The Contribution of Autobiography and Literature to the Understanding of Tourette Syndrome

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ell Inventory

1/20/2020 ELL 3747 BOOKS 1-Fiction A B C D 1 FICTION Author Categor 2 Fever, The Abbott, Megan Fiction 3 Mycroft Holmes Abdul-Jabbar, Kareem Fiction 4 Lost Diary of Don Juan, The Abrams, Douglas Carlton Fiction 5 Things Fall Apart Achebe, Chinua Fiction 6 Last Lovely City, The (stories) Adams, Alice Fiction 7 Saint Croix Notes Adams, Noah Fiction 8 Girl in a Swing, The Adams, Richard Fiction 9 Americanah Adichie, C.N. Fiction 10 White Tiger, The Adiga, Aravind Fiction 11 Secret of the Villa Mimosa, The Adler, Elizabeth Fiction 12 Orestean Trilogy, The Aeschylus Fiction 13 Say You're One of Them Akpan, Uwen Fiction 14 American Dream and The Zoo Story Albee, Edward Fiction 15 Everything in the Garden Albee, Edward Fiction 16 Sandbox and Death of Bessie Smith Albee, Edward Fiction 17 Tiny Alice Albee, Edward Fiction 18 Who's Afraid of Virginia Wolf Albee, Edward Fiction 19 Caracol Beach Alberto, Eliseo Fiction 20 Long Fatal Love Chase, A Alcott, Louisa May Fiction 21 Lone Ranger and Tonto Fist Fight, The Alexis, Sherman Fiction 22 Garden Spells (1 of 2 Large Print novels) Allen, Sarah Addison Fiction 23 Daughter of Fortune Allende, Isabel Fiction 24 Eva Luna Allende, Isabel Fiction 25 Inés of My Soul Allende, Isabel Fiction 26 Japanese Lover, The Allende, Isabel Fiction 27 Stories of Eva Luna, The Allende, Isabel Fiction 28 Bastard Out of Carolina Allison, Dorothy Fiction 29 How the Garcia Girls Lost Their Accents Alvarez, Julia Fiction 30 Time of the Butterflies, In the Alverez, Julia Fiction 31 Levanter, The Ambler, Eric Fiction 32 Information, The Amis, Martin Fiction 33 Information, The Amis, Martin Fiction 34 London Fields Amis, Martin Fiction 35 Night Train Amis, Martin Fiction 36 Cuentos Chicanos Anaya, Rudolfo A. -

ŞEHİRLEŞME, TÜRK EDEBİYATI Ve YENİ ŞEHİRLİLER: 1950-1980

FROM MOTHERLESS BROOKLYN TO ÖKSÜZ BROOKLYN: TRANSLATING THE STYLE OF JONATHAN LETHEM Burç İdem DİNÇEL Abstract The works of the contemporary American author Jonathan Lethem suggest themselves as a fertile ground for a sound discussion of style during the translation process due to the distinctive style that the author develops in his novels. This study entitled “From Motherless Brooklyn to Öksüz Brooklyn: Translating the Style of Jonathan Lethem” takes the aforementioned argument as a point of departure, and provides an analysis of the Turkish translation of Motherless Brooklyn from the vantage point of stylistics, as well as from the perspective of the notion of metonymics. In terms of analyzing the style of the target text and source text respectively, this paper benefits from Raymond van den Broeck‟s model so as to develop a descriptive approach. Furthermore, as regards to the notion of metonymics, this paper draws on Maria Tymoczko‟s theoretical writings on the subject in order to demonstrate the metonymic aspects of Motherless Brooklyn, and the second chapter of the novel “Motherless Brooklyn” respectively, with the purpose of setting the ground for a stylistic analysis of the target text through the notion of metonymics. Moreover, by concentrating on the excerpts from “Öksüz Brooklyn”, the article provides a stylistic analysis of Sabri Gürses‟ translation with the intention of offering the chance for the reader to trace the distinctive style of Jonathan Lethem through the Turkish translation of his novel. Key Words: Style, stylistics, metonymics, Jonathan Lethem, decisions in translation. Boğaziçi Üniversitesi Çeviribilim Bölümü Yüksek Lisans Öğrencisi, Çevirmen. 52 Burç İdem DİNÇEL Özet Çağdaş Amerikan yazar Jonathan Lethem‟ın eserleri, yazarın romanlarında geliştirdiği biçem dikkate alındığında, çeviri sürecinde biçem kavramının sahip olabileceği rolü inceleyebilmek açısından verimli bir zemin oluşturmaktadır. -

Not Made for These Times

Faculteit Letteren & Wijsbegeerte Sebastiaan De Vusser Not Made for these Times A Study of Hard-Boiled Identity in Postmodern Literature Masterproef voorgelegd tot het behalen van de graad van Master in de taal- en letterkunde: Engels 2014-2015 Promotor Prof. dr. Philippe Codde Vakgroep Letterkunde 1 Acknowledgements I would like to express my gratitude to my supervisor Prof. dr. Philippe Codde for the useful comments, remarks and engagement through the learning process of this master thesis. I would also like to thank my family for their support during the entire process. In Loving Memory of Jakob Bourgeois, my best friend who died during the making of this thesis. iii Table of Contents Introduction 1 Part 1: Theoretical Approach ................................................................................................................. 3 Chapter 1 The History of the Hard-Boiled Novel ..................................................................... 4 1.1 The Origins of Detective Fiction .............................................................................................. 4 1.2 The Structure of the Traditional Detective Story ..................................................................... 5 1.3 Publication History .................................................................................................................. 6 Chapter 2 The Hard-Boiled Identity ......................................................................................... 9 2.1 The Traditional ‘Tough Guy’ .................................................................................................. -

Transatlantica, 1 | 2019 “I Am a Freak of Nature”: Tourette’S and the Grotesque in Jonathan Lethem’S M

Transatlantica Revue d’études américaines. American Studies Journal 1 | 2019 Gone With the Wind after Gone With the Wind “I am a freak of nature”: Tourette’s and the Grotesque in Jonathan Lethem’s Motherless Brooklyn Pascale Antolin Electronic version URL: https://journals.openedition.org/transatlantica/13941 DOI: 10.4000/transatlantica.13941 ISSN: 1765-2766 Publisher Association française d'Etudes Américaines (AFEA) Electronic reference Pascale Antolin, ““I am a freak of nature”: Tourette’s and the Grotesque in Jonathan Lethem’s Motherless Brooklyn”, Transatlantica [Online], 1 | 2019, Online since 17 July 2020, connection on 03 May 2021. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/transatlantica/13941 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/ transatlantica.13941 This text was automatically generated on 3 May 2021. Transatlantica – Revue d'études américaines est mise à disposition selon les termes de la licence Creative Commons Attribution - Pas d'Utilisation Commerciale - Pas de Modification 4.0 International. “I am a freak of nature”: Tourette’s and the Grotesque in Jonathan Lethem’s M... 1 “I am a freak of nature”: Tourette’s and the Grotesque in Jonathan Lethem’s Motherless Brooklyn Pascale Antolin Certain essential aspects of the world are accessible only to laughter. (Bakhtin, Rabelais 66) 1 “‘Accusatony! Excusebaloney! Funnymonopoly!’ I squeezed my eyes shut to interrupt the seizure of language” (MB1 175). This short passage provides a significant sample of how the hero narrator’s Tourette’s syndrome manifests itself in Jonathan Lethem’s 1999 detective novel, Motherless Brooklyn. “The distinctiveness” of the narrative lies in the “proliferation of Lionel’s verbal tics” (Fleissner 390). While Tourette’s provokes Lionel Essrog’s linguistic outbursts, it breaks and intrudes upon the narrative, introducing dramatic nonsense into the text—even more dramatic when italics are used and the portmanteau words stand out on the page. -

Disability, Literature, Genre: Representation and Affect in Contemporary Fiction REPRESENTATIONS: H E a LT H , DI SA BI L I T Y, CULTURE and SOCIETY

Disability, Literature, Genre: Representation and Affect in Contemporary Fiction REPRESENTATIONS: H E A LT H , DI SA BI L I T Y, CULTURE AND SOCIETY Series Editor Stuart Murray, University of Leeds Robert McRuer, George Washington University This series provides a ground-breaking and innovative selection of titles that showcase the newest interdisciplinary research on the cultural representations of health and disability in the contemporary social world. Bringing together both subjects and working methods from literary studies, film and cultural studies, medicine and sociology, ‘Representations’ is scholarly and accessible, addressed to researchers across a number of academic disciplines, and prac- titioners and members of the public with interests in issues of public health. The key term in the series will be representations. Public interest in ques- tions of health and disability has never been stronger, and as a consequence cultural forms across a range of media currently produce a never-ending stream of narratives and images that both reflect this interest and generate its forms. The crucial value of the series is that it brings the skilled study of cultural narratives and images to bear on such contemporary medical concerns. It offers and responds to new research paradigms that advance understanding at a scholarly level of the interaction between medicine, culture and society; it also has a strong commitment to public concerns surrounding such issues, and maintains a tone and point of address that seek to engage a general audience. -

Diagnostic Methods to Assess the Chronic Impairment

Journal of European Psychology Students, Vol. 3, 2012 The Deconstruction of Gilles de la Tourette’s Syndrome Rowan Voirrey Sandle Contact: [email protected] Abstract The present deconstruction of Gilles de la Tourette’s Syndrome introduces this complex disorder using an existential paradigm. An analysis of the history of constructed reason and power highlights the assumptions of ‘disorder’ that infiltrate society and serves to critique predisposed thought with reference to Tourette’s. The review considers the representationalist theory of language and concepts within psychiatric discourse. A brief analysis of previous case studies shows Tourettic energy as part of the individual ‘self’ and introduces a comparison of Tourettic movement to more mutual human experience, such as music and poetry. Past research that explores preventative social interaction is introduced, which show positive advancements in treatment by challenging the conventions of internal etiology and which highlights the importance of reducing attached stigma. Keywords: Tourette’s Syndrome, Deconstructing psychiatric disorder, social stigma Introduction Echolalia, the mimicking of others vocalizations and palilalia, the repetition of Over a century since its first formal diagnoses one’s own language, have also been reported by the man whose name became the eponym in cases of Tourette’s, as well as the repetition for the condition, Gilles de la Tourette’s of gestures, known as echopraxia. Narrative syndrome remains an enigmatic phenomenon approaches have considered further composite with no consistently identifiable pathology. behaviour as Tourettic, such as a burst of Individuals with the syndrome may encounter energy when playing an instrument (Sacks, clinical misunderstanding (Turtle & 1995; Steingo, 2008). For formal diagnosis, Robertson, 2008, p. -

MOTHERLESS BROOKLYN Written for the Screen by Edward Norton

MOTHERLESS BROOKLYN Written for the Screen by Edward Norton From the Novel by Jonathan Lethem White 1-30-18 Blue Revisions Current Pink Revisions 12-15-18 OVER BLACK LIONEL (V.O.) Frank always used to say: “Tell your story walking, pal...’ INT/EXT LIONEL CAR - HARLEM ST - DAY A beat up ‘54 Dodge sits on a cold Harlem street. Two guys in the front. LIONEL (V.O.) CONT He was more philosophical than your average gumshoe, but he liked to do his talking on the move so... Here’s how it all went down. Close on the TWO GUYS: LIONEL ESSROG and GILBERT CONEY. CONEY is a big lug in a porkpie hat. LIONEL medium build, wiry. Both late 30’s. They don’t look like P.I.’s but that’s what they are. Lionel sits shotgun. He’s a hypnotizing array of Tourettic twitches and tics. LIONEL (V.O.) I got something wrong with my head, that’s the first thing to know LIONEL (yelps) IF! LIONEL (V.O.) It’s like having glass in the brain. I can’t stop picking things apart, twisting em around, words and sounds especially. It’s like an itch that has to be scratched. C.U. A LOOSE THREAD...hanging off the sleeve of a sweater. An arm and a wrist resting on a seated knee. The knee starts to jiggle and then...FINGERS pluck at the thread, try to snap it off then smooth it down. CONEY Quit pullin’ at it. You’re gonna make a fuckin’ mess outta things. -

Eng304bh1x-201209

Emily Russell Carnegie 114 Am Lit Fiction: [email protected] Office Hours: WF 10-11; TR 11:00-12:30 High and Low Culture For English majors, the department has broken up your American literature requirement into two courses: the historical survey (303) and genre study (304). By “genre study,” we mean fiction, poetry, or drama—the long-standing divisions among major classes of literature. But there are cascading definitions of the term genre, and when we speak about “genre fiction” or “genre movies,” we are much more likely to mean the collection of texts that falls under science fiction, detective fiction, fantasy, romance, the western, and horror. Despite strikingly obvious differences in conventions and setting, these texts can be grouped under the umbrella of “genre fiction” because they share features like focus on plot, a turn away from realism, and—above all—mass-market appeal. “Literary fiction,” by contrast, emphasizes craft and meaning, ooften appeals to academic audiences, and is understood as a virtuous endeavor. Genre fiction is trash. Time and tastes change, however. The novel, once considered low art suitable only for women, and “fast” women at that, has a firm place in the academy. Writers like Charles Dickens, Mark Twain, and Edgar Allen Poe who were writing in widely-circulated periodicals are now considered classics. Our most heralded contemporary authors are exploring genre conventions in their award-winning literary fictioon: Colson Whitehead writes about zombies, Michael Chabon writes science fiction, and Cormac McCarthy is doing serial killers and the apocalypse. This course will look at examples of genre fiction, froom the popular archetypes to the high literary experiments. -

![European Journal of American Studies, 3-3 | 2008, “Autumn 2008” [Online], Online Since 09 October 2008, Connection on 08 July 2021](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5080/european-journal-of-american-studies-3-3-2008-autumn-2008-online-online-since-09-october-2008-connection-on-08-july-2021-6135080.webp)

European Journal of American Studies, 3-3 | 2008, “Autumn 2008” [Online], Online Since 09 October 2008, Connection on 08 July 2021

European journal of American studies 3-3 | 2008 Autumn 2008 Electronic version URL: https://journals.openedition.org/ejas/2283 DOI: 10.4000/ejas.2283 ISSN: 1991-9336 Publisher European Association for American Studies Electronic reference European journal of American studies, 3-3 | 2008, “Autumn 2008” [Online], Online since 09 October 2008, connection on 08 July 2021. URL: https://journals.openedition.org/ejas/2283; DOI: https://doi.org/ 10.4000/ejas.2283 This text was automatically generated on 8 July 2021. Creative Commons License 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS From Man of the Crowd to Cybernaut: Edgar Allan Poe’s Transatlantic Journey—and Back. Paul Jahshan ‘The Dream of the Unified Field’: Originality, Influence, the Idea of a National Literature and Contemporary American Poetry Ruediger Heinze The Migration of Tradition: Land Tenure and Culture in the U.S. Upper Mid-West Terje Mikael Hasle Joranger Judas Iscariot: The Archetypal Betrayer and DeMille’s Cine-Biblical Salvation within The King of Kings (1927) Anton Karl Kozlovic “New York and yet not New York”: Reading the Region in Contemporary Brooklyn Fictions James Peacock All Work or No Play: Key Themes in the History of the American Stage Actor as Worker Sean Holmes Zuckerman’s "Blah-blah Blah-blah Blah": a blow to mimesis, a key to irony Arnaud Schmitt “New” “American Studies”: Exceptionalism redux? Marc Chenetier European journal of American studies, 3-3 | 2008 2 From Man of the Crowd to Cybernaut: Edgar Allan Poe’s Transatlantic Journey—and Back. Paul Jahshan The wild effects of the light enchained me to an examination of individual faces; and… it seemed that, in my then peculiar mental state, I could frequently read, even in that brief interval of a glance, the history of long years. -

Ginosko Literary Journal #25 Proof.Docx

1 Ginosko Literary Journal #25 Fall 2020 GinoskoLiteraryJournal.com PO Box 246 Fairfax, CA 94978 Robert Paul Cesaretti, Editor Member CLMP Est. 2002 Writers retain all copyrights Cover Art watercolor found in antique store in Petaluma, CA from Saipan, artist unknown 2 ginosko A Greek word meaning to perceive, understand, realize, come to know; knowledge that has an inception, a progress, an attainment. The recognition of truth from experience. γινώσκω 3 If you are going to be a writer there is nothing I can say to stop you; if you’re not going to be a writer nothing I can say will help you. When you’re writing, you’re trying to find out something which you don’t know. The whole language of writing for me is finding out what you don’t want to know, what you don’t want to find out. But something forces you to anyway. You know it’s finished when you can’t do anything more to it, though it’s never exactly the way you want it. The hardest thing in the world is simplicity. And the most fearful thing, too. You have to strip yourself of all your disguises, some of which you didn’t know you had. You want to write a sentence as clean as a bone. ...discipline, love, luck, but, most of all, endurance. —James Baldwin 4 C O N T E N T S Crust 10 Christopher Heffernan Jeopardy 11 Chella Courington Roman Candles 12 Flower 12 Women 13 Thom Young A Curl of Severed Hair 14 Before She Went to Sleep 16 North Martel Avenue 18 Platonic Fantasy Roused to Extraordinary Limits 20 Jose Oseguera My True Love is a Lesbian Firefighter Not Only 21 Thomas Badyna FOOTPRINTS -

THE POST-FREUDIAN CASEBOOK NEURONOVEL Krysthol Kauffman Northern Michigan University

Northern Michigan University NMU Commons All NMU Master's Theses Student Works 2010 THE POST-FREUDIAN CASEBOOK NEURONOVEL Krysthol Kauffman Northern Michigan University Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.nmu.edu/theses Recommended Citation Kauffman, Krysthol, "THE POST-FREUDIAN CASEBOOK NEURONOVEL" (2010). All NMU Master's Theses. 425. https://commons.nmu.edu/theses/425 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at NMU Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in All NMU Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of NMU Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected],[email protected]. THE POST-FREUDIAN CASEBOOK NEURONOVEL By Krysthol Kauffman THESIS Submitted to Northern Michigan University In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of MASTER OF ARTS IN ENGLISH Graduate Studies Office 2010 SIGNATURE APPROVAL FORM This thesis by Krysthol Kauffman is recommended for approval by the student‘s thesis committee in the Department of English and by the Dean of Graduate Studies. Committee Chair: Stephen Burn Date: First Reader: Stephen Burn Date: Second Reader: Peter Goodrich Date: Department Head: Ray Ventre Date: Dean of Graduate Studies: Dr. Cynthia Prosen Date: OLSON LIBRARY NORTHERN MICHIGAN UNIVERSITY THESIS DATA FORM In order to catalog your thesis properly and enter a record in the OCLC international bibliographic data base, Olson Library must have the following requested information to distinguish you from others with the same or similar names and to provide appropriate subject access for other researchers. NAME: Kauffman, Krysthol DATE OF BIRTH: July 16, 1986 ABSTRACT THE POST-FREUDIAN CASEBOOK NEURONOVEL By Krysthol Kauffman This thesis focuses on postmodern American fiction, specifically defining a sub- genre of postmodernism that has been developing since at least the 1990s: the Post- Freudian Casebook Neuronovel. -

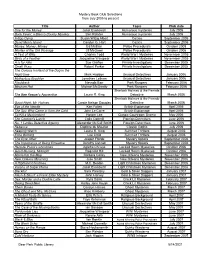

Book Club Back List

Mystery Book Club Selections from July 2005 to present Title Author Topic Club date One for the Money Janet Evanovich Humorous mysteries July 2005 Buck Fever: a Blanco County Mystery Ben Rehder Humorous mysteries July 2005 Indigo Dying Susan Wittig Albert Cozies September 2005 Dead Man's Island Carolyn G. Hart Cozies September 2005 Money, Money, Money Ed McBain Police Procedurals October 2005 Murder at the Old Vicarage Jill McGown Police Procedurals October 2005 A Test of Wills Charles Todd World War I Mysteries Novermber 2005 Birds of a Feather Jacqueline Winspear World War I Mysteries Novermber 2005 A is for Alibi Sue Grafton Private Investigators December 2005 Small Vices Robert Parker Private Investigators December 2005 The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-time Mark Haddon Unusual Detectives January 2006 Motherless Brooklyn Jonathan Lethem Unusual Detectives January 2006 Flashback Nevada Barr Park Rangers February 2006 Mexican Hat Michael McGarrity Park Rangers February 2006 Sherlock Holmes & the Female The Bee Keeper's Apprentice Laurie R. King Detective March 2006 Sherlock Holmes & the Female Good Night, Mr. Holmes Carole Nelson Douglas Detective March 2006 Eye of the Needle Ken Follett British Espionage April 2006 The Spy Who Came in from the Cold John Le Carre British Espionage April 2006 To Kill a Mockingbird Harper Lee Classic Courtroom Drama May 2006 The Coroner's Lunch Colin Cotterill Foreign Detectives June 2006 No. 1 Ladies Detective Agency Alexander McCall Smith Foreign Detectives June 2006 Rebecca Daphne du Maurier