Optimism and Rage

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oral History Interview with Ann Wilson, 2009 April 19-2010 July 12

Oral history interview with Ann Wilson, 2009 April 19-2010 July 12 Funding for this interview was provided by the Terra Foundation for American Art. Funding for the digital preservation of this interview was provided by a grant from the Save America's Treasures Program of the National Park Service. Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Preface The following oral history transcript is the result of a recorded interview with Ann Wilson on 2009 April 19-2010 July 12. The interview took place at Wilson's home in Valatie, New York, and was conducted by Jonathan Katz for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. This transcript has been lightly edited for readability by the Archives of American Art. The reader should bear in mind that they are reading a transcript of spoken, rather than written, prose. Interview ANN WILSON: [In progress] "—happened as if it didn't come out of himself and his fixation but merged. It came to itself and is for this moment without him or her, not brought about by him or her but is itself and in this sudden seeing of itself, we make the final choice. What if it has come to be without external to us and what we read it to be then and heighten it toward that reading? If we were to leave it alone at this point of itself, our eyes aging would no longer be able to see it. External and forget the internal ordering that brought it about and without the final decision of what that ordering was about and our emphasis of it, other eyes would miss the chosen point and feel the lack of emphasis. -

2017 Abstracts

Abstracts for the Annual SECAC Meeting in Columbus, Ohio October 25th-28th, 2017 Conference Chair, Aaron Petten, Columbus College of Art & Design Emma Abercrombie, SCAD Savannah The Millennial and the Millennial Female: Amalia Ulman and ORLAN This paper focuses on Amalia Ulman’s digital performance Excellences and Perfections and places it within the theoretical framework of ORLAN’s surgical performance series The Reincarnation of Saint Orlan. Ulman’s performance occurred over a twenty-one week period on the artist’s Instagram page. She posted a total of 184 photographs over twenty-one weeks. When viewed in their entirety and in relation to one another, the photographs reveal a narrative that can be separated into three distinct episodes in which Ulman performs three different female Instagram archetypes through the use of selfies and common Instagram image tropes. This paper pushes beyond the casual connection that has been suggested, but not explored, by art historians between the two artists and takes the comparison to task. Issues of postmodern identity are explored as they relate to the Internet culture of the 1990s when ORLAN began her surgery series and within the digital landscape of the Web 2.0 age that Ulman works in, where Instagram is the site of her performance and the selfie is a medium of choice. Abercrombie situates Ulman’s “image-body” performance within the critical framework of feminist performance practice, using the postmodern performance of ORLAN as a point of departure. J. Bradley Adams, Berry College Controlled Nature Focused on gardens, Adams’s work takes a range of forms and operates on different scales. -

Surface Work

Surface Work Private View 6 – 8pm, Wednesday 11 April 2018 11 April – 19 May 2018 Victoria Miro, Wharf Road, London N1 7RW 11 April – 16 June 2018 Victoria Miro Mayfair, 14 St George Street, London W1S 1FE Image: Adriana Varejão, Azulejão (Moon), 2018 Oil and plaster on canvas, 180 x 180cm. Photograph: Jaime Acioli © the artist, courtesy Victoria Miro, London / Venice Taking place across Victoria Miro’s London galleries, this international, cross-generational exhibition is a celebration of women artists who have shaped and transformed, and continue to influence and expand, the language and definition of abstract painting. More than 50 artists from North and South America, Europe, the Middle East and Asia are represented. The earliest work, an ink on paper work by the Russian Constructivist Liubov Popova, was completed in 1918. The most recent, by contemporary artists including Adriana Varejão, Svenja Deininger and Elizabeth Neel, have been made especially for the exhibition. A number of the artists in the exhibition were born in the final decades of the nineteenth century, while the youngest, Beirut-based Dala Nasser, was born in 1990. Work from every decade between 1918 and 2018 is featured. Surface Work takes its title from a quote by the Abstract Expressionist painter Joan Mitchell, who said: ‘Abstract is not a style. I simply want to make a surface work.’ The exhibition reflects the ways in which women have been at the heart of abstract art’s development over the past century, from those who propelled the language of abstraction forward, often with little recognition, to those who have built upon the legacy of earlier generations, using abstraction to open new paths to optical, emotional, cultural, and even political expression. -

The Literacy Practices of Feminist Consciousness- Raising: an Argument for Remembering and Recitation

LEUSCHEN, KATHLEEN T., Ph.D. The Literacy Practices of Feminist Consciousness- Raising: An Argument for Remembering and Recitation. (2016) Directed by Dr. Nancy Myers. 169 pp. Protesting the 1968 Miss America Pageant in Atlantic City, NJ, second-wave feminists targeted racism, militarism, excessive consumerism, and sexism. Yet nearly fifty years after this protest, popular memory recalls these activists as bra-burners— employing a widespread, derogatory image of feminist activists as trivial and laughably misguided. Contemporary academics, too, have critiqued second-wave feminism as a largely white, middle-class, and essentialist movement, dismissing second-wave practices in favor of more recent, more “progressive” waves of feminism. Following recent rhetorical scholarly investigations into public acts of remembering and forgetting, my dissertation project contests the derogatory characterizations of second-wave feminist activism. I use archival research on consciousness-raising groups to challenge the pejorative representations of these activists within academic and popular memory, and ultimately, to critique telic narratives of feminist progress. In my dissertation, I analyze a rich collection of archival documents— promotional materials, consciousness-raising guidelines, photographs, newsletters, and reflective essays—to demonstrate that consciousness-raising groups were collectives of women engaging in literacy practices—reading, writing, speaking, and listening—to make personal and political material and discursive change, between and across differences among women. As I demonstrate, consciousness-raising, the central practice of second-wave feminism across the 1960s and 1970s, developed out of a collective rhetorical theory that not only linked personal identity to political discourses, but also 1 linked the emotional to the rational in the production of knowledge. -

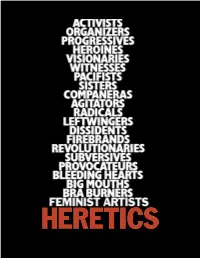

Heretics Proposal.Pdf

A New Feature Film Directed by Joan Braderman Produced by Crescent Diamond OVERVIEW ry in the first person because, in 1975, when we started meeting, I was one of 21 women who THE HERETICS is a feature-length experimental founded it. We did worldwide outreach through documentary film about the Women’s Art Move- the developing channels of the Women’s Move- ment of the 70’s in the USA, specifically, at the ment, commissioning new art and writing by center of the art world at that time, New York women from Chile to Australia. City. We began production in August of 2006 and expect to finish shooting by the end of June One of the three youngest women in the earliest 2007. The finish date is projected for June incarnation of the HERESIES collective, I remem- 2008. ber the tremendous admiration I had for these accomplished women who gathered every week The Women’s Movement is one of the largest in each others’ lofts and apartments. While the political movement in US history. Why then, founding collective oversaw the journal’s mis- are there still so few strong independent films sion and sustained it financially, a series of rela- about the many specific ways it worked? Why tively autonomous collectives of women created are there so few movies of what the world felt every aspect of each individual themed issue. As like to feminists when the Movement was going a result, hundreds of women were part of the strong? In order to represent both that history HERESIES project. We all learned how to do lay- and that charged emotional experience, we out, paste-ups and mechanicals, assembling the are making a film that will focus on one group magazines on the floors and walls of members’ in one segment of the larger living spaces. -

Faith Ringgold Interviewed by Dena Muller Date: Sunday, Nov

NYFAI Interview: Faith Ringgold interviewed by Dena Muller Date: Sunday, Nov. 25th, 2007 D.M. O.k. it’s November 25th of 2007, we’re at Faith Ringgold’s studio in New Jersey, and conducting the oral history interview for the New York Feminist Art Institute. My name is Dena Muller interviewing Faith Ringgold. So, we’re going to start just talking about the earliest history of the New York Feminist Art Institute. The gala to raise money to open the New York Feminist Art Institute was in March of 1979 and it was at the World Trade Center and the piece there by Louise Nevelson was being featured as part of the gala celebration and Louise was there. F.R. An outdoor piece. D.M. No, the indoor piece that was there (in lobby). F.R. The indoor piece. Now I’m completely foggy on that one. D.M. I raised it just to say do you remember the gala at all? You were involved in the New York Feminist Art Institute later, but do you remember the gala happening or do you remember hearing anything about it. F.R. Well, I’ll tell you, I’ve been in so many galas (laughter). D.M. We just want to . F.R. I remember there were lots of exciting things that happened. Most every week there was something, something to remember, something really historically moving that had to do with the feminist movement. And I know now that there is nothing. There is nothing. D.M. (hesitate) Right. F.R. -

A Finding Aid to the Lucy R. Lippard Papers, 1930S-2007, Bulk 1960-1990

A Finding Aid to the Lucy R. Lippard Papers, 1930s-2007, bulk 1960s-1990, in the Archives of American Art Stephanie L. Ashley and Catherine S. Gaines Funding for the processing of this collection was provided by the Terra Foundation for American Art 2014 May Archives of American Art 750 9th Street, NW Victor Building, Suite 2200 Washington, D.C. 20001 https://www.aaa.si.edu/services/questions https://www.aaa.si.edu/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 2 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 3 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 4 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 4 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 6 Series 1: Biographical Material, circa 1960s-circa 1980s........................................ 6 Series 2: Correspondence, 1950s-2006.................................................................. 7 Series 3: Writings, 1930s-1990s........................................................................... -

Shulamith Firestone 1945–2012 2

Shulamith Firestone 1945–2012 2 Photograph courtesy of Lori Hiris. New York, 1997. Memorial for Shulamith Firestone St. Mark’s Church in the Bowery, Parish Hall September 23, 2012 Program 4:00–6:00 pm Laya Firestone Seghi Eileen Myles Kathie Sarachild Jo Freeman Ti-Grace Atkinson Marisa Figueiredo Tributes from: Anne Koedt Peggy Dobbins Bev Grant singing May the Work That I Have Done Speak For Me Kate Millett Linda Klein Roxanne Dunbar Robert Roth 3 Open floor for remembrances Lori Hiris singing Hallelujah Photograph courtesy of Lori Hiris. New York, 1997. Reception 6:00–6:30 4 Shulamith Firestone Achievements & Education Writer: 1997 Published Airless Spaces. Semiotexte Press 1997. 1970–1993 Published The Dialectic of Sex, Wm. Morrow, 1970, Bantam paperback, 1971. – Translated into over a dozen languages, including Japanese. – Reprinted over a dozen times up through Quill trade edition, 1993. – Contributed to numerous anthologies here and abroad. Editor: Edited the first feminist magazine in the U.S.: 1968 Notes from the First Year: Women’s Liberation 1969 Notes from the Second Year: Women’s Liberation 1970 Consulting Editor: Notes from the Third Year: WL Organizer: 1961–3 Activist in early Civil Rights Movement, notably St. Louis c.o.r.e. (Congress on Racial Equality) 1967–70 Founder-member of Women’s Liberation Movement, notably New York Radical Women, Redstockings, and New York Radical Feminists. Visual Artist: 1978–80 As an artist for the Cultural Council Foundation’s c.e.t.a. Artists’ Project (the first government funded arts project since w.p.a.): – Taught art workshops at Arthur Kill State Prison For Men – Designed and executed solo-outdoor mural on the Lower East Side for City Arts Workshop – As artist-in-residence at Tompkins Square branch of the New York Public Library, developed visual history of the East Village in a historical mural project. -

Double Vision: Woman As Image and Imagemaker

double vision WOMAN AS IMAGE AND IMAGEMAKER Everywhere in the modern world there is neglect, the need to be recognized, which is not satisfied. Art is a way of recognizing oneself, which is why it will always be modern. -------------- Louise Bourgeois HOBART AND WILLIAM SMITH COLLEGES The Davis Gallery at Houghton House Sarai Sherman (American, 1922-) Pas de Deux Electrique, 1950-55 Oil on canvas Double Vision: Women’s Studies directly through the classes of its Woman as Image and Imagemaker art history faculty members. In honor of the fortieth anniversary of Women’s The Collection of Hobart and William Smith Colleges Studies at Hobart and William Smith Colleges, contains many works by women artists, only a few this exhibition shows a selection of artworks by of which are included in this exhibition. The earliest women depicting women from The Collections of the work in our collection by a woman is an 1896 Colleges. The selection of works played off the title etching, You Bleed from Many Wounds, O People, Double Vision: the vision of the women artists and the by Käthe Kollwitz (a gift of Elena Ciletti, Professor of vision of the women they depicted. This conjunction Art History). The latest work in the collection as of this of women artists and depicted women continues date is a 2012 woodcut, Glacial Moment, by Karen through the subtitle: woman as image (woman Kunc (a presentation of the Rochester Print Club). depicted as subject) and woman as imagemaker And we must also remember that often “anonymous (woman as artist). Ranging from a work by Mary was a woman.” Cassatt from the early twentieth century to one by Kara Walker from the early twenty-first century, we I want to take this opportunity to dedicate this see depictions of mothers and children, mythological exhibition and its catalog to the many women and figures, political criticism, abstract figures, and men who have fostered art and feminism for over portraits, ranging in styles from Impressionism to forty years at Hobart and William Smith Colleges New Realism and beyond. -

WOMAN's. ART JOURNAL

WOMAN's. ART JOURNAL (on the cover): Alice Nee I, Mary D. Garrard (1977), FALL I WINTER 2006 VOLUME 27, NUMBER 2 oil on canvas, 331/4" x 291/4". Private collection. 2 PARALLEL PERSPECTIVES By Joan Marter and Margaret Barlow PORTRAITS, ISSUES AND INSIGHTS 3 ALICE EEL A D M E By Mary D. Garrard EDITORS JOAN MARTER AND MARGARET B ARLOW 8 ALI CE N EEL'S WOMEN FROM THE 1970s: BACKLASH TO FAST FORWA RD By Pamela AHara BOOK EDITOR : UTE TELLINT 12 ALI CE N EE L AS AN ABSTRACT PAINTER FOUNDING EDITOR: ELSA HONIG FINE By Mira Schor EDITORIAL BOARD 17 REVISITING WOMANHOUSE: WELCOME TO THE (DECO STRUCTED) 0 0LLHOUSE NORMA BROUDE NANCY MOWLL MATHEWS By Temma Balducci THERESE DoLAN MARTIN ROSENBERG 24 NA CY SPERO'S M USEUM I CURSIO S: !SIS 0 THE THR ES HOLD MARY D. GARRARD PAMELA H. SIMPSON By Deborah Frizzell SALOMON GRIMBERG ROBERTA TARBELL REVIEWS ANN SUTHERLAND HARRis JUDITH ZILCZER 33 Reclaiming Female Agency: Feminist Art History after Postmodernism ELLEN G. LANDAU EDITED BY N ORMA BROUDE AND MARY D. GARRARD Reviewed by Ute L. Tellini PRODUCTION, AND DESIGN SERVICES 37 The Lost Tapestries of the City of Ladies: Christine De Pizan's O LD CITY P UBLISHING, INC. Renaissance Legacy BYS uSAN GROAG BELL Reviewed by Laura Rinaldi Dufresne Editorial Offices: Advertising and Subscriptions: Woman's Art journal Ian MeUanby 40 Intrepid Women: Victorian Artists Travel Rutgers University Old City Publishing, Inc. EDITED BY JORDANA POMEROY Reviewed by Alicia Craig Faxon Dept. of Art History, Voorhees Hall 628 North Second St. -

Une Bibliographie Commentée En Temps Réel : L'art De La Performance

Une bibliographie commentée en temps réel : l’art de la performance au Québec et au Canada An Annotated Bibliography in Real Time : Performance Art in Quebec and Canada 2019 3e édition | 3rd Edition Barbara Clausen, Jade Boivin, Emmanuelle Choquette Éditions Artexte Dépôt légal, novembre 2019 Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec Bibliothèque et Archives du Canada. ISBN : 978-2-923045-36-8 i Résumé | Abstract 2017 I. UNE BIBLIOGraPHIE COMMENTÉE 351 Volet III 1.11– 15.12. 2017 I. AN ANNOTATED BIBLIOGraPHY Lire la performance. Une exposition (1914-2019) de recherche et une série de discussions et de projections A B C D E F G H I Part III 1.11– 15.12. 2017 Reading Performance. A Research J K L M N O P Q R Exhibition and a Series of Discussions and Screenings S T U V W X Y Z Artexte, Montréal 321 Sites Web | Websites Geneviève Marcil 368 Des écrits sur la performance à la II. DOCUMENTATION 2015 | 2017 | 2019 performativité de l’écrit 369 From Writings on Performance to 2015 Writing as Performance Barbara Clausen. Emmanuelle Choquette 325 Discours en mouvement 370 Lieux et espaces de la recherche 328 Discourse in Motion 371 Research: Sites and Spaces 331 Volet I 30.4. – 20.6.2015 | Volet II 3.9 – Jade Boivin 24.10.201 372 La vidéo comme lieu Une bibliographie commentée en d’une mise en récit de soi temps réel : l’art de la performance au 374 Narrative of the Self in Video Art Québec et au Canada. Une exposition et une série de 2019 conférences Part I 30.4. -

The Evolution of Craft in Contemporary Feminist Art

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont Scripps Senior Theses Scripps Student Scholarship 2010 The volutE ion of Craft in onC temporary Feminist Art Carolyn E. Packer Scripps College Recommended Citation Packer, Carolyn E., "The vE olution of Craft in onC temporary Feminist Art" (2010). Scripps Senior Theses. Paper 23. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/scripps_theses/23 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Scripps Student Scholarship at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Scripps Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Evolution of Craft in Contemporary Feminist Art By: Carolyn Elizabeth Packer SUBMITTED TO SCRIPPS COLLEGE IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF ARTS Professor Susan Rankaitis Professor Nancy Macko May 3, 2010 This Senior Project is dedicated to my Grandmother, Gloria Carolyn Reich. Thank you for giving me the invaluable skills that have inspired my art and being the model for woman I strive to become. Thank you also to Professor Susan Rankaitis for inspiring my dedication to this project, and to Professor Nancy Macko for being such a supportive and encouraging advisor, thesis reader, and role model. 2 Women’s art is rooted in a long history of traditional craft practices. It is said that during the times of male-dominated society, if a woman had any brains she would explore her creativity through quilting, clothing design and needlework; creating utilitarian objects for the household to serve her husband and family. Being a part of an extended family lineage of talented and inspired craftswomen has provoked me to analyze the evolution of craft from a domestic practice into a higher form of feminist art.