Inflammatory Bowel Agents Class Update

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List of Covered Drugs

List of Covered Drugs Effective July 1, 2016 INTRODUCTION We are pleased to provide the 2011 Gold Coast Health Plan List of Covered Drugs as a useful reference and informational tool. The GCHP List of Covered Drugs can assist practitioners in selecting clinically appropriate and cost effective products for their patients. The information contained in the GCHP List of Covered Drugs is provided solely for the convenience of medical providers. We do not warrant or assure accuracy of such information nor is it intended to be comprehensive in nature. This List of Covered Drugs is not intended to be a substitute for the knowledge, expertise, skill and judgment of the medical provider in his or her choice of prescription drugs. All the information in this List of Covered Drugs is provided as a reference for drug therapy selection. Specific drug selection for an individual patient rests solely with the prescriber. We assume no responsibility for the actions or omissions of any medical provider based upon reliance, in whole or in part, on the information contained herein. The medical provider should consult the drug manufacturer's product literature or standard references for more detailed information. National guidelines can be found on the National Guideline Clearinghouse site at http://www.guideline.gov PREFACE The GCHP List of Covered Drugs is organized by sections. Each section is divided by therapeutic drug class primarily defined by mechanism of action. Unless exceptions are noted, generally all applicable dosage forms and strengths of the drug cited are included in the GCHP List of Covered Drugs. Generics should be considered the first line of prescribing. -

Inflammatory Bowel Disease Irritable Bowel Syndrome

Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Irritable Bowel Syndrome Similarities and Differences 2 www.ccfa.org IBD Help Center: 888.MY.GUT.PAIN 888.694.8872 Important Differences Between IBD and IBS Many diseases and conditions can affect the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, which is part of the digestive system and includes the esophagus, stomach, small intestine and large intestine. These diseases and conditions include inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). IBD Help Center: 888.MY.GUT.PAIN 888.694.8872 www.ccfa.org 3 Inflammatory bowel diseases are a group of inflammatory conditions in which the body’s own immune system attacks parts of the digestive system. Inflammatory Bowel Disease Inflammatory bowel diseases are a group of inflamma- Causes tory conditions in which the body’s own immune system attacks parts of the digestive system. The two most com- The exact cause of IBD remains unknown. Researchers mon inflammatory bowel diseases are Crohn’s disease believe that a combination of four factors lead to IBD: a (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC). IBD affects as many as 1.4 genetic component, an environmental trigger, an imbal- million Americans, most of whom are diagnosed before ance of intestinal bacteria and an inappropriate reaction age 35. There is no cure for IBD but there are treatments to from the immune system. Immune cells normally protect reduce and control the symptoms of the disease. the body from infection, but in people with IBD, the immune system mistakes harmless substances in the CD and UC cause chronic inflammation of the GI tract. CD intestine for foreign substances and launches an attack, can affect any part of the GI tract, but frequently affects the resulting in inflammation. -

Crohn's & Colitis Program, Patient Information Guide

Inflammatory Bowel Disease Program Patient Information Guide Page # Contents ..........................................................................................................................................1 Welcome! Welcome Letter ....................................................................................................................3 Important Things to Know Up Front ....................................................................................4 Meet Your Crohn’s & Colitis Team .....................................................................................6 How to Contact Us Crohn’s & Colitis Clinic Schedule .....................................................................................11 Physician and Nurse Contact Information..........................................................................12 Appointment Scheduling and Other Contact Information..................................................13 The Basics of Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) Basic Information about Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) ...........................................14 Frequently Asked Questions about Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) ..........................18 Testing in IBD Colonoscopy and Flexible Sigmoidoscopy ........................................................................20 Upper Endoscopy ...............................................................................................................21 Capsule Endoscopy and Deep Enteroscopy .......................................................................22 -

Inflammatory Bowel Disease Agents

Therapeutic Class Overview Inflammatory Bowel Disease Agents INTRODUCTION • Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a spectrum of chronic idiopathic inflammatory intestinal conditions that cause gastrointestinal symptoms including diarrhea, abdominal pain, bleeding, fatigue, and weight loss. The exact cause of IBD is unknown; however, proposed etiologies involve a combination of infectious, genetic, and lifestyle factors (Bernstein et al 2015, Peppercorn 2019[a], Peppercorn 2020[c]). • Complications of IBD include hemorrhage, rectal fissures, fistulas, peri-rectal and intra-abdominal abscesses, and colon cancer. Possible extra-intestinal complications include hepatobiliary complications, anemia, arthritis and arthralgias, uveitis, skin lesions, and mood and anxiety disorders (Bernstein et al 2015). • Ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn’s disease (CD) are 2 forms of IBD that differ in pathophysiology and presentation; as a result of these differences, the approach to the treatment of each condition often differs (Peppercorn 2019[a]). • UC is characterized by recurrent episodes of inflammation of the mucosal layer of the colon. The inflammation, limited to the mucosa, commonly involves the rectum and may extend in a proximal and continuous fashion to affect other parts of the colon. The hallmark clinical symptom is an inflamed rectum with symptoms of urgency, bleeding, and tenesmus (Peppercorn 2020[c], Rubin et al 2019). • CD can involve any part of the gastrointestinal tract and is characterized by transmural inflammation and “skip areas.” Transmural inflammation may lead to fibrosis, strictures, sinus tracts, and fistulae (Peppercorn 2019[b]). • The immune system is known to play a critical role in the underlying pathogenesis of IBD. It is suggested that abnormal responses of both innate and adaptive immunity mechanisms induce aberrant intestinal tract inflammation in IBD patients (Geremia et al 2014). -

Prediction of Premature Termination Codon Suppressing Compounds for Treatment of Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy Using Machine Learning

Prediction of Premature Termination Codon Suppressing Compounds for Treatment of Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy using Machine Learning Kate Wang et al. Supplemental Table S1. Drugs selected by Pharmacophore-based, ML-based and DL- based search in the FDA-approved drugs database Pharmacophore WEKA TF 1-Palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3- 5-O-phosphono-alpha-D- (phospho-rac-(1-glycerol)) ribofuranosyl diphosphate Acarbose Amikacin Acetylcarnitine Acetarsol Arbutamine Acetylcholine Adenosine Aldehydo-N-Acetyl-D- Benserazide Acyclovir Glucosamine Bisoprolol Adefovir dipivoxil Alendronic acid Brivudine Alfentanil Alginic acid Cefamandole Alitretinoin alpha-Arbutin Cefdinir Azithromycin Amikacin Cefixime Balsalazide Amiloride Cefonicid Bethanechol Arbutin Ceforanide Bicalutamide Ascorbic acid calcium salt Cefotetan Calcium glubionate Auranofin Ceftibuten Cangrelor Azacitidine Ceftolozane Capecitabine Benserazide Cerivastatin Carbamoylcholine Besifloxacin Chlortetracycline Carisoprodol beta-L-fructofuranose Cilastatin Chlorobutanol Bictegravir Citicoline Cidofovir Bismuth subgallate Cladribine Clodronic acid Bleomycin Clarithromycin Colistimethate Bortezomib Clindamycin Cyclandelate Bromotheophylline Clofarabine Dexpanthenol Calcium threonate Cromoglicic acid Edoxudine Capecitabine Demeclocycline Elbasvir Capreomycin Diaminopropanol tetraacetic acid Erdosteine Carbidopa Diazolidinylurea Ethchlorvynol Carbocisteine Dibekacin Ethinamate Carboplatin Dinoprostone Famotidine Cefotetan Dipyridamole Fidaxomicin Chlormerodrin Doripenem Flavin adenine dinucleotide -

The Efficacy of Probiotics, Prebiotic Inulin-Type Fructans, and Synbiotics in Human Ulcerative Colitis: a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Supplementary Materials and Data of Review: The Efficacy of Probiotics, Prebiotic Inulin-Type Fructans, and Synbiotics in Human Ulcerative Colitis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Supplementary Data S1 Search strategy Only clinical trial publications and human filters were used in the literature search performed in PUBMED. The studies were searched using the terms “ulcerative colitis” in combination with “probiotic”, “synbiotic”, and “inflammatory bowel disease” in combination with “prebiotic”, “inulin”, “FOS” and “fructo-oligosaccharides”. The search in SCOPUS was performed using combinations of the terms “ulcerative colitis” AND “inulin” limited to document types “Article”. Another search used “ulcerative colitis” AND “probiotic” AND “human” limited to document type “Article” and the subareas “Medicine”, “Immunology and Microbiology” and “Health Professions” and the exact key words “Controlled Study”, “Clinical Article”, “Clinical Trials”, “Controlled Clinical Trial” and “Double-Blind Method”. An additional search using the combinations “ulcerative colitis” AND “synbiotic” AND “human” limited to document type “Article” and excluding the exact key word “Crohn Disease”. In all cases, the search was limited to the languages “Spanish” and “English” Supplementary Table S1 Risk of bias of selected studies and and data data bias bias of generation generation assessment) reporting outcome concealment sources (participants personnel) personnel) Sequence (outcome Selective Other Allocation Incomplete Blinding Random Blinding Matsuoka et al. 2018 ? + + + + + + Tamaki et al. 2016 ? + + ? - ? + Yoshimatsu et al. 2015 ? ? + ? - + + Petersen et al. 2014 ? + + ? + + + Groeger et al. 2013 - - + ? - ? + Oliva et al. 2012 + + + ? - + + Wildt et al. 2011 ? + + ? + + + Tursi et al. 2010 ? + + ? + ? + Matthes et al. 2010 ? + + ? - + + Ng et al. 2010 ? - + ? + ? + Sood et al. 2009 + + + ? - ? + Miele et al. 2009 + + + ? - ? + Furrie et al. -

Stems for Nonproprietary Drug Names

USAN STEM LIST STEM DEFINITION EXAMPLES -abine (see -arabine, -citabine) -ac anti-inflammatory agents (acetic acid derivatives) bromfenac dexpemedolac -acetam (see -racetam) -adol or analgesics (mixed opiate receptor agonists/ tazadolene -adol- antagonists) spiradolene levonantradol -adox antibacterials (quinoline dioxide derivatives) carbadox -afenone antiarrhythmics (propafenone derivatives) alprafenone diprafenonex -afil PDE5 inhibitors tadalafil -aj- antiarrhythmics (ajmaline derivatives) lorajmine -aldrate antacid aluminum salts magaldrate -algron alpha1 - and alpha2 - adrenoreceptor agonists dabuzalgron -alol combined alpha and beta blockers labetalol medroxalol -amidis antimyloidotics tafamidis -amivir (see -vir) -ampa ionotropic non-NMDA glutamate receptors (AMPA and/or KA receptors) subgroup: -ampanel antagonists becampanel -ampator modulators forampator -anib angiogenesis inhibitors pegaptanib cediranib 1 subgroup: -siranib siRNA bevasiranib -andr- androgens nandrolone -anserin serotonin 5-HT2 receptor antagonists altanserin tropanserin adatanserin -antel anthelmintics (undefined group) carbantel subgroup: -quantel 2-deoxoparaherquamide A derivatives derquantel -antrone antineoplastics; anthraquinone derivatives pixantrone -apsel P-selectin antagonists torapsel -arabine antineoplastics (arabinofuranosyl derivatives) fazarabine fludarabine aril-, -aril, -aril- antiviral (arildone derivatives) pleconaril arildone fosarilate -arit antirheumatics (lobenzarit type) lobenzarit clobuzarit -arol anticoagulants (dicumarol type) dicumarol -

National Quality Forum

NQF #PSM-030-10 NATIONAL QUALITY FORUM Measure Evaluation 4.1 January 2010 This form contains the measure information submitted by stewards. Blank fields indicate no information was provided. Attachments also may have been submitted and are provided to reviewers. The sub-criteria and most of the footnotes from the evaluation criteria are provided in Word comments and will appear if your cursor is over the highlighted area (or in the margin if your Word program is set to show revisions in balloons). Hyperlinks to the evaluation criteria and ratings are provided in each section. TAP/Workgroup (if utilized): Complete all yellow highlighted areas of the form. Evaluate the extent to which each sub-criterion is met. Based on your evaluation, summarize the strengths and weaknesses in each section. Note: If there is no TAP or workgroup, the SC also evaluates the sub-criteria (yellow highlighted areas). Steering Committee: Complete all pink highlighted areas of the form. Review the workgroup/TAP assessment of the sub-criterion, noting any areas of disagreement; then evaluate the extent to which each major criterion is met; and finally, indicate your recommendation for the endorsement. Provide the rationale for your ratings. Evaluation ratings of the extent to which the criteria are met C = Completely (unquestionably demonstrated to meet the criterion) P = Partially (demonstrated to partially meet the criterion) M = Minimally (addressed BUT demonstrated to only minimally meet the criterion) N = Not at all (NOT addressed; OR incorrectly addressed; OR demonstrated to NOT meet the criterion) NA = Not applicable (only an option for a few sub-criteria as indicated) (for NQF staff use) NQF Review #: PSM-030-10 NQF Project: Patient Safety Measures MEASURE DESCRIPTIVE INFORMATION De.1 Measure Title: Patient(s) with inflammatory bowel disease taking methotrexate, sulfasalazine, mercaptopurine, or azathioprine that had a CBC in last 3 reported months. -

Olsalazine Is Not Superior to Placebo in Maintaining Remission Of

552 Gut 2001;49:552–556 Olsalazine is not superior to placebo in maintaining remission of inactive Crohn’s colitis Gut: first published as 10.1136/gut.49.4.552 on 1 October 2001. Downloaded from and ileocolitis: a double blind, parallel, randomised, multicentre study N Mahmud, M A Kamm, J L Dupas, D P Jewell, C A O’Morain, D G Weir, D Kelleher Abstract their participation in the trial than those Background and aims—The benefit of taking placebo. This diVerence was not 5-aminosalicylic acid therapy for mainte- related to relapse of disease, as measured nance of remission in Crohn’s disease is by CDAI and clinical measures, but rather controversial. The primary aim of this was due to the development of intolerable study was to evaluate the prophylactic adverse medical events of a non-serious properties of olsalazine in comparison nature related to the gastrointestinal with placebo for maintenance of remis- tract. The gastrointestinal related events sion in quiescent Crohn’s colitis and/or in the olsalazine treated group may be due ileocolitis. to the diVerence in gastrointestinal status Methods—In this randomised, double at baseline which favoured the placebo blind, parallel group study of olsalazine treatment group. versus placebo, 328 patients with quiescent (Gut 2001;49:552–556) Crohn’s colitis and/or ileocolitis were re- cruited. Treatment consisted of olsalazine Keywords: olsalazine; Crohn’s disease; colitis; ileocolitis 2.0 g daily or placebo for 52 weeks. The pri- mary end point of eYcacy was relapse, as Department of Clinical defined by the Crohn’s disease activity Sulphasalazine has been in use for almost four Medicine, Trinity index (CDAI) and by clinical relapse. -

Influence of Olsalazine on Gastrointestinal Transit in Ulcerative Colitis

Gut: first published as 10.1136/gut.28.11.1474 on 1 November 1987. Downloaded from Glit, 1987, 28, 1474- 1477 Influence of olsalazine on gastrointestinal transit in ulcerative colitis S S C RAO, N W READ, AND C D IIOLDSWORTII Froom t1e Gastrointestisnal Uniit, Royal Hall(tishlire Hospital, .Slljfie ll SUMMARY The effect of olsalazine on stool output and the transit of a solid radiolabelled meal through the stomach, small intestine and colon was studied in six patients with ulcerative colitis intolerant of sulphasalazine. Olsalazine 250 mg four times daily significantly accelerated gastric emptying (mean±SD; 45-3±24-2 min v 67-3±33-1 min, p<)-05), mouth to caecum transit time (242±41 min i, 325+33 min, p<()-()2) and whole gut transit time (6(05±26 h v 37-8±17-8 h, p<()-()5). No significant changes were seen in mean daily stool weight (215±41 g v 162±62 g) and mean daily stool frequency (2-2±()-6 v 2-4±1-8). None of these patients developed diarrhoea, but acceleration of gastric and intestinal transit m'ay be responsible for the diarrhoea reported in some patients taking this drug. Sulphalsala.zine (SASP) conisists of 5-arminosalicylic ulcerative colitis all of whom were intolerant of acid (5-ASA) and sulphapyridine linked together by SASP. The clinical detaills of the patients and the http://gut.bmj.com/ ain a(zo bond. 5-ASA has ilOW beenl conlfirimled as the adverse effects previously experienced with SASP beneticial moiety of SASP for the treatment of are shown in Table 1. -

PRODUCT MONOGRAPH DIPENTUM ® (Olsalazine Sodium)

PRODUCT MONOGRAPH DIPENTUM ® (olsalazine sodium) 250 mg Capsules Lower gastrointestinal anti-inflammatory Atnahs Pharma UK Limited Date of Preparation: Sovereign House March 13, 2015 Miles Gray Road Basildon Essex SS14 3FR United Kingdom Distributed by: Searchlight Pharma Inc. Montreal, Quebec, H3J 1M1. Control # 182519 ® DIPENTUM is a registered trademark of Atnahs Pharma UK Limited NAME OF DRUG Dipentum (olsalazine sodium) THERAPEUTIC CLASSIFICATION Lower gastrointestinal anti-inflammatory ACTION AND CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY The conversion of olsalazine to 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA) in the colon is similar to that of sulfasalazine (SASP), which is converted into sulfapyridine and 5-ASA. On a weight basis olsalazine delivers twice the amount of 5-ASA to the colon compared with SASP and there is no residual carrier molecule (sulfapyridine) following olsalazine administration. It is thought that the 5-ASA component is therapeutically active in ulcerative colitis. The usual dose of sulfasalazine for maintenance of remission in patients with ulcerative colitis is 2 grams daily, which would provide approximately 0.8 gram of mesalamine to the colon. More than 0.9 gram of mesalamine would usually be made available in the colon from 1 gram of olsalazine. The mechanism of action of 5-ASA (and SASP) is unknown, but appears to be topical rather than systemic. Mucosal production of arachidonic acid (AA) metabolites, both through the cyclooxygenase pathways (i. e., prostanoids), and through the lipoxygenase pathways (i. e., leukotrienes (LTs) and hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acids [HETEs]) is increased in patients with chronic inflammatory bowel disease, and it is possible that mesalamine diminishes inflammation by blocking cyclooxygenase and inhibiting prostaglandin (PG) production in the colon. -

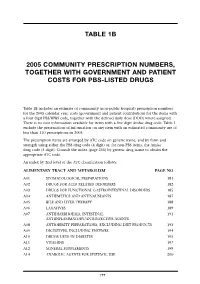

Table 1B 2005 Community Prescription Numbers, Together with Government

TABLE 1B 2005 COMMUNITY PRESCRIPTION NUMBERS, TOGETHER WITH GOVERNMENT AND PATIENT COSTS FOR PBS-LISTED DRUGS Table 1B includes an estimate of community (non-public hospital) prescription numbers for the 2005 calendar year, costs (government and patient contribution) for the items with a four digit PBS/RPBS code, together with the defined daily dose (DDD) where assigned. There is no cost information available for items with a five digit Amfac drug code. Table 1 exclude the presentation of information on any item with an estimated community use of less than 110 prescriptions in 2005. The prescription items are arranged by ATC code on generic name, and by form and strength using either the PBS drug code (4 digit) or, for non-PBS items, the Amfac drug code (5 digit). Consult the index (page 255) by generic drug name to obtain the appropriate ATC code. An index by 2nd level of the ATC classification follows: ALIMENTARY TRACT AND METABOLISM PAGE NO A01 STOMATOLOGICAL PREPARATIONS 181 A02 DRUGS FOR ACID RELATED DISORDERS 182 A03 DRUGS FOR FUNCTIONAL GASTROINTESTINAL DISORDERS 185 A04 ANTIEMETICS AND ANTINAUSEANTS 187 A05 BILE AND LIVER THERAPY 188 A06 LAXATIVES 189 A07 ANTIDIARRHOEALS, INTESTINAL 191 ANTIINFLAMMATORY/ANTIINFECTIVE AGENTS A08 ANTIOBESITY PREPARATIONS, EXCLUDING DIET PRODUCTS 193 A09 DIGESTIVES, INCLUDING ENZYMES 194 A10 DRUGS USED IN DIABETES 195 A11 VITAMINS 197 A12 MINERAL SUPPLEMENTS 199 A14 ANABOLIC AGENTS FOR SYSTEMIC USE 200 177 BLOOD AND BLOOD FORMING ORGANS B01 ANTITHROMBOTIC AGENTS 201 B02 ANTIHAEMORRHAGICS 203 B03