiled in 2007 with the approved vendor(s) beginning work in 2008. (d) That the City program be re-branded which, in turn, would allow both DARTS and Vets the opportunity to individually brand their services. (e) That there are to be no additional costs as a result of any changes made to the program. (f) That any savings be applied to enhancing the service. (g) That a Business Analyst (Trapeze software) be hired, subject to acceptance of this review (currently in Budget, awaiting conclusion of review). (h) That the Director of Transit and the Manager of Transit Fare Administration & ATS be reaffirmed as Public Works staff representatives on the DARTS Board of Directors as non-voting members. -

Cootes Drive

Cootes Drive By: Aaron Burton For Dundas Turtle Watch 1/5/2020 CASE STUDY #1 COOTES DRIVE A major travel route in Dundas since the mid-1930s1, Cootes Drive stretches across over three kilometers of land. It connects the heart of Dundas to Main Street in Hamilton, enabling access to York Road, Highways 5 & 6, and, of course, McMaster University and Hospital. HOW FAST?! Aside from being built through an ecologically sensitive wetland, which probably was not a main issue in the 30s, there is another interesting thing about Cootes Drive. Drivers start and finish going the standard 50km/h, but they enjoy a thrill at 80km/h across most of the mid-section. Just for some perspective, this is the same speed that is allowed on the Red Hill Valley Parkway! In 2019, the speed limit was reduced from 90km/h on the RHVP due to the number of traffic accidents and potential driving hazards. Since local endangered wildlife is seen neither as victims nor driving hazards, vehicles are still allowed to zip up and down Cootes Drive. It is true – there are no homes, only one controlled intersection, and pedestrian traffic is safely shielded by a chain-link fence on a portion of the road; however, the fact remains that Cootes Drive is still only an arterial road in Dundas, not a major throughway. During walks along Spencer Creek, there are many evenings in the summer months when, upon getting the green light, vehicles can be heard accelerating up the hill, and instinct informs that they are going well above the already excessive 80km/h. -

General Issues Committee Agenda Package

City of Hamilton GENERAL ISSUES COMMITTEE REVISED Meeting #: 19-004 Date: February 20, 2019 Time: 9:30 a.m. Location: Council Chambers, Hamilton City Hall 71 Main Street West Stephanie Paparella, Legislative Coordinator (905) 546-2424 ext. 3993 Pages 1. CEREMONIAL ACTIVITIES 1.1 Vic Djurdjevic - Tesla Medal Awarded, by the Tesla Science Foundation United States, to the City of Hamilton in Recognition of the City Support and Recognition of Nikola Tesla (no copy) 2. APPROVAL OF AGENDA (Added Items, if applicable, will be noted with *) 3. DECLARATIONS OF INTEREST 4. APPROVAL OF MINUTES OF PREVIOUS MEETING 4.1 February 6, 2019 5 5. COMMUNICATIONS 6. DELEGATION REQUESTS 6.1 Tim Potocic, Supercrawl, to outline the current impact of the Festival to 35 the City of Hamilton (For the March 20, 2019 GIC) 6.2 Ed Smith, A Better Niagara, respecting the Niagara Peninsula 36 Conservation Authority (NPCA) (For the March 20, 2019 GIC) Page 2 of 198 7. CONSENT ITEMS 7.1 Barton Village Business Improvement Area (BIA) Revised Board of 37 Management (PED19037) (Wards 2 and 3) 7.2 Residential Special Event Parking Plan for the 2019 Canadian Open Golf 40 Tournament (PED19047) (Ward 12) 7.3 Public Art Master Plan 2016 Annual Update (PED19053) (City Wide) 50 8. PUBLIC HEARINGS / DELEGATIONS 8.1 Vic Djurdjevic, Nikola Tesla Educational Corporation, respecting the Tesla Educational Corporation Events and Activities (no copy) 9. STAFF PRESENTATIONS 9.1 2018 Annual Report on the 2016-2020 Economic Development Action 64 Plan Progress (PED19036) (City Wide) 10. DISCUSSION