Prevalence of Cytoplasmic Actin Mutations in Diffuse Large B

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FLNC Missense Variants in Familial Noncompaction Cardiomyopathy

Cardiogenetics 2019; volume 9:8181 FLNC missense variants than 2 according to current echocardio- in familial noncompaction graphic criteria, or 2.3 on CMR.1,2 Correspondence: Jaap I. van Waning, Approximately 10% of patients diagnosed Department of Clinical Genetics, EE 2038, cardiomyopathy with NCCM have concurrent congenital Erasmus MC, POB 2040, 3000CA Rotterdam, heart defects (CHD).3,4 the Netherlands. Tel.: +3107038388 - Fax: +3107043072. Jaap I. van Waning,1 In 30-40% of cases diagnosed with E-mail: [email protected] Yvonne M. Hoedemaekers,2 NCCM a pathogenic variant can be identi- 2,3 4 Wouter P. te Rijdt, Arne I. Jpma, fied. Around 80% of these pathogenic vari- Acknowledgements: JVW was supported by a Daphne Heijsman,4 Kadir Caliskan,5 ants involve the same sarcomere genes, that grant from the Jaap Schouten Foundation. Elke S. Hoendermis,6 are the major causes for hypertrophic car- WPTR was supported by a Young Talent Program (CVON PREDICT) grant 2017T001 Tineke P. Willems,7 diomyopathy (HCM) and dilated cardiomy- - Dutch Heart Foundation. 8 opathy (DCM), in particular MYH7, Arthur van den Wijngaard, 5,6 3 MYBPC3 and TTN. Filamin C (FLNC) Albert Suurmeijer, Conflict of interest: the authors declare no plays a central role in muscle functioning Marjon A. van Slegtenhorst,1 potential conflict of interest. by maintaining the structural integrity of the Jan D.H. Jongbloed,2 muscle fibers. Pathogenic variants in FLNC Received for publication: 20 March 2019. Danielle F. Majoor-Krakauer,1 2 were found to be associated with a wide Revision received: 29 July 2019. Paul A. -

The Cytoskeleton in Cell-Autonomous Immunity: Structural Determinants of Host Defence

Mostowy & Shenoy, Nat Rev Immunol, doi:10.1038/nri3877 The cytoskeleton in cell-autonomous immunity: structural determinants of host defence Serge Mostowy and Avinash R. Shenoy Medical Research Council Centre of Molecular Bacteriology and Infection (CMBI), Imperial College London, Armstrong Road, London SW7 2AZ, UK. e‑mails: [email protected] ; [email protected] doi:10.1038/nri3877 Published online 21 August 2015 Abstract Host cells use antimicrobial proteins, pathogen-restrictive compartmentalization and cell death in their defence against intracellular pathogens. Recent work has revealed that four components of the cytoskeleton — actin, microtubules, intermediate filaments and septins, which are well known for their roles in cell division, shape and movement — have important functions in innate immunity and cellular self-defence. Investigations using cellular and animal models have shown that these cytoskeletal proteins are crucial for sensing bacteria and for mobilizing effector mechanisms to eliminate them. In this Review, we highlight the emerging roles of the cytoskeleton as a structural determinant of cell-autonomous host defence. 1 Mostowy & Shenoy, Nat Rev Immunol, doi:10.1038/nri3877 Cell-autonomous immunity, which is defined as the ability of a host cell to eliminate an invasive infectious agent, is a first line of defence against microbial pathogens 1 . It relies on antimicrobial proteins, specialized degradative compartments and programmed host cell death 1–3 . Cell- autonomous immunity is mediated by tiered innate immune signalling networks that sense microbial pathogens and stimulate downstream pathogen elimination programmes. Recent studies on host– microorganism interactions show that components of the host cell cytoskeleton are integral to the detection of bacterial pathogens as well as to the mobilization of antibacterial responses (FIG. -

Genetic Mutations and Mechanisms in Dilated Cardiomyopathy

Genetic mutations and mechanisms in dilated cardiomyopathy Elizabeth M. McNally, … , Jessica R. Golbus, Megan J. Puckelwartz J Clin Invest. 2013;123(1):19-26. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI62862. Review Series Genetic mutations account for a significant percentage of cardiomyopathies, which are a leading cause of congestive heart failure. In hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM), cardiac output is limited by the thickened myocardium through impaired filling and outflow. Mutations in the genes encoding the thick filament components myosin heavy chain and myosin binding protein C (MYH7 and MYBPC3) together explain 75% of inherited HCMs, leading to the observation that HCM is a disease of the sarcomere. Many mutations are “private” or rare variants, often unique to families. In contrast, dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) is far more genetically heterogeneous, with mutations in genes encoding cytoskeletal, nucleoskeletal, mitochondrial, and calcium-handling proteins. DCM is characterized by enlarged ventricular dimensions and impaired systolic and diastolic function. Private mutations account for most DCMs, with few hotspots or recurring mutations. More than 50 single genes are linked to inherited DCM, including many genes that also link to HCM. Relatively few clinical clues guide the diagnosis of inherited DCM, but emerging evidence supports the use of genetic testing to identify those patients at risk for faster disease progression, congestive heart failure, and arrhythmia. Find the latest version: https://jci.me/62862/pdf Review series Genetic mutations and mechanisms in dilated cardiomyopathy Elizabeth M. McNally, Jessica R. Golbus, and Megan J. Puckelwartz Department of Human Genetics, University of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois, USA. Genetic mutations account for a significant percentage of cardiomyopathies, which are a leading cause of conges- tive heart failure. -

Defining Functional Interactions During Biogenesis of Epithelial Junctions

ARTICLE Received 11 Dec 2015 | Accepted 13 Oct 2016 | Published 6 Dec 2016 | Updated 5 Jan 2017 DOI: 10.1038/ncomms13542 OPEN Defining functional interactions during biogenesis of epithelial junctions J.C. Erasmus1,*, S. Bruche1,*,w, L. Pizarro1,2,*, N. Maimari1,3,*, T. Poggioli1,w, C. Tomlinson4,J.Lees5, I. Zalivina1,w, A. Wheeler1,w, A. Alberts6, A. Russo2 & V.M.M. Braga1 In spite of extensive recent progress, a comprehensive understanding of how actin cytoskeleton remodelling supports stable junctions remains to be established. Here we design a platform that integrates actin functions with optimized phenotypic clustering and identify new cytoskeletal proteins, their functional hierarchy and pathways that modulate E-cadherin adhesion. Depletion of EEF1A, an actin bundling protein, increases E-cadherin levels at junctions without a corresponding reinforcement of cell–cell contacts. This unexpected result reflects a more dynamic and mobile junctional actin in EEF1A-depleted cells. A partner for EEF1A in cadherin contact maintenance is the formin DIAPH2, which interacts with EEF1A. In contrast, depletion of either the endocytic regulator TRIP10 or the Rho GTPase activator VAV2 reduces E-cadherin levels at junctions. TRIP10 binds to and requires VAV2 function for its junctional localization. Overall, we present new conceptual insights on junction stabilization, which integrate known and novel pathways with impact for epithelial morphogenesis, homeostasis and diseases. 1 National Heart and Lung Institute, Faculty of Medicine, Imperial College London, London SW7 2AZ, UK. 2 Computing Department, Imperial College London, London SW7 2AZ, UK. 3 Bioengineering Department, Faculty of Engineering, Imperial College London, London SW7 2AZ, UK. 4 Department of Surgery & Cancer, Faculty of Medicine, Imperial College London, London SW7 2AZ, UK. -

Key Pathways Involved in Prostate Cancer Based on Gene Set Enrichment Analysis and Meta Analysis

Key pathways involved in prostate cancer based on gene set enrichment analysis and meta analysis Q.Y. Ning1, J.Z. Wu1, N. Zang2, J. Liang3, Y.L. Hu2 and Z.N. Mo4 1Department of Infection, The First Affiliated Hospital of Guangxi Medical University, Nanning, Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region, China 2The Medical Scientific Research Centre, Guangxi Medical University, Nanning, Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region, China 3Department of Biology Technology, Guilin Medical University, Guilin, Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region, China 4Department of Urology, the First Affiliated Hospital of Guangxi Medical University, Nanning, Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region, China Corresponding authors: Y.L. Hu / Z.N. Mo E-mail: [email protected] / [email protected] Genet. Mol. Res. 10 (4): 3856-3887 (2011) Received June 7, 2011 Accepted October 14, 2011 Published December 14, 2011 DOI http://dx.doi.org/10.4238/2011.December.14.10 ABSTRACT. Prostate cancer is one of the most common male malignant neoplasms; however, its causes are not completely understood. A few recent studies have used gene expression profiling of prostate cancer to identify differentially expressed genes and possible relevant pathways. However, few studies have examined the genetic mechanics of prostate cancer at the pathway level to search for such pathways. We used gene set enrichment analysis and a meta-analysis of six independent studies after standardized microarray preprocessing, which increased concordance between these gene datasets. Based on gene set enrichment analysis, there were 12 down- and 25 up-regulated mixing pathways in more than two tissue datasets, while there were two down- and two up-regulated mixing pathways in three cell datasets. -

Cardiomyopathy

UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA PHYSICIANS OUTREACH LABS Submit this form along with the appropriate MOLECULAR DIAGNOSTICS (612) 273-8445 Molecular requisition (Molecular Diagnostics or DATE: TIME COLLECTED: PCU/CLINIC: Molecular NGS Oncology). AM PM PATIENT IDENTIFICATION DIAGNOSIS (Dx) / DIAGNOSIS CODES (ICD-9) - OUTPATIENTS ONLY SPECIMEN TYPE: o Blood (1) (2) (3) (4) PLEASE COLLECT 5-10CC IN ACD-A OR EDTA TUBE ORDERING PHYSICIAN NAME AND PHONE NUMBER: Tests can be ordered as a full panel, or by individual gene(s). Please contact the genetic counselor with any questions at 612-624-8948 or by pager at 612-899-3291. _______________________________________________ Test Ordered- EPIC: Next generation sequencing(Next Gen) Sunquest: NGS Brugada syndrome DMD Aortopathy Full panel DNAJC19 SCN5A DSP Full panel GPD1L Cardiomyopathy, familial MYH11 CACNA1C hypertrophic ACTA2 SCN1B Full panel MYLK KCNE3 ANKRD1 FBN2 SCN3B JPH2 SLC2A10 HCN4 PRKAG2 COL5A2 MYH7 COL5A1 MYL2 COL3A1 Cardiomyopathy ACTC1 CBS Cardiomyopathy, dilated CSRP3 SMAD3 Full panel TNNC1 TGFBR1 LDB3 MYH6 TGFBR2 LMNA VCL FBN1 ACTN2 MYOZ2 Arrhythmogenic right ventricular DSG2 PLN dysplasia NEXN CALR3 TNNT2 TNNT2 NEXN Full panel RBM20 TPM1 TGFB3 SCN5A MYBPC3 DSG2 MYH6 TNNI3 DSC2 TNNI3 MYL3 JUP TTN TTN RYR2 BAG3 MYLK2 TMEM43 DES Cardiomyopathy, familial DSP CRYAB EYA4 restrictive PKP2 Full panel Atrial fibrillation LAMA4 MYPN TNNI3 SGCD MYPN TNNT2 Full panel CSRP3 SCN5A MYBPC3 GJA5 TCAP ABCC9 ABCC9 SCN1B PLN SCN2B ACTC1 KCNQ1 MYH7 KCNE2 TMPO NPPA VCL NPPA TPM1 KCNA5 TNNC1 KCNJ2 GATAD1 4/1/2014 -

Identification of an FHL1 Protein Complex Containing Gamma-Actin and Non-Muscle Myosin IIB by Analysis of Protein-Protein Interactions

Identification of an FHL1 Protein Complex Containing Gamma-Actin and Non-Muscle Myosin IIB by Analysis of Protein-Protein Interactions Lili Wang1*, Jianing Miao1, Lianyong Li2,DiWu1, Yi Zhang1, Zhaohong Peng1, Lijun Zhang2, Zhengwei Yuan1, Kailai Sun3 1 Key Laboratory of Health ~Ministry for Congenital Malformation, Shengjing Hospital, China Medical University, Shenyang, China, 2 Department of Pediatric Surgery, Shengjing Hospital, China Medical University, Shenyang, China, 3 Department of Medical Genetics, China Medical University, Shenyang, China Abstract FHL1 is multifunctional and serves as a modular protein binding interface to mediate protein-protein interactions. In skeletal muscle, FHL1 is involved in sarcomere assembly, differentiation, growth, and biomechanical stress. Muscle abnormalities may play a major role in congenital clubfoot (CCF) deformity during fetal development. Thus, identifying the interactions of FHL1 could provide important new insights into its functional role in both skeletal muscle development and CCF pathogenesis. Using proteins derived from rat L6GNR4 myoblastocytes, we detected FHL1 interacting proteins by immunoprecipitation. Samples were analyzed by liquid chromatography mass spectrometry (LC-MS). Dynamic gene expression of FHL1 was studied. Additionally, the expression of the possible interacting proteins gamma-actin and non- muscle myosin IIB, which were isolated from the lower limbs of E14, E15, E17, E18, E20 rat embryos or from adult skeletal muscle was analyzed. Potential interacting proteins isolated from E17 lower limbs were verified by immunoprecipitation, and co-localization in adult gastrocnemius muscle was visualized by fluorescence microscopy. FHL1 expression was associated with skeletal muscle differentiation. E17 was found to be the critical time-point for skeletal muscle differentiation in the lower limbs of rat embryos. -

Novel Pathogenic Variants in Filamin C Identified in Pediatric Restrictive Cardiomyopathy

Novel pathogenic variants in filamin C identified in pediatric restrictive cardiomyopathy Jeffrey Schubert1, 2, Muhammad Tariq3, Gabrielle Geddes4, Steven Kindel4, Erin M. Miller5, and Stephanie M. Ware2. 1 Department of Molecular Genetics, Microbiology, and Biochemistry, University of Cincinnati College of Medicine, Cincinnati, OH; 2 Departments of Pediatrics and Medical and Molecular Genetics, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, IN; 3 Faculty of Applied Medical Science, University of Tabuk, Tabuk, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia; 4Department of Pediatrics, Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, WI; 5Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, Cincinnati, OH. Correspondence: Stephanie M. Ware, MD, PhD Department of Pediatrics Indiana University School of Medicine 1044 W. Walnut Street Indianapolis, IN 46202 Telephone: 317 274-8939 Email: [email protected] Grant Sponsor: The project was supported by the Children’s Cardiomyopathy Foundation (S.M.W.), an American Heart Association Established Investigator Award 13EIA13460001 (S.M.W.) and an AHA Postdoctoral Fellowship Award 12POST10370002 (M.T.). ___________________________________________________________________ This is the author's manuscript of the article published in final edited form as: Schubert, J., Tariq, M., Geddes, G., Kindel, S., Miller, E. M., & Ware, S. M. (2018). Novel pathogenic variants in filamin C identified in pediatric restrictive cardiomyopathy. Human Mutation, 0(ja). https://doi.org/10.1002/humu.23661 Abstract Restrictive cardiomyopathy (RCM) is a rare and distinct form of cardiomyopathy characterized by normal ventricular chamber dimensions, normal myocardial wall thickness, and preserved systolic function. The abnormal myocardium, however, demonstrates impaired relaxation. To date, dominant variants causing RCM have been reported in a small number of sarcomeric or cytoskeletal genes, but the genetic causes in a majority of cases remain unexplained especially in early childhood. -

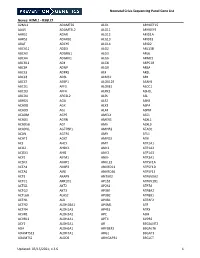

NICU Gene List Generator.Xlsx

Neonatal Crisis Sequencing Panel Gene List Genes: A2ML1 - B3GLCT A2ML1 ADAMTS9 ALG1 ARHGEF15 AAAS ADAMTSL2 ALG11 ARHGEF9 AARS1 ADAR ALG12 ARID1A AARS2 ADARB1 ALG13 ARID1B ABAT ADCY6 ALG14 ARID2 ABCA12 ADD3 ALG2 ARL13B ABCA3 ADGRG1 ALG3 ARL6 ABCA4 ADGRV1 ALG6 ARMC9 ABCB11 ADK ALG8 ARPC1B ABCB4 ADNP ALG9 ARSA ABCC6 ADPRS ALK ARSL ABCC8 ADSL ALMS1 ARX ABCC9 AEBP1 ALOX12B ASAH1 ABCD1 AFF3 ALOXE3 ASCC1 ABCD3 AFF4 ALPK3 ASH1L ABCD4 AFG3L2 ALPL ASL ABHD5 AGA ALS2 ASNS ACAD8 AGK ALX3 ASPA ACAD9 AGL ALX4 ASPM ACADM AGPS AMELX ASS1 ACADS AGRN AMER1 ASXL1 ACADSB AGT AMH ASXL3 ACADVL AGTPBP1 AMHR2 ATAD1 ACAN AGTR1 AMN ATL1 ACAT1 AGXT AMPD2 ATM ACE AHCY AMT ATP1A1 ACO2 AHDC1 ANK1 ATP1A2 ACOX1 AHI1 ANK2 ATP1A3 ACP5 AIFM1 ANKH ATP2A1 ACSF3 AIMP1 ANKLE2 ATP5F1A ACTA1 AIMP2 ANKRD11 ATP5F1D ACTA2 AIRE ANKRD26 ATP5F1E ACTB AKAP9 ANTXR2 ATP6V0A2 ACTC1 AKR1D1 AP1S2 ATP6V1B1 ACTG1 AKT2 AP2S1 ATP7A ACTG2 AKT3 AP3B1 ATP8A2 ACTL6B ALAS2 AP3B2 ATP8B1 ACTN1 ALB AP4B1 ATPAF2 ACTN2 ALDH18A1 AP4M1 ATR ACTN4 ALDH1A3 AP4S1 ATRX ACVR1 ALDH3A2 APC AUH ACVRL1 ALDH4A1 APTX AVPR2 ACY1 ALDH5A1 AR B3GALNT2 ADA ALDH6A1 ARFGEF2 B3GALT6 ADAMTS13 ALDH7A1 ARG1 B3GAT3 ADAMTS2 ALDOB ARHGAP31 B3GLCT Updated: 03/15/2021; v.3.6 1 Neonatal Crisis Sequencing Panel Gene List Genes: B4GALT1 - COL11A2 B4GALT1 C1QBP CD3G CHKB B4GALT7 C3 CD40LG CHMP1A B4GAT1 CA2 CD59 CHRNA1 B9D1 CA5A CD70 CHRNB1 B9D2 CACNA1A CD96 CHRND BAAT CACNA1C CDAN1 CHRNE BBIP1 CACNA1D CDC42 CHRNG BBS1 CACNA1E CDH1 CHST14 BBS10 CACNA1F CDH2 CHST3 BBS12 CACNA1G CDK10 CHUK BBS2 CACNA2D2 CDK13 CILK1 BBS4 CACNB2 CDK5RAP2 -

Cldn19 Clic2 Clmp Cln3

NewbornDx™ Advanced Sequencing Evaluation When time to diagnosis matters, the NewbornDx™ Advanced Sequencing Evaluation from Athena Diagnostics delivers rapid, 5- to 7-day results on a targeted 1,722-genes. A2ML1 ALAD ATM CAV1 CLDN19 CTNS DOCK7 ETFB FOXC2 GLUL HOXC13 JAK3 AAAS ALAS2 ATP1A2 CBL CLIC2 CTRC DOCK8 ETFDH FOXE1 GLYCTK HOXD13 JUP AARS2 ALDH18A1 ATP1A3 CBS CLMP CTSA DOK7 ETHE1 FOXE3 GM2A HPD KANK1 AASS ALDH1A2 ATP2B3 CC2D2A CLN3 CTSD DOLK EVC FOXF1 GMPPA HPGD K ANSL1 ABAT ALDH3A2 ATP5A1 CCDC103 CLN5 CTSK DPAGT1 EVC2 FOXG1 GMPPB HPRT1 KAT6B ABCA12 ALDH4A1 ATP5E CCDC114 CLN6 CUBN DPM1 EXOC4 FOXH1 GNA11 HPSE2 KCNA2 ABCA3 ALDH5A1 ATP6AP2 CCDC151 CLN8 CUL4B DPM2 EXOSC3 FOXI1 GNAI3 HRAS KCNB1 ABCA4 ALDH7A1 ATP6V0A2 CCDC22 CLP1 CUL7 DPM3 EXPH5 FOXL2 GNAO1 HSD17B10 KCND2 ABCB11 ALDOA ATP6V1B1 CCDC39 CLPB CXCR4 DPP6 EYA1 FOXP1 GNAS HSD17B4 KCNE1 ABCB4 ALDOB ATP7A CCDC40 CLPP CYB5R3 DPYD EZH2 FOXP2 GNE HSD3B2 KCNE2 ABCB6 ALG1 ATP8A2 CCDC65 CNNM2 CYC1 DPYS F10 FOXP3 GNMT HSD3B7 KCNH2 ABCB7 ALG11 ATP8B1 CCDC78 CNTN1 CYP11B1 DRC1 F11 FOXRED1 GNPAT HSPD1 KCNH5 ABCC2 ALG12 ATPAF2 CCDC8 CNTNAP1 CYP11B2 DSC2 F13A1 FRAS1 GNPTAB HSPG2 KCNJ10 ABCC8 ALG13 ATR CCDC88C CNTNAP2 CYP17A1 DSG1 F13B FREM1 GNPTG HUWE1 KCNJ11 ABCC9 ALG14 ATRX CCND2 COA5 CYP1B1 DSP F2 FREM2 GNS HYDIN KCNJ13 ABCD3 ALG2 AUH CCNO COG1 CYP24A1 DST F5 FRMD7 GORAB HYLS1 KCNJ2 ABCD4 ALG3 B3GALNT2 CCS COG4 CYP26C1 DSTYK F7 FTCD GP1BA IBA57 KCNJ5 ABHD5 ALG6 B3GAT3 CCT5 COG5 CYP27A1 DTNA F8 FTO GP1BB ICK KCNJ8 ACAD8 ALG8 B3GLCT CD151 COG6 CYP27B1 DUOX2 F9 FUCA1 GP6 ICOS KCNK3 ACAD9 ALG9 -

Tumor Suppressor and DNA Damage Response Panel 2

Tumor suppressor and DNA damage response panel 2 (55 analytes) Gene Symbol Target protein name UniProt ID (& link) Modification* *blanks mean the assay detects the ACT Actin; ACTA2 ACTA1 ACTB ACTG1 ACTC1 ACTG2 Q562L2 non‐modified peptide sequence CASC5 cancer susceptibility candidate 5 Q8NG31 pS767 CASC5 cancer susceptibility candidate 5 Q8NG31 CASP3 caspase 3, apoptosis‐related cysteine peptidase P42574 pS26 CDC25B cell division cycle 25 homolog B (S. pombe) P30305 pS16 CDC25B cell division cycle 25 homolog B (S. pombe) P30305 pS323 CDC25B cell division cycle 25 homolog B (S. pombe) P30305 CDC25C cell division cycle 25 homolog B (S. pombe) P30307 pS216 CDC25C cell division cycle 25 homolog B (S. pombe) P30307 CDCA8 cell division cycle associated 8 Q53HL2 pT16 CDK1 cyclin‐dependent kinase 1 P06493 pT161 CDK1 cyclin‐dependent kinase 1 P06493 CDK7 cyclin‐dependent kinase 7 P50613 pT17 CHEK1 CHK1 checkpoint homolog (S. pombe) O14757 pS286 CHEK2 CHK2 checkpoint homolog (S. pombe) O96017 pS379 CHEK2 CHK2 checkpoint homolog (S. pombe) O96017 pT387 CHEK2 CHK2 checkpoint homolog (S. pombe) O96017 GAPDH Glyceraldehyde‐3‐phosphate dehydrogenase P04406 LAT linker for activation of T cells O43561 pS224 LMNB1 lamin B1 P20700 pT2; pS23 LMNB1 lamin B1 P20700 pT2 LMNB1 lamin B1 P20700 pS23 MCM6 minichromosome maintenance complex component 6 Q14566 pS762 MCM6 minichromosome maintenance complex component 6 Q14566 MDM2 Mdm2, transformed 3T3 cell double minute 2, p53 binding protein (mouse) Q00987 pS166 MDM2 Mdm2, transformed 3T3 cell double minute 2, p53 binding protein (mouse) Q00987 MKI67 antigen identified by monoclonal antibody Ki‐67 P46013 pT181 MKI67 antigen identified by monoclonal antibody Ki‐67 P46013 MKI67 antigen identified by monoclonal antibody Ki‐67 P46013 pT246 MRE11A MRE11 meiotic recombination 11 homolog A (S. -

Sarcomeres Regulate Murine Cardiomyocyte Maturation Through MRTF-SRF Signaling

Sarcomeres regulate murine cardiomyocyte maturation through MRTF-SRF signaling Yuxuan Guoa,1,2,3, Yangpo Caoa,1, Blake D. Jardina,1, Isha Sethia,b, Qing Maa, Behzad Moghadaszadehc, Emily C. Troianoc, Neil Mazumdara, Michael A. Trembleya, Eric M. Smalld, Guo-Cheng Yuanb, Alan H. Beggsc, and William T. Pua,e,2 aDepartment of Cardiology, Boston Children’s Hospital, Boston, MA 02115; bDepartment of Biostatistics and Computational Biology, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, MA 02215; cDivision of Genetics and Genomics, The Manton Center for Orphan Disease Research, Boston Children’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA 02115; dAab Cardiovascular Research Institute, Department of Medicine, University of Rochester School of Medicine and Dentistry, Rochester, NY 14642; and eHarvard Stem Cell Institute, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA 02138 Edited by Janet Rossant, The Gairdner Foundation, Toronto, ON, Canada, and approved November 24, 2020 (received for review May 6, 2020) The paucity of knowledge about cardiomyocyte maturation is a Mechanisms that orchestrate ultrastructural and transcrip- major bottleneck in cardiac regenerative medicine. In develop- tional changes in cardiomyocyte maturation are beginning to ment, cardiomyocyte maturation is characterized by orchestrated emerge. Serum response factor (SRF) is a transcription factor that structural, transcriptional, and functional specializations that occur is essential for cardiomyocyte maturation (3). SRF directly acti- mainly at the perinatal stage. Sarcomeres are the key cytoskeletal vates key genes regulating sarcomere assembly, electrophysiology, structures that regulate the ultrastructural maturation of other and mitochondrial metabolism. This transcriptional regulation organelles, but whether sarcomeres modulate the signal trans- subsequently drives the proper morphogenesis of mature ultra- duction pathways that are essential for cardiomyocyte maturation structural features of myofibrils, T-tubules, and mitochondria.