Arxiv:0901.3958V2 [Hep-Ph] 29 Jan 2009 Eul Rkn SU(2) Broken, Neously Information

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Quantum Field Theory*

Quantum Field Theory y Frank Wilczek Institute for Advanced Study, School of Natural Science, Olden Lane, Princeton, NJ 08540 I discuss the general principles underlying quantum eld theory, and attempt to identify its most profound consequences. The deep est of these consequences result from the in nite number of degrees of freedom invoked to implement lo cality.Imention a few of its most striking successes, b oth achieved and prosp ective. Possible limitation s of quantum eld theory are viewed in the light of its history. I. SURVEY Quantum eld theory is the framework in which the regnant theories of the electroweak and strong interactions, which together form the Standard Mo del, are formulated. Quantum electro dynamics (QED), b esides providing a com- plete foundation for atomic physics and chemistry, has supp orted calculations of physical quantities with unparalleled precision. The exp erimentally measured value of the magnetic dip ole moment of the muon, 11 (g 2) = 233 184 600 (1680) 10 ; (1) exp: for example, should b e compared with the theoretical prediction 11 (g 2) = 233 183 478 (308) 10 : (2) theor: In quantum chromo dynamics (QCD) we cannot, for the forseeable future, aspire to to comparable accuracy.Yet QCD provides di erent, and at least equally impressive, evidence for the validity of the basic principles of quantum eld theory. Indeed, b ecause in QCD the interactions are stronger, QCD manifests a wider variety of phenomena characteristic of quantum eld theory. These include esp ecially running of the e ective coupling with distance or energy scale and the phenomenon of con nement. -

Weak Interaction Processes: Which Quantum Information Is Revealed?

Weak Interaction Processes: Which Quantum Information is revealed? B. C. Hiesmayr1 1University of Vienna, Faculty of Physics, Boltzmanngasse 5, 1090 Vienna, Austria We analyze the achievable limits of the quantum information processing of the weak interaction revealed by hyperons with spin. We find that the weak decay process corresponds to an interferometric device with a fixed visibility and fixed phase difference for each hyperon. Nature chooses rather low visibilities expressing a preference to parity conserving or violating processes (except for the decay Σ+ pπ0). The decay process can be considered as an open quantum channel that carries the information of the−→ hyperon spin to the angular distribution of the momentum of the daughter particles. We find a simple geometrical information theoretic 1 α interpretation of this process: two quantization axes are chosen spontaneously with probabilities ±2 where α is proportional to the visibility times the real part of the phase shift. Differently stated the weak interaction process corresponds to spin measurements with an imperfect Stern-Gerlach apparatus. Equipped with this information theoretic insight we show how entanglement can be measured in these systems and why Bell’s nonlocality (in contradiction to common misconception in literature) cannot be revealed in hyperon decays. We study also under which circumstances contextuality can be revealed. PACS numbers: 03.67.-a, 14.20.Jn, 03.65.Ud Weak interactions are one out of the four fundamental in- systems. teractions that we think that rules our universe. The weak in- Information theoretic content of an interfering and de- teraction is the only interaction that breaks the parity symme- caying system: Let us start by assuming that the initial state try and the combined charge-conjugation–parity( P) symme- of a decaying hyperon is in a separable state between momen- C try. -

1 Drawing Feynman Diagrams

1 Drawing Feynman Diagrams 1. A fermion (quark, lepton, neutrino) is drawn by a straight line with an arrow pointing to the left: f f 2. An antifermion is drawn by a straight line with an arrow pointing to the right: f f 3. A photon or W ±, Z0 boson is drawn by a wavy line: γ W ±;Z0 4. A gluon is drawn by a curled line: g 5. The emission of a photon from a lepton or a quark doesn’t change the fermion: γ l; q l; q But a photon cannot be emitted from a neutrino: γ ν ν 6. The emission of a W ± from a fermion changes the flavour of the fermion in the following way: − − − 2 Q = −1 e µ τ u c t Q = + 3 1 Q = 0 νe νµ ντ d s b Q = − 3 But for quarks, we have an additional mixing between families: u c t d s b This means that when emitting a W ±, an u quark for example will mostly change into a d quark, but it has a small chance to change into a s quark instead, and an even smaller chance to change into a b quark. Similarly, a c will mostly change into a s quark, but has small chances of changing into an u or b. Note that there is no horizontal mixing, i.e. an u never changes into a c quark! In practice, we will limit ourselves to the light quarks (u; d; s): 1 DRAWING FEYNMAN DIAGRAMS 2 u d s Some examples for diagrams emitting a W ±: W − W + e− νe u d And using quark mixing: W + u s To know the sign of the W -boson, we use charge conservation: the sum of the charges at the left hand side must equal the sum of the charges at the right hand side. -

Introduction to Supersymmetry

Introduction to Supersymmetry Pre-SUSY Summer School Corpus Christi, Texas May 15-18, 2019 Stephen P. Martin Northern Illinois University [email protected] 1 Topics: Why: Motivation for supersymmetry (SUSY) • What: SUSY Lagrangians, SUSY breaking and the Minimal • Supersymmetric Standard Model, superpartner decays Who: Sorry, not covered. • For some more details and a slightly better attempt at proper referencing: A supersymmetry primer, hep-ph/9709356, version 7, January 2016 • TASI 2011 lectures notes: two-component fermion notation and • supersymmetry, arXiv:1205.4076. If you find corrections, please do let me know! 2 Lecture 1: Motivation and Introduction to Supersymmetry Motivation: The Hierarchy Problem • Supermultiplets • Particle content of the Minimal Supersymmetric Standard Model • (MSSM) Need for “soft” breaking of supersymmetry • The Wess-Zumino Model • 3 People have cited many reasons why extensions of the Standard Model might involve supersymmetry (SUSY). Some of them are: A possible cold dark matter particle • A light Higgs boson, M = 125 GeV • h Unification of gauge couplings • Mathematical elegance, beauty • ⋆ “What does that even mean? No such thing!” – Some modern pundits ⋆ “We beg to differ.” – Einstein, Dirac, . However, for me, the single compelling reason is: The Hierarchy Problem • 4 An analogy: Coulomb self-energy correction to the electron’s mass A point-like electron would have an infinite classical electrostatic energy. Instead, suppose the electron is a solid sphere of uniform charge density and radius R. An undergraduate problem gives: 3e2 ∆ECoulomb = 20πǫ0R 2 Interpreting this as a correction ∆me = ∆ECoulomb/c to the electron mass: 15 0.86 10− meters m = m + (1 MeV/c2) × . -

Supersymmetry Min Raj Lamsal Department of Physics, Prithvi Narayan Campus, Pokhara Min [email protected]

Supersymmetry Min Raj Lamsal Department of Physics, Prithvi Narayan Campus, Pokhara [email protected] Abstract : This article deals with the introduction of supersymmetry as the latest and most emerging burning issue for the explanation of nature including elementary particles as well as the universe. Supersymmetry is a conjectured symmetry of space and time. It has been a very popular idea among theoretical physicists. It is nearly an article of faith among elementary-particle physicists that the four fundamental physical forces in nature ultimately derive from a single force. For years scientists have tried to construct a Grand Unified Theory showing this basic unity. Physicists have already unified the electron-magnetic and weak forces in an 'electroweak' theory, and recent work has focused on trying to include the strong force. Gravity is much harder to handle, but work continues on that, as well. In the world of everyday experience, the strengths of the forces are very different, leading physicists to conclude that their convergence could occur only at very high energies, such as those existing in the earliest moments of the universe, just after the Big Bang. Keywords: standard model, grand unified theories, theory of everything, superpartner, higgs boson, neutrino oscillation. 1. INTRODUCTION unifies the weak and electromagnetic forces. The What is the world made of? What are the most basic idea is that the mass difference between photons fundamental constituents of matter? We still do not having zero mass and the weak bosons makes the have anything that could be a final answer, but we electromagnetic and weak interactions behave quite have come a long way. -

Spontaneous Symmetry Breaking in the Higgs Mechanism

Spontaneous symmetry breaking in the Higgs mechanism August 2012 Abstract The Higgs mechanism is very powerful: it furnishes a description of the elec- troweak theory in the Standard Model which has a convincing experimental ver- ification. But although the Higgs mechanism had been applied successfully, the conceptual background is not clear. The Higgs mechanism is often presented as spontaneous breaking of a local gauge symmetry. But a local gauge symmetry is rooted in redundancy of description: gauge transformations connect states that cannot be physically distinguished. A gauge symmetry is therefore not a sym- metry of nature, but of our description of nature. The spontaneous breaking of such a symmetry cannot be expected to have physical e↵ects since asymmetries are not reflected in the physics. If spontaneous gauge symmetry breaking cannot have physical e↵ects, this causes conceptual problems for the Higgs mechanism, if taken to be described as spontaneous gauge symmetry breaking. In a gauge invariant theory, gauge fixing is necessary to retrieve the physics from the theory. This means that also in a theory with spontaneous gauge sym- metry breaking, a gauge should be fixed. But gauge fixing itself breaks the gauge symmetry, and thereby obscures the spontaneous breaking of the symmetry. It suggests that spontaneous gauge symmetry breaking is not part of the physics, but an unphysical artifact of the redundancy in description. However, the Higgs mechanism can be formulated in a gauge independent way, without spontaneous symmetry breaking. The same outcome as in the account with spontaneous symmetry breaking is obtained. It is concluded that even though spontaneous gauge symmetry breaking cannot have physical consequences, the Higgs mechanism is not in conceptual danger. -

The Three Jewels in the Crown of The

The three jewels in the crown of the LHC Yosef Nir Department of Particle Physics and Astrophysics, Weizmann Institute of Science, Rehovot 7610001, Israel [email protected] Abstract The ATLAS and CMS experiments have made three major discoveries: The discovery of an elementary spin-zero particle, the discovery of the mechanism that makes the weak interactions short-range, and the discovery of the mechanism that gives the third generation fermions their masses. I explain how this progress in our understanding of the basic laws of Nature was achieved. arXiv:2010.13126v1 [hep-ph] 25 Oct 2020 It is often stated that the Higgs discovery is “the jewel in the crown” of the ATLAS/CMS research. We would like to argue that ATLAS/CMS made (at least) three major discoveries, each of deep significance to our understanding of the basic laws of Nature: 1. The discovery of an elementary spin-0 particle, the first and only particle of this type to have been discovered. 2. The discovery of the mechanism that makes the weak interactions short-ranged, in contrast to the other (electromagnetic and strong) interactions mediated by spin-1 particles. 3. The discovery of the mechanism that gives masses to the three heaviest matter (spin- 1/2) particles, through a unique type of interactions. These three breakthrough discoveries can be related, in one-to-one correspondence, to three distinct classes of measurements: 1. The Higgs boson decay into two photons. 2. The Higgs boson decay into a W - or a Z-boson and a fermion pair, and the Higgs production via vector boson (W W or ZZ) fusion. -

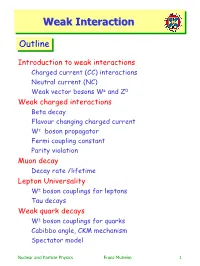

Weak Interactioninteraction

WeakWeak InteractionInteraction OutlineOutline Introduction to weak interactions Charged current (CC) interactions Neutral current (NC) Weak vector bosons W± and Z0 Weak charged interactions Beta decay Flavour changing charged current W± boson propagator Fermi coupling constant Parity violation Muon decay Decay rate /lifetime Lepton Universality W± boson couplings for leptons Tau decays Weak quark decays W± boson couplings for quarks Cabibbo angle, CKM mechanism Spectator model Nuclear and Particle Physics Franz Muheim 1 IntroductionIntroduction Weak Interactions Account for large variety of physical processes Muon and Tau decays, Neutrino interactions Decays of lightest mesons and baryons Z0 and W± boson production at √s ~ O(100 GeV) Natural radioactivity, fission, fusion (sun) Major Characteristics Long lifetimes Small cross sections (not always) “Quantum Flavour Dynamics” Charged Current (CC) Neutral Current (NC) mediated by exchange of W± boson Z0 boson Intermediate vector bosons MW = 80.4 GeV ± 0 W and Z have mass MZ = 91.2 GeV Self Interactions of W± and Z0 also W± and γ Nuclear and Particle Physics Franz Muheim 2 BetaBeta DecayDecay Weak Nuclear Decays See also Nuclear Physics Recall β+ = e+ β- = e- Continuous energy spectrum of e- or e+ Î 3-body decay, Pauli postulates neutrino, 1930 Interpretation Fermi, 1932 Bound n or p decay − n → pe ν e ⎛ − t ⎞ N(t) = N(0)exp⎜ ⎟ ⎝ τ n ⎠ p → ne +ν (bound p) τ n = 885.7 ± 0.8 s e 32 τ 1 = τ n ln 2 = 613.9 ± 0.6 s τ p > 10 y (p stable) 2 Modern quark level picture Weak charged current mediated -

Beyond the Standard Model: Supersymmetry

Beyond the Standard Model: Supersymmetry • Outline – Why the Standard Model is probably not the final word – One way it might be fixed up: • Supersymmetry • What it is • What is predicts – How can we test it? A.J. Barr Preface • Standard Model doing very well – Measurements in agreement with predictions γ – Some very exact: electron dipole moment to 12 significant figures • However SM does not include: e e – Dark matter All QED contributions • Weakly interacting massive particles? to dipole moment with ≤ four loops – Gravity calculated • Not in SM at all – Grand Unification • Colour & Electroweak forces parts of one “Grand Unified” group? – Has a problem with Higgs boson mass ShouldShould expectexpect toto findfind newnew phenomenaphenomena atat highhigh energyenergy Higgs boson mass • Standard Model Higgs boson mass: 114 GeV < mH <~ 1 TeV Direct searches at “LEP” WW boson scattering partial e+e- collider wave amplitudes > 1 h W e- W Z0 e+ W W Experimental search “Probabilities > 1” (compare Fermi model of weak interaction) More on mH … Fit to lots of data Measured W mass depends on mH (including mW)… H W W W W emits & absorbs virtual Higgs boson changes propagator changes measured mW: 2 ∆ ∝ m H H mW mW ln 2 mW log dependence on mH … mH lighter than about 200 GeV HiggsHiggs massmass isis samesame orderorder asas W,W, ZZ bosonsbosons Corrections to Higgs Mass? H The top quark gets its mass λ by coupling to Higgs bosons t t t λλ Similar diagram leads to a change HH_ in the Higgs propagator t change in mH Integrate (2) up to loop momentum -

Spontaneous Symmetry Breaking

BROWN-HET-1555 The History of the Guralnik, Hagen and Kibble development of the Theory of Spontaneous Symmetry Breaking and Gauge Particles Gerald S. Guralnik1 Physics Department2. Brown University, Providence — RI. 02912 Abstract I discuss historical material about the beginning of the ideas of spontaneous symme- try breaking and particularly the role of the Guralnik, Hagen Kibble paper in this development. I do so adding a touch of some more modern ideas about the extended solution-space of quantum field theory resulting from the intrinsic nonlinearity of non- trivial interactions. Contents 1 Introduction 1 2 What was front-line theoretical particle physics like in the early 1960s? 2 3 A simplified introduction to the solutions and phases of quantum field theory 3 4 Examples of the Goldstone theorem 7 5 Gauge particles and zero mass 10 arXiv:0907.3466v1 [physics.hist-ph] 20 Jul 2009 6 General proof that the Goldstone theorem for gauge theories does not require physical massless particles 13 7 Explicit symmetry-breaking solution of scalar QED in leading order, show- ing formation of a massive vector meson 15 8 Our initial reactions to the EB and H papers 18 9 Reactions and thoughts after the release of the GHK paper 21 [email protected] 2http://www.het.brown.edu/ 1. Introduction 1 1 Introduction This paper is an extended version of a colloquium that I gave at Washington University in St. Louis during the Fall semester of 2001. But for minor changes, it corresponds to my recent article in IJMPA [1]. It contains a good deal of historical material about the beginning of the development of the ideas of spontaneous symmetry breaking as well as a touch of some more modern ideas about the extended solution-space (also called vacuum manifold or moduli space) of quantum field theory due to the intrinsic nonlinearity of non-trivial interactions [2, 3]. -

Supersymmetry: Theory

SLAC-PUB-7125 March, 1996 Supersymmetry: Theory MICHAEL E. PESKI$ Stanford Linear Accelerator Center Stanford University, Stanford, California 94309 USA ABSTRACT If supersymmetric particles are discovered at high-energy col- liders, what can we hope to learn about them? In principle, the properties of supersymmetric particles can give a window into the physics of grand unification, or of other aspects of interactions at very short distances. In this article, I sketch out a systematic pro- gram for the experimental study of supersymmetric particles and point out the essential role that e + e - linear colliders will play in this investigation. to appear in the proceedings of the International Workshop on Physics and Experiments with Linear Colliders Morioka, Iwate-ken, Japan, September 8-12, 1995 aWork supportedby the Department of Energy, contract DE-AC03-76SF00515. SUPERSYMMETRY: THEORY MICHAEL E. PESKIN Stanford Linear Accelerator Center, Stanford University Stanford, California 94309 USA If supersymmetric particles are discovered at high-energy colliders, what can we hope to learn about them? In principle, the properties of supersymmetric particles can give a window into the physics of grand unification, or of other aspects of interactions at very short distances. In this article, I sketch out a systematic program for the experimental study of supersymmetric particles and point out the essential role that e+e- linear colliders will play in this investigation. 1 Introduction When we think about the motivation for a future accelerator project, it is easy enough to work out its ability to continue ongoing experimental programs or to test with greater stringency well-understood theoretical models. -

Fermi's Theory of Weak Interactions

FERMI AND THE THEORY OF WEAK INTERACTIONS G. Rajasekaran Institute of Mathematical Sciences, Chennai 600113 and Chennai Mathematical Institute, Chennai 603103 e-mail: [email protected] Abstract The history of weak interactions starting with Fermi’s creation of the beta decay the- ory and culminating in its modern avatar in the form of the electroweak gauge theory is described. Discoveries of parity violation, matter-antimatter asymmetry, W and Z bosons and neutrino mass are highlighted. Introduction Sun gives us light and heat that makes life possible on the Earth. How do the Sun and stars produce energy and continue to shine for billions of years? Thermonuclear fusion is the answer as Eddington proposed in 1920 and Bethe demonstrated explicitly in 1939. Through a series of nuclear reactions, four protons (which are Hydrogen nuclei) in the core of the Sun combine to form a Helium nucleus emitting two positrons and two neutrinos and releasing 27 MeV of energy: 4 + + p + p + p + p He + e + e + νe + νe + 27MeV → This can be regarded as the most important reaction for all life, for without it there can be no life on Earth! The above reaction is caused by one of the basic forces of Nature, called weak interaction. Beta decays of nuclei and in fact the decays of most of the elementary particles are now known to be due to weak interaction. Enrico Fermi formulated the theory of weak interactions in 1934 and his theory has stood the ground very successfully with appropriate amendments and generalizations and finally served as a core part of the Standard Model of High Energy Physics, which is now known as the basis of almost ALL of Physics, except for gravitation.