Misrepresenting Cuba's Punk Rock Trial

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Beyond Salsa Bass the Cuban Timba Revolution

BEYOND SALSA BASS THE CUBAN TIMBA REVOLUTION VOLUME 1 • FOR BEGINNERS FROM CHANGÜÍ TO SON MONTUNO KEVIN MOORE audio and video companion products: www.beyondsalsa.info cover photo: Jiovanni Cofiño’s bass – 2013 – photo by Tom Ehrlich REVISION 1.0 ©2013 BY KEVIN MOORE SANTA CRUZ, CA ALL RIGHTS RESERVED No part of this publication may be reproduced in whole or in part, or stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording or otherwise, without written permission of the author. ISBN‐10: 1482729369 ISBN‐13/EAN‐13: 978‐148279368 H www.beyondsalsa.info H H www.timba.com/users/7H H [email protected] 2 Table of Contents Introduction to the Beyond Salsa Bass Series...................................................................................... 11 Corresponding Bass Tumbaos for Beyond Salsa Piano .................................................................... 12 Introduction to Volume 1..................................................................................................................... 13 What is a bass tumbao? ................................................................................................................... 13 Sidebar: Tumbao Length .................................................................................................................... 1 Difficulty Levels ................................................................................................................................ 14 Fingering.......................................................................................................................................... -

Between Rock and a Hard Place

Rockin' Las Americas The Global Politics of Rock in Latin/o America EDITED BY DEBORAH PACINI HERNANDEZ, HECTOR FERNANDEZ L'HOESTE, AND ERIC ZOLOV University of Pittsburgh Press Published by the University of Pittsburgh Press, Pittsburgh, Pa., 15260 Copyright © 2004, University 01 Pittsburgh Press All rights reserved Manufactured in the United States of America Printed on acid-free paper 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Rockin' las Americas : the global politics of rock in Laing() America / edited by Deborah Pacini Hernandez, Hector Fernandez L'Hoeste, and Eric %ohm p. cut. — (Illuminations) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-8229-4226-7 (cloth : alk. paper) — ISBN 0-8229-5841-4 (pbk. : aik. paper) 1. Rock music—Political aspects—Latin America. 2. Rock tousle— Social aspects—Latin America 1. Pacini Hernandez, Deborah. It. Fernandez Ulloeste, Hector I)., 1962— III. Zolne, Eric. IV. Illuminations (Pittsburgh, Pa.) M1.39I 7.1,27/263 2004 2003027604 Between Rock and a Hard Place Negotiating Rock in Revolutionary Cuba, 1960-1980 DEBORAH PACINI HERNANDEZ AND REEBEE GAROFALO In the mid-1960s, singer/songwriter Silvio Rodriguez was fired from his job at the Cuban Radio and Television Institute for mentioning the Beatles as one of his musical influences on the air. Some thirty-five years later, on De- cember 8, 2000, the anniversary of John Lennon's death, a statue of John Lennon was dedicated in a park located in the once-fashionable Vedado sec- tion of Havana. Present at the ceremony were not only Abel Prieto, Cuba's long-haired Minister of Culture, but Fidel Castro himself, who helped Rodriguez unveil the statue. -

Music Production and Cultural Entrepreneurship in Today’S Havana: Elephants in the Room

MUSIC PRODUCTION AND CULTURAL ENTREPRENEURSHIP IN TODAY’S HAVANA: ELEPHANTS IN THE ROOM by Freddy Monasterio Barsó A thesis submitted to the Department of Cultural Studies In conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Queen’s University Kingston, Ontario, Canada (September, 2018) Copyright ©Freddy Monasterio Barsó, 2018 Abstract Cultural production and entrepreneurship are two major components of today’s global economic system as well as important drivers of social development. Recently, Cuba has introduced substantial reforms to its socialist economic model of central planning in order to face a three-decade crisis triggered by the demise of the USSR. The transition to a new model, known as the “update,” has two main objectives: to make the state sector more efficient by granting more autonomy to its organizations; and to develop alternative economic actors (small private businesses, cooperatives) and self-employment. Cultural production and entrepreneurship have been largely absent from the debates and decentralization policies driving the “update” agenda. This is mainly due to culture’s strategic role in the ideological narrative of the ruling political leadership, aided by a dysfunctional, conservative cultural bureaucracy. The goal of this study is to highlight the potential of cultural production and entrepreneurship for socioeconomic development in the context of neoliberal globalization. While Cuba is attempting to advance an alternative socialist project, its high economic dependency makes the island vulnerable to the forces of global neoliberalism. This study focuses on Havana’s music sector, particularly on the initiatives, musicians and music professionals operating in the informal economy that has emerged as a consequence of major contradictions and legal gaps stemming from an outdated cultural policy and ambiguous regulation. -

Beyoncé, Santana, and Rhythm As a Representation of People and Place and Place Overview

BEYONCÉ, SANTANA, AND RHYTHM AS A REPRESENTATION OF PEOPLE AND PLACE AND PLACE OVERVIEW ESSENTIAL QUESTION How does “the beat” of popular music reflect the histories of multiethnic populations and places? OVERVIEW At different times in American history, rhythm has been a contested issue. Within the cultural “melting pot” of the nation, both the way people feel rhythms and musical meter and the instruments they use to express them have sometimes been interpreted as “dangerous.” During the years in which slavery was a part of American life, the ships that crossed the Atlantic Ocean en route to the Americas, ships carrying African slaves, also brought the music and dance traditions of these people. Many of these traditions were rich with rhythmic complexity. Even today the rhythms we think of as “the beat” in popular music carry traces of the West African music brought to the Americas by slaves, and nearly all of the music we hear now is the result of musical and cultural mixing between the many ethnic populations that have cohabited here since. Music has always been a meeting place, sometimes challenging the “official” systems of social organization. When the slave trade was in practice, each colony and country responded differently to the cultural practices of the forced labor that drove their economies. In Cuba, slaves were permitted to gather at specific times. In these communal moments music and dance traditions from throughout West Africa were both maintained and adapted to their new home. Slaves identified as having musical talent were also required to learn Spanish dance music and perform for plantation owners. -

The Politics and Commodification of Cuban Music During the Special

NEGOTIATION WITH THE REVOLUTION: THE POLITICS AND COMMODIFICATION OF CUBAN MUSIC DURING THE SPECIAL PERIOD by Eric Jason Oberstein Department of Cultural Anthropology Advisors: Caroline Yezer Paul Berliner Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation with distinction for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in the Department of Cultural Anthropology in the Trinity College of Arts and Sciences of Duke University 2007 Acknowledgements I would like to thank Caroline Yezer and Paul Berliner, my committee members, for their constant support and guidance throughout the writing process. They helped me define my topic, read through my drafts, and gave me direction with my ideas. I would like to thank the Department of Cultural Anthropology at Duke University, especially Orin Starn, who encouraged me to write a senior thesis, and Heather Settle, who was one of my first anthropology instructors and who taught me about the depth of Cuba. In addition, I would like to thank Bradley Simmons, my Afro-Cuban percussion mentor, who taught me how to play and appreciate Cuban music. I would also like to thank my family for fostering my passion for Cuban music and culture. A special thanks goes to Osvaldo Medina, my personal Cuban music encyclopedia, who always managed to find me in the corner at family parties and shared stories of Cuban musicians young and old. Finally, I dedicate this thesis to the musicians of Cuba, both on and off the island. Your work forever inspires and moves me. ii Contents Introduction..............................................................................................................................1 Research Question .............................................................................................................1 Significance of Research.................................................................................................. 14 Methods............................................................................................................................ 18 1. -

Redalyc."Somos Cubanos!"

Trans. Revista Transcultural de Música E-ISSN: 1697-0101 [email protected] Sociedad de Etnomusicología España Froelicher, Patrick "Somos Cubanos!" - timba cubana and the construction of national identity in Cuban popular music Trans. Revista Transcultural de Música, núm. 9, diciembre, 2005, p. 0 Sociedad de Etnomusicología Barcelona, España Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=82200903 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Somos Cubanos! Revista Transcultural de Música Transcultural Music Review #9 (2005) ISSN:1697-0101 “Somos Cubanos!“ – timba cubana and the construction of national identity in Cuban popular music Patrick Froelicher Abstract The complex processes that led to the emergence of salsa as an expression of a “Latin” identity for Spanish-speaking people in New York City constitute the background before which the Cuban timba discourse has to be seen. Timba, I argue, is the consequent continuation of the Cuban “anti-salsa-discourse” from the 1980s, which regarded salsa basically as a commercial label for Cuban music played by non-Cuban musicians. I interpret timba as an attempt by Cuban musicians to distinguish themselves from the international Salsa scene. This distinction is aspired by regular references to the contemporary changes in Cuban society after the collapse of the Soviet Union. Thus, the timba is a “child” of the socialist Cuban music landscape as well as a product of the rapidly changing Cuban society of the 1990s. -

Hip-Hop: Authenticity and Rebellion Enrique Del Risco Writer Cuban

Cuban Rap Hip-Hop: Authenticity and Rebellion Enrique del Risco Writer Cuban. Resident of the United States s with so many other things, Cuba is place that will allow this genre to avoid the the last great hope for enthusiasts of contradiction of authenticity and money. At Apure hip-hop in Cuba. It is the genre’s best, they have only a minimal idea of what Promised Land or Jurassic Park. As Sujatha authenticity is, as if a desire to become wealth- Fernandes Cites: “while the distinction ier were less acceptable than just living in between underground and commercial in the poverty and denouncing the situation. In con- United States derives from a perception of sidering vulgar materialism, one might say authenticity and commercial success as oppo- that authenticity’s basic definition stems from a sites, American rappers often accord an line of thinking, or rhetoric, more or less in authenticity or underground status to their keeping with the context in which it exists. For Cuban counterparts, given Cuba’s image as a example, this definition could address the successful revolutionary government among authenticity of a Cuban rapper whose work sections of the African American community.”1 concerns itself more with racism in the United Those who are of that mind seem to be States than in his own country (which was once guided by a much too literal sense of the observed in a U.S. documentary about hip-hop world. Perhaps they believe that if a govern- in Cuba). Even so, one might have to accept ment proclaims itself as revolutionary, it actu- that the aforementioned concern could be con- ally devotes itself to transforming society. -

Sin Título-1

OCT WHAT’S ON 2013 HAVANA ! Praise be to Our Virgen de la Caridad BY Victoria Alcala Just when you think you know Cubans BY Conner Gorry D'DISEGNO. V Festival Leo Havana Guide Respuesta Brouwer de to the Best cubana! Música de Places to eat, Cámara Bars, Clubs Through Sep 24 – Oct 13 & Museums October p 13 p 32 p 49 PRODUCED BY .COM .COM Cuba Absolutely is an independent platform, which seeks to showcase the best in Cuba culture, life-style, sport, travel and much more... we seek to explore Cuba through the eyes of the best writers, photographers and filmmakers, both Cuban and international, who live work, travel and play in Cuba. Beautiful pictures, great videos, opinionated reviews, insightful articles and inside tips. ALL ABOUT CUBA, ALL THE TIME HIGHLIGHTS HAVANA RESTAURANT GUIDE We have reviewed over 150 places to eat in Havana from the coolest new paladar to the old favorites. Check out. The Ultimate Guide to Dining out in Havana. Like us on Facebook for Over 100 videos including Follow us on Twitter for beautiful images, links to interviews with Cuba’s best regular updates of new interesting articles and regular artists, dancers, musicians, content, reviewa, comments updates. writers and directors. and more. OUR CONTRIBUTORS We are deeply indebted and extremely grateful to all of the writers and photograohers who have shared their work with us. We always welcome new contributors and would love hear from you if you have developed a Cuba-related project, idea, photo series or article. You can contact us at [email protected] recommends these Travel Providers for US visitors to Cuba Witness Cuba on routes less traveled. -

Libby Myers Thesis Advisor Ball State University Muncie, Indiana

Combating Bigotry with Beats An Honors Thesis (HONR 499) by Libby Myers Thesis Advisor Dr. Jason Powell Ball State University Muncie, Indiana April2018 Expected Date of Graduation May 2018 sr c_.' \ \) .__}t..r).,.._ ~ '\\-vt-}1 ~ LD 'l)~. ..'f''\ Abstract .--z. &..\ v \\ Dating back 500 years, Cuba has been a country filled with life and culture, yet its people have _t-\tf~ • also struggled for their freedom and right to expression. Historically, music has been a way for Cubans to express their identity as well as their dissatisfaction at social and political situations. More recently, hip hop has played a vital role in the cultural revolution occurring in Cuba from the 1990s to the present, and Cuban artists are laboring against oppression to protest racism and other forms of oppression that are still relevant in Cuban society. My thesis is a playlist of hip hop songs by different Cuban artists that address issues such as racism, racial and cultural identity, women's rights, gender identity, freedom of speech, and the general oppression present in Cuba. Acknowledgements I want to thank my thesis advisor, Jason Powell, for his wonderful support and encouragement throughout the semester, as well as his hard work editing and proofreading all our drafts! I also want to thank Dr. Bell in the Spanish Department for introducing me to music in Cuba and providing me with resources for my thesis. Myers, 1 Process Analysis My thesis is a play list of hip hop music by Cuban artists from the 1990s to the present that addresses the social and political issues of Cuba. -

Redalyc.Making Meaning by Default. Timba and the Challenges Of

Trans. Revista Transcultural de Música E-ISSN: 1697-0101 [email protected] Sociedad de Etnomusicología España Perna, Vincenzo Making meaning by default. Timba and the challenges of escapist music Trans. Revista Transcultural de Música, núm. 9, diciembre, 2005, p. 0 Sociedad de Etnomusicología Barcelona, España Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=82200906 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Making meaning by default. Timba and the challenges of escapist music Revista Transcultural de Música Transcultural Music Review #9 (2005) ISSN:1697-0101 Making meaning by default. Timba and the challenges of escapist music Vincenzo Perna Abstract The article examines timba as a form of discourse inscribed in the influential notion of the ‘black Atlantic’ formulated by Paul Gilroy. It makes the case of timba as a type of non-engaged music which, while presenting itself as emphatically escapist, during the 1990s has in fact become intensely political in the way it has articulated a discourse challenging dominant views on race, class, gender and nation. Significantly, Gilroy’s analysis pays a special attention to music and dance, considering them as foundational elements of black diasporic culture. Such role of music and dance can be seen at work in timba, where they have challenged the conventional -

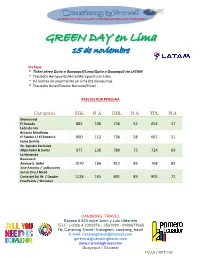

GREEN DAY En Lima

GGRREEEENN DDAAYY eenn LLiimmaa 1155 ddee nnoovviieemmbbrree Incluye: Ticket aéreo Quito o Guayaquil/Lima/Quito o Guayaquil vía LATAM Traslados Aeropuerto/Hotel/Aeropuerto en Lima. 03 noches de alojamiento en Lima (03 desayunos) Traslados Hotel/Estadio Nacional/Hotel PRECIOS POR PERSONA Categoría SGL N.A. DBL N.A. TPL N.A. Monterreal El Ducado 883 106 736 52 654 47 León de oro Britania Miraflores El Tambo I / El Tambo II 900 112 736 58 667 51 Ferré DeVille Sn. Agustin Exclusive Allpa Hotel & Suites 977 136 789 75 724 69 La Hacienda Boulevard Ananay S. Isidro 1070 166 812 83 768 83 Jose Antonio / LyzBussines Sol de Oro / Meliá Costa del Sol W. / Dazzler 1228 165 891 83 805 72 FourPoints / Sheraton CANSIONG TRAVEL Boyacá # 823 entre Junín y Luis Urdaneta TELF: (+593) 4 2302976 - 2561098 - 0999677665 Fb: Cansiong Travel / Instagram: cansiong_travel E-mail: [email protected] [email protected] www.cansiongtravel.com Guayaquil – Ecuador 11/ JUL / 2017 / G2 PRECIOS DE ENTRADAS NETAS NO COMISIONABLES ZONA PRECIO CAMPO $109.00 ORIENTE $ 64.00 LATERAL SUR $ 50.00 LATERAL NORTE $ 50.00 Notas Importantes: Precios no incluyen ningún tipo de gasto especificado en el paquete Tickets aéreos e impuestos de los mismos. Alimentación no mencionada en el programa. Gastos no especificados en el programa ITINERARIO Martes 14 de noviembre 2017 Día 01: Lima Llegada, recepción y traslado al hotel. Tarde libre para actividades de su interés. Alojamiento en Lima. Alimentación: Ninguna Miércoles 15 de noviembre 2017 Día 02: Concierto Green Day A hora coordinada traslado del hotel hacia el Estadio Nacional para disfrutar del gran concierto de Green Day Los Miembros del Salón de la Fama del Rock and Roll y la banda de rock ganadora del Grammy,Green Day anunciaron que traerán su gira Revolution Radio a Latinoamérica. -

From the Political Agenda to the Radio in Santiago De Cuba

Revista de Comunicación Vivat Academia ISSN: 1575-2844 Septiembre 2015 Año XVIII Nº 132 pp 182- 219 INVESTIGACIÓN/RESEARCH Recibido: 05/06/2015 ---Aceptado: 28/07/2015 ---Publicado: 15/09/2015 FROM THE POLITICAL AGENDA TO THE RADIO IN SANTIAGO DE CUBA. A LONGITUDINAL STUDIO OF THEMATIC TRANSFER Viviana Muñiz Zúñiga1: University of Oriente Cuba. [email protected] Rafael Ángel Fonseca Valido: University of Oriente Cuba [email protected] ABSTRACT This piece of research presents a four-time longitudinal analysis of the correlation among the media agenda of the local radio station in Santiago de Cuba, CMKC Radio Revolution, and the political agenda. Its general objective is to determine the extant correlation among the media agenda of the radio station CMKC and the political agenda in Santiago de Cuba in the years 2014 and 2015. The contribution of this piece of research is that is the first of its type in the country, as it explains the relationship between these two agendas in a province during different phases. The studio has been conceived from a quantitative methodology, and methods like Analysis - Synthesis and the Inductive-deductive are used as well as techniques such as Analysis of Content, correlation coefficient by Spearman ranges and participant Observation. With the analysis that was carried out it is demonstrated that there is a moderate, sometimes high relationship between the political agenda and the media agenda under study, and that this characteristic remains stable all through the time the analysis took place. KEY WORDS Political agenda – Media agenda - Correlations - Agenda Setting - Agenda Building.