Athens 1890-1940.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

11. Heine and Shakespeare

https://www.openbookpublishers.com © 2021 Roger Paulin This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the text; to adapt the text and to make commercial use of the text providing attribution is made to the authors (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Attribution should include the following information: Roger Paulin, From Goethe to Gundolf: Essays on German Literature and Culture. Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2021, https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0258 Copyright and permissions for the reuse of many of the images included in this publication differ from the above. Copyright and permissions information for images is provided separately in the List of Illustrations. In order to access detailed and updated information on the license, please visit, https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0258#copyright Further details about CC-BY licenses are available at, https://creativecommons.org/ licenses/by/4.0/ All external links were active at the time of publication unless otherwise stated and have been archived via the Internet Archive Wayback Machine at https://archive.org/web Updated digital material and resources associated with this volume are available at https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0258#resources Every effort has been made to identify and contact copyright holders and any omission or error will be corrected if notification is made to the publisher. ISBN Paperback: 9781800642126 ISBN Hardback: 9781800642133 ISBN Digital (PDF): 9781800642140 ISBN Digital ebook (epub): 9781800642157 ISBN Digital ebook (mobi): 9781800642164 ISBN Digital (XML): 9781800642171 DOI: 10.11647/OBP.0258 Cover photo and design by Andrew Corbett, CC-BY 4.0. -

PDF EN Für Web Ganz

MUNICH MOZART´S STAY The life and work of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart is closely connected to Munich, a centre of the German music patronage. Two of his most famous works Mozart composed in the residence city of Munich: On the 13th January, 1775 the premiere from „La finta giardinera “took place, on the 29th January, 1781 the opera "Idomeneo" was launched at Cuvilliés Theater. Already during his first trip at the age of six years Wolfgang played together with his sister Nannerl for Elector Maximilian Joseph III. The second visit followed a year later, in June, 1763. From Munich the Mozart family started to their three year European journey to Paris and London. On the way back from this triumphal journey they stopped in Munich again and Mozart gave concerts at the Emperors court. Main focus of the next trip to Munich (1774 – in 1775) was the premiere of the opera "La finta giardiniera" at the Salvatortheater. In 1777 when Wolfgang and his mother were on the way to Paris Munich was destination again and they stayed 14 days in the Isar city. Unfortunately, at that time Wolfgang aspired in vain to and permanent employment. Idomeneo, an opera which Mozart had composed by order of Elector Karl Theodor, was performed in Munich for the first time at the glamorous rococo theatre in the Munich palace, the Cuvilliés Theater. With pleasure he would have remained in Munich, however, there was, unfortunately, none „vacatur “for him again. In 1790 Mozart came for the last time to Munich on his trip to the coronation of Leopold II in Frankfurt. -

“The Semiotics of the Imagery of the Greek War of Independence. from Delacroix to the Frieze in Otto’S Palace, the Current Hellenic Parliament”

American Research Journal of Humanities & Social Science (ARJHSS)R) 2020 American Research Journal of Humanities & Social Science (ARJHSS) E-ISSN: 2378-702X Volume-03, Issue-01, pp 36-41 January-2020 www.arjhss.com Research Paper Open Access “The Semiotics of the Imagery of the Greek War of Independence. From Delacroix to the Frieze in Otto’s Palace, The Current Hellenic Parliament”. Markella-Elpida Tsichla University of Patras *Corresponding Author: Markella-Elpida Tsichla ABSTRACT:- The iconography of the Greek War of Independence is quite broad and it includes both real and imaginary themes. Artists who were inspired by this particular and extremely important historical event originated from a variety of countries, some were already well-known, such as Eugène Delacroix, others were executing official commissions from kings of Western countries, and most of them were driven by the spirit of romanticism. This paper shall not so much focus on matters of art criticism, but rather explore the manner in which facts have been represented in specific works of art, referring to political, religious and cultural issues, which are still relevant to this day. In particular, I shall comment on The Massacre at Chios by Eugène Delacroix, painted in 1824, the 39 Scenes from the Greek War of Independence by Peter von Hess, painted in 1835 and commissioned by King Ludwig I of Bavaria, and the frieze in the Trophy Room (currently Eleftherios Venizelos Hall) in Otto’s palace in Athens, currently housing the Hellenic Parliament, themed around the Greek War of Independence and the subsequent events. This great work was designed by German sculptor Ludwig Michael Schantahaler in 1840 and “transferred” to the walls of the hall by a group of Greek and German artists. -

The Artistic Patronage of Albrecht V and the Creation of Catholic Identity in Sixteenth

The Artistic Patronage of Albrecht V and the Creation of Catholic Identity in Sixteenth- Century Bavaria A dissertation presented to the faculty of the College of Fine Arts of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Adam R. Gustafson June 2011 © 2011 Adam R. Gustafson All Rights Reserved 2 This dissertation titled The Artistic Patronage of Albrecht V and the Creation of Catholic Identity in Sixteenth- Century Bavaria by ADAM R. GUSTAFSON has been approved for the School of Interdisciplinary Arts and the College of Fine Arts _______________________________________________ Dora Wilson Professor of Music _______________________________________________ Charles A. McWeeny Dean, College of Fine Arts 3 ABSTRACT GUSTAFSON, ADAM R., Ph.D., June 2011, Interdisciplinary Arts The Artistic Patronage of Albrecht V and the Creation of Catholic Identity in Sixteenth- Century Bavaria Director of Dissertation: Dora Wilson Drawing from a number of artistic media, this dissertation is an interdisciplinary approach for understanding how artworks created under the patronage of Albrecht V were used to shape Catholic identity in Bavaria during the establishment of confessional boundaries in late sixteenth-century Europe. This study presents a methodological framework for understanding early modern patronage in which the arts are necessarily viewed as interconnected, and patronage is understood as a complex and often contradictory process that involved all elements of society. First, this study examines the legacy of arts patronage that Albrecht V inherited from his Wittelsbach predecessors and developed during his reign, from 1550-1579. Albrecht V‟s patronage is then divided into three areas: northern princely humanism, traditional religion and sociological propaganda. -

NEW EOT-English:Layout 1

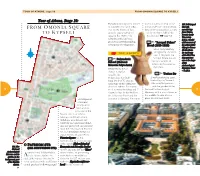

TOUR OF ATHENS, stage 10 FROM OMONIA SQUARE TO KYPSELI Tour of Athens, Stage 10: Papadiamantis Square), former- umental staircases lead to the 107. Bell-shaped FROM MONIA QUARE ly a garden city (with villas, Ionian style four-column propy- idol with O S two-storey blocks of flats, laea of the ground floor, a copy movable legs TO K YPSELI densely vegetated) devel- of the northern hall of the from Thebes, oped in the 1920’s - the Erechteion ( page 13). Boeotia (early 7th century suburban style has been B.C.), a model preserved notwithstanding 1.2 ¢ “Acropol Palace” of the mascot of subsequent development. Hotel (1925-1926) the Athens 2004 Olympic Games A five-story building (In the photo designed by the archi- THE SIGHTS: an exact copy tect I. Mayiasis, the of the idol. You may purchase 1.1 ¢Polytechnic Acropol Palace is a dis- tinctive example of one at the shops School (National Athens Art Nouveau ar- of the Metsovio Polytechnic) Archaeological chitecture. Designed by the ar- Resources Fund – T.A.P.). chitect L. Kaftan - 1.3 tzoglou, the ¢Tositsa Str Polytechnic was built A wide pedestrian zone, from 1861-1876. It is an flanked by the National archetype of the urban tra- Metsovio Polytechnic dition of Athens. It compris- and the garden of the 72 es of a central building and T- National Archaeological 73 shaped wings facing Patision Museum, with a row of trees in Str. It has two floors and the the middle, Tositsa Str is a development, entrance is elevated. Two mon- place to relax and stroll. -

Study Tour to Greece~

Tour is open to: • All students • Alumnae Trip Highlights~ Enhance your studies at some of the greatest ancient sites in the Study Tour to world. We owe our western view of the world to the modern- thinking Greeks. Theatre and psychology come together in this 10- Greece~ day trip to Athens and Santorini. Daily excursions take us to Delphi, the ancient center of the Earth the Naval Stone, the Parthenon, the With Professor Roxanne Amico and Acropolis, the Agora, Mycene and Epidaurus, Theatre of Dionysus, Lycabettus Hill and wonderful museums. You will enjoy great food Dr. Sharon Himmanen and nightlife in historic Plaka, the location of our hotel at the foot of May 14--May 25, 2017 the Acropolis and some free time in Syntagma Square in Athens, the seaport of Piraeus and the old flea market and shopping area of Course: THS / PSY 260- (1 credit) Monastiraki. Reading lists will be available for all travelers. In the Footsteps of the Ancient Greeks Students seeking course credit will have play readings and writing assignments focused on the relationship between ancient psychology Students are encouraged to take class if and philosophy and Greek drama. participating in travel component. THS / PSY 260 are not “free—standing” Included in Program Fee: classes. o Round Trip shuttle between campus and the airport o International flights to/from Athens Contact: Mary Anne Kucserik o Airport transfers in Athens Director of Global Initiatives & o 8 overnights in twin-shared accommodations in Athens International Programs & 2 overnights in Santorini, with daily breakfast included Curtis 201 o One welcome and one farewell dinner included o Round trip transfer to Santorini to include guided [email protected] cultural visits and entries 610-606-4666, ext. -

Title: “The Agrarian Question: the Agrarian Movement and Issues of Land Ownership in Greece, 1821-1923” Author: Kaiti Aroni

Title: “The agrarian question: the agrarian movement and issues of land ownership in Greece, 1821‐1923” Author: Kaiti Aroni‐Tsichli How to cite this article: Aroni‐Tsichli, Kaiti. 2014. “The agrarian question: the agrarian movement and issues of land ownership in Greece, 1821‐1923”. Martor 19: 43‐62. Published by: Editura MARTOR (MARTOR Publishing House), Muzeul Țăranului Român (The Museum of the Romanian Peasant) URL: http://martor.muzeultaranuluiroman.ro/archive/martor‐19‐2014/ Martor (The Museum of the Romanian Peasant Anthropology Review) is a peer‐reviewed academic journal established in 1996, with a focus on cultural and visual anthropology, ethnology, museum studies and the dialogue among these disciplines. Martor review is published by the Museum of the Romanian Peasant. Its aim is to provide, as widely as possible, a rich content at the highest academic and editorial standards for scientific, educational and (in)formational goals. Any use aside from these purposes and without mentioning the source of the article(s) is prohibited and will be considered an infringement of copyright. Martor (Revue d’Anthropologie du Musée du Paysan Roumain) est un journal académique en système peer‐review fondé en 1996, qui se concentre sur l’anthropologie visuelle et culturelle, l’ethnologie, la muséologie et sur le dialogue entre ces disciplines. La revue Martor est publiée par le Musée du Paysan Roumain. Son aspiration est de généraliser l’accès vers un riche contenu au plus haut niveau du point de vue académique et éditorial pour des objectifs scientifiques, éducatifs et informationnels. Toute utilisation au‐delà de ces buts et sans mentionner la source des articles est interdite et sera considérée une violation des droits de l’auteur. -

Destination Factsheets 2021

HEART OF Altötting BAVARIA TOP SIGHTSEEING SEASONAL HIGHLIGHTS TOP DAY HIGHLIGHTS 2021–22 EXCURSIONS 01 Chapel of Grace – with the “Black May: Pentecost weekend sees the 01 Burghausen – with the world’s Madonna” on the Baroque Chapel arrival of thousands of pilgrims on longest medieval castle (1.051 m) Square (Kapellplatz) foot May/June: Traditional beer-festi- 02 Munich – capital of Bavaria with Neobaroque papal Basilica val “Hofdult” with 2 local brewer- the Oktoberfest, museums … 02 St. Anna – Altötting’s largest ies, traditional Bavarian music and church and built due to the increase costumes (beginning 1 week after 03 Lake Chiemsee – with the fairytale of pilgrims pentecost) castle “Herrenchiemsee”, commis- July: Altötting Monastery Market sioned by Ludwig II 03 Museum: Jerusalem Panorama at the Chapel Square –one of three crucifixion panorama Nov./Dec.: Altötting Christmas paintings world-wide and protected Market (on weekends) with DID YOU by UNESCO numerous Christmas concerts in KNOW THAT … traditional style of the alps 04 Treasury & Pilgrimage Museum the bridal wreath of the world-fa- – wealth of artistic votive offerings mous Austrian Empress “Sissi” is to Altötting, the Place of Mercy, CITY’S on display in the Altötting-Trea- including famous “Golden Horse” HISTORY sury? Altötting and Oberammergau can 05 Incense Museum – reveals the 1489 marks the beginning of the be combined in a religious round myth and the 3,000 year history of pilgrimage to Altötting in venera- trip through Bavaria? incense tion of the Virgin Mary. Two healing © Heiner Heine (2) © miracles are reported from that year with the first one being described as follows: A young boy fell into a nearby river. -

New Evidence on the Origin of the Influence of Nietzsche and of the Idea of Immanent

fig. 1 G. de Chirico, Scatola di cerini e sigarette, ca 1904-1906 13 New Evidence on the Origin of the Influence of Nietzsche and of the Idea of Immanent Myth in Giorgio de Chirico: Mavìlis, Palamàs and the Early XX Century Athens Literary Scene Fabio Benzi There have been many attempts at identifying an influence of the Greek milieu on the young Gior- gio de Chirico. From his birth (1888) to his late adolescence, the artist lived in Greece, in Volos and especially Athens, until he moved to Munich in October 1906. So, he spent the first eighteen years of life – undoubtedly a formative moment for any young intellectual – mostly in Athens, where he also completed his first artistic studies in the Academy of Fine Arts of the Polytechnic School. As might be expected, research aimed at contextualizing and furthering the knowledge of pos- sible Hellenic influences on de Chirico’s artistic activity has focused so far on the specific analysis of the local painting scene, although with little or less than significant results. To be sure, we are not aware of any extant early painting from his Greek period, except for a negligible, small still life painted on cardboard, depicting a box of matches with a lit cigarette leaning against it (fig. 1); the verso shows an earlier copy of a detail of a chromolithography by Bel- gian painter Jan van Beers (Lier, 27 March 1852-Fay- aux-Loges, 17 November 1927), which we have iden- tified here (figs. 2, 3).1 If this copy is an example of the nearly photographic unyielding adherence by a young artist who might have not yet attended the academy, the small oil is actually a genre exercise, probably painted while de Chirico was still a student. -

When Crisis Becomes Form: Athens As a Paradigm Theophilos Tramboulis and Yorgos Tzirtzilakis

When Crisis Becomes Form: Athens as a Paradigm Theophilos Tramboulis and Yorgos Tzirtzilakis Documenta 14 in Athens: a glossary Documenta 14 (d14) was an undoubtedly important exhibition which triggered endless debate and controversy that continues today.1 The choice of Athens as a topological paradigm by Adam Szymczyk, an ingenious curator with expected and unexpected virtues, initially fired people’s appetite and enthusiasm. Yet what it ultimately managed to do was demythicize the event itself in a way, as well as demonstrate a series of dangers in the operation of the institution. At the same time it brought to light a series of innate ailments and fantasies of contemporary culture in Greece, which manifested themselves in a distorted and sometimes aggressive fashion. This is not without significance, since it functioned complementarily to—rather than independently of—the exhibition. In short, d14 served as a kind of double mirror with which we could see the cultural relation of Greece with Europe and the world, but also the reverse: that of Europe with Greece. So what was d14 in Athens? For now we must necessarily sidestep its contribution to making Athens and Greek culture a temporary center of international attention in order to focus on what must not be overlooked. The series of arguments below can be read individually or successively as a network of alternating commentary, but also through their diagonal intersections, ruptures, disagreements, and connections, where meaning is produced in a syncretic or dialectical way. D14 is the symptom from which all discourse around it begins. 1/11 A political metonymy The critical reception of d14 in Greece focused mainly on the institution and its operation; on its discursive and political context rather than the works, concerts, or lectures— generally speaking, the actual art and discourse presented by the exhibition. -

2020 Adoptions

Dimitris Arvanitakis: Head of the Publications Department Born in Zakynthos, Dimitris Arvanitakis is a graduate of the Department of Byzantine and Modern Greek Studies of the University of Athens. As a fellow of the Academy of Athens from 1995 to 1999, he conducted research for his doctoral dissertation at Istituto di Studi Bizantini e Postbizantini of Venice, which was successfully defended at the Ionian University in Corfu (1999). His scientific interests span a wide range of topics: social history, history of ideas and intellectual history, history of literature and historiography, Modern Greek and Italian history, and the formation of national states. Since 2000, he has been working at the Benaki Museum and since 2006 he has been in charge of the Publications Department. In his capacity as Head of Publications, he has overseen and coordinated the publication of a great number of the Museum’s exhibition and collections catalogues and has been scientific editor of many books, including the series Benaki Museum Library. Dimitris Arvanitakis has taught in postgraduate seminars in Greece and Italy, has organized scientific conferences and has edited a number of scientific volumes. Moreover, he has published many articles in scientific volumes, journals and conference proceedings. He is a member of the Editorial Secretariat of the Greek journal Ta Istorika and the Italian journal Periptero, member of the Review Team of the journal Giornale Storico della Letteratura Italiana, Scientific Director of the Casa di Ugo Foscolo / Hugo Foscolo’s House (Zakynthos), and since 2009 he has been a Member and Coordinator of the Scientific Committee which oversees the publication of Andreas Kalvos’ Works by the Benaki Museum. -

Planning Development of Kerameikos up to 35 International Competition 1 Historical and Urban Planning Development of Kerameikos

INTERNATIONAL COMPETITION FOR ARCHITECTS UP TO STUDENT HOUSING 35 HISTORICAL AND URBAN PLANNING DEVELOPMENT OF KERAMEIKOS UP TO 35 INTERNATIONAL COMPETITION 1 HISTORICAL AND URBAN PLANNING DEVELOPMENT OF KERAMEIKOS CONTENTS EARLY ANTIQUITY ......................................................................................................................... p.2-3 CLASSICAL ERA (478-338 BC) .................................................................................................. p.4-5 The municipality of Kerameis POST ANTIQUITY ........................................................................................................................... p.6-7 MIDDLE AGES ................................................................................................................................ p.8-9 RECENT YEARS ........................................................................................................................ p.10-22 A. From the establishment of Athens as capital city of the neo-Greek state until the end of 19th century. I. The first maps of Athens and the urban planning development II. The district of Metaxourgeion • Inclusion of the area in the plan of Kleanthis-Schaubert • The effect of the proposition of Klenze regarding the construction of the palace in Kerameikos • Consequences of the transfer of the palace to Syntagma square • The silk mill factory and the industrialization of the area • The crystallization of the mixed suburban character of the district B. 20th century I. The reformation projects