Full Text (PDF)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pay TV in Australia Markets and Mergers

Pay TV in Australia Markets and Mergers Cento Veljanovski CASE ASSOCIATES Current Issues June 1999 Published by the Institute of Public Affairs ©1999 by Cento Veljanovski and Institute of Public Affairs Limited. All rights reserved. First published 1999 by Institute of Public Affairs Limited (Incorporated in the ACT)␣ A.C.N.␣ 008 627 727 Head Office: Level 2, 410 Collins Street, Melbourne, Victoria 3000, Australia Phone: (03) 9600 4744 Fax: (03) 9602 4989 Email: [email protected] Website: www.ipa.org.au Veljanovski, Cento G. Pay TV in Australia: markets and mergers Bibliography ISBN 0 909536␣ 64␣ 3 1.␣ Competition—Australia.␣ 2.␣ Subscription television— Government policy—Australia.␣ 3.␣ Consolidation and merger of corporations—Government policy—Australia.␣ 4.␣ Trade regulation—Australia.␣ I.␣ Title.␣ (Series: Current Issues (Institute of Public Affairs (Australia))). 384.5550994 Opinions expressed by the author are not necessarily endorsed by the Institute of Public Affairs. Printed by Impact Print, 69–79 Fallon Street, Brunswick, Victoria 3056 Contents Preface v The Author vi Glossary vii Chapter One: Introduction 1 Chapter Two: The Pay TV Picture 9 More Choice and Diversity 9 Packaging and Pricing 10 Delivery 12 The Operators 13 Chapter Three: A Brief History 15 The Beginning 15 Satellite TV 19 The Race to Cable 20 Programming 22 The Battle with FTA Television 23 Pay TV Finances 24 Chapter Four: A Model of Dynamic Competition 27 The Basics 27 Competition and Programme Costs 28 Programming Choice 30 Competitive Pay TV Systems 31 Facilities-based -

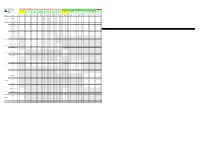

SI Allocations

Free TV Australia DTTB SI Register Transport Stream Service Information for Television Market Area All values are hexadecimal Issue 15 Date: October 2020 Western Australia Tasmania Northern Territory Remote Remote Queensland, Mandurah (Turner NSW, Vic, SA, Tas Perth Bunbury Albany Remote Hobart Launceston Darwin Alice Springs Northern Territory Hill) (See Note 3) (See Notes 1 and 2) (See notes 1 and 2) LCN Broadcaster Service Name SID SID SID SID SID SID SID SID SID SID SID NID NID NID NID NID NID NID NID NID NID NID TSID TSID TSID TSID TSID TSID TSID TSID TSID TSID TSID ONID ONID ONID ONID ONID ONID ONID ONID ONID ONID (dec) ONID 3201 3239 0261 1010 3256 0263 1010 3256 0263 1010 3256 0263 1010 3256 0263 1010 325B 0271 1010 3257 0273 1010 325C 0281 1010 325B 0283 ABC1 2 02E1 02E1 02E1 02E1 02E1 0271 0291 0281 02F1 ABC News 24 24 02E0 02E0 02E0 02E0 02E0 0270 0290 0280 02F0 ABC ABC1 21 02E3 02E3 02E3 02E3 02E3 0273 0293 0283 02F3 ABC2 / ABC4 22 02E2 02E2 02E2 02E2 02E2 0272 0292 0282 02F2 ABC3 23 02E4 02E4 02E4 02E4 02E4 0274 0294 0284 02F4 ABC Dig Music 200 02E6 02E6 02E6 02E6 02E6 0276 0296 0286 02F6 ABC Jazz 201 02E7 02E7 02E7 02E7 02E7 0277 0297 0287 02F7 3202 3202 0320 3202 3202 03A0 3202 3202 03A0 3202 3202 03A0 3202 3202 03A0 3202 3202 0380 3202 3202 0380 3202 3202 0360 SBS ONE 3 0321 03A1 03A1 03A1 03A1 0381 0381 0361 SBS ONE HD 30 0325 03A5 03A5 03A5 03A5 0385 0385 0365 SBS VICELAND HD 31 0326 03A6 03A6 03A6 03A6 0386 0386 0366 SBS World Movies 32 0327 03A7 03A7 03A7 03A7 0387 0387 0367 SBS Food 33 0323 03A3 03A3 03A3 03A3 0383 -

65293 ; 4-'Fvbo

SDMS Document ' 1 SfV6^ n ! 65293 ; 4-'fVBO g!B ANALYTICAL DATA REPORT PACKAGE for m NORTH SEA LANDFILL PART lit OCTOBER 1987 01 > Submitted by: o o H2yH LABS, INC, ' HOLZMACHER, McLENDON and MURRELL. P.C. ^ Consulting Englnaers. Environmental Sclenllsls, Architects and planners <<> ^^ Melville, N.Y. RIverhead, N.Y. FalrMeld, N.J. T f| t> fr\jfA•i iJKL/ ^ mV l LABSI.MD9| , IPIVINC« . 97SBItO>^HOaOMfflOAO,MELVILLE. NY. 11747 •S16-«»4-304 i^ __ I: HOI^MACHER McLENDON and MURREU, P.C • ENVIRONMENTAL Mid tNOUSmiAL ANALYTICAL SERVICE u ICP tO^VELaxnH CALIBRATION AND SIATISUCS FOR FITIED OJWES. CO PI > o o ts) CO , en , CHAIN Of CUSTODY RECORD rnoJCCT NAUi eoN* MCUAKKr '' TAINIMI %%Kmii 9ATI I TIMI \ 2 tTATtON iOCAPON AlLi «/ \:>PuTuii Ui^f^/Hl^^^"^ It- n^D » • _LL ;< \l ipvtV^ '?.Virv<s< iliAmi JCL. t^igLA ^<DUiPH<ry^r- N'j^yJK^ "To P £A0k<Nl=^ \0 > 'g""vg\.^ 6>^Q.<yfe. >^c>.-\e. -x " ^ e^-AVc*^ \.''\'> ••^} \-'\^i.\'J.f\ VjJvtVtW;. "tVsn;!^. u eU Kvr; <•:•: -V/<."i«- tvl.c-fi.r t^t-TtVs ttx^S \^-t^v<t V,")" 3.-V- c^.V >WT. .SWC,. ^. \^..^J\^„^ r^C T,.). IrrtfifMMMi . i»' • 0«l«/Tlm« ll(C<««<4 byt <P»i«i»*»l fl«NA«l4th«4 ^t ISVMNWt) 0(1*/TVM fl«««l««4l Hmi»M»i»ti ^ A«««l««4 kyt Hirniiiwl MtUn^ihttf btr: ft^«*»««l OtU/TlAM fiK«M<rkf: a^MMi ^ OtM/TbM AMtU«« !•> L#b«f tlMr by I 0*1* /TWn* A««M«kf:' N ..J 9881 300 V3S ;^ 1^- CHAIN OF CUSTODY RECORD ': I• fMilH/O. -

Downloadable Search-Based Applications and Portals

QuickLinks -- Click here to rapidly navigate through this document As filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission on May 10, 2005 UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 10-Q ☒ QUARTERLY REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the Quarterly Period Ended March 31, 2005 or o TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the transition period from to Commission File No. 0-20570 IAC/INTERACTIVECORP (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) Delaware 59-2712887 (State or other jurisdiction of (I.R.S. Employer incorporation or organization) Identification No.) 152 West 57th Street, New York, New York 10019 (Address of Registrant's principal executive offices) (212) 314-7300 (Registrant's telephone number, including area code) Indicate by check mark whether the Registrant (1) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the registrant was required to file such reports), and (2) has been subject to such filing requirements for the past 90 days. Yes ☒ No o Indicate by check mark whether the registrant is an accelerated filer (as defined in Rule 12b-2 of the Exchange Act). Yes ☒ No o As of April 25, 2005, the following shares of the Registrant's common stock were outstanding: Common Stock, including 227,437 shares of restricted stock 599,616,946 Class B Common Stock 64,629,996 Total outstanding Common Stock 664,246,942 The aggregate market value of the voting common stock held by non-affiliates of the Registrant as of April 25, 2005 was $10,375,299,426. -

SI Allocations

Free TV Australia DTTB SI Register Transport Stream Service Information for Television Market Area All values are hexadecimal Issue 13 Date: September 2019 Victoria South Australia NSW Bendigo / Goulburn Valley Upper Murray Western Victoria Eyre Peninsula (Port Melbourne Gippsland Mildura Adelaide Mt. Gambier Riverland Spencer Gulf Broken Hill Swan Hill (Shepparton) (Albury) (Ballarat) Augusta) LCN Broadcaster Service Name SID SID SID SID SID SID SID SID SID SID SID SID SID NID NID NID NID NID NID NID NID NID NID NID NID NID TSID TSID TSID TSID TSID TSID TSID TSID TSID TSID TSID TSID TSID ONID ONID ONID ONID ONID ONID ONID ONID ONID ONID ONID ONID (dec) ONID 1010 321B 0231 1010 3253 0233 1010 3253 0233 1010 3253 0233 1010 3253 0233 1010 3253 0233 1010 3253 0233 1010 322F 0251 1010 3255 0253 1010 3255 0253 1010 3255 0253 1010 3255 0253 1010 3252 0223 ABC1 2 0231 02B1 02B1 02B1 02B1 02B1 02B1 0251 02D1 02D1 02D1 02D1 02A1 ABC News 24 24 0230 02B0 02B0 02B0 02B0 02B0 02B0 0250 02D0 02D0 02D0 02D0 02A0 0233 02B3 02B3 02B3 02B3 02B3 02B3 0253 02D3 02D3 02D3 02D3 02A3 ABC ABC1 21 ABC2 / ABC4 22 0232 02B2 02B2 02B2 02B2 02B2 02B2 0252 02D2 02D2 02D2 02D2 02A2 ABC3 23 0234 02B4 02B4 02B4 02B4 02B4 02B4 0254 02D4 02D4 02D4 02D4 02A4 ABC Dig Music 200 0236 02B6 02B6 02B6 02B6 02B6 02B6 0256 02D6 02D6 02D6 02D6 02A6 ABC Jazz 201 0237 02B7 02B7 02B7 02B7 02B7 02B7 0257 02D7 02D7 02D7 02D7 02A7 3202 3202 0310 3202 3202 0370 3202 3202 0370 3202 3202 0370 3202 3202 0370 3202 3202 0370 3202 3202 0370 3202 3202 0340 3202 3202 0390 3202 3202 0390 3202 -

Administrative Appeals Tribunal

*gaAg-k Administrative Appeals Tribunal ADMINISTRATIVE APPEALS TRIBUNAL No: 2010/4470 GENERAL ADMINISTRATIVE DIVISION Re: Australian Subscription Television and Radio Association Applicant And: Australian Human Rights Commission Respondent And: Media Access Australia Other Party TRIBUNAL: Ms G Ettinger, Senior Member DATE: 30 April 2012 PLACE: Sydney In accordance with section 34D(1) of the Administrative Appeals Tribunal Act 1975: in the course of an alternative dispute resolution process, the parties have reached an agreement as to the terms of a decision of the Tribunal that is acceptable to the parties; and the terms of the agreement have been reduced to writing, signed by or on behalf of the parties and lodged with the Tribunal; and the Tribunal is satisfied that a decision in those terms is within the powers of the Tribunal and is appropriate to make. Accordingly the Tribunal sets aside the decision of the Respondent and substitutes a decision that reflects the conditions jointly agreed by the parties and annexed to this decision. [ IN THE ADMINISTRATIVE APPEALS TRIBUNAL File Number 2010/4470 AUSTRALIAN SUBSCRIPTION TELEVISION AND RADIO ASSOCIATION Applicant AND AUSTRALIAN HUMAN RIGHTS COMMISSION Respondent AND MEDIA ACCESS AUSTRALIA Joined Party BY CONSENT THE TRIBUNAL MAKES THE FOLLOWING ORDERS PURSUANT TO SECTION 55 OF THE DISABILITY DISCRIMINATION ACT 1992 (CTI1): 1. Exemption 1.1 Each of the Entities is exempt from the operation of ss 5, 6, 7, 8,24, 122 and 123 of the Disability Discrimination Act 1992 (Cth) in respect of the provision of Captioning from the date of this Order until 30 June 2015 on the condition that it complies with the conditions outlined below that are applicable to it by reason of its operation as either a Channel Provider or a Platform. -

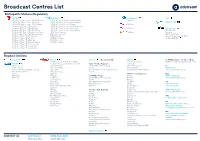

Broadcast Centres List

Broadcast Centres List Metropolita Stations/Regulatory 7 BCM Nine (NPC) Ten Network ABC 7HD & SD/ 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Melbourne 9HD & SD/ 9Go! / 9Gem / 9Life Adelaide Ten (10) 7HD & SD/ 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Perth 9HD & SD/ 9Go! / 9Gem / 9Life Brisbane FREE TV CAD 7HD & SD/ 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Adelaide 9HD & SD/ 9Go! / 9Gem / Darwin 10 Peach 7 / 7mate HD/ 7two / 7Flix Sydney 9HD & SD/ 9Go! / 9Gem / 9Life Melbourne 7 / 7mate HD/ 7two / 7Flix Brisbane 9HD & SD/ 9Go! / 9Gem / 9Life Perth 10 Bold SBS National 7 / 7mate HD/ 7two / 7Flix Gold Coast 9HD & SD/ 9Go! / 9Gem / 9Life Sydney SBS HD/ SBS 7 / 7mate HD/ 7two / 7Flix Sunshine Coast GTV Nine Melbourne 10 Shake Viceland 7 / 7mate HD/ 7two / 7Flix Maroochydore NWS Nine Adelaide SBS Food Network 7 / 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Townsville NTD 8 Darwin National Indigenous TV (NITV) 7 / 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Cairns QTQ Nine Brisbane WORLD MOVIES 7 / 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Mackay STW Nine Perth 7 / 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Rockhampton TCN Nine Sydney 7 / 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Toowoomba 7 / 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Townsville 7 / 7mate / 7two / 7Flix Wide Bay Regional Stations Imparaja TV Prime 7 SCA TV Broadcast in HD WIN TV 7 / 7TWO / 7mate / 9 / 9Go! / 9Gem 7TWO Regional (REG QLD via BCM) TEN Digital Mildura Griffith / Loxton / Mt.Gambier (SA / VIC) NBN TV 7mate HD Regional (REG QLD via BCM) SC10 / 11 / One Regional: Ten West Central Coast AMB (Nth NSW) Central/Mt Isa/ Alice Springs WDT - WA regional VIC Coffs Harbour AMC (5th NSW) Darwin Nine/Gem/Go! WIN Ballarat GEM HD Northern NSW Gold Coast AMD (VIC) GTS-4 -

Channel-Guide-27-May-2018.Pdf

FIND ALL OF YOUR FAVOURITE CHANNEL GUIDE CHANNELS DIGITAL +2 DIGITAL +2 DIGITAL +2 § 111 funny .....................................111 154 Discovery Turbo .............. 634/620* 635/640* MTV Dance .............................. 804 13th STREET ........................118/117* 160 Disney Channel ......................... 707 MTV Music ............................... 803 On channels 831-860, you can access 30 ad-free A&E ........................................... 122 614/611* Disney Junior ............................ 709 MUTV ........................................ 518 audio channels playing your favourite music, Disney Movies ................. 404/400* 415/401* Action Movies ................. 406/409* 412/411* National Geographic ......... 610/613* 641 news and current affairs with no interruptions. Adults Only ............................ 960-1 Disney XD ................................. 708 foxtel tunes is part of your ENTERTAINMENT pack˚ Nat Geo WILD .................. 616/622* Al Jazeera English..................... 651 E! .............................................. 125 MAX 70s Hits Animal Planet ................... 615/621* ESPN ........................................ 508 NHK World ............................... 656 MAX 80s Hits Antenna .................................... 941 ESPN2 ...................................... 509 Nickelodeon ............................. 701 MAX 90s Hits Arena .................................105/112* 151 Eurosport ................................... 511 Nick Jr. ..................................... -

Iac/Interactivecorp

IAC/INTERACTIVECORP FORM 10-K (Annual Report) Filed 03/16/05 for the Period Ending 12/31/04 Address 152 WEST 57TH ST 42ND FLOOR NEW YORK, NY 10019 Telephone 2123147300 CIK 0000891103 Symbol IACI SIC Code 5990 - Retail Stores, Not Elsewhere Classified Industry Retail (Catalog & Mail Order) Sector Services Fiscal Year 12/31 http://www.edgar-online.com © Copyright 2008, EDGAR Online, Inc. All Rights Reserved. Distribution and use of this document restricted under EDGAR Online, Inc. Terms of Use. QuickLinks -- Click here to rapidly navigate through this document As filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission on March 16, 2005 UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 10-K ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the Fiscal Year Ended December 31, 2004 IAC/INTERACTIVECORP (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) Commission File No. 0-20570 Delaware 59 -2712887 (State or other jurisdiction of (IRS Employer Identification No.) incorporation or organization) 152 West 57th Street, New York, New York 10019 (Address of Registrant's principal executive offices) (Zip Code) (212) 314-7300 (Registrant's telephone number, including area code) Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: None Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: Common Stock, $.01 par value Warrants to Acquire One Share of Common Stock Warrants to Acquire 1.93875 Shares of Common Stock Indicate by check mark whether the Registrant (1) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the Registrant was required to file such reports) and (2) has been subject to such filing requirements for the past 90 days. -

SOURCE NAME T*GE 1

mmimmmm TEMPORARY PRELIMINARY DECREE ON MUSSELLSHELL RIVER ABOVE ROWDUP - BASIN «V\ 04/?7/85 INDEX OF CLAIMS BT SOURCE NAME t*GE 1 FLOW PRIORITY . POINT OF DIVERSION . HATS! RiqfT IP lfi£ RATE DATE 8TR SEC SFC Tlf RCg O UT SOURCE MAX OWNER NAME 40* -V-192521-00 ST r 07/19/1883 S2N2 Z7 06M 13E MN USES CREEK SLBtUE RANCHES INC t&^msm—^ -mm wgHBMgg ®&m. SSWM 40* -W-110013-00 IR 2.50 C 05/31/1887 NUSESU 11 QSN 12E S6 ASCS CREEK MCFMLAND WHITE MMCH INC 40* -y-iggwa-pp p" zs.oo 6 .ijQ]'???6 wBag* 32 06N 13E w Ages WEEK AFRICAN FORK RANCH ^ 0T7OT71935SBMM 6u5Ni3fc5GMwEStHEeKIHERZC^ MM -W-198469-00 ST 01/01/1935 NUNENE 11 05* 12E 96 ACNES C*E0< AMERICAN FORK MNCH 40* -W-gg965-00 IS 7.09 C 05/31/1887 SWNHNU 36 QW 096 Wp ALABAUBH CHER 8HAWPE RANCH CO *DR~=W=ZQ3575=DD~IR' *.!/ c o»/iv/ieov NEHBHE~Z5~DBnj§Ewt ALABMWH u<ttK wumot, I>«IIL mwut JNL ZIKMUND ROSE* C 40* -w-go296g-po re 3.18 c OS/DI/IBW NENWSU 27 qtw 09E HE ALABHUBH WEEK gAwce gwcw co *u* -W-iVBJ/1-OU ST TO7T37TBW Sii <!/ l38t WE NE ALAHUUH CUfEK OUNOE MNCfnCO *OA -W-202961-00 IR 4.17 C 10/15/1889 NUNESU Zlt '08H 09E «t ALABAUQH CKEK GRAMRE MMCH CO «OA -U-203576-00 IR .38 C 05/11/1891 NUSENW 30 08N 096. WE ALABAU6H CHEEK T*^JL ""*" """"Bltiy *OA -0-057555-00 ST 06/01/1905 NENENU 28 08* OSt ME X ALABAUGH CREEK US DEPT OF AGRICULTURE RMEST S «Q* ^*jff7}66-pn ST pg/PJ/igg S2SW 23 TOW WE ME ALASAUgj CREEK Ig DEPT OF AglOI-TW. -

Broadcastasia

www.Broadcast-Asia.com 26 - 28 June 2018 Suntec Singapore CAPTURE THE FUTURE A part of Organised by : Held Alongside : SES BroadcastAsia2018, Asia’s must-attend international event for the pro-audio, film, digital media and broadcasting industries, unveils a brand new look, as a fresh new experience awaits with the launch of ConnecTechAsia! Capture the future and join the industry in showcasing the latest in broadcasting Technologies featured include.. technologies and network with likeminded professionals. To create a better experience for all attendees, BroadcastAsia2018 will have a more targeted layout. Acquisition / Cinematography / Film / Be part of the zone that best represents your company and join industry peers in showcasing your Production company’s latest innovations. • 4K / UHD / HDR • Motion Capture / Virtual • Cameras and Lenses Production • Immersive and VR / AR • Professional Lighting Technologies • Digital Display LEVEL 3 Hospitality Suites • Live production / Remote Hospitality production / Aerial Suites Book a fully-customisable Hospitality Suite on Level 3 to organise exclusive networking functions, conduct production product demonstrations or invite customers for private meetings. A dedicated marketing campaign will also be made available exclusively to companies taking up the Hospitality Suites. Post Production • Animation, VFx / Motion • Music and Sound International Group Pavilions Graphics Libraries • Editing • Subtitling and Spread across the 2 levels of the exhibition, represent your country / group’s expertise and specialisation • Mastering, Duplication Captioning by showcasing your native innovations at the 13 pavilions from China, France, Germany, Italy, Korea, and Conversion • Work flow Solutions Russia, Singapore, Spain, UK and USA / Canada. Contact [email protected] to find out how you can participate as part of the Group Pavilion. -

TVSN Shopping Channel Has Moved - New Arrangements

Information Bulletin Videosat Pty Ltd 2/28 Salisbury Road Hornsby NSW 2077 PO Box 3190 Asquith NSW 2077 Phone (02) 9482 3100 Fax(02) 9482 3999 www.videosat.com.au September 2000 TVSN Shopping Channel Has Moved - New Arrangements - general the beam covers a 500KM wide strip from Background Rockhampton down the east coast of Australia, across As of September 1st 2000, the shopping channel, Victoria and on to Adelaide. The Shopping Channel TVSN is no longer available on the normal Optus TVSN is on this footprint Aurora platform. This platform is the location of all of the Direct to Home Free to Air digital Satellite TV What is needed to receive marketed by Videosat. TVSN? The good news is that TVSN has been and will still be You will need: available on the same satellite housed with the pay TV • Standard Australian Direct to Home Free to Air Digital services and will not be encrypted. That is, a smart Satellite TV System card is not needed to access the service. All new digital systems supplied by Videosat since the end of 1998 will be OK. Background • The dish electronics must be modern dual Polarity. Videosat C750, C770 series, C850, C870 Series LNB’s. The Optus satellite now carries quite a large number Most LNB replacements supplied by Videosat since the of services, all are individually tailored to the end of 1998 will be OK. - Except C700 series. broadcaster’s marketing needs. Basically: • You must be in the footprint area of the Optus High • Free unrestricted access - (no need to use a smart card), performance beam (Pay TV Services) • Free but conditional access requiring a smart card (Our • You will need to reconfigure your satellite receiver to direct to Home Digital Services) add the TVSN channel • Pay services.