A Second Look at What High School Students Who Are Blind Should Know About Technology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Development of Educational Materials

InSIDE: Including Students with Impairments in Distance Education Delivery Development of educational DEV2.1 materials Eleni Koustriava1, Konstantinos Papadopoulos1, Konstantinos Authors Charitakis1 Partner University of Macedonia (UOM)1, Johannes Kepler University (JKU) Work Package WP2: Adapted educational material Issue Date 31-05-2020 Report Status Final This project (598763-EPP-1-2018-1-EL-EPPKA2-CBHE- JP) has been co-funded by the Erasmus+ Programme of the European Commission. This publication [communication] reflects the views only of the authors, and the Commission cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein Project Partners University of National and Macedonia, Greece Kapodistrian University of Athens, Coordinator Greece Johannes Kepler University of Aboubekr University, Austria Belkaid Tlemcen, Algeria Mouloud Mammeri Blida 2 University, Algeria University of Tizi-Ouzou, Algeria University of Sciences Ibn Tofail university, and Technology of Oran Morocco Mohamed Boudiaf, Algeria Cadi Ayyad University of Sfax, Tunisia University, Morocco Abdelmalek Essaadi University of Tunis El University, Morocco Manar, Tunisia University of University of Sousse, Mohammed V in Tunisia Rabat, Morocco InSIDE project Page WP2: Adapted educational material 2018-3218 /001-001 [2|103] DEV2.1: Development of Educational Materials Project Information Project Number 598763-EPP-1-2018-1-EL-EPPKA2-CBHE-JP Grant Agreement 2018-3218 /001-001 Number Action code CBHE-JP Project Acronym InSIDE Project Title -

Supported Reading Software

Readers: Hardware & Software AMIS is a DAISY 2 & 3 playback software application for DTBs. Features include navigation by section, sub-section, page, and phrase; bookmarking; customize font, color; control voice rate and volume; navigation shortcuts; two views. http://www.daisy.org/amis?q=project/amis Balabolka is a text-to-speech (TTS) program. All computer voices installed on a system are available to Balabolka. On-screen text can be saved as a WAV, MP3, OGG or WMA file. The program can read clipboard content, view text from DOC, RTF, PDF, FB2 and HTML files, customize font and background color, control reading from the system tray or by global hotkeys. It can also be run from a flash drive. http://www.cross-plus- a.com/balabolka.htm BeBook offers four stand-alone e-book reader devices, from a mini model with a 5" screen to a wireless model with Wi-Fi capability. BeBook supports over 20 file formats, including Word, ePUB, PDF, Text, Mobipocket, HTML, JPG, and MP3. It has a patented Vizplex screen and 512 MB internal memory (which can store over 1,000 books) while external memory can be used with an SD card. Features include the ability to adjust fonts and font sizes, bookmarking, 9 levels of magnification with PDF sources, and menu support in 15 languages. http://mybebook.com/ Blio “is a reading application that presents e-books just like the printed version, in full color … with …features” and allows purchased books to be used on up to 5 devices with “reading views, including text-only mode, single page, dual page, tiled pages, or 3D ‘book view’” (from the web site). -

Using Extron Streaming Content Manager: a Help File

Help Using Extron Streaming Content Manager 79-584-101 Rev. C 11 15 Contents Prerequisites 5 System and Web Browser Requirements 5 Web Browser Requirements 5 About Streaming Content Manager 7 About Streaming Content Manager 7 General Product Overview 7 What SCM Does 7 Signal Flow Within Streaming Content Manager 8 User Roles 9 Comparing User Types Based on Origin (Local or AD Accounts) 13 How to Find Information About SCM 14 Getting Started 16 Opening Streaming Content Manager 16 Logging In and Logging Out 17 Overview of the SCM Software Interface 19 How the SCM Web Pages Are Organized 19 Managing User Accounts 22 Editing My Profile 22 Resetting or Changing Your Password 26 Guidelines for Passwords 26 Resetting a Forgotten Password 27 Changing an Existing Password 28 Managing Recordings 31 Managing Recordings: an Overview 31 Locating and Accessing Recordings 32 About The Recordings Pages 32 List View Pages and Their Corresponding Tabs: What Content Appears on Which Page 33 Detail View Pages 34 Player Pages 35 Using Streaming Content Manager (SCM) Software • Contents 2 Locating Recordings in a List 36 Elements of Recording Entries 38 Elements of a Recording Entry in a List View 38 Elements of a Recording Entry in a Detail View 40 Recording Privacy Settings 41 Privacy Settings Defined 41 Default Privacy Setting 42 Privacy Settings and Unauthenticated Users 42 Downloading a Recording Package 42 Why Download a Recording? 42 What Is In The Recording Package? 43 How to Download a Recording 43 Sharing a Recording 44 Editing Recording Details -

Intro to Various Aspects of Low Vision We

Outline & Index Introduction Computer Settings for Low Vision Low Vision Gateway - Intro to various aspects of Low Vision Websites with Useful Advice for the Visually Challenged Local Services for those with Low Vision Transportation & Low Vision Catalogs for Low Vision Products Proper Nutrition, Proper Eyecare Optical Magnifiers Cell Phones AudioBooks & eBooks eBook Readers Low Vision Magazines & Newsletters Low Vision Blogs & User Groups Assistive Technology Magnifiers, Electronic, Hand Held Magnifiers, Electronic, Desktop (CCTV) Magnifier Software for the Computer Screen Magnifiers for the Web Browser Low Vision Web Browsers Text to Speech Screen Readers, Software for Computers Scan to Speech Conversion Speech to Text Conversion, Speech Recognition The Macintosh The Apple Macintosh & its Special Strengths Mac Universal Access Commands Magnifiers for the Macintosh Text to Speech Screen Readers for Macintoshes Speech Recognition for Macs Financial Aid for Assistive Technology AudioBooks & eBooks Audiobooks are read to you by a recorded actor. eBooks allow you to download the book, magnify the type size and have the computer read to you out loud. Free Online eBooks • Online Books http://onlinebooks.library.upenn.edu/ • Gutenberg Project http://www.gutenberg.net/index.php • Net Library – 24,000 eBooks & 2,000 eAudiobooks. Sign up thru your public library, then sign on to NC Live, and finally to Net Library. http://netlibrary.com/Centers/AudiobookCenter/Browse .aspx?Category=Lectures Free Online Audiobooks • http://librivox.org/newcatalog/search.php?title=&aut hor=&status=complete&action=Search • http://www.audiobooksforfree.com/ Books on CD & cassette North Carolina Library for the Blind (see above) http://statelibrary.dcr.state.nc.us/lbph/lbph.htm Downloadable Talking Books for the Blind https://www.nlstalkingbooks.org/dtb/ Audible.com. -

Infobase Professional Development and Training Platform

INFOBASE PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT AND TRAINING PLATFORM Course List 1 Infobase Professional Development & Training Platform Integration Instructional StrategiesStudent Resources Professional Responsibility/ Digital LiteracyTechnology Special Populations Software & Technology Communication Course Title (Un)Limiting Practices for Adolescent English Learners x with Limited or Interrupted Formal Schooling 21st Century Skills Concepts x 3D Dreams x 5 Minutes to Success x A Brief Overview of a 1:1 Classroom Training x x A Day with Beauford Cat x A Digitally Accessible Campus x A Frog's Life: Sequence It! x A Quick Look at Apps for x x About Me x Academic Integrity x x Access 2007 - Advanced Training x Access 2007 - Intermediate Training x Access 2007 - Intro Training x Access 2010 - Advanced Training x Access 2010 - Intermediate Training x Access 2010 - Intro Training x Access 2013 Training x Access 2016 x Accessibility: It IS Important x x Accessible Online Course x Acrobat Pro 9 - Accessibility Features Training x x Acrobat Pro 9 - Intro Training x Acrobat Pro DC x Acrobat Pro XI - Accessibility Features Training x x Acrobat Reader Training x Acrobat X Pro Training x Acrobat XI Pro Training x ActionScript 3 - Mobile Basics x Active Supervision x ActivInspire 1.7 - What's New? Training x x ActivInspire 1.8 Training x x ActivInspire Pro - Primary Interface Training x x ActivInspire Pro - Studio Interface Training x x ActivInspire Pro 1.3 - Primary Interface Training x x ActivPrimary 3 Training x x 2 www.Infobase.com • [email protected] Infobase -

Assistive Technology Guidelines: Grades 3-5 Updated 04.20.2020 01 Assistive Technology Guidelines Protocol

Michigan Assistive Technology Guidelines for Teachers of Students Who Are Blind or Visually Impaired Low Incidence Outreach 702 W. Kalamazoo St. Grades 3-5 Lansing, MI 48915 www.mdelio.org Updated 04.20.2020 State Board of Education Michelle Fecteau, Secretary Tom McMillin, Treasurer Judith Pritchett Pamela Pugh, Vice President Lupe Ramos-Montigny Nikki Snyder Tiffany Tilley, NASBE Delegate Casandra E. Ulbrich, President Marilyn Schneider, State Board Executive Ex-Officio Gretchen Whitmer, Governor Dr. Michael F. Rice, State Superintendent Table of Contents Introduction 01 Assistive Technology Guidelines Protocol 02 Acknowledgements 02 I. Technology Operations and Concepts 03 II. Creativity and Innovation 08 III. Communication and Collaboration 10 IV. Critical Thinking, Problem Solving, and Decision Making 12 V. Research and Information Literacy 15 VI. Digital Citizenship 18 Assistive Technology Glossary 21 Assistive Technology Resources 32 Assistive Technology Tools & Applications Sample Listing 44 Assistive Technology Tools Record Keeping Chart Instructions 47 Assistive Technology Tools Record Keeping Chart 48 Introduction The Michigan Assistive Technology Guidelines for Teachers of the Blind and Visually Impaired is an expanded document to specifically guide teachers of students who are Blind or Visually Impaired (BVI) in pre-kindergarten through grade 12 with assistive technology (AT). This guide is based on the International Society for Technology in Education (ISTE) Standards to which the Michigan Integrated Technology Competencies -

Brightspace Platform 10.7.3 Release Notes

Brightspace Platform 10.7.3 Release Notes Brightspace Platform 10.7.3 Known Issues Known Issues D2L is committed to releasing high quality products that perform as expected. To keep you informed about the product issues most likely to impact your environment, the Known Issues List consists of newly discovered and commonly reported issues that can be consistently reproduced by D2L. For more information on when an issue was first reported, see the Found in statement in the issue description. Accessibility PRB0055017 If you are using a screen reader and you edit dates of units or try to use the Schedule your units feature in Lessons, the screen reader does not read the dates in the date picker. Additionally, the feedback from the date picker on the date you selected isn't clear. As a workaround, if you are using a screen reader, you can enter the date manually. Found in Brightspace Learning Environment 10.7.2. PRB0055012 In the Firefox browser, if you are using keyboard navigation and a screen reader to navigate the Lessons tool, the focus might not transfer to dialog boxes when they open, but remain on the main page. As a workaround, if you are using keyboard navigation and a screen reader, use the Chrome or Safari browser. Found in Brightspace Learning Environment 10.7.1. PRB0055014 In the Firefox browser, if you are using a keyboard and a NonVisual Desktop Access (NVDA) screen reader to navigate the Lessons tool contents tree, you might be forced out of the tree unexpectedly. As a workaround, use the screen reader to refresh the page and then access the contents tree again. -

Free Assistive Technology Software

Free Assistive Technology Software Blind/Low Vision Fire Vox Fire Vox http://firevox.clcworld.net/ Fire Vox is an open source, freely available talking browser extension for the Firefox web browser. It is a screen reader that is designed especially for Firefox. It is able to identify headings, links, images, etc. and provide navigational assistance. It also provides support for MathML and CSS speech module properties. It works on Windows, Macintosh, and Linux systems. KwikLoupe KwikLoupe Developer http://www.fxc.btinternet.co.uk/assistive.htm This application is a simple screen magnifier. Magnification ranges from 2x to 64x with a quick locate option to position the viewing window. The tool magnifies the area around the mouse pointer. Microsoft Built-In Accessibility Ease of Access Center Windows 7, Vista, and XP include built-in accessibility settings and programs that make it easier to see, hear, and use the computer. Accessibility features in Windows include: speech recognition and text-to- speech; magnifier; on-screen keyboard; keyboard shortcuts; sticky and filter keys; and visual notifications. NVDA (Non Visual Desktop Access) NVDA http://www.oatsoft.org/Software/nvda NonVisual Desktop Access (NVDA) is a free and open-source screen reader for the Windows Operating System, enabling blind and vision impaired people to use their computers. RapidSet Rapid Set Developer http://www.fxc.btinternet.co.uk/assistive.htm RapidSet allows quick and easy changing of the background and font colors, without having to go through the Screen Properties dialogs. Assistive Technology Resource Center Jaclyn Chavarria Colorado State University June 2010 http://atrc.colostate.edu Updated Feb 2013 by Anna Cliff 1 E-Books Bookshare Bookshare http://www.bookshare.org/web/Welcome.html Bookshare.org is an online community that enables people with visual and other print disabilities to legally share scanned books. -

Implementing the ATLAS Self-Driving Vehicle Voice User Interface

Implementing the ATLAS Self-Driving Vehicle Voice User Interface Julian Brinkley Clemson University, School of Computing, Human-Centered Computing Division Shaundra B. Daily Duke University, Department of Computer Science Juan E. Gilbert University of Florida, Computer and Information Science and Engineering [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Abstract This article describes the implementation of the ATLAS self-driving vehicle voice user interface prototype. ATLAS has been designed to support the experiential needs of visually impaired self-driving vehicle users. Keywords Self-Driving Vehicles; Voice User Interface; Accessibility; Visual Impairment; Transportation Journal on Technology and Persons with Disabilities Santiago, J. (Eds): CSUN Assistive Technology Conference © 2019 California State University, Northridge Implementing the ATLAS Self-Driving Vehicle Voice User Interface 134 Introduction The Accessible Technology Leveraged for Autonomous vehicles System, or ATLAS is a prototype human-machine interface intended to support the spatial orientation and navigation needs of self-driving vehicle users with visual disabilities. Within this report we describe the development of the system’s voice user interface and share lessons learned during the development process. We argue that a review of our experiences in implementing the ATLAS VUI may prove beneficial for researchers who may face similar challenges in rapidly prototyping voice user interfaces. Prototype Implementation System Overview The development of ATLAS was motivated by a desire to address the self-driving vehicle accessibility challenges suggested by the visually impaired survey respondents of our prior survey (Brinkley, Daily, et al.), focus groups (Brinkley, Posadas, et al.) and participatory design sessions. This report describes the implementation of the system’s voice user interface specifically. -

Robert Doyle.Pdf

THANK YOU TO Sakarya University for organizing this conference and to the Technische Universitat Wien for hosting us! TOPICS • Convention of the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, United Nations, Articles 20 and 24; • Web accessibility; • United States laws governing accommodations for students with disabilities • Sections 504 and 508 • Americans with Disabilities Act; • Wheelchair Stations; • Assistive Listening Systems; • Demonstrations of students using Assistive Technology; • Favorite Tools of Our Students; • Resources. • Our results. WHAT IS ACCESSIBLE TECHNOLOGY? • Assistive technologies refer to computers or rehabilitative devices, promote greater independence for students with disabilities by changing how these individuals can interact with technology to participate in college courses; • For example, speech recognition software allows users with hand mobility issues to interact with computers using voice commands rather than through manipulating a mouse and keyboard; • Additional assistive technologies include alternative input devices, screen magnifiers, and screen reading software. ADDITIONAL BENEFITS FOR ACCESSIBILITY? • Increasing accessibility can improve the usability of content for all students; • Captions help all students focus on a presentation and understand the professor more clearly; • Accessible documents allow for more flexible student use; • Students, staff, and faculty with temporary injuries benefit from elevators, ramps, and etc.; • Accessible web sites are more usable for all. VIDEO DELETED DUE TO STUDENT -

Technical Information Fabasoft Cloud 2021 September Release

Technical Information Fabasoft Cloud 2021 September Release Valid from September 12, 2021 Copyright © Fabasoft R&D GmbH, Linz, Austria, 2021. All rights reserved. All hardware and software names used are registered trade names and/or registered trademarks of the respective manufacturers. No rights to our software or our professional services, or results of our professional services, or other protected rights can be based on the handing over and presentation of these documents. Fabasoft Cloud 2021 September Release 2 Contents 1 Introduction _____________________________________________________________________________________ 4 2 Supported Platforms ____________________________________________________________________________ 4 2.1 Desktop ........................................................................................................................................................... 4 2.1.1 Office Applications ................................................................................................................................. 4 2.1.2 Multimedia Files ..................................................................................................................................... 5 2.2 Mobile Devices ............................................................................................................................................... 5 2.2.1 Web Browser .......................................................................................................................................... 6 2.2.2 Fabasoft -

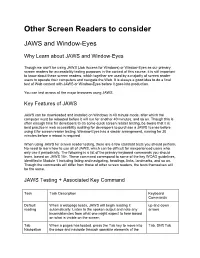

Other Screen Readers to Consider

Other Screen Readers to consider JAWS and Window-Eyes Why Learn about JAWS and Window-Eyes Though we won’t be using JAWS (Job Access for Windows) or Window-Eyes as our primary screen readers for accessibility testing purposes in the context of this course, it is still important to know about these screen readers, which together are used by a majority of screen reader users to operate their computers and navigate the Web. It is always a good idea to do a final test of Web content with JAWS or Window-Eyes before it goes into production. You can test across all the major browsers using JAWS. Key Features of JAWS JAWS can be downloaded and installed on Windows in 40 minute mode, after which the computer must be rebooted before it will run for another 40 minutes, and so on. Though this is often enough time for developers to do some quick screen reader testing, be aware that it is best practice in web accessibility auditing for developers to purchase a JAWS license before using it for screen reader testing. Window-Eyes has a similar arrangement, running for 30 minutes before a reboot is required. When using JAWS for screen reader testing, there are a few standard tests you should perform. No need to learn how to use all of JAWS, which can be difficult for inexperienced users who only use it periodically. The following is a list of the primary keyboard commands you should learn, based on JAWS 15+. These command correspond to some of the key WCAG guidelines, identified in Module 1 including listing and navigating, headings, links, landmarks, and so on.