Lafco: the Nerdiest City Commission You’Ve Never Heard Of” “For Ride‐Hailing Drivers, Data Is Power”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mitigating the Spread of COVID-19 in the SF County Jails and Criminal Legal System

Paul M. Miyamoto, San Francisco County Sheriff Garret L. Wong, San Francisco County Superior Court Presiding Judge Chesa Boudin, San Francisco County District Attorney London Breed, San Francisco Mayor San Francisco County Board of Supervisors: Norman Yee, President, District 7 Sandra Lee Fewer, District 1 Catherine Stefani, District 2 Aaron Peskin, District 3 Gordon Mar, District 4 Dean Preston, District 5 Matt Haney, District 6 Rafael Mandelman, District 8 Hillary Ronen, District 9 Shamann Walton, District 10 Ahsha Safaí, District 11 Sent via Email March 19, 2020 RE: Mitigating the Spread of COVID-19 in the SF County Jails and Criminal Legal System Dear San Francisco Elected Officials, The concerns around the COVID-19 pandemic have become graver by the day. As a result of an announcement made earlier this week, six Bay Area counties have begun a “shelter in place.” This follows the federal administration’s declaration of a national emergency earlier this month. We are seeing the numbers of people contracting COVID-19 rise every day, with local governments, community organizations, and residents themselves doing all they can to prepare and ensure they are equipped to endure this pandemic. Unfortunately, we have not done nearly enough to ensure the safety, health, and well being of our community members that are locked in the county jails. As both health and criminal justice experts have noted, carceral settings, including prisons, jails, and detention centers, are known incubators of infectious diseases. Additionally, incarcerated people have an inherently limited ability to fight the spread of infectious disease: they are confined in close quarters and cannot avoid contact with people who may have been exposed, especially when testing is not prioritized or accessible. -

FORM SFEC-161(A): ITEMIZED DISCLOSURE STATEMENT for MASS MAILINGS (S.F

San Francisco Ethics Commission For SFEC use 25 Van Ness Avenue, Suite 220 San Francisco, CA 94102 Phone: (415) 252-3100 Fax: (415) 252-3112 Email: [email protected] Web: www.sfethics.org FORM SFEC-161(a): ITEMIZED DISCLOSURE STATEMENT FOR MASS MAILINGS (S.F. Campaign and Governmental Conduct Code § 1.161(a)) Instructions: Any candidate for City elective office who pays for a mass mailing must file two clearly legible pieces of the mass mailing and this Itemized Disclosure Statement within: 1) five (5) working days after the date of the mailing; or 2) 48 hours of the date of the mailing if the date of the mailing occurs within the final 16 days before the election. The mailing may be filed in paper or electronic format. Electronic proofs are preferred. What is a mass mailing? A mass mailing is over 200 substantially similar pieces of mail, including but not limited to fundraising solicitations and campaign literature that also advocate for or against one or more candidates for City elected office. Which mass mailings are subject to disclosure? Mass mailings that (1) are paid for by a candidate for City elective office from his or her campaign funds, and (2) advocate for or against candidates for City elective office are subject to disclosure. S.F. C&GC Code § 1.161(a)(1). What information must the candidate disclose? The candidate must disclose the itemized costs associated with the mailing, including but not limited to the amounts paid for photography, design, production, printing, distribution and postage. The candidate must show each separate charge or payment for each cost associated with the mass mailing. -

Executive Summary Conditional Use HEARING DATE: SEPTEMBER 13, 2018

Executive Summary Conditional Use HEARING DATE: SEPTEMBER 13, 2018 Date: September 6, 2018 Case No.: 2018-007741CUA Project Address: 3133 Taraval Street Zoning: Residential-Mixed, Low Density District (RM-1) 40-X Height and Bulk District Block/Lot: 2384/027 Project Sponsor: Patrice Fambrini Jaidin Consulting Group 205 13th Street San Francisco, CA, 94103 Staff Contact: Jeff Horn – (415) 575-6925 [email protected] PROJECT DESCRIPTION The proposal is to convert a vacant 1,740 square-foot two-story single-family dwelling to a Community Center for seniors (dba Self-Help for the Elderly). The project also proposes a 1,500 square-foot two-story rear addition, for a total building size of 3,240 gross square feet. An existing garage door will be removed and replaced with double doors providing access to the facility directly from the ground floor. REQUIRED COMMISSION ACTION In order for the Project to proceed, the Commission must grant a Conditional Use Authorization, pursuant to Planning Code Sections 209.2, 303 and 317 to authorize the conversion of a dwelling unit and to establish a Community Facility (A Community Center for seniors). ISSUES AND OTHER CONSIDERATIONS Public Comment & Outreach. The Project Sponsor has submitted letters of support from District 4 Supervisor, Katy Tang, Executive Director of Department on Aging and Adult Services, Shireen McSpadden, San Francisco Assessor, Carmen Chu, 45 signed form letters of support, and a petition of support with 395 Signatures (for brevity, only one copy of the form letter and only the first and last pages of the petition sheets were included as attachment). -

December 7, 2020 by Email San Francisco Board of Supervisors Board of Supervisor, District 1, Sandra Lee Fewer Board of Supervis

& Karl Olson [email protected] December 7, 2020 By Email San Francisco Board of Supervisors [email protected] Board of Supervisor, District 1, Sandra Lee Fewer [email protected] Board of Supervisor, District 2, Catherine Stefani [email protected] Board of Supervisor, District 3, Aaron Peskin [email protected] Board of Supervisor, District 4, Gordon Mar [email protected] Board of Supervisor, District 5, Dean Preston [email protected] Board of Supervisor, District 6 Matt Haney [email protected] Board of Supervisor, District 7, Norman Yee [email protected] Board of Supervisor, District 8 Rafael Mandelman [email protected] Board of Supervisor, District 9, Hillary Ronen [email protected] Board of Supervisor, District 10, Shamann Walton [email protected] Board of Supervisor, District 11, Ahsha Safaí [email protected] 1 Dr. Carlton B. Goodlett Place City Hall, Room 244 San Francisco, Ca. 94102-4689 Re: Legal Notices to Marina Times (Scheduled for Hearing December 8, 2020) Dear Members of the Board of Supervisors: I am writing on behalf of my client the Marina Times (and its editor in chief Susan Dyer Reynolds), which has been singled out from other independent newspapers in the City qualified to receive legal notices under 1994’s Proposition J because it dared to exercise its First Amendment rights and criticize people in public office. It appears that peacefully exercising First Amendment rights, which can get you killed in some countries, may get you punished in San Francisco even by people who call themselves progressive. A little background is in order. -

Personal Information That Is Provided in Communications to the Board Of

FILE NO. 130218 Petitions and Communications received from February 25, 2013, through March 4, 2013, for reference by the President to Committee considering related matters, or to be ordered filed by the Clerk on March 12, 2013. Personal information that is provided in communications to the Board of Supervisors is subject to disclosure under the California Public Records Act and the San Francisco Sunshine Ordinance. Personal information will not be redacted. From Clerk of the Board, reporting the following individuals have submitted a Form 700 Statement: ( 1) Malia Cohen - Supervisor - Annual Katy Tang - Supervisor-Assuming Katy Tang - Legislative Assistant- Leaving Matthias Mormino - Legislative Assistant - Annual Amy Chan - Legislative Assistant - Annual From National Shooting Sports Foundation, Inc., regarding ammunition proposals. File No. 130040. Copy: Neighborhood Services & Safety Committee Clerk. (2) From concerned citizens, regarding the renaming of SFO. File No. 130037. 4 Letters. Copy: Each Supervisor. (3) From the Mayor, submitting Notice of Appointment for the Historic Preservation Commission. Copy: Each Supervisor, Rules Committee Clerk. (4) Jonathan Pearlman Ellen Johnck From Supervisor Mark Farrell, submitting a memo regarding the Budget & Finance Committee Schedule. (5) From the Mayor, submitting issuance of the Oath of Office to the District 4 seat of the Board of Supervisors. Copy: Each Supervisor. (6) Katy Tang From concerned citizens, regarding opposition to the Pagoda Palace. File No. 130019. 3 Letters. Copy: Land Use & Economic Development Committee Clerk. (7) From the Youth Commission, regarding Four Youth Commission actions. File No. 120669. Copy: Land Use & Economic Development Committee Clerk. (8) From Supervisor Chiu, regarding the updated Government Audit & Oversight Committee Assignments. -

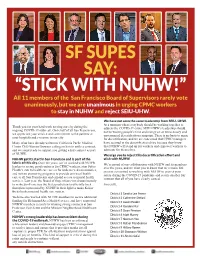

SF BOS Letter to CPMC Members

SF SUPES SAY: “STICK WITH NUHW!” All 11 members of the San Francisco Board of Supervisors rarely vote unanimously, but we are unanimous in urging CPMC workers to stay in NUHW and reject SEIU-UHW. We have not seen the same leadership from SEIU–UHW. At a moment when everybody should be working together to Thank you for your hard work serving our city during the address the COVID-19 crisis, SEIU-UHW’s leadership should ongoing COVID-19 outbreak. On behalf of all San Franciscans, not be wasting people’s time and energy on an unnecessary and we appreciate your service and commitment to the patients at unwarranted decertification campaign. There is no basis to argue your hospitals and everyone in our city. for decertification, and we are concerned that CPMC managers Many of us have already written to California Pacfic Medical have assisted in the decertification drive because they know Center CEO Warren Browner calling on him to settle a contract, that NUHW will stand up for workers and empower workers to and we stand ready to support you getting a fair contract as part advocate for themselves. of NUHW. We urge you to reject this decertification effort and NUHW got its start in San Francisco and is part of the stick with NUHW. fabric of this city. Over the years, we’ve worked with NUHW We’re proud of our collaboration with NUHW and its members leaders to secure good contracts for CPMC workers, stop Sutter over the years, and we want you to know that we remain 100 Health’s cuts to health care access for underserved communities, percent committed to working with NUHW to protect your and initiate pioneering programs to provide universal health safety during the COVID-19 pandemic and secure another fair care to all San Franciscans and expand access to mental health contract that all of you have clearly earned. -

Meeting Minutes

BOARD OF SUPERVISORS CITY AND COUNTY OF SAN FRANCISCO MEETING MINUTES Tuesday, April 2, 2019 - 2:00 PM Legislative Chamber, Room 250 City Hall, 1 Dr. Carlton B. Goodlett Place San Francisco, CA 94102-4689 Regular Meeting NORMAN YEE, PRESIDENT VALLIE BROWN, SANDRA LEE FEWER, MATT HANEY, RAFAEL MANDELMAN, GORDON MAR, AARON PESKIN, HILLARY RONEN, AHSHA SAFAI, CATHERINE STEFANI, SHAMANN WALTON Angela Calvillo, Clerk of the Board BOARD COMMITTEES Committee Membership Meeting Days Budget and Finance Committee Wednesday Supervisors Fewer, Stefani, Mandelman, Ronen, Yee 1:00 PM Budget and Finance Federal Select Committee 2nd and 4th Thursday Supervisors Fewer 1:15 PM Budget and Finance Sub-Committee Wednesday Supervisors Fewer, Stefani, Mandelman 10:00 AM Government Audit and Oversight Committee 1st and 3rd Thursday Supervisors Mar, Brown, Peskin 10:00 AM Land Use and Transportation Committee Monday Supervisors Peskin, Safai, Haney 1:30 PM Public Safety and Neighborhood Services Committee 2nd and 4th Thursday Supervisors Mandelman, Stefani, Walton 10:00 AM Rules Committee Monday Supervisors Ronen, Walton, Mar 10:00 AM First-named Supervisor is Chair, Second-named Supervisor is Vice-Chair of the Committee. Volume 114 Number 10 Board of Supervisors Meeting Minutes 4/2/2019 Members Present: Vallie Brown, Sandra Lee Fewer, Matt Haney, Rafael Mandelman, Gordon Mar, Aaron Peskin, Hillary Ronen, Ahsha Safai, Catherine Stefani, Shamann Walton, and Norman Yee The Board of Supervisors of the City and County of San Francisco met in regular session on Tuesday, April 2, 2019, with President Norman Yee presiding. President Yee called the meeting to order at 2:01 p.m. -

Contacting Your Legislators Prepared by the Government Information Center of the San Francisco Public Library - (415) 557-4500

Contacting Your Legislators Prepared by the Government Information Center of the San Francisco Public Library - (415) 557-4500 City of San Francisco Legislators Mayor London Breed Board of Supervisors voice (415) 554-6141 voice (415) 554-5184 fax (415) 554-6160 fax (415) 554-5163 1 Dr. Carlton B. Goodlett Place, Room 200 1 Dr. Carlton B. Goodlett Place, Room 244 San Francisco, CA 94102-4689 San Francisco, CA 94102-4689 [email protected] [email protected] Members of the San Francisco Board of Supervisors Sandra Lee Fewer Catherine Stefani Aaron Peskin District 1 District 2 District 3 voice (415) 554-7410 fax voice (415) 554-7752 fax (415) voice (415) 554-7450 fax (415) 554-7415 554-7843 (415) 554-7454 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Gordon Mar Vallie Brown Matt Haney District 4 District 5 District 6 voice (415) 554-7460 voice (415) 554-7630 voice (415) 554-7970 fax (415) 554-7432 fax (415) 554-7634 fax (415) 554-7974 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Norman Yee * Rafael Mandelman Hillary Ronen District 7 District 8 District 9 voice (415) 554-6516 voice (415) 554-6968 voice (415) 554-5144 fax (415) 554-6546 fax (415) 554-6909 fax (415) 554-6255 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Shamann Walton Ahsha Safaí District 10 District 11 voice (415) 554-7670 voice (415) 554-6975 fax (415) 554-7674 fax (415) 554-6979 [email protected] [email protected] *Board President California State Legislator Members from San Francisco Senate Scott Wiener (D) District 11 voice (916) 651-4011 voice (415) 557-1300 Capitol Office 455 Golden Gate Avenue, Suite State Capitol, Room 4066 14800 Sacramento, CA 95814-4900 San Francisco, CA 94102 [email protected] Assembly David Chiu (D) District 17 Philip Y. -

Meeting Minutes

BOARD OF SUPERVISORS CITY AND COUNTY OF SAN FRANCISCO MEETING MINUTES Tuesday, June 11, 2019 - 2:00 PM Legislative Chamber, Room 250 City Hall, 1 Dr. Carlton B. Goodlett Place San Francisco, CA 94102-4689 Regular Meeting NORMAN YEE, PRESIDENT VALLIE BROWN, SANDRA LEE FEWER, MATT HANEY, RAFAEL MANDELMAN, GORDON MAR, AARON PESKIN, HILLARY RONEN, AHSHA SAFAI, CATHERINE STEFANI, SHAMANN WALTON Angela Calvillo, Clerk of the Board BOARD COMMITTEES Committee Membership Meeting Days Budget and Finance Committee Wednesday Supervisors Fewer, Stefani, Mandelman, Ronen, Yee 1:00 PM Budget and Finance Sub-Committee Wednesday Supervisors Fewer, Stefani, Mandelman 10:00 AM Government Audit and Oversight Committee 1st and 3rd Thursday Supervisors Mar, Brown, Peskin 10:00 AM Joint City, School District, and City College Select Committee 2nd Friday Supervisors Haney, Walton, Mar (Alt), Commissioners Cook, Collins, Moliga (Alt), 10:00 AM Trustees Randolph, Williams, Selby (Alt) Monday Land Use and Transportation Committee 1:30 PM Supervisors Peskin, Safai, Haney 2nd and 4th Thursday Public Safety and Neighborhood Services Committee 10:00 AM Supervisors Mandelman, Stefani, Walton Monday Rules Committee 10:00 AM Supervisors Ronen, Walton, Mar First-named Supervisor is Chair, Second-named Supervisor is Vice-Chair of the Committee. Volume 114 Number 19 Board of Supervisors Meeting Minutes 6/11/2019 Members Present: Vallie Brown, Sandra Lee Fewer, Matt Haney, Rafael Mandelman, Gordon Mar, Aaron Peskin, Hillary Ronen, Ahsha Safai, Catherine Stefani, Shamann Walton, and Norman Yee The Board of Supervisors of the City and County of San Francisco met in regular session on Tuesday, June 11, 2019, with President Norman Yee presiding. -

Paper Ad Edwin Lee, Mayor Տ SUPPORT $91.73 $73,881.51 Տ OPPOSE ✔ Տ NEUTRAL Տ SUPPORT Տ OPPOSE Տ NEUTRAL

NAME OF FILER I.D. NUMBER REPORT NUMBER San Franciscans for Real Housing Solutions, No on I 1374554 G15-NOI-02 4. Payments of $100 or More Received Number of continuation sheets attached ____________. IF AN INDIVIDUAL, ENTER OCCUPATION AND FULL NAME, STREET ADDRESS AND ZIP CODE OF DONOR CUMULATIVE AMOUNT DATE RECEIVED EMPLOYER AMOUNT RECEIVED (IF COMMITTEE, ALSO ENTER I.D. NUMBER) RECEIVED (ANNUAL) (IF SELF-EMPLOYED, ENTER NAME OF BUSINESS) 09/22/15 California Association of Realtors - Issues N/A $200,000 $237,000 Mobilization Political Action Committee Created: 07/2015 S:\ALL FORMS\Campaign Finance\Current Campaign Finance Forms\SFEC Form 162.docx SFEC Form 162 Revised: 07/2015 NAME OF FILER I.D. NUMBER REPORT NUMBER San Franciscans for Real Housing Solutions, No on I 1374554 G15-NOI-02 2. Electioneering Communications Made (CONTINUED) Continuation sheet ____________ of ____________. DATE DESCRIPTION OF ELECTIONEERING COMMUNICATION NAME OF CANDIDATE & OFFICE POSITION AMOUNT TOTAL/CANDIDATE (ANNUAL) 10/14/15 Mailer Edwin Lee, Mayor տ SUPPORT $345.80 $71,890.64 տ OPPOSE ✔ տ NEUTRAL 10/16/15 Mailer Edwin Lee, Mayor տ SUPPORT $278.85 $72,169.49 տ OPPOSE ✔ տ NEUTRAL 10/18/15 E-mail Blast Edwin Lee, Mayor տ SUPPORT $58.01 $72,227.50 տ OPPOSE ✔ տ NEUTRAL 10/19/15 Mailer Edwin Lee, Mayor տ SUPPORT $345.80 $72,573.30 տ OPPOSE ✔ տ NEUTRAL 10/19/15 Mailer Edwin Lee, Mayor տ SUPPORT $278.85 $72,852.15 տ OPPOSE ✔ տ NEUTRAL 10/21/15 Door Hanger Edwin Lee, Mayor տ SUPPORT $16.12 $72,868.27 տ OPPOSE ✔ տ NEUTRAL 10/21/15 Mailer Edwin Lee, Mayor տ SUPPORT -

Joint City and County Agenda

City and County of San Francisco City Hall 1 Dr. Carlton B. Goodlett Place Meeting Agenda San Francisco, CA 94102-4689 Joint City, School District, and City College Select Committee Supervisors: Matt Haney, Sandra Lee Fewer, Gordon Mar(Alt); Commissioners: Faauuga Moliga, Alison M. Collins, Stevon Cook (Alt); Trustees: Alex Randolph, Shanell Williams, Thea Selby(Alt) Clerk: Erica Major (415) 554-4441 Friday, September 25, 2020 10:00 AM WATCH SF Cable Channel 26, 78 or 99 (depending on provider) WATCH www.sfgovtv.org PUBLIC COMMENT CALL-IN (415) 655-0001 / Meeting ID: Special Meeting ROLL CALL AND ANNOUNCEMENTS AGENDA CHANGES REGULAR AGENDA 1. 200412 [Hearing - Impacts of COVID-19 on San Francisco Unified School District and City College of San Francisco] Sponsor: Haney Hearing regarding how COVID-19 has impacted the schedules, policies, and the provision of services for San Francisco Unified School District (SFUSD) and City College of San Francisco (CCSF); the approach SFUSD and CCSF are exercising to protect both students and staff during the pandemic; how schools are continuing to serve students and families, especially those that are most marginalized; what plans are being made to ensure ongoing educational goals are met; how the City can best support the schools and what resources are required to ensure that they are able to succeed in their vital role as educational institutions; and requesting SFUSD and CCSF to report. 4/21/20; RECEIVED AND ASSIGNED to the Joint City, School District, and City College Select Committee. 4/29/20; REFERRED TO DEPARTMENT. 6/12/20; CONTINUED TO CALL OF THE CHAIR. -

2020 CNY Parade Lineup

2020 Chinese New Year Parade Lineup - SFPD Motorcycles - Chair of the CA State Board of Equalization - Malia Cohen - Senator Scott Wiener - Chinese American International School (CAIS) - Yick Wo Elementary School - State Assemblymember Phil Ting - State Assemblymember David Chiu - San Francisco Bay Area Rapid Transit District (BART) - City Treasurer Jose Cisneros - City Assessor Recorder - Carmen Chu - Ma Tsu Temple of USA - District Attorney - Chesa Boudin - Public Defender - Manohar Raju - California Highway Patrol (CHP) - SFPD Chief William Scott, Command Staff and Central Station Capt. Robert Yick - USF Dons Band - SFFD Fire Chief Jeanine Nicholson & Staff - SFFD Fire truck - SFFD Asian Firefighters Association - SFSD Sheriff Paul Miyamoto - Commodore Sloat YMCA After School Program - President of Board of Supervisors & District 7 - Supervisor Norman Yee - District 3 Supervisor - Aaron Peskin - District 1 Supervisor - Sandra Lee Fewer - Twitter - District 11 Supervisor - Ahsha Safai - District 9 Supervisor - Hillary Ronen - Meyerholz/Cupertino Language Immersion Program - District 6 Supervisor - Matt Haney - District 2 Supervisor - Catherine Stefani - West County Mandarin School - District 10 Supervisor - Shamann Walton - District 4 Supervisor - Gordon Mar - District 8 Supervisor - Rafael Mandelman - District 5 Supervisor - Dean Preston - CCSF Chancellor Mark Rocha - Oakland Fire Deparment Fire truck - Oakland Firefighters Random Acts - 100 ethnic-costumed performers by Huaxing Arts Groups - Grand Marshal - Norman Fong - West Coast Lion Dance Troupe - Southwest Airlines - Archbishop Riordan High School Crusader Marching Band - Orchard School Asian Cultural Dance Troupe - SF Mayor London Breed - Loong Mah Sing See Wui - Alice Fong Yu, Alternative School - President of Chinese Chamber of Commerce - Kenny Tse - CCC, CCBA and Chinese Hospital/CCHP - St. Mary's Drum & Bell Corps - St.