Indian Derivatives Markets1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

State Authority, Economic Governance and the Politics Of

THE DIVERSITY OF CONVERGENCE: STATE AUTHORITY, ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE AND THE POLITICS OF SECURITIES FINANCE IN CHINA AND INDIA A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Matthew C.J. Rudolph May 2006 © 2006 Matthew C.J. Rudolph THE DIVERSITY OF CONVERGENCE: STATE AUTHORITY, ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE AND THE POLITICS OF SECURITIES FINANCE IN CHINA AND INDIA Matthew C.J. Rudolph, Ph.D. Cornell University 2006 This dissertation explains contrasting patterns of financial reform in China and India. It focuses on “securitization” – the structural shift from credit-based finance (banking) to securities-based finance (stocks and bonds) – as a politically consequential phenomenon in comparative and international political economy. The analysis revises common theories of the developmental state – theories derived from Gerschenkron’s emphasis on directed-credit and the state’s role in capital formation – in light of securitization’s growing global importance in the last twenty years. Contrasting responses to securitization are explained using international and domestic variables including the profile of a country’s exposure to the world economy, the distributional coalition supporting the state and the prevailing structure of property rights. At a theoretical level, the dissertation highlights the political consequences of securitization for state authority in the economy, arguing that directed-credit; 1) enhanced state discretion in the management of distributional coalitions; 2) facilitated the perpetuity of poorly specified property rights; and 3) mitigated the consequences of the country’s position with respect to external trade and investment. Empirically, the research presented here demonstrates that China and India responded differently to the process of securitization, contrary to the expectations of globalization theories that identify finance as a domain in which international forces favoring convergence should be strongest. -

World Bank Document

coz Public Disclosure Authorized oo z L,- QcDN l | C< Public Disclosure Authorized a') z a~~~~~~~~~~~~>Ca) r n -4- s~~~~~~~ Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized CONTEN'TS AND SUMMARY INTERNATIONALLENDING currency debt of four major Chinese banks AND CAPITALMARKETS on review for downgrading. * DEVELOPING-COUNTRY BORROWING PAGE 4 EQUITY PORTFOLIO AND Developing countries raised $20.1 billion in FOREIGN DIRECTINVESTMENT bonds and loans in the fourth quarter of 1994, up slightly over the third quarter. Bond * EMERGINGSTOCK MARKETS PAGE 11 issuance was much higher, but loan volume The IFC's dollar-based composite index was fell. The Mexican peso devaluation and the down 13% in the first quarter, in the wake of weak US dollar threw the markets into tur- the Mexican peso devaluation and the col- moil and caused Latin American bond is- lapse of Barings bank. Latin American mar- suance virtually to dry up. Nevertheless, the kets fell by 28% and Asian by 8%. first quarter saw a number of Korean corpo- Nevertheless, prices recovered strongly to- rate bond issues and a $1 billion project fi- ward the end of the quarter. nancing for a Malaysian toll road. * NEW EQUITIESAND * GLOBALBORROWING PAGE 7 DERIVATIVES PAGE 13 According to the OECD, $274 billion was At $23.3 billion, US investors' net purchases raised in international capital markets in the of international equities in 1994 were only a fourth quarter, bringing the year's total to third of the 1993 figure. Net equity purchases $954 billion, a 17% increase over 1993. New declined sharply throughout 1994 and were syndicated lending remained strong in the -$9 billion in the fourth quarter. -

50. the 2004 Financial System Stability Assessment (FSSA) Attested to the Turnaround in Pakistan’S Banking System (IMF Country Report No

- 32 - References Reinhart, C., K. Rogoff, and M. Savastano, 2003, “Debt Intolerance.” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 1:2003, pp. 1-74. International Monetary Fund, 2003, World Economic Outlook: September 2003—Public Debt in Emerging Markets, (Washington: International Monetary Fund). Manasse, P. and N. Roubini, 2005, “Rules of Thumb for Sovereign Debt Crises”, IMF Working Paper 05/42 (Washington: International Monetary Fund). ©International Monetary Fund. Not for Redistribution - 33 - 15 IV. BANKING SYSTEM AND STOCK MARKET UPDATE A. Introduction 50. The 2004 Financial System Stability Assessment (FSSA) attested to the turnaround in Pakistan’s banking system (IMF Country Report No. 04/215). Seven years of restructuring, recapitalization, and privatization had by mid-2004 transformed the ownership structure, risk management, profitability, and reach of the system, allowing asset quality to improve and credit to expand into previously underserved segments of the economy. Nonetheless, the FSSA cautioned that rapid credit growth “could be problematic if sustained.” 51. This chapter updates some of the FSSA findings and tracks developments over the last 1½ years. Lending activity appears to have approached “boom” thresholds in the period since the FSSA, and the stock market underwent a contained boom-bust cycle in early 2005. Despite this, the banking system has continued to strengthen on an aggregate level, although trends at a few individual banks underscore the need for continued supervisory vigilance. Most financial soundness indicators (FSIs) remain on an improving trajectory. Nevertheless, bank-by-bank stress test results suggest that a few large banks are vulnerable to some shocks. The authorities have continued implementing their financial sector reform agenda and followed-up on FSSA recommendations. -

Revised Carry Forward System (RCFS) 20. in Order to Enhance

Revised Carry Forward System (RCFS) Warehousing 20. In order to enhance liquidity in the capital 21. Warehousing facilitates execution of a large market, a Group set up under the chairmanship firm client order in parts during the same trading of Prof. J.R. Verma reviewed the Revised Carry cycle. SEBI permitted brokers to warehouse trades Forward System (RCFS). The Report of the Group for firm orders of institutional clients. To prevent was submitted in July 1997. The modifications to misuse, certain safeguards like reporting RCFS approved by the regulatory authority include requirements, compulsory delivery of warehouse (a) continuance of the practice of segregating trades, etc. were also introduced. carry forward transactions at the time of execution Clearing Corporation/Settlement Guarantee Fund of trade under the twin track system, (b) a lower 22. Timely completion of settlement contributes daily margin of 10 per cent on carry forward trades to both efficiency and transparency. Failure of any with the proviso that 50 per cent of the daily one member to honour his commitment to the margin would be paid upfront, (c) enhancement exchange on time has cascading effects. All stock of overall carry forward limit to Rs.20 crore per exchanges in the country have therefore been broker and (d) removal of limit of Rs. 10 crore for advised to set up clearing corporation/settlement badla financier. The recommendations made by guarantee fund to ensure timely completion of the Group in regard to strict enforcement of capital settlement. adequacy and related prudential safeguards and monitoring and surveillance system for healthy Securities Lending functioning of the capital market were accepted. -

Badla Financing, Stock Returns and Volatility: the Case Study of Karachi Stock Exchange

Munich Personal RePEc Archive Badla Financing, Stock Returns and Volatility: The Case Study of Karachi Stock Exchange Rashid, Abdul and Ahmad, Shabbir International Institute of Islamic Economics (IIIE)„ International Islamic University, Islamabad, Pakistan 17 January 2008 Online at https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/30487/ MPRA Paper No. 30487, posted 07 Sep 2013 10:50 UTC The Empirical Economics Letters, 7(7): (July 2008) ISSN 1681 8997 Badla Financing, Stock Returns and Volatility: The Case Study of Karachi Stock Exchange Abdul Rashid and Shabbir Ahmad International Institute of Islamic Economics (IIIE), International Islamic University, Islamabad. Email: [email protected] Abstract: Using badla financing as a measure of leverage we examine both temporal and contemporaneous links among badla financing, stock returns and market volatility. We find that the market volatility is significantly and positively related to the change in badla financing and to past market returns. We also observe a significantly positive temporal causation between prior market returns and both badla financing as well as stock price volatility. Keywords: Badla Financing, Stock Returns, Market Volatility, Call Money Rate, Exchange Rate. JEL Classification Number: G10, G14 1. Introduction An understanding of the behavior of financial markets has never been more important than it is today. Following the improvement in technology, many new risk management tools have been introduced that have increased the efficiency of the market. Financial reforms and openness have brought an unbelievable change in the behavior of financial markets and overall stimulated the activities in these markets. Now these markets are more efficient and dynamic/volatile than before. Since forecasting of stock price volatility has many practical applications, there is an increasing interest in modelling the volatilities of stock returns. -

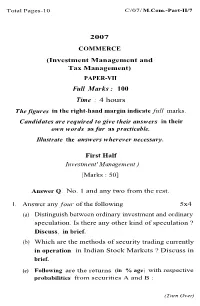

Full Marks : 100 Time : 4 Hours the Figures in the Right-Hand Margin Indicate Full Marks

Total Pages-10 C/07/ M.Com.-Part-II/7 2007 COMMERCE (Investment Management and Tax Management) PAPER-VII Full Marks : 100 Time : 4 hours The figures in the right-hand margin indicate full marks. Candidates are required to give their answers in their own words as far as practicable. Illustrate the answers wherever necessary. First Half Investment' Management ) [Marks : 50] Answer Q. No. 1 and any two from the rest. 1. Answer any four of the following 5x4 (a) Distinguish between ordinary investment and ordinary speculation. Is there any other kind of speculation ? Discuss, in brief. (b) Which are the methods of security trading currently in operation in Indian Stock Markets ? Discuss in brief. (c) Following are the returns (in % age) with respective probabilities from securities A and B : (Turn Over) Using coefficient of variation, which security does appear to be more risky? Security A Security B Return Probability Return Probability (in % age) (in % age) 10 0.30 11 0.20 12 0.40 13 0.30 14 0.30 15 0.30 17 0.20 (d) Following are the returns (in % age) with respective probabilities from securities M and N : Security M Security N Return Probability Return Probability (in % age) (in % age) 9 0.20 8 0.30 11 0.25 10 0.30 13 0.25 12 0.20 15 0.30 14 0.20 Coefficient of correlation of returns between securities M and N is + 0.65. If an investor invests 60% of his investment in security M and balance in the other security, calculate portfolio risk. -

A Case Study of Mumbai and Karachi Stock Exchanges

The Lahore Journal of Economics 11 : 2 (Winter 2006) pp. 79-105 Regulatory Response to Market Volatility and Manipulation: A Case Study of Mumbai and Karachi Stock Exchanges Jamshed Y. Uppal* and Inayat U. Mangla** Abstract This study examines the regulatory intervention in India and Pakistan in response to episodes of excessive market volatility and manipulation and its effectiveness in achieving declared objectives. Our empirical analysis indicates that while the Indian regulatory agencies seem to have achieved their objectives in curtailing manipulative and speculative behavior, there appears to be little impact on such behavior in the case of the Karachi Stock Exchange. Significant differences in the regulatory effectiveness and industry structure may explain the difference in the market behavior outcomes following regulatory interventions. A stronger competitive environment in India, because of the existence of multiple organized exchanges, seems to facilitate effective enforcement of public policy. Key Words: Stock market volatility, manipulation, speculation, scams, corporate governance, regulatory dialectics. Jel Classification: G15, G18, G28, K22, O16 1. Introduction The last two decades have seen unprecedented growth and volatility in the stock markets of developing countries. As emerging markets continue to grow and assume a more prominent role in the economy, the regulatory framework evolves along side, although with delays and sub-optimal solutions, which are characteristic of political processes. Regulatory development takes place, in many cases, as a response to financial crisis, scandals and scams in an effort to restore the investors’ confidence in the markets and institutions. Financial service firms on the other hand indulge * Corresponding Author: Associate Professor of Finance, Department of Business and Economics, Catholic University of America, Washington, D.C. -

Shamshad Akhtar: Pakistan’S Capital Markets – Mobilizing for Growth

Shamshad Akhtar: Pakistan’s capital markets – mobilizing for growth Keynote address by Dr Shamshad Akhtar, Governor of the State Bank of Pakistan, at the Pakistan Capital Markets Conference organized by Pakistan Business Council and IFC, Karachi, 5 September 2006. * * * Good Morning everyone. At the onset I would like to thank Mr. Saleem Raza for inviting me to speak at this conference, and I would also like to acknowledge all the distinguished participants. A lot has been done in Pakistan in terms of financial sector reforms. These reforms have been substantive both in the banking sector as well as in capital markets. We have implemented what you may call the ‘first generation of reforms’ and now we are positioning ourselves for the next ten years. I think there is need to give another jolt to the system and enhance, broaden and deepen the reforms. The first phase has yielded positive results and we are reaping the benefits of that phase. It is in the context of the second generation of reforms that we need to put together all the ideas that come out of international evidence and structure the way forward. This I believe is very important and I hope that today’s forum will give us the opportunity to debate these issues because it’s all about policy choices, and we have to choose a route which is more conducive for Pakistan. Personally I am fascinated and amazed by the changes in the global financial landscape. I think if effectively exploited, these opportunities will augur well for emerging markets in general, and for Pakistan in particular. -

Stock Market Operations

Investment in Shares Dr. S M Shafi Department of Business & Financial Studies University of Kashmir. Synoptic View • Investment Instruments & Avenues • Stock Market • Case for Investing in Shares • Market Index Investment Instruments & Avenues Financial Instruments Two Categories: 1. Money Market Instruments 2. Capital Market Instruments Money Market Instruments 1. Certificate of Deposits 2. Commercial Paper 3. Treasury Bills All maturing within One Year [ Short Term Instruments] Capital Market Instruments 1. Shares 2. Debentures ( Bonds ) S h a r e s 1. Equities ( No Fixed Dividend, Voting Right) 2. Preference Shares ( Dividend Fixed, No Voting Right) [ Maturing after One Year] Debentures: 15% 5000 Debentures of Rs.1000 each Types of Debentures Secured/Unsecured Redeemable/ Convertible/ Zeero Coupon or Naked Irredeemable Non-Convertible Rate/ Specific Debentures Debentures Coupon Rate Investment Options Available To Small Investors Investment Options Remarks • Require huge investment • Land • No stream of regular income • Low risk, highly rewarding. low liquidity • Bank deposits • Low return; low risk & high liquidity • Shares • Regular income plus capital appreciation high • return/risk Bonds • Generate steady regular income • Low return & low risk 8 Stock Market Stock Market Raising of Capital From market: 1. Primary Market [Through IPO] 2. Secondary Market [ Stock Exchange] Why Stock Exchange Market? Two Reasons 1. For exit & Entry Purposes 2. Price Discovery Stock Exchanges • 23 Stock Exchanges in India • BSE & NSE – The most followed -

Financial Derivatives and Banking

Subject: Financial Derivatives Course Code: FM-407 Author: Dr. Sanjay Tiwari Lesson No.: 1 Vetter: Prof. M.S. Turan INTRODUCTION TO DERIVATIVE SECURITIES Structure 1.0 Objectives 1.1 Introduction 1.2 Defining derivatives 1.3 Evolution of derivatives 1.4 Features of financial derivatives 1.5 Types of financial derivatives 1.6 Uses and functions of derivatives 1.6.1 Uses of derivatives 1.6.2 Functions of derivatives 1.7 Futures contract 1.8 Features of financial futures contract 1.9 Types of financial futures contract 1.10 Forward contract 1.11 Features of forward contract 1.12 Types of forward contract 1.13 Distinction between futures and forward contract 1.14 Summary 1.15 Key words 1.16 Self assessment questions 1.17 Reference/suggested readings 1.0 Objectives After going through this lesson you will be able to: • understand meaning and evolution of derivatives 1 • describe the features and types of financial derivatives • understand uses and functions of derivative securities • distinguish between futures and forward contracts 1.1 Introduction The objective of an investment decision is to get required rate of return with minimum risk. To achieve this objective, various instruments, practices and strategies have been devised and developed in the recent past. With the opening of boundaries for international trade and business, the world trade gained momentum in the last decade, the world has entered into a new phase of global integration and liberalisation. The integration of capital markets world-wide has given rise to increased financial risk with the frequent changes in the interest rates, currency exchange rate and stock prices. -

A Study of Foreign Institutional Investors' (FII) Investment in Indian Equity Market

A study of Foreign Institutional Investors' (FII) Investment in Indian Equity Market A Synopsis submitted to Gujarat Technological University for the Award of Doctor of Philosophy in Management by JOSHI MRUNAL CHETANBHAI Enrollment No. 139997292006 under supervision of Dr. Jayesh N. Desai GUJARAT TECHNOLOGICAL UNIVERSITY AHMEDABAD [March – 2019] 1 Title of the thesis A study of Foreign Institutional Investors' (FII) Investment in Indian Equity Market Abstract Economic development is essential for all the countries, especially for the developing countries / emerging economies. As economic development provides solution to many problems viz. related to unemployment, poverty, providing basic necessity of people of developing countries, increasing national output ect. It also helps in improving quality of life and wellbeing of people over there. Economic development depends up on production function of Land, Labour and Capital. Any of the country can not make changes in their existing land available to them easily as well as population (labour) can not be immediately (in short-term) change in its demography. But capital can be raised at faster rate and can be used in developing labour as well as to exploit use of other resources optimally. Foreign investment is one of the important good source of raising capital, but there is a hazard of covenants and controls of lending countries. But if such resources are utilized properly, pace of economy’s growth rate can be accelerated. Like other counties FDI and FII are sources of such foreign capital in India. In India, SEBI and RBI are important regulatory bodies concerning to foreign capital. SEBI regulates mainly entry and operations of FII in Indian capital market. -

PNACC467.Pdf

I I I I Report on Stock Inde\. Futures for the I ~atIOnal Stock Exchange of IndIa Ltd I US Agency for InternatIOnal Development Contract #386-0531-C-00-5010-00 I Project #386-0531-3-30069 Januarv 19, 1998 I I I I I I I I I PrIce Waterhouse LLP 1616 North Fort Meyer Drne Rosslyn, VA 22209 I USA Tel (703) 741-1000 I Fax (703) 741-1616 I I Financial Institutions Reforms 128 TV Ind ustnal Estate Telephone 4946630 4963599 I and Expansion (FIRE) Project Worll Mumbal 400 025 Fax (91 22) 4963555 I I Price Waterhouse LLP January 19, 1998 • I Dr RH PatIl Managmg Duector NatIOnal Stock E"'Cchange ofIndia Ltd I Mahmdra Towers, A Wmg, 1st Floor RBC, Worll I Murnbm 400 018 Subject Report on Stock Index Futures at the NatIOnal Stock Exchange ofIndia Ltd I Dear Dr PatIl Pnce Waterhouse LLP (PW), under the USAID FmancIaI InstitutIOns Reform and ExpansIOn I (FIRE) proJect, arranged for Mr MIchael Gorham to spend time With the NatIOnal Stock E"'Cchange (NSE) denvatIVes staffdurmg the month ofOctober 1997 Mr Gorham was VIce I PreSIdent ofInternatIOnal Market Development at the ChIcago Mercantile E"'Cchange (CME) where he worked for 18 years I The attached report contams 1 A analysIs entitled "Does India Really Need Stock Inde'\. Futures IfIt Has BadIa?" I WhICh compares the role ofbadla versus the role ofmdex denvatIVes, 2 A IeVIew ofNSE's preparedness for tradmg stock mdex futures, mcludmg a reVIew I ofthe regulatIOns for the new denvatIves dIvlSlon as gIVen to hIm m October 1997, and I 3 A summary ofthe workshops Mr Gorham gave whIle reSIdent at the NSE