Nigeria Training Module on Gender Dimensions of Criminal Justice Responses to Terrorism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Criminogenic Patterns in the Management of Boko Haram's

Third World Quarterly ISSN: 0143-6597 (Print) 1360-2241 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/ctwq20 Criminogenic patterns in the management of Boko Haram’s human displacement situation Medinat A. Abdulazeez & Temitope B. Oriola To cite this article: Medinat A. Abdulazeez & Temitope B. Oriola (2018) Criminogenic patterns in the management of Boko Haram’s human displacement situation, Third World Quarterly, 39:1, 85-103, DOI: 10.1080/01436597.2017.1369028 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2017.1369028 Published online: 14 Sep 2017. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 204 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=ctwq20 THIRD WORLD QUARTERLY, 2018 VOL. 39, NO. 1, 85–103 https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2017.1369028 Criminogenic patterns in the management of Boko Haram’s human displacement situation Medinat A. Abdulazeeza and Temitope B. Oriolab aDepartment of History and International Studies, Nigerian Defence Academy, Kaduna, Nigeria; bDepartment of Sociology, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Canada ABSTRACT ARTICLE HISTORY This article interrogates the management of the internal displacement Received 22 December 2016 caused by the activities of Boko Haram in Nigeria. The study utilizes Accepted 15 August 2017 qualitative methods to explicate the lived realities of internally KEYWORDS displaced persons (IDPs) at three IDP camps. It accentuates the Boko Haram invention of criminogenic patterns that have fostered several state terrorism crimes in the management of the displacement situation. A series human displacement of cyclical patterns is highlighted: these patterns are constituted by Internally Displaced Persons and constitutive of the social conditions of the IDPs. -

Social Media in Africa

Social media in Africa A double-edged sword for security and development Technical annex Kate Cox, William Marcellino, Jacopo Bellasio, Antonia Ward, Katerina Galai, Sofia Meranto, Giacomo Persi Paoli Table of contents Table of contents ...................................................................................................................................... iii List of figures ........................................................................................................................................... iv List of tables .............................................................................................................................................. v Abbreviations .......................................................................................................................................... vii Annex A: Overview of Technical Annex .................................................................................................... 1 Annex B: Background to al-Shabaab, Boko Haram and ISIL ..................................................................... 3 Annex C: Timeline of significant dates ...................................................................................................... 9 Annex D: Country profiles ...................................................................................................................... 25 Annex E: Social media and communications platforms ............................................................................ 31 Annex F: Twitter data -

Rapid Protection Assessment Report (Borno PSWG)

Rapid Protection Assessment Report Borno State, Nigeria IN PARTNERSHIP WITH 1 | Page OBJECTIVE The Borno PSWG Rapid Protection Due to the opening up of limited humanitarian Assessment Report compiles information from accessibility in areas formerly under Boko both data collection in IDP sites around Haram control, the need for a rapid protection Maiduguri (Part I) as well as in recently assessment in Dikwa and Damboa was liberated satellite camps of Damboa and urgently raised. The assessment objective Dikwa (Part II). was to identify pressing protection concerns in the satellite IDP camps to inform immediate The assessment of displacement sites around interventions to the most vulnerable, a rapid Maiduguri Metropolis (MMC, Jere, Konduga) Central Emergency Response Fund (CERF) was conducted in order to obtain a full picture response, as well as to promote access, of protection issues and severity in all sites dignity and accountability to displaced around Maiduguri in order to prioritize the most currently experiencing the most severe of pressing issues and severe sites, for targeted circumstances. rapid interventions. “This is not your place, this is our place.” IDPs in Jidumuri recount what host community members tell them 2 | Page PART I: RAPID PROTECTION ASSESSMENT IN IDP SITES AROUND MAIDUGURI OVERVIEW A rapid protection assessment was conducted by PSWG has only targeted specific IDP camps (such as Bakassi, Borno, led by UNHCR, from May 10-14, 2016 in Maiduguri Dalori and NYSC) and that other camps and host Metropolis (Maiduguri, Jere and Konduga LGAs) with the communities in general were being largely overlooked by view to identify protection issues at the community-level in humanitarians. -

UNHCR Monthly Update October 2016

October 2016 ISSUE # 7 NIGERIA: MONTHLY UPDATE UNHCR IDP operation achievements for January through October 2016 Breakdown of individuals reached REACHED 505,750 147,036 117,160 138,563 102,991 individuals reached by UNHCR from Jan - Oct 2016 Girls Boys Women Men # of vulnerable IDPs individually screened 157,780 52% CHILDREN # of vulnerable individuals provided with material protection-based assistance 154,986 of the individuals reached are boys and girls # of returning refugees individually registered 143,848 # of individuals receiving emergency shelter 22,206 # of persons reached through awareness raising and community-based 43% 57% initiatives 16,193 Male Female # of persons trained in core Protection services (Peacebuilding, CCCM, 3,206 mainstreaming) # of individuals identified through protection monitoring and provided with 2,695 response, including through referrals for appropriate specialized services Total reached INTERVENTIONS by state # of vulnerable persons provided with livelihood support 2,140 13 Total reached by LGA 7 - 3,000 # of survivors of SGBV provided with comprehensive specialized services, core UNHCR IDP operations in 76 Local including psychosocial support to promote their wellbeing 1,367 Government Area in 6 states 3,001 - 12,000 (Access to Justice, Advocacy, Capacity Building, Coordination (Protection,ES/NFI/CCCM), 12,000 - 24,000 # of vulnerable persons provided with access to justice 1,329 Emergency Shelter, Livelihood, Peacebuilding, Protection Monitoring and Response, Protection-based Material Assistance, -

How Boko Haram Specifically Targets Displaced People

POLICY BRIEF How Boko Haram specifically targets displaced people Aimée-Noël Mbiyozo Since 2009, Boko Haram has proven to be a highly adaptable foe, routinely realigning its tactics to suit changing circumstances. In recent years, this has increasingly involved focusing on soft targets, including displaced people (both refugees and internally displaced people). Understanding how Boko Haram has targeted displaced people and what some of its specific objectives might be is key to understanding their true threat. Limitations Key points This brief should not be read as a comprehensive analysis of Boko Haram Countries have established that behaviour. Summaries of Boko Haram activities are provided using available they view mass migrant flows evidence to establish a trend of increased activity targeting displaced people as a growing issue. Extremist (including refugees and internally displaced people). Other ISS documents groups’ unique ability to control and authors are available for more thorough understanding of Boko Haram. these flows may become increasingly valuable to these Boko Haram’s growing focus on ‘soft’ targets groups, as it could strengthen their bargaining positions. In 2016, the Global Terrorism Index labelled Boko Haram the world’s second- deadliest terrorist group, down from its position as the most deadly in 2015.1 Boko Haram could be Since 2009, when the group launched its violent campaign, its reign of terror strategically generating has resulted in the deaths of more than 20 000 people and displaced more migration to overwhelm than 2 million throughout Nigeria, and has spread across northeast Nigeria governments in an attempt into Cameroon, Niger and Chad.2 to force them to submit to its demands. -

Older People's Experience of Conflict, Displacement, and Detention In

“MY HEART IS IN PAIN” OLDER PEOPLE’S EXPERIENCE OF CONFLICT, DISPLACEMENT, AND DETENTION IN NORTHEAST NIGERIA Amnesty International is a movement of 10 million people which mobilizes the humanity in everyone and campaigns for change so we can all enjoy our human rights. Our vision is of a world where those in power keep their promises, respect international law and are held to account. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and individual donations. We believe that acting in solidarity and compassion with people everywhere can change our societies for the better. Cover photo: Shakwa, around 90 years old, sits against her shelter in an IDP camp in Borno State, © Amnesty International 2020 Nigeria, October 2020. © The Walking Paradox / Amnesty International. Except where otherwise noted, content in this document is licensed under a Creative Commons (attribution, non-commercial, no derivatives, international 4.0) licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode For more information please visit the permissions page on our website: www.amnesty.org Where material is attributed to a copyright owner other than Amnesty International this material is not subject to the Creative Commons licence. First published in 2020 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House, 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW, UK Index: AFR 44/3376/2020 Original language: English amnesty.org CONTENTS MAP 4 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 5 METHODOLOGY 11 1. BACKGROUND 13 1.1 CONFLICT, DISPLACEMENT, AND IMPUNITY 13 1.2 OLDER PEOPLE IN SITUATIONS OF CRISIS 15 2. BOKO HARAM’S CRIMES 20 2.1 MURDER AND TORTURE 21 2.2 MURDER AND ABDUCTION OF CHILDREN 24 2.3 BEATINGS AND DENIAL OF OLDER WOMEN’S LIVELIHOOD 25 2.4 LOOTING, EXTREME FOOD INSECURITY 26 2.5 CHALLENGES OF FLEEING 27 3. -

Beyond Chibok Over 1.3 Million Children Uprooted by Boko Haram Violence

Beyond Chibok Over 1.3 million children uprooted by Boko Haram violence On 14 April 2014, over 270 schoolgirls were abducted in the town of Chibok, North-East Nigeria. The world was shocked. A global movement started demanding their return. #BringBackOurGirls Since then, at least 1.3 million children have been uprooted by Boko Haram violence across four countries in the Lake Chad region. The world barely noticed. #BringBackOurChildhood UNICEF Chad/2015/Laurent Duvillier Since the Chibok girls’ abduction two years ago, countries, children are killed, maimed, abducted thousands of other children have disappeared in and recruited to armed groups. They are exposed Cameroon, Chad, Niger and Nigeria. to sexual violence, schools are attacked and humanitarian access is limited. Scores have been separated from their families and subjected to exploitation, abuse and Hit-and-run attacks and suicide bombings recruitment by armed groups. Some have even are depriving people of essential services, been used to carry out suicide bombings. Yet, destroying vital infrastructure and sowing fear. their stories are barely told. In North-East Nigeria, about 90 per cent of displaced families are sheltered by some of the world’s poorest communities, placing additional strain on already limited resources. The Boko Haram insurgency has triggered the displacement of 2.3 million people since May Boys are forced to attack their own families to 2013. In just one year, the number of displaced demonstrate their loyalty to Boko Haram, while children increased by over 60 per cent, from girls are exposed to severe abuse including 800,000 to 1.3 million children. -

The Implication of Boko Haram Insurgency on Women and Girls in North East Nigeria

Journal of Public Administration and Social Welfare Research Vol. 4 No. 1 2019 ISSN 2504-3597 www.iiardpub.org The Implication of Boko Haram Insurgency on Women and Girls in North East Nigeria Abinoam Abdu Research Fellow, Centre for Peace, Diplomatic and Development Studies (CPDDS), University of Maiduguri. [email protected], [email protected] Samaila Simon Shehu History Department, University of Maiduguri. [email protected] Abstract This study is set out to make a historical analysis and examination of the implications of Boko Haram insurgency in the North East of Nigeria. The study will cover the period from the outbreak of the insurgency which was 2009, and up to 2017. The purpose of the study is to bring to limelight how the most vulnerable group in the society, women and girls, bears the brunt of the insurgency. The implications of Boko Haram insurgency on women and girls are diverse and dynamic in nature. While most of the impacts are negative, some are positive in nature. With regard to the former, many women and girls were abducted, enslaved and some were forced to join the group as fighters, e.g. female suicide bombers. Forced marriage was also imposed on some of them. Some women became widows while others are IDPs. Women and girls in the IDPs camps and some host communities were also faced with the challenge of insecurity, gender based violence and inadequate feeding which exposed them to malnutrition. With respect to the positive impacts, some young women join the Civilian Joint Task Force (CJTF) in fighting Boko Haram and also in frisking females at check points. -

En En Motion for a Resolution

European Parliament 2014-2019 Plenary sitting B8-1024/2015 6.10.2015 MOTION FOR A RESOLUTION with request for inclusion in the agenda for a debate on cases of breaches of human rights, democracy and the rule of law pursuant to Rule 135 of the Rules of Procedure on the mass displacement of children in Nigeria as a result of Boko Haram attacks (2015/2876(RSP)) Josef Weidenholzer, Ana Gomes, Alessia Maria Mosca, Victor Boştinaru, Elena Valenciano, Richard Howitt, Afzal Khan, Norbert Neuser, Pier Antonio Panzeri, Eric Andrieu, Nikos Androulakis, Zigmantas Balčytis, Hugues Bayet, Brando Benifei, Goffredo Maria Bettini, José Blanco López, Vilija Blinkevičiūtė, Simona Bonafè, Biljana Borzan, Nicola Caputo, Andrea Cozzolino, Andi Cristea, Viorica Dăncilă, Nicola Danti, Isabella De Monte, Jonás Fernández, Monika Flašíková Beňová, Eugen Freund, Doru-Claudian Frunzulică, Eider Gardiazabal Rubial, Enrico Gasbarra, Elena Gentile, Lidia Joanna Geringer de Oedenberg, Neena Gill, Michela Giuffrida, Maria Grapini, Theresa Griffin, Roberto Gualtieri, Sylvie Guillaume, Sergio Gutiérrez Prieto, Anna Hedh, Cătălin Sorin Ivan, Liisa Jaakonsaari, Jude Kirton-Darling, Jeppe Kofod, Javi López, Olle Ludvigsson, Krystyna Łybacka, Andrejs Mamikins, Louis- Joseph Manscour, David Martin, Csaba Molnár, Victor Negrescu, Momchil Nekov, Jens Nilsson, Demetris Papadakis, Vincent Peillon, Tonino Picula, Miroslav Poche, Inmaculada Rodríguez-Piñero Fernández, Daciana Octavia Sârbu, Olga Sehnalová, Siôn Simon, Tibor Szanyi, RE\P8_B(2015)1024_EN.doc PE568.511v01-00 EN United -

Nigerian Terror: the Rise of Boko Haram Kelly Moss James Madison University

James Madison University JMU Scholarly Commons Senior Honors Projects, 2010-current Honors College Spring 2018 Nigerian terror: The rise of Boko Haram Kelly Moss James Madison University Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/honors201019 Part of the International Relations Commons Recommended Citation Moss, Kelly, "Nigerian terror: The rise of Boko Haram" (2018). Senior Honors Projects, 2010-current. 607. https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/honors201019/607 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors College at JMU Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Honors Projects, 2010-current by an authorized administrator of JMU Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Nigerian Terror: The Rise of Boko Haram _______________________ An Honors Program Project Presented to the Faculty of the Undergraduate College of Arts and Letters James Madison University _______________________ by Kelly Moss Spring 2018 Accepted by the faculty of the Department of Political Science, James Madison University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Honors Program. FACULTY COMMITTEE: Project Advisor: Kerry Crawford, Ph.D., Bradley R. Newcomer, Ph.D., Associate Professor, Political Science Director, Honors Program Reader: David Owusu-Ansah, Ph.D., Professor, History Reader: Glenn Hastedt, Ph.D., Chair, Justice Studies PUBLIC PRESENTATION This work is accepted for presentation, in part or in full, at Miller Hall on April 17, 2018. HONORS COLLEGE APPROVAL: 2 Table of Contents I. Abstract……………………………………………………………………........ 3 II. Dedication…………………………………………………………………….... 4 III. Acknowledgements…………………………………………………………….. 5 IV. List of Figures………………………………………………………………….. 6 V. Chapter 1: Introduction……………………………………………………........ 7 VI. Chapter 2: The Rise…………………………………………………………… 33 VII. -

Nigeria: “We Dried Our Tears”

“WE DRIED OUR TEARS” ADDRESSING THE TOLL ON CHILDREN OF NORTHEAST NIGERIA’S CONFLICT Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 7 million people who campaign for a world where human rights are enjoyed by all. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. © Amnesty International 2020 Except where otherwise noted, content in this document is licensed under a Creative Commons Cover photo: A girl sits beside cooking utensils near a school burnt in a camp for internally displaced (attribution, non-commercial, no derivatives, international 4.0) licence. people in the Monguno local government area of Borno State, Nigeria, 14 February 2017. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode © FLORIAN PLAUCHEUR/AFP via Getty Images For more information please visit the permissions page on our website: www.amnesty.org Where material is attributed to a copyright owner other than Amnesty International this material is not subject to the Creative Commons licence. First published in 2020 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House, 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW, UK Index: AFR 44/2322/2020 Original language: English amnesty.org CONTENTS MAP 5 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 6 METHODOLOGY 11 1. BACKGROUND 14 1.1 CONFLICT IN NORTHEAST NIGERIA 14 1.2 ACCOUNTABILITY 15 1.3 CHILDREN AND ARMED CONFLICT 16 2. BOKO HARAM ABUSES 20 2.1 WIDESPREAD ABDUCTIONS 21 2.2 CHILD SOLDIERS AND “WIVES” 24 2.3 FORCED TO WITNESS AND COMMIT ATROCITIES 26 2.4 PILLAGE AND OTHER ATTACKS ON FOOD SECURITY 28 2.5 PUNISH, KILL THOSE WHO FLEE 29 2.6 ATTACKS ON SCHOOLS AND TEACHERS 31 2.7 ASSAULT ON CHILDHOOD 32 3. -

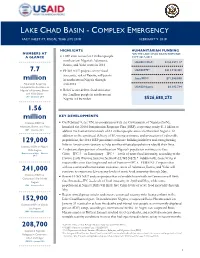

Lake Chad Basin Complex Emergency Fact Sheet #7

LAKE CHAD BASIN - COMPLEX EMERGENCY FACT SHEET #7, FISCAL YEAR (FY) 2018 FEBRUARY 9, 2018 HIGHLIGHTS HUMANITARIAN FUNDING NUMBERS AT FOR THE LAKE CHAD BASIN RESPONSE A GLANCE HRP aims to reach 6.1 million people IN FY 2017–2018 northeastern Nigeria’s Adamawa, USAID/OFDA1 $134,497,117 Borno, and Yobe states in 2018 7.7 FEWS NET projects severe food USAID/FFP2 3 $314,910,422 insecurity, risk of Famine will persist 3 million in northeastern Nigeria through State/PRM $71,090,000 Population Requiring mid-2018 Humanitarian Assistance in USAID/Nigeria $6,182,734 Nigeria’s Adamawa, Borno, Relief actors deliver food assistance and Yobe States for 2 million people in northeastern UN – December 2017 Nigeria in December $526,680,273 1.56 million KEY DEVELOPMENTS Estimated IDPs in On February 8, the UN, in coordination with the Government of Nigeria (GoN), Adamawa, Borno, and Yobe launched the 2018 Humanitarian Response Plan (HRP), requesting nearly $1.1 billion to IOM – December 2017 address the humanitarian needs of 6.1 million people across northeastern Nigeria. In addition to the continued delivery of life-saving assistance and protection of vulnerable 129,000 populations, the 2018 HRP prioritizes resilience-building initiatives and strengthening links to longer-term recovery to help conflict-affected populations rebuild their lives. Estimated IDPs in Niger’s Diffa Region A substantial proportion of northeastern Nigeria’s population continues to face Government of Niger – October Crisis—IPC 3—or Emergency—IPC 4—levels of acute food insecurity, according to the 2017 Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS NET).4 Additionally, those living in inaccessible areas face heightened risk of Famine—IPC 5.