Early Dynastic Temples, a Quantitative Approach to the Bent-Axis Shrines

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download PDF Version of Article

STUDIA ORIENTALIA PUBLISHED BY THE FINNISH ORIENTAL SOCIETY 106 OF GOD(S), TREES, KINGS, AND SCHOLARS Neo-Assyrian and Related Studies in Honour of Simo Parpola Edited by Mikko Luukko, Saana Svärd and Raija Mattila HELSINKI 2009 OF GOD(S), TREES, KINGS AND SCHOLARS clay or on a writing board and the other probably in Aramaic onleather in andtheotherprobably clay oronawritingboard ME FRONTISPIECE 118882. Assyrian officialandtwoscribes;oneiswritingincuneiformo . n COURTESY TRUSTEES OF T H E BRITIS H MUSEUM STUDIA ORIENTALIA PUBLISHED BY THE FINNISH ORIENTAL SOCIETY Vol. 106 OF GOD(S), TREES, KINGS, AND SCHOLARS Neo-Assyrian and Related Studies in Honour of Simo Parpola Edited by Mikko Luukko, Saana Svärd and Raija Mattila Helsinki 2009 Of God(s), Trees, Kings, and Scholars: Neo-Assyrian and Related Studies in Honour of Simo Parpola Studia Orientalia, Vol. 106. 2009. Copyright © 2009 by the Finnish Oriental Society, Societas Orientalis Fennica, c/o Institute for Asian and African Studies P.O.Box 59 (Unioninkatu 38 B) FIN-00014 University of Helsinki F i n l a n d Editorial Board Lotta Aunio (African Studies) Jaakko Hämeen-Anttila (Arabic and Islamic Studies) Tapani Harviainen (Semitic Studies) Arvi Hurskainen (African Studies) Juha Janhunen (Altaic and East Asian Studies) Hannu Juusola (Semitic Studies) Klaus Karttunen (South Asian Studies) Kaj Öhrnberg (Librarian of the Society) Heikki Palva (Arabic Linguistics) Asko Parpola (South Asian Studies) Simo Parpola (Assyriology) Rein Raud (Japanese Studies) Saana Svärd (Secretary of the Society) -

Republic of Iraq

Republic of Iraq Babylon Nomination Dossier for Inscription of the Property on the World Heritage List January 2018 stnel oC fobalbaT Executive Summary .......................................................................................................................... 1 State Party .......................................................................................................................................................... 1 Province ............................................................................................................................................................. 1 Name of property ............................................................................................................................................... 1 Geographical coordinates to the nearest second ................................................................................................. 1 Center ................................................................................................................................................................ 1 N 32° 32’ 31.09”, E 44° 25’ 15.00” ..................................................................................................................... 1 Textural description of the boundary .................................................................................................................. 1 Criteria under which the property is nominated .................................................................................................. 4 Draft statement -

Early Uruk Expansion in Iraqi Kurdistan: New Data from Girdi Qala and Logardan Regis Vallet

Early Uruk Expansion in Iraqi Kurdistan: New Data from Girdi Qala and Logardan Regis Vallet To cite this version: Regis Vallet. Early Uruk Expansion in Iraqi Kurdistan: New Data from Girdi Qala and Logardan. Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East, 2018, Munich, Germany. hal-03088149 HAL Id: hal-03088149 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03088149 Submitted on 2 Jan 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. 445 Early Uruk Expansion in Iraqi Kurdistan: New Data from Girdi Qala and Logardan Régis Vallet 1 Abstract Until very recently, the accepted idea was that the Uruk expansion began during the north- Mesopotamian LC3 period, with a first phase characterized by het presence of BRBs and other sporadic traces in local assemblages. Excavations at Girdi Qala and Logardan in Iraqi Kurdistan, west of the Qara Dagh range in ChamchamalDistrict (Sulaymaniyah Governorate) instead offer clear evidence for a massive and earlyUruk presence with mo- numental buildings, ramps, gates, residential and craft areasfrom the very beginning of the 4th millennium BC. Excavation on the sites of Girdi Qala and Logardan started in15. -

Neo Babylonian Rule

Neo Babylonians Rule “The Most Accomplished Empire” *Clears throat* Thank you. Thank you ever so much distinguished colleagues and professors for inviting me to speak to you today. As many of you know I'm professor Olivia Eichman of archeological studies at Stanford University. I have also worked at various dig sites in ancient sumers regions. All of these excavations lead me to countless degrees in antiquity. Enough about me already, I'm here to talk to you about about the great Mesopotamian Empires. But which empire was the greatest? Was it the Akkadians with the first empire? Or the Assyrians who reigned the longest? Neither of these empires strike me as the most accomplished. The Neo Babylonian’s Empire was the most accomplished empire by far and when you leave this room today I guarantee you will think as highly of them as I do too. Why do I think that the Neo Babylonians are the most accomplished? For starters, their ruler knew how to keep his empire safe. He had many safety precautions. One way Nebuchadrezzar II insured safety among his people was by surrounding their city in a wall so great in size two chariots could ride on it side by side. But that isn't all. No. Nebuchadnezzar II built another wall inside of the other wall for added protection. Both walls were named after Mesopotamian gods and goddesses. One of the gates that was built was called Ishtar gate, named after the goddess of war and love. To top it all off the walls were surrounded by a moat. -

Crossroads 360 Virtual Tour Script Edited

Crossroads of Civilization Virtual Tour Script Note: Highlighted text signifies content that is only accessible on the 360 Tour. Welcome to Crossroads of Civilization. We divided this exhibit not by time or culture, but rather by traits that are shared by all civilizations. Watch this video to learn more about the making of Crossroads and its themes. Entrance Crossroads of Civilization: Ancient Worlds of the Near East and Mediterranean Crossroads of Civilization looks at the world's earliest major societies. Beginning more than 5,000 years ago in Egypt and the Near East, the exhibit traces their developments, offshoots, and spread over nearly four millennia. Interactive timelines and a large-scale digital map highlight the ebb and flow of ancient cultures, from Egypt and the earliest Mesopotamian kingdoms of the Akkadians, Babylonians, and Assyrians, to the vast Persian, Hellenistic, and finally Roman empires, the latter eventually encompassing the entire Mediterranean region. Against this backdrop of momentous historical change, items from the Museum's collections are showcased within broad themes. Popular elements from classic exhibits of former years, such as our Greek hoplite warrior and Egyptian temple model, stand alongside newly created life-size figures, including a recreation of King Tut in his chariot. The latest research on our two Egyptian mummies features forensic reconstructions of the individuals in life. This truly was a "crossroads" of cultural interaction, where Asian, African, and European peoples came together in a massive blending of ideas and technologies. Special thanks to the following for their expertise: ● Dr. Jonathan Elias - Historical and maps research, CT interpretation ● Dr. -

The Origins of Social Justice in the Ancient Mesopotamian Religious Traditions Brian R

Digital Commons @ George Fox University Faculty Publications - College of Christian Studies College of Christian Studies 4-2006 The Origins of Social Justice in the Ancient Mesopotamian Religious Traditions Brian R. Doak George Fox University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/ccs Part of the Near Eastern Languages and Societies Commons, and the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Doak, Brian R., "The Origins of Social Justice in the Ancient Mesopotamian Religious Traditions" (2006). Faculty Publications - College of Christian Studies. Paper 185. http://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/ccs/185 This Conference Proceeding is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Christian Studies at Digital Commons @ George Fox University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications - College of Christian Studies by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ George Fox University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “The Origins of Social Justice in the Ancient Mesopotamian Religious Traditions” Brian R. Doak Presented at the American Schools of Oriental Research Central States Meeting St. Louis, MO (April 2006) Note: This paper was solicited from me as an entry in an introductory multi-volume encyclopedia project on social justice in the world’s religious traditions. I presented it, polished it up for publication, and then the whole project fell apart for some reason that I never understood a few months after I submitted the piece. Since it will never see the light of day otherwise, I post it here for whomever might find it useful. (I) Introduction The existence of written law in the ancient Near East predates the earliest legal codes of other notable ancient civilizations, including those in China and India; thus, through the early Mesopotamians, we are given the first actual historical glimpse of law as idealized and, in some cases, practiced in human civilization. -

12. White Temple and Its Ziggurat Uruk (Modern Warka, Iraq). Sumerian. C. 3500 – 3000 B.C.E. Mud Brick. (2 Images) • Article

12. White Temple and its ziggurat Uruk (modern Warka, Iraq). Sumerian. C. 3500 – 3000 B.C.E. Mud brick. (2 images) Article at Khan Academy dedicated to the sky god Anu, this temple would have towered well above (approximately 40 feet) the flat plain of Uruk, and been visible from a great distance—even over the defensive walls of the city where city life began more than five thousand years ago and where the first writing emerged—was clearly one of the most important places in southern Mesopotamia A ziggurat is a built raised platform with four sloping sides—like a chopped-off pyramid. Ziggurats are made of mud-bricks—the building material of choice in the Near East, as stone is rare Ziggurats were not only a visual focal point of the city, they were a symbolic one, as well—they were at the heart of the theocratic political system (a theocracy is a type of government where a god is recognized as the ruler, and the state officials operate on the god’s behalf). So, seeing the ziggurat towering above the city, one made a visual connection to the god or goddess honored there, but also recognized that deity's political authority Excavators of the White Temple estimate that it would have taken 1500 laborers working on average ten hours per day for about five years to build the last major revetment (stone facing) of its massive underlying terrace (the open areas surrounding the White Temple at the top of the ziggurat) o Proabably some sort of forced labor involved The sides of the ziggurat were very broad and sloping but broken up by recessed stripes or bands from top to bottom (see digital reconstruction, above), which would have made a stunning pattern in morning or afternoon sunlight. -

Marten Stol WOMEN in the ANCIENT NEAR EAST

Marten Stol WOMEN IN THE ANCIENT NEAR EAST Marten Stol Women in the Ancient Near East Marten Stol Women in the Ancient Near East Translated by Helen and Mervyn Richardson ISBN 978-1-61451-323-0 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-1-61451-263-9 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-1-5015-0021-3 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivs 3.0 License. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by-nc-nd/3.0/ Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A CIP catalog record for this book has been applied for at the Library of Congress. Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. Original edition: Vrouwen van Babylon. Prinsessen, priesteressen, prostituees in de bakermat van de cultuur. Uitgeverij Kok, Utrecht (2012). Translated by Helen and Mervyn Richardson © 2016 Walter de Gruyter Inc., Boston/Berlin Cover Image: Marten Stol Typesetting: Dörlemann Satz GmbH & Co. KG, Lemförde Printing and binding: cpi books GmbH, Leck ♾ Printed on acid-free paper Printed in Germany www.degruyter.com Table of Contents Introduction 1 Map 5 1 Her outward appearance 7 1.1 Phases of life 7 1.2 The girl 10 1.3 The virgin 13 1.4 Women’s clothing 17 1.5 Cosmetics and beauty 47 1.6 The language of women 56 1.7 Women’s names 58 2 Marriage 60 2.1 Preparations 62 2.2 Age for marrying 66 2.3 Regulations 67 2.4 The betrothal 72 2.5 The wedding 93 2.6 -

Theologika 2019-2 Final.Indd

RESUMEN “Las cartas de Mari y el profetismo bíblico: Similitudes y diferencias – Parte II”— Este artículo es la segunda parte de un estudio de dos partes. En la primera parte, se desarrolló la descripción del profetismo bíblico, su naturaleza y características, con el fin de comprender los conceptos básicos de los fenómenos proféticos. Se describió la terminología utili- zada por las Escrituras para descubrir la naturaleza de los profetas bí- blicos. En este segundo artículo, se sigue el mismo procedimiento con las cartas de Mari y se ofrece una comparación entre estos dos registros para establecer su relación, similitudes y diferencias. Como resultado de esta evaluación, se establece que aunque existen algunas similitudes entre estos dos grupos, existen diferencias sustanciales. El profetismo bíblico se considera único y no encuentra su origen en ningún otro fenómeno antiguo sino en Dios mismo. Palabras clave: profetas, cartas de Mari, profetismo bíblico, Antiguo Cercano Oriente ABSTRACT “Mari Letters and Biblical Prophetism: Similarities and Differences— Part II”— This article is part two of a two-part paper. In the first part, the description of biblical prophetism, its nature, and features, were de- veloped in order to understand the basics of the prophetic phenomena. The terminology used by the Scriptures was described in order to find out the nature of the biblical prophets. In this second article, the same is done with Mari letters and a comparison is offered between these two records in order to establish their relationship, similarities, and differ- ences. As the result of this assessment, it is established that though there are some similarities between these two groups, there are substantial dif- ferences. -

National Museum of Aleppo As a Model)

Strategies for reconstructing and restructuring of museums in post-war places (National Museum of Aleppo as a Model) A dissertation submitted at the Faculty of Philosophy and History at the University of Bern for the doctoral degree by: Mohamad Fakhro (Idlib – Syria) 20/02/2020 Prof. Dr. Mirko Novák, Institut für Archäologische Wissenschaften der Universität Bern and Dr. Lutz Martin, Stellvertretender Direktor, Vorderasiatisches Museum, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin Fakhro. Mohamad Hutmatten Str.12 D-79639 Grenzach-Wyhlen Bern, 25.11.2019 Original document saved on the web server of the University Library of Bern This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial-No derivative works 2.5 Switzerland licence. To see the licence go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/2.5/ch/ or write to Creative Commons, 171 Second Street, Suite 300, San Francisco, California 94105, USA Copyright Notice This document is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial-No derivative works 2.5 Switzerland. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/2.5/ch/ You are free: to copy, distribute, display, and perform the work Under the following conditions: Attribution. You must give the original author credit. Non-Commercial. You may not use this work for commercial purposes. No derivative works. You may not alter, transform, or build upon this work.. For any reuse or distribution, you must take clear to others the license terms of this work. Any of these conditions can be waived if you get permission from the copyright holder. Nothing in this license impairs or restricts the author’s moral rights according to Swiss law. -

Two Weights from Temple N at Tell Mardikh-Ebla, Syria: a Link Between Metrology and Cultic Activities in the Second Millennium Bc?

TWO WEIGHTS FROM TEMPLE N AT TELL MARDIKH-EBLA, SYRIA: A LINK BETWEEN METROLOGY AND CULTIC ACTIVITIES IN THE SECOND MILLENNIUM BC? E. Ascalone and L. Peyronel Università di Roma“La Sapienza” The study of ancient Near Eastern metrology is part of the Lower Town (Matthiae 1985: pl. 54; a specific field of research that offers the possibil- 1989a: 150–52, fig. 31, pls. 105, 106), not far from ity to connect information from economic texts the slope of the Acropolis, to the east of the sacred with objects that were used in the pre-monetary area of Ishtar (Temple P2, Monument P3 and the system either for everyday exchange operations Cistern Square with the favissae).1 It was prob- or for “international” commercial transactions. ably built at the beginning of Middle Bronze I (ca. The importance of an approach that takes into 2000–1900 BC) and was destroyed at the end of consideration metrological standards with all the Middle Bronze II, around 1650–1600 BC. The technical matters concerned, as well as the archaeo- temple is formed by a single longitudinal cella logical context of weights and the relationships (L.2500) with a low, 4 m thick mudbrick bench between specimens and other broad functional along the rear wall (M.2501), while the north classes of materials (such as unfinished objects, (M.2393) and south (M.2502) walls are 3 m thick. unworked stones or lumps of metals, administra- The cella is 7.5 m wide and measures 12 m on the tive indicators, and precious items), has been noted preserved long side. -

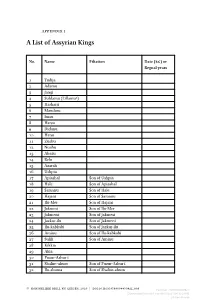

Downloaded from Brill.Com09/30/2021 04:32:21AM Via Free Access 198 Appendix I

Appendix I A List of Assyrian Kings No. Name Filiation Date (BC) or Regnal years 1 Tudija 2 Adamu 3 Jangi 4 Suhlamu (Lillamua) 5 Harharu 6 Mandaru 7 Imsu 8 Harsu 9 Didanu 10 Hanu 11 Zuabu 12 Nuabu 13 Abazu 14 Belu 15 Azarah 16 Ushpia 17 Apiashal Son of Ushpia 18 Hale Son of Apiashal 19 Samanu Son of Hale 20 Hajani Son of Samanu 21 Ilu-Mer Son of Hajani 22 Jakmesi Son of Ilu-Mer 23 Jakmeni Son of Jakmesi 24 Jazkur-ilu Son of Jakmeni 25 Ilu-kabkabi Son of Jazkur-ilu 26 Aminu Son of Ilu-kabkabi 27 Sulili Son of Aminu 28 Kikkia 29 Akia 30 Puzur-Ashur I 31 Shalim-ahum Son of Puzur-Ashur I 32 Ilu-shuma Son of Shalim-ahum © Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, 2020 | doi:10.1163/9789004430921_008 Fei Chen - 9789004430921 Downloaded from Brill.com09/30/2021 04:32:21AM via free access 198 Appendix I No. Name Filiation Date (BC) or Regnal years 33 Erishum I Son of Ilu-shuma 1974–1935 34 Ikunum Son of Erishum I 1934–1921 35 Sargon I Son of Ikunum 1920–1881 36 Puzur-Ashur II Son of Sargon I 1880–1873 37 Naram-Sin Son of Puzur-Ashur II 1872–1829/19 38 Erishum II Son of Naram-Sin 1828/18–1809b 39 Shamshi-Adad I Son of Ilu-kabkabic 1808–1776 40 Ishme-Dagan I Son of Shamshi-Adad I 40 yearsd 41 Ashur-dugul Son of Nobody 6 years 42 Ashur-apla-idi Son of Nobody 43 Nasir-Sin Son of Nobody No more than 44 Sin-namir Son of Nobody 1 year?e 45 Ibqi-Ishtar Son of Nobody 46 Adad-salulu Son of Nobody 47 Adasi Son of Nobody 48 Bel-bani Son of Adasi 10 years 49 Libaja Son of Bel-bani 17 years 50 Sharma-Adad I Son of Libaja 12 years 51 Iptar-Sin Son of Sharma-Adad I 12 years