Populism, Energy Walls, and Executive Domination

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

P-00418 Page 1 CBC

CIMFP Exhibit P-00418 Page 1 CBC Canadian taxpayers will ultimately bear Muskrat Falls burden, predicts Ron Penney Longtime critic of hydro project says NL taxpayer cannot afford the billions in debt Terry Roberts · CBC News · Posted: Sep 13, 2018 8:20 PM NT | Last Updated: September 16 Ron Penney is a former senior public servant in Newfoundland and Labrador and outspoken critic of the controversial Muskrat Falls project. (Eddy Kennedy/CBC) Ron Penney says Canadians from across the country should be deeply worried about Muskrat Falls, because he's certain they will shoulder the burden of the billions being spent to construct the controversial hydroelectric project in Labrador. "One hundred per cent," Penney says when asked if Ottawa will have to bail out the province for taking a gamble that has "gone very, very wrong." CIMFP Exhibit P-00418 Page 2 Lonely critics Penney is a lawyer and former senior public servant with the province and the City of St. John's. He's also among the founding members of the Muskrat Falls Concerned Citizens Coalition. The spillway at Muskrat Falls. (Eddy Kennedy/CBC) Penney and David Vardy, another former senior public servant, were early and vocal critics of Muskrat Falls at a time when public opinion was solidly behind it and former premier Danny Williams, a hard-charging politician who wielded a lot of influence, was its biggest booster. Opposing the project in those days invited ridicule and dismissal, making it difficult for people to speak out, said Penney, in a province where "dissent is frowned upon" and so many people are connected to government in some way. -

Former Provincial Government Officials 2003-2015

Commission of Inquiry Respecting the Muskrat Falls Project STANDING APPLICATIONS FOR FORMER GOVERNMENT OFFICIALS 2003 - 2015 AS REPRESENTED BY DANNY WILLIAMS, Q.C. THOMAS MARSHALL, Q.C., PAUL DAVIS, SHAWN SKINNER, JEROME KENNEDY, Q.C. AND DERRICK DALLEY FOR THE MUSKRAT FALLS INQUIRY DECISION APRIL 6, 2018 LEBLANC, J.: INTRODUCTION [1] Danny Williams, Q.C., Thomas Marshall, Q.C., Paul Davis, Shawn Skinner, Jerome Kennedy, Q.C. and Derrick Dalley have applied as a group, referred to as Former Government Officials 2003 - 2015. All are members of past Progressive Conservative administrations in place from 2003 up to December 2015. It was during this period of time that the Muskrat Falls Project was initiated, sanctioned and construction commenced. Mr. Williams, Mr. Marshall and Mr. Davis were the Premier of the Province at various times throughout this period while Mr. Skinner, Mr. Kennedy and Mr. Dalley, along with Mr. Marshall, were the Minister of Natural Resources at various times. In those capacities all were significantly involved with this Project. The applicants now apply as a group for full standing at the Inquiry hearings on the basis that they have a common or similar interest in the Inquiry's investigative mandate. Page2 [2] The applicants also seek a funding recommendation for one counsel to act on behalf of the group in order to represent their interests at the Inquiry hearings. [3] There is also a request by the applicants that they individually be entitled to retain their own separate legal counsel, without any funding request, to represent the interests of each individual as they may arise during the course of the Inquiry. -

In Collaboration with CSTM/SCTM

FEREN CON CE PROGRAM laboration with CSTM/ In col SCTM IC TM 2011 WE’RE PROUD TO WELCOME THE 41ST WORLD CONFERENCE OF ICTM to Memorial University and to St. John’s, Newfoundland and Labrador. This is a unique corner of Canada, the only part that was once an independent country and then the newest Canadian province (since 1949) but one of the oldest meeting points for natives and new- comers in North America. With four Aboriginal cultures (Inuit, Innu, Mi’kmaq, Métis); deep French, English, Irish, and Scottish roots; and a rapidly diversifying contemporary society, our citizens have shared a dramatic history, including a tsunami, an occupation during WWII, a fragile dependence on the sea including a cod moratorium in recent decades, a key role in the events of 9/11, and more recently, an oil boom. Its nickname – The Rock – tells a lot about its spectacular geography but also about its resilient culture. Traditional music and dance are key ingredients in life here, as we hope you will learn in the week ahead. Our meetings will take place at Memorial University, shown in the foreground of the photo below, and in the Arts & Culture Centre just to the west of the campus. To celebrate the conference themes in music itself, and to bring the public in contact with the remarkable range of scholars and musicians in our midst, we have organized the SOUNDshift Festival to run concurrently with the World Conference of ICTM. Five concerts, open to delegates and the general public, workshops by ICTM members and musicians featured on the concerts, and films are available as part of this festival. -

Nalcor Energy Energizing Atlantic Canada GE Helps Nalcor Energy Build an Energy Corridor Moving More Power from Labrador to Newfoundland and Nova Scotia

GE Grid Solutions Nalcor Energy Energizing Atlantic Canada GE Helps Nalcor Energy Build An Energy Corridor Moving More Power From Labrador to Newfoundland and Nova Scotia . Imagination at work The Challenge Nalcor Energy will build a High Voltage Direct Current (HVDC) transmission line engineered to both preserve the fragile ecosystem and withstand the harsh weather experienced in Canada to replace thermal power generation in the provinces of Newfoundland and Nova Scotia. The Solution Move More Power, More Efficiently The 350 kV Line Commutated Converter (LCC) HVDC transmission link will provide 900 MW of bulk hydro power over 1100 km of forests and frozen grounds, 34 km of which will be The HVDC Link From Muskrat Falls to Soldiers Pond underwater cables crossing the Strait of Belle Isle, avoiding frozen sea, high current, blizzards and icebergs. HVDC solutions can: ' transmit up to three times more power in the same transmission right of way as Alternating Current (AC) ' precisely control power transmission exchanges ' reduce overall transmission losses ' control the network efficiency GE’s full turnkey project scope includes converter stations at Muskrat Falls (Labrador) and at Soldiers Pond (Newfoundland) with the following main components: ' valves ' converter transformers ' control system Lower Churchill River, Labrador, North East of Canada ' 2 transition compounds at the strait to join maritime lines to overhead ones TRANSITION TRANSITION WATER DAM CONVERTER COMPOUND COMPOUND CONVERTER ±350 kV, 900 MW HVDC Link LABRADOR STRAIT OF BELLE ISLE NEWFOUNDLAND Nalcor Energy's ±350 kV, 900 MW HVDC Power Line at Muskrat Falls, Labrador, Canada 2 GEGridSolutions.com The Benefits Canadian transmission network operator Nalcor Energy will carry electricity from central Labrador to the 475,000 customers, residents and industries, on the Newfoundland island. -

Lieu/Rot/Cid-Land Labrador

CIMFP Exhibit P-04096 Page 1 (-IZ v-td Mo .23 //8 vi•c, ez5u kfriai lieu/rot/Cid-Land Government of Newfoundland and Labrador Department of Natural Resources Labrador Office of the Minister MAY 162018 Mr. Brendan Paddick, Chair Board of Directors Nalcor Energy 500 Columbus Drive P.O. Box 12800 St. John's, NL Al B 0C9 Dear Mr. Paddick: RE: Allegations against Nalcor Energy and its Employees In correspondence to the Honourable Dwight Ball, Premier of Newfoundland and Labrador, as attached and as well as in direct meetings with this Department, concerned citizens have made serious allegations concerning Nalcor Energy ("Nalcor) including its operations, activities, and the conduct of company officials and contractors. In view of these complaints and on the advice we have received from the Department of Justice and Public Safety, I am writing to request that the Internal Auditors at Nalcor, on behalf of the Board, conduct an investigation into the allegations and provide this office with those findings. The alleged incidents include harassment, safety concerns, misappropriation of funds, theft, overcharging and personal trips paid by Nalcor. Nalcor management personnel are also alleged to have been involved in some of these activities. I request that a report be provided to me within 60 days. This report should detail the investigation, findings, and actions Nalcor has taken to address its findings, including whether the actions are employment-related or mandate referral to the Royal Newfoundland Constabulary or the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, as appropriate. I also recommend that Nalcor disclose all relevant information relating to costs of the Muskrat Falls Project to the Commission of Inquiry Respecting the Muskrat Falls Project Order as led by Commissioner Justice Richard D. -

2016 Business and Financial REPORT 2016 Business and Financial REPORT

2016 Business and Financial REPORT 2016 Business and Financial REPORT TABLE OF CONTENTS 02 2016 ACHIEVEMENTS 04 CORPORATE PROFILE 07 MESSAGE FROM THE CHAIR 08 MESSAGE FROM THE CEO 10 SAFETY 12 ENVIRONMENT BUSINESS EXCELLENCE 14 MUSKRAT FALLS PROJECT 18 HYDRO 22 OIL AND GAS 24 BULL ARM 25 ENERGY MARKETING 26 CHURCHILL FALLS 28 PEOPLE 29 COMMUNITY 30 OPERATING STATISTICS 31 FINANCIAL STATISTICS 32 EXECUTIVE, DIRECTORS AND OFFICERS 34 CORPORATE GOVERNANCE APPENDIX 1 MANAGEMENT’S DISCUSSION & ANALYSIS APPENDIX 2 CONSOLIDATED FINANCIAL STATEMENTS – DECEMBER 31, 2016 Nalcor Energy is a proud, diverse energy company focused on the sustainable development of Newfoundland and Labrador’s energy resources. 2016 ACHIEVEMENTS FINANCIAL HIGHLIGHTS DEBT-TO-CAPITAL TOTAL ASSETS ($) 2016 60.7% 2016 14.1B 2015 64.5% 2015 12.3B 2014 69.2% 2014 10.6B 3.2B 136.3M 810.5M 824.1M 2.8B 798M 115.6M 2.0B 45.7M 2014 2015 2016 2014 2015 2016 2014 2015 2016 CAPITAL EXPENDITURE ($) REVENUE ($) OPERATING PROFIT ($) SAFETY ENVIRONMENT Achieved all corporate safety metrics of environmental targets achieved • All-injury frequency rate • Lost-time injury frequency rate • Lead / lag ratio Hydro’s activities in the takeCHARGE 15% ZERO programs helped its customers 1,976 MWh reduction in lost-time injuries reduce electricity use by recordable injuries maintained in over previous year several areas COMMUNITY Nalcor supported more than 40 organizations throughout Newfoundland and Labrador. 2 Nalcor Energy Business and Financial Report 2016 HYDRO OIL & GAS 25.5 BILLION BARRELS COMPLETED of OIL and 20.6 TRILLION MORE THAN CUBIC FEET of GAS Since 2011, over potential identified in an 145,000 line kilometres independent study covering PROJECTS of NEW 2-D multi-client blocks on offer in the AND data acquired. -

Newfoundland and Labrador Hydro

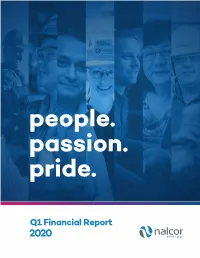

people. passion. pride. Q1 Financial Report 2020 CONTENTS 1 APPENDIX 1 NALCOR ENERGY CONDENSED CONSOLIDATED INTERIM FINANCIAL STATEMENTS March 31, 2020 (Unaudited) NALCOR ENERGY CONSOLIDATED STATEMENT OF FINANCIAL POSITION (Unaudited) March 31 December 31 As at (millions of Canadian dollars) Notes 2020 2019 ASSETS Current assets Cash and cash equivalents 248 174 Restricted cash 1,381 1,460 Trade and other receivables 5 200 240 Inventories 117 134 Other current assets 6 96 33 Total current assets before distribution to shareholder 2,042 2,041 Assets for distribution to shareholder 4 - 1 Total current assets 2,042 2,042 Non-current assets Property, plant and equipment 7 16,695 16,798 Intangible assets 35 36 Investments 340 334 Other long-term assets 8 8 Total assets 19,120 19,218 Regulatory deferrals 8 121 123 Total assets and regulatory deferrals 19,241 19,341 LIABILITIES AND EQUITY Current liabilities Short-term borrowings 9 223 233 Trade and other payables 429 435 Other current liabilities 48 50 Total current liabilities 700 718 Non-current liabilities Long-term debt 9 9,648 9,649 Class B limited partnership units 590 578 Deferred credits 1,812 1,812 Decommissioning liabilities 112 102 Employee future benefits 146 144 Other long-term liabilities 70 70 Total liabilities 13,078 13,073 equity Share capital 123 123 Shareholder contributions 4,609 4,608 Reserves (42) (101) Retained earnings 1,454 1,625 Total equity 6,144 6,255 Total liabilities and equity 19,222 19,328 Regulatory deferrals 8 19 13 Total liabilities, equity and regulatory -

Outlet Winter 2013

Winter 2013 6 Keeping the public safe around dams 10 Churchill Falls prepares 16 President’s Awards for its next generation celebrates five-years of employee recognition 20 Employees join the Red Shoe Crew to support Ronald McDonald House Newfoundland and Labrador Outlet - Summer 2012 1 Plugged In 2 Leadership Message Safety 3 Safety 7 Environment 9 Business Excellence 14 People 20 Community 23 Highlights Environment Please visit us at: Excellence Facebook: facebook.com/nalcorenergy facebook.com/nlhydro Twitter: twitter.com/nalcorenergy twitter.com/nlhydro Business YouTube: youtube.com/nalcorenergy youtube.com/nlhydro Outlet is Nalcor Energy’s corporate magazine, published semi-annually by Corporate Communication & Shareholder Relations. People For more information, to provide feedback or to submit articles or ideas, contact us at 709.737.1446 or [email protected] Front Cover The 2012 President’s Award Winners. Community Nalcor Energy Plugged In – July to December 2012 • In November, a power outage safety contest on Hydro’s Facebook page saw users participate with more than 1,480 tips, “likes” and shares of information on the page. Users shared their own tips and advice on how to prepare for an unplanned power outage. • By the end of November 2012, Nalcor EnergySafety employees submitted more 6,800 safety-related SWOPs in the database. • Nalcor’s Environmental Services department completed a waste audit study in Bay d’Espoir in September. The type and quantity of waste leaving the site was examined. The report will look at opportunities to enhance reduction of non-hazardous waste being sent to the landfill. • In November, takeCHARGEEnvironment gave away 500 block heater timers in Labrador City and Happy Valley-Goose Bay. -

Premier's Task Force on Improving Educational Outcomes

The Premier’s Task Force on Improving Educational isNow the Outcomes Time The Next Chapter in Education in Newfoundland and Labrador THE PREMIER’S TASK FORCE ON IMPROVING EDUCATIONAL OUTCOMES Dr. Alice Collins, Chair Dr. David Philpott Dr. Marian Fushell Dr. Margaret Wakeham Charlotte Strong, B.A., M.Ed. Research Consultant Sheila Tulk-Lane, B.A. Administrative Assistant 2017 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The Premier’s Task Force on Improving Educational Outcomes wishes to acknowledge the support received from each of the government departments, especially those with youth serving mandates. The task force also acknowledges the participation of students, educators and the general public in the information gathering process. On cold winter nights people came to share their experiences and opinions in the belief that it would create change. We remember a mother who drove 45 minutes through freezing rain at night to tell about her experiences over fifteen years advocating on behalf of her son with autism who is graduating this year. “I know this won’t impact him but I hope it might help the next family that comes along.” Special thanks to: Eldred Barnes Paul Chancey Kim Christianson Lloyd Collins Don McDonald Chris Mercer Sharon Pippy Kerry Pope Scott Rideout Anne Marie Rose QC Bonita Ryan Ross Tansley Jim Tuff Sheila Tulk-Lane We extend sincere appreciation to Charlotte Strong. Charlotte’s passion for learning was a constant reminder of the importance of striving to improve educational outcomes for every child in this province. We will each say that having the opportunity to work with her will remain a highlight of our careers. -

Dunderdale When

CIMFP Exhibit P-01613 Page 1 The Telegram SmartEdition- The Telegram (St. John's)- 3 Dec 2011- Muskrat is aboutj ... Page 1 of2 (\j(l_ tc Article rank 3 Dec 2ou The Telegmm (St. John's) BYJAMESMCLEOD THE TELEGRAM thetelegmm.com nuitter: Telegmmjames Muskrat is about just two questions: Dunderdale When Muskrat falls. it comes to Muskrat Falls, Premier Kathy Dunderdale says people should only think about two simple questions. "First of all, do we need the power?" she asked Friday. "And the second question we've got to ask Is: what's the cheapest way?" Dunderdale was echoing Natural Resources Minister Jerome Kennedy, who said Thursday that the whole hydroelectric project bolls down to the same two questions. The government vehemently Insists that yes, the province needs the power, and that Independent assessments will prove that the Churchill River hydroelectric dam Is the cheapest way to generate lt. CIMFP Exhibit P-01613 Page 2 The Telegram SmartEdition- The Telegram (St. John's)- 3 Dec 2011- Muskrat is aboutj ... Page 2 of2 "'We can't buy it from Quebec any cheaper, we can't build It any cheaper, we can't bring It In from Nova Scotia any cheaper. "That Is the cheapest we can get It In Newfoundland and Labrador,,. she said. Members of the Uberal Party- the project's loudest opponents- have disputed the answers to both of those questions. Critics have also raised any number of specific technical objections with the project and how the development deal Is structured. Most recently, project partner Emera said that energy prices In the 14-16 cent per kilowatt/hour range was too high, and they would never go forward with the project at those rates. -

Quebec-Newfoundland and Labrador's Relationship Valérie

Uneasy Neighbours: Quebec-Newfoundland and Labrador's Relationship Valérie Vézina Faculty, Political Science Kwantlen Polytechnic University [email protected] Note: This is a work in progress. Please do not cite without the permission of the author. Newfoundland and Labrador only has one direct territorial contact with another province: Quebec. The harsh and often unwelcoming territory of Labrador has been the centre of the animosity between the two provinces. In the recent Supreme Court ruling regarding Churchill Falls, the Court, in a 7-1 decision, ruled that Quebec had no obligation to renegotiate the contract. Despite the reassuring words of the Newfoundland and Labrador Premier, Dwight Ball, that the two provinces have much more to gain collaborating and that he would do so with Quebec Premier, François Legault, the general comments in both provinces by citizens does not tend towards collaboration and friendship. Why is that so? What are the factors that have contributed in the past to so many tensions between the two neighbours? What contributes today to such feelings among the public despite the willingness of political actors to move on, to develop partnerships? This paper will explore these questions. It will be revealed that 'historical' collective memories as well as cultural products (songs, humour, slogans) have helped perpetuating an uneasy relationship among Quebec and Newfoundland and Labrador. Resentment can be an individual emotion, an anger felt towards a perceived injustice. However, as Stockdale (2013) argues, resentment is certainly individual but can also be collective. She demonstrates that "the reasons for resentment in cases of broader social and political resentments will often be tied to social vulnerability and experiences of injustice." (Stockdale, 2013: 5) Furthermore, "collective resentment is resentment that is felt and expressed by individuals in response to a perceived threat to a collective to which they belong. -

· ,Fl to Raise Fund For

Memorial University of Newfoundland Alumni Association Vol. 22, No. 4, Spring 1997 · ,fl to raise fund for: 45 and research i 40 35 facilit,·............ The federal government has emphasized the importance of tax-sheltered Registered Education Savings Plans (RESPs) in their recent budget: • Annual contribution limits are now doubled to $4,000 • RESP interest may now be transferable to your RRSP, should your child not pursue post-secondary education The Canadian Scholarship Trust Plan is still your best choice: • We're the first and largest RESP in Canada since 1960 • We're administered by a non-profit foundation • We have more than 130,000 subscribers and over $800 million under administration Call 1-800-387-4622 or visit our web page at www.cst.orglntglcst at are ou waitin_ or? LUMINUS E P.!.T..QB ..~.$. ... .Y.!.f.Jf. Vol. 22, No. 4, Spring 1997, Memorial University of Newfoundland Alwnni Association The launch of The Opportunity ON OUR COVER Fund, Memorial ALUMNI HERE AND THERE University's $50- 6 Memorial launches $50 million 16 Working as a flying doctor in Australia million fund- fund-raising campaign raising campmgn, 15 Jamming on the internet was certainly the FEATURES highlight of my 16 The belle of the ball time here with the Karen Leonard 10 Annual Giving Fund 15 Promoting Newfoundland art Campaign Planning Alumnus gives over $400,000 to Office. I think it's the biggest example scholarships of team effort I've ever seen, with so many having a hand in its success. DEPARTMENTS I've had the pleasure of interviewing and talking to many 2 MUN Clips 15 Alumni Here & There students, faculty and staff, and have 4 Research @ MUN 19 Student Perspectives found them all great to work with.