Download Booklet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

English Catholic Music from 1400-1600

King Solomon’s Singers present: Cathedrals and Attic Rooms: English Catholic Music From 1400-1600. Saturday, September 22, 8PM St. Clement Church, Chicago CATHEDRALS AND ATTIC ROOMS: ENGLISH CATHOLIC MUSIC FROM 1400-1600 Nesciens mater John Trouluffe (d. ca. 1473) Quam pulchra es John Dunstable (ca. 1390-1453) Anna mater matris Christi John Plummer (ca. 1410-1483) Magnificat super “O bone Jesu” Robert Fayrfax (1464-1521) Gaude flore virginali William Horwud (1430-1484) Lamentations I Thomas Tallis (1505-1585) Ne irascaris Domine / Civitas sancti tui William Byrd (1540-1623) NOTES ON THE PROGRAM In 1534, the Parliament of England passed the Act of Supremacy, making King Henry VIII head of the Church of England and officially separating English religious practice from Rome and Papal authority. Among the innumerable historical consequences of this event was a significant change in the composition and performance of sacred choral music in England. Until this point, effectively all sacred music in England had been composed for the Roman liturgy or for devotions within the Catholic faith. A strong line of influential composers over the course of over two centuries had developed a clearly definable English Catholic style, most readily identifiable in the works of the Eton Choirbook era. This style of composition is typified by relatively simple underlying harmonic structure decorated with long, ornately melismatic lines—a musical architecture often compared with the Perpendicular Gothic style of English cathedral architecture. This feature of pre-Reformation English sacred music, and the fact that the texts were in Latin, made it an obvious target for the Reformation impulses toward simplicity and the individual’s direct access to God. -

Gabriel Jackson

Gabriel Jackson Sacred choral WorkS choir of St Mary’s cathedral, edinburgh Matthew owens Gabriel Jackson choir of St Mary’s cathedral, edinburgh Sacred choral WorkS Matthew owens Edinburgh Mass 5 O Sacrum Convivium [6:35] 1 Kyrie [2:55] 6 Creator of the Stars of Night [4:16] Katy Thomson treble 2 Gloria [4:56] Katy Thomson treble 7 Ane Sang of the Birth of Christ [4:13] Katy Thomson treble 3 Sanctus & Benedictus [2:20] Lewis Main & Katy Thomson trebles (Sanctus) 8 A Prayer of King Henry VI [2:54] Robert Colquhoun & Andrew Stones altos (Sanctus) 9 Preces [1:11] Simon Rendell alto (Benedictus) The Revd Canon Peter Allen precentor 4 Agnus Dei [4:24] 10 Psalm 112: Laudate Pueri [9:49] 11 Magnificat (Truro Service) [4:16] Oliver Boyd treble 12 Nunc Dimittis (Truro Service) [2:16] Ben Carter bass 13 Responses [5:32] The Revd Canon Peter Allen precentor 14 Salve Regina [5:41] Katy Thomson treble 15 Dismissal [0:28] The Revd Canon Peter Allen precentor 16 St Asaph Toccata [8:34] Total playing time [70:22] Recorded in the presence Producer: Paul Baxter All first recordings Michael Bonaventure organ (tracks 10 & 16) of the composer on 23-24 Engineers: David Strudwick, (except O Sacrum Convivium) February and 1-2 March 2004 Andrew Malkin Susan Hamilton soprano (track 10) (choir), 21 December 2004 (St Assistant Engineers: Edward Cover image: Peter Newman, The Choir of St Mary’s Episcopal Cathedral, Asaph Toccata) and 4 January Bremner, Benjamin Mills Vapour Trails (oil on canvas) 2005 (Laudate Pueri) in St 24-Bit digital editing: Session Photography: -

Musica Britannica

T69 (2021) MUSICA BRITANNICA A NATIONAL COLLECTION OF MUSIC Vauxhall Pleasure Gardens c.1750 Stainer & Bell Ltd, Victoria House, 23 Gruneisen Road, London N3 ILS England Telephone : +44 (0) 20 8343 3303 email: [email protected] www.stainer.co.uk MUSICA BRITANNICA A NATIONAL COLLECTION OF MUSIC Musica Britannica, founded in 1951 as a national record of the British contribution to music, is today recognised as one of the world’s outstanding library collections, with an unrivalled range and authority making it an indispensable resource both for performers and scholars. This catalogue provides a full listing of volumes with a brief description of contents. Full lists of contents can be obtained by quoting the CON or ASK sheet number given. Where performing material is shown as available for rental full details are given in our Rental Catalogue (T66) which may be obtained by contacting our Hire Library Manager. This catalogue is also available online at www.stainer.co.uk. Many of the Chamber Music volumes have performing parts available separately and you will find these listed in the section at the end of this catalogue. This section also lists other offprints and popular performing editions available for sale. If you do not see what you require listed in this section we can also offer authorised photocopies of any individual items published in the series through our ‘Made- to-Order’ service. Our Archive Department will be pleased to help with enquiries and requests. In addition, choirs now have the opportunity to purchase individual choral titles from selected volumes of the series as Adobe Acrobat PDF files via the Stainer & Bell website. -

Alban Notes #52 – Spring 2021

ALBAN NOTES St Albans Cathedral Ex-Choristers Association THE CATHEDRAL AND ABBEY CHURCH OF ST. ALBAN Affiliated to the Federation of Cathedral Old Choristers Associations Issue 52 Spring 2021 Message from the Chairman The last year has been one I don’t think any of us will forget in a hurry, a very strange and challenging 12 months which no-one could have predicted. Covid-19 has had a bigger impact on all our lives than we ever could have imagined, but at last the signs of returning to a new normal are in sight. We are all likely to have either been directly or indirectly affected by the virus and perhaps have been poorly as a result or known people who have been. I hope you are all in good or improving health now and have taken or intend to take advantage of the vaccination programme. As restrictions start to be relaxed over the coming weeks it will be interesting to see how the familiar daily statistics alter, Image © Jellings Paul particularly once we are permitted to travel abroad, and The Very Revd Dr Jeffrey John international borders are relaxed. Time to remain cautious and Patron of the ECA remember the basics of ‘hands, face, space’ as this pandemic is far from over but hopefully becoming more controlled. To our younger members, those who have had important GCSE or A level exams this year or last, and to those at University, I congratulate you on coping with the ever-changing rules and uncertainty which cannot have been easy. You’ve got this far and life will become easier as we learn more about this virus – ‘stay positive and test negative’!! Like much of the UK population, our ECA committee has become familiar with Zoom and have held a couple of successful meetings online. -

Sacred Music and Female Exemplarity in Late Medieval Britain

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles The Iconography of Queenship: Sacred Music and Female Exemplarity in Late Medieval Britain A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Musicology by Gillian Lucinda Gower 2016 © Copyright by Gillian Lucinda Gower 2016 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION The Iconography of Queenship: Sacred Music and Female Exemplarity in Late Medieval Britain by Gillian Lucinda Gower Doctor of Philosophy in Musicology University of California, Los Angeles, 2016 Professor Elizabeth Randell Upton, Chair This dissertation investigates the relational, representative, and most importantly, constitutive functions of sacred music composed on behalf of and at the behest of British queen- consorts during the later Middle Ages. I argue that the sequences, conductus, and motets discussed herein were composed with the express purpose of constituting and reifying normative gender roles for medieval queen-consorts. Although not every paraliturgical work in the English ii repertory may be classified as such, I argue that those works that feature female exemplars— model women who exemplified the traits, behaviors, and beliefs desired by the medieval Christian hegemony—should be reassessed in light of their historical and cultural moments. These liminal works, neither liturgical nor secular in tone, operate similarly to visual icons in order to create vivid images of exemplary women saints or Biblical figures to which queen- consorts were both implicitly as well as explicitly compared. The Iconography of Queenship is organized into four chapters, each of which examines an occasional musical work and seeks to situate it within its own unique historical moment. In addition, each chapter poses a specific historiographical problem and seeks to answer it through an analysis of the occasional work. -

572840 Bk Eton EU

Music from THE ETON CHOIRBOOK LAMBE • STRATFORD • DAVY BROWNE • KELLYK • WYLKYNSON TONUS PEREGRINUS Music from the Eton Choirbook Out of the 25 composers The original index lists more represented in the Eton than 60 antiphons – all votive The Eton Choirbook – a giant the Roses’, and the religious reforms and counter-reforms Choirbook, several had strong antiphons designed for daily manuscript from Eton College of Henry VIII and his children. That turbulence devastated links with Eton College itself: extraliturgical use and fulfilling Chapel – is one of the greatest many libraries (including the Chapel Royal library) and Walter Lambe and, quite Mary’s prophecy that “From surviving glories of pre- makes the surviving 126 of the original 224 leaves in Eton possibly, John Browne were henceforth all generations shall Reformation England. There is a College Manuscript 178 all the more precious, for it is just there in the late 1460s as boys. call me blessed”; one of the proverb contemporary with the one of a few representatives of several generations of John Browne, composer of the best known – and justifiably so Eton Choirbook which might English music in a period of rapid and impressive astounding six-part setting of – is Walter Lambe’s setting of have been directly inspired by development. Eton’s chapel library itself had survived a Stabat mater dolorosa 5 may have gone on to New Nesciens mater 1 in which the composer weaves some the spectacular sounds locked forced removal in 1465 to Edward IV’s St George’s College, Oxford, while Richard Davy was at Magdalen of the loveliest polyphony around the plainchant tenor up in its colourful pages: “Galli cantant, Italiae capriant, Chapel – a stone’s throw away in Windsor – during a College, Oxford in the 1490s. -

Diamm Facsimiles 6

DIAMM FACSIMILES 6 DI MM DIGITAL IMAGE ACHIVE OF MEDIEVAL MUSIC DIAMM COMMITTEE MICHAEL BUDEN (Faculty Board Chair) JULIA CAIG-McFEELY (Diamm Administrator) MATIN HOLMES (Alfred Brendel Music Librarian, Bodleian Library) EMMA JONES (Finance Director) NICOLAS BELL HELEN DEEMING CHISTIAN LEITMEIR OWEN EES THOMAS SCHMIDT diamm facsimile series general editor JULIA CAIG-McFEELY volume editors ICHAD WISTEICH JOSHUA IFKIN The ANNE BOLEYN MUSIC BOOK (Royal College of Music MS 1070) Facsimile with introduction BY THOMAS SCHMIDT and DAVID SKINNER with KATJA AIAKSINEN-MONIER DI MM facsimiles © COPYIGHT 2017 UNIVERSITY OF OXFORD PUBLISHED BY DIAMM PUBLICATIONS FACULTY OF MUSIC, ST ALDATES, OXFORD OX1 1DB ISSN 2043-8273 ISBN 978-1-907647-06-2 SERIES ISBN 978-1-907647-01-7 All rights reserved. This work is fully protected by The UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. No part of the work may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise without the prior permission of DIAMM Publications. Thomas Schmidt, David Skinner and Katja Airaksinen-Monier assert the right to be identified as the authors of the introductory text. Rights to all images are the property of the Royal College of Music, London. Images of MS 1070 are reproduced by kind permission of the Royal College of Music. Digital imaging by DIAMM, University of Oxford Image preparation, typesetting, image preparation and page make-up by Julia Craig-McFeely Typeset in Bembo Supported by The Cayzer Trust Company Limited The Hon. Mrs Gilmour Printed and bound in Great Britain by Short Run Press Exeter CONTENTS Preface ii INTODUCTION 1. -

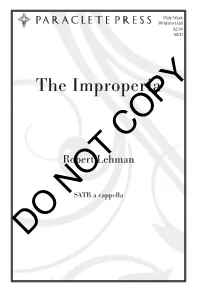

The Improperia I Did Raise Thee on High with Great Power

10 Holy Week paraclete press PPM01916M U $2.90 # # œ M/D & # ## œ œ œ œ œ œ ˙ œ œ œ œ œ ˙. œ œ œ œ œ œ œ ˙ œ œ œ œ ˙. œ w where- in have I wear- ied thee? Test--- i fy a gainst me. œ œ œ ˙ œ œ œ œ ˙ U ? # # œ œ œ œœ œ œ œ ˙ œ œ œœ œ œ ˙ œ œ ww # ## œ Cantor #### & # œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ ˙ The Improperia I did raise thee on high with great power: #### & # œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ ˙ and thou hast hang-- ed me up on the gib- bet of the Cross. Full Choir p COPY # # œ # ## ˙ ˙ ˙ ˙˙ œœ œ œ œ ˙. œ œ œ . & ˙ ˙ ˙ œ œ œ œ œ œ ˙. œ O my peo- ple, what have I done un- to thee? or Robert Lehman œ ˙ ˙ œ œ ˙ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ ˙. œ ? # # ˙ ˙ œ œ ˙ œ œ œ # ## œ œ œ ˙. œ NOTSATB a cappella # # œ U & # ## œ œ œ œ œ œ ˙ œ œ œ œ œ ˙. œ œ œ œ œ œ œ ˙ œ œ œ œ ˙. œ w where- in have I wear- ied thee? Test--- i fy a gainst me. œ œ œ ˙ œ œ œ œ ˙ U ? # # œ œ œ œœ œ œ œ ˙ œ œ œœ œ œ ˙ œ œ ww DO # ## œ PPM01916M 9 Cantor #### & # œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ ˙ I did smite the kings of the Can-- aan ites for thy sake: # ## & # # œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ andœ thou hast smit- ten my head with a reed. -

16Th Century

16th century notes towards the end of the piece are deliberate, and won’t seem so bad if you play them well? In bars 115 and 117 Cherici reproduces the notes as Mudarra had them, but I EDITIONS wonder if there is a case for changing them to match the rest of the sequence from bars 111 to 122, if only in a footnote. Anthology of Spanish Renaissance Music In three of the Fantasias by Mudarra the player is required for Guitar: to use the “dedillo” technique – using the index finger to Works by Milán, Narváez, Mudarra, Valderrábano, Pisador, play up and down like a plectrum. Of the nine pieces from Fuenllana, Daça, Ortiz Enriquez Valderrábano’s Silva de Sirenas (1547), three are Transcribed by Paolo Cherici marked “Primero grado”, i.e. easiest to play. Diego Pisador is Bologna: Ut Orpheus, 2017 CH273 less well known than the other vihuelists, perhaps because accid his Libro de musica de vihuela (1552) contains pages and his well-chosen anthology comprises solo music pages of intabulations of sacred music by Josquin and for the vihuela transcribed into staff notation others. However, there are some small-scale attractive for the modern guitar, and music for the viola da pieces of which Cherici picks five including a simple setting T of La Gamba called Pavana muy llana para tañer. The eight gamba with SATB grounds arranged for two guitars. For the vihuela pieces the guitar must have the third string tuned pieces from Miguel de Fuenllana’s Orphenica Lyra (1554) a semitone lower to bring it into line with vihuela tuning. -

The Magazine of the Prayer Book Society

ANGLICAN WAY The magazine of the Prayer Book Society Volume 40 Number 2 Summer 2017 IN THIS ISSUE Reflections from 2 the Editor’s Desk From the President of 4 the Prayer Book Society The PBS 2017 6 Conference ‘Prevent us Good Lord’: 7 Dwelling, Walking and Serving in the Book of Common Prayer Book Review: The 12 Benedict Option For Every Syllable a 14 Note: Cranmer and musical upheaval in the English Reformation Plainsong Psalms for 16 the Parish: Making a case for congregational psalmody The Liturgy of the 19 Episcopal Church: A Sermon from 1860 23 For Our Country Reflections FROM THE Editor’s Desk Roberta Bayer, Associate Professor, Patrick Henry College, Purcellville, Virginia We need your he Prayer Book Society of England has gra- on Cranmer and the musical upheaval during the gifts in order to ciously allowed us to reprint a talk given English Reformation. He points out that the theology by the Most Rev. and Right Hon. Lord Wil- of the Reformation had a profound effect upon the carry out your Tliams of Oystermouth, former Archbishop of Can- way music was conceived. Mr. Dettra is much lauded mandate to terbury. Lord Williams spoke to the English Prayer for his musical performances both as an organist and defend the Book Society, and once again showed himself to be a choir director, it is an honor and a pleasure to have a contemporary theologian who is willing to praise his article in the magazine. His concert schedule can 1928 Book of Cranmer’s liturgy for its spirituality and its theol- be found online at https://www.scottdettra.com/ Common Prayer. -

Download Booklet

The Sun Most Radiant Music from the Eton Choirbook Volume 4 John Browne (fl. c.1490) 1 Salve regina I a 5 (SATBarB) 15.01 2 Salve regina II a 5 (TTTBarB)* 18.47 William Horwood (c.1430–1484) 3 Gaude flore virginali a 5 (SATTB)* 14.56 William, Monk of Stratford (fl. late 15th – early 16th century) 4 Magnificat a 4 (TTBarB) 19.54 68.42 *world premiere recordings The Choir of Christ Church Cathedral, Oxford Stephen Darlington Director of Music 2 Introduction It is not a surprise that this fourth volume of Eton Choirbook compositions should be so appealing to the Choir of Christ Church, Oxford. After all, we fulfil much the same function as the Eton College Chapel Choir did at the beginning of the 16th century, singing the daily offices with huge commitment and skill. A superficial glance at the structure and musical language of these four works might lead one to suppose that they are all written in a generic style, but each composer has a striking and distinctive voice, ranging from the consummate technical command of John Browne to the rhythmical ingenuity of William Horwood and the energetic imitative vocal interplay of William Stratford. The challenge for us is to revive not only the text but also the spirit of this music which is so glorious in its variety and complexity. Ꭿ Stephen Darlington, 2016 The Sun Most Radiant Of the 25 composers represented in the Eton Choirbook, one name stands out above the others: that of John Browne. He is widely acknowledged to be the finest composer of the collection, and his monumental eight-part antiphon O Maria salvatoris mater (recorded on Choirs of Angels, the second release in this series), has pride of place as the opening piece in the Choirbook. -

Festal Evensong

6 FESTAL EVENSONG for the Feast of the Blessed Virgin Mary August 15 2020 Preparing for Worship Today the Church celebrates the Blessed Virgin Mary, on the date which since the earliest Christian centuries has been kept in her honour. We give thanks for her response to God’s call and her trust in God’s promises, and we allow that faithfulness to point us to her Son Jesus. Much of the music in this service comes from recordings made by the Cathedral Choir under the direction of Dr Stephen Darlington, of material from the Eton Choirbook of the early sixteenth century. This music is often long and complex, but rewards concentrated listening. It is music written to the glory of God; to display the skill of the composers, clerks and choristers of the late fifteenth century; and to lift the hearts and minds of those who listen, that we may experience through the glory of richly complex music something of the glory of God and the song of the angels. It is supplemented by other recordings, by the Cathedral Choir and Cathedral Singers, both from our archives and recorded more recently. The Officiant is the Revd Canon Sarah Foot, Regius Professor of Ecclesiastical History. Entering into worship through audio broadcast is more familiar to some of us than to others. If this is new to you, try to actively share in the service, not just have it on in the background; and join in the words in bold. Find a comfortable position that helps you to pray, and to receive the love of God in your heart.