A Vision of Cincinnati: the Worker Murals of Winold Reiss

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Marquetry on Drawer-Model Marionette Duo-Art

Marquetry on Drawer-Model Marionette Duo-Art This piano began life as a brown Recordo. The sound board was re-engineered, as the original ribs tapered so soon that the bass bridges pushed through. The strings were the wrong weight, and were re-scaled using computer technology. Six more wound-strings were added, and the weights of the steel strings were changed. A 14-inch Duo-Art pump, a fan-expression system, and an expression-valve-size Duo-Art stack with a soft-pedal compensation lift were all built for it. The Marquetry on the side of the piano was inspired by the pictures on the Arto-Roll boxes. The fallboard was inspired by a picture on the Rhythmodic roll box. A new bench was built, modeled after the bench originally available, but veneered to go with the rest of the piano. The AMICA BULLETIN AUTOMATIC MUSICAL INSTRUMENT COLLECTORS’ ASSOCIATION SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2005 VOLUME 42, NUMBER 5 Teresa Carreno (1853-1917) ISSN #1533-9726 THE AMICA BULLETIN AUTOMATIC MUSICAL INSTRUMENT COLLECTORS' ASSOCIATION Published by the Automatic Musical Instrument Collectors’ Association, a non-profit, tax exempt group devoted to the restoration, distribution and enjoyment of musical instruments using perforated paper music rolls and perforated music books. AMICA was founded in San Francisco, California in 1963. PROFESSOR MICHAEL A. KUKRAL, PUBLISHER, 216 MADISON BLVD., TERRE HAUTE, IN 47803-1912 -- Phone 812-238-9656, E-mail: [email protected] Visit the AMICA Web page at: http://www.amica.org Associate Editor: Mr. Larry Givens VOLUME 42, Number -

THE BALDWIN PIANO COMPANY * Singing Boys of Norway Springfield (Mo.) Civic Symphony Orchestra St

Music Trade Review -- © mbsi.org, arcade-museum.com -- digitized with support from namm.org Each artist has his own reason for choosing Baldwin as the piano which most nearly approaches the ever-elusive goal of perfection. As new names appear on the musical horizon, an ever-increasing number of them are joining their distinguished colleagues in their use of the Baldwin. Kurt Adler Cloe Elmo Robert Lawrence Joseph Rosenstock Albuquerque Civic Symphony Orchestra Victor Alessandro Daniel Ericourt Theodore Lettvin Aaron Rosand Atlanta Symphony Orchestra Ernest Ansermet Arthur Fiedler Ray Lev Manuel Rosenthal Baton Rouge Symphony Orchestra Claudio Arrau Kirsten Flagstad Rosina Lhevinne Jesus Maria Sanroma Beaumont Symphony Orchestra Wilhelm Bachaus Lukas Foss Arthur Bennett Lipkin Maxim Schapiro Berkshire Music Center and Festival Vladimir Bakaleinikoff Pierre Fournier Joan Lloyd George Schick Birmingham Civic Symphony Stefan Bardas Zino Francescatti Luboshutz and Nemenoff Hans Schwieger Boston "Pops" Orchestra Joseph Battista Samson Francois Ruby Mercer Rafael Sebastia Boston Symphony Orchestra Sir Thomas Beecham Walter Gieseking Oian Marsh Leonard Seeber Brevard Music Foundation Patricia Benkman Boris Goldovsky Nino Martini Harry Shub Burbank Symphony Orchestra Erna Berger Robert Goldsand Edwin McArthur Leo Sirota Central Florida Symphony Orchestra Mervin Berger Eugene Goossens Josefina Megret Leonard Shure Chicago Symphony Orchestra Ralph Berkowitz William Haaker Darius Milhaud David Smith Pierre Bernac Cincinnati May Festival Theodor Haig -

![J®1]Jill~Filili ®If1f](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5836/j%C2%AE1-jill-filili-%C2%AEif1f-535836.webp)

J®1]Jill~Filili ®If1f

SUMMER1965 VOL. VII, NO. 2 J®1]Jill~filili®IF1f [I[; fil~[;illil©ID~ID~~®©ilfil TI1il®I~J ®IF1f [I[;fil 1fill[; ®ill@ID~ [;~1f [I1]J~ilfil~TI1~ New Baldwin organ tnakes you glad you're old enough to retnember Remember flapper girls, raccoon coats, flag, Play a bass drum or rhythm brushes. pole sitters, the Charleston and silent flicks? Ring the doorbell. Laugh at the auto horn. Sing,alongs to a bouncing ball and the mighty Happy days are here again in this exciting theatre organ? They made the 1920's roar. new Baldwin Theatre Organ. See it at your Now Baldwin has captured the romance Baldwin dealer's today, or mail the coupon of those razzle,dazzle years in a great new below for colorful free brochure. theatre organ for the home. fl:-----------------------------------® Baldwin Piano & Organ Company ~ Remarkably authentic from horseshoe 1801 Gilbert Ave., Dept. T.O.M. 7-65 Cincinnati, Ohio 45202 console to special effects, it has true theatre Please send free brochure on the new Baldwin Theatre organ sound. And the brilliant tone of a Organ. Name _ ______________ _ true Baldwin. Sit down and play yourself some mem, Address _______________ _ ories. Thrill to the shimmering tibias, the City ________ State ____ Zip __ _ romantic kinura, and other theatrical voices In Canada, write: Baldwin Piano Company (Canada) Ltd. ~ 86 Rivalda Road, Weston, Ontario -all sparkling, bright and clear. ~------------------------------------111 BALDWIN AND ORGA-SONIC ORGANS • BALDWIN, ACROSONIC, HAMIL TON AND HOW ARD PIANOS editor of "Theatre Organ". W. "Stu" SUMMER 1965 VOL. -

Howe Collection of Musical Instrument Literature ARS.0167

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8cc1668 No online items Guide to the Howe Collection of Musical Instrument Literature ARS.0167 Jonathan Manton; Gurudarshan Khalsa Archive of Recorded Sound 2018 [email protected] URL: http://library.stanford.edu/ars Guide to the Howe Collection of ARS.0167 1 Musical Instrument Literature ARS.0167 Language of Material: Multiple languages Contributing Institution: Archive of Recorded Sound Title: Howe Collection of Musical Instrument Literature Identifier/Call Number: ARS.0167 Physical Description: 438 box(es)352 linear feet Date (inclusive): 1838-2002 Abstract: The Howe Collection of Musical Instrument Literature documents the development of the music industry, mainly in the United States. The largest known collection of its kind, it contains material about the manufacture of pianos, organs, and mechanical musical instruments. The materials include catalogs, books, magazines, correspondence, photographs, broadsides, advertisements, and price lists. The collection was created, and originally donated to the University of Maryland, by Richard J. Howe. It was transferred to the Stanford Archive of Recorded Sound in 2015 to support the Player Piano Project. Stanford Archive of Recorded Sound, Stanford University Libraries, Stanford, California 94305-3076”. Language of Material: The collection is primarily in English. There are additionally some materials in German, French, Italian, and Dutch. Arrangement The collection is divided into the following six separate series: Series 1: Piano literature. Series 2: Organ literature. Series 3: Mechanical musical instruments literature. Series 4: Jukebox literature. Series 5: Phonographic literature. Series 6: General music literature. Scope and Contents The Howe Musical Instrument Literature Collection consists of over 352 linear feet of publications and documents comprising more than 14,000 items. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 75, 1955-1956, Trip

BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA FOUNDED IN I88I BY HENRY LEE HI 1955 1956 SEASON Veterans Memorial Auditorium, Providence Boston Symphony Orchestra (Seventy-fifth Season, 1955-1956) CHARLES MUNCH, Music Director RICHARD BURGIN, Associate Conductor PERSONNEL Violins Violas Bassoons Richard Burgin Joseph de Pasquale Sherman Walt Concert-master Jean Cauhape Ernst Panenka Alfred Krips Eugen Lehner Theodore Brewster George Zazofsky Albert Bernard Contra-Bassoon Rolland Tapley George Humphrey Richard Plaster Norbert Lauga Jerome Lipson Robert Karol Vladimir Resnikoff Horns Harry Dickson Reuben Green James Stagliano Gottfried AVilfinger Bernard Kadinoff Charles Yancich Einar Hansen Vincent Mauricci Harry Shapiro Joseph Leibovici John Fiasca Harold Meek Emil Kornsand Violoncellos Paul Keaney Roger Shermont Osbourne McConathy Samuel Mayes Minot Beale Alfred Zighera Herman Silberman Trumpets Jacobus Langendoen Roger Voisin Stanley Benson Mischa Nieland Leo Panasevich Marcel Lafosse Karl Zeise Armando Ghitalla Sheldon Rotenberg Josef Zimbler Gerard Goguen Fredy Ostrovsky Bernard Parronchi Clarence Knudson Leon MarjoUet Trombones Pierre Mayer Martin Hoherman William Gibson Manuel Zung Louis Berger William Moyer Kauko Kabila Samuel Diamond Richard Kapuscinski Josef Orosz Victor Manusevitch Robert Ripley James Nagy Flutes Tuba Melvin Bryant Doriot Anthony Dwyer K. Vinal Smith Lloyd Stonestreet James Pappoutsakis Saverio Messina Phillip Kaplan Harps William Waterhouse Bernard Zighera Piccolo William Marshall Olivia Luetcke Leonard Moss George Madsen Jesse -

Bradbury Piano M. Schulz Co. M. Schulz Co. Steger

10 PRESTO June 9, 1923 SPLENDID SHOWING OF ESTABLISHED 1854 PACKARD PIANO COMPANY THE Great Line at Drake Showed Striking Examples of Product of Harmonious Factory. The Packard Piano Co., Fort Wayne, Ind., was BRADBURY PIANO fortunate in its very convenient exhibit location at the Drake Hotel this week. It was close to the ele- FOR ITS vators., and, as Bert Hulme, Packard traveler, said, ARTISTIC EXCELLENCE "right in the line of main dealer travel on the second floor." It was a big room and was always filled with FOR ITS interested groups about the handsome styles shown. Four grands from the Fort Wayne industry showed INESTIMABLE AGENCY VALUE ARTISTIC the ambitious character of the Packard line. Among the force from the Packard Piano Co. pres- THE CHOICE OF II ent at the exhibit was A. S. Bond, president of the Representative Dealers the World Over company, proud of its results of a harmonious indus- IN EVERT try. Others present were A. A. Mahan, sales man- Now Produced in Several ager; Richard S. Hill, eastern sales manager; John J. DETAIL Buttell, midwest representative; H. B. Harris, trav- New Models a eler in Ohio, Indiana and Michigan, and H. M. II Hulme, northwestern wholesale representative. WRITE FOR TERRITORY II •i Factory Executive Offices !• SEEBURG EXHIBIT PROVIDES Leominster, 138th St. and Walton Aye. II HADDORFF PIANO CQ Mass. New York •i WONDER AT DRAKE HOTEL Division W. P. HAINES & CO., Inc. II ROCKFORIMLL. Powerful Tone and Handsome Appearance of Or- •I Wholesale Offices: N»w Tork City Chtatfo S«n Franciaco chestrions Suggest Advantages of Line to Dealers. -

The AMICA BULLETIN

The AMICA BULLETIN AUTOMATIC MUSICAL INSTRUMENT COLLECTORS’ ASSOCIATION NOVEMBER/DECEMBER 2001 VOLUME 38, NUMBER 6 11 Y()UR SIAJON T1CKJ;T 1 M ()JT R I; MAR KA 11 I; c: () N c: I; F-..T J (; F-..I I; J I N "IJT()RY OJ MlISH: / / You have heard great piano performances ... Jacobs Dond, Milton Delcamp-the swift and In a crowded concert hall, some world-famed rhythmic music of Broadway, played by such genius playing to llU::lhed hundreds. Waking the masters ofsyncopationas Lopez,Confrey,Carroll. most glorious of all instruments to glorious life. The Ampico is an integral part of the piano. Releasing, with incredible fingers, the floods of It reproduces through the piano itself-bring melody you have longed to hear-waited pa ing you the actual voice of the instrument in tiently to hear-traveled far, perhaps, to hear. its full beauty-permitting you to study closely Once there was no othcr way to hear great the method and tona of famous pianists-in piano music. Bllt now, in the quictof your own spiring you and your children in your own home, you can hear, any evening, concerts more playing.The Ampico does notinanyway change wonderful still. To your own waiting piano the the appearance, tone or action of the piano. Ampico will bring the playing, not of one artist alone, but of practically all the famous artists You cannot fully believe in this miracle of of the world. You merely touch an electric the Ampico until you hear it! Co, at your first button-then reIa..,;: in your chair to listen. -

Guide to the Chickering & Sons Piano Company Collection

Guide to the Chickering & Sons Piano Company Collection NMAH.AC.0264 Robert Ageton 1989 Archives Center, National Museum of American History P.O. Box 37012 Suite 1100, MRC 601 Washington, D.C. 20013-7012 [email protected] http://americanhistory.si.edu/archives Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 3 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 3 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 2 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 3 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 5 Series 1: Correspondence, 1950............................................................................. 5 Series 2: Publications, 1854-1884........................................................................... 6 Series 3: Company History and Records, 1838-1940.............................................. 9 Series 4: Newspapers, 1847-1876........................................................................ -

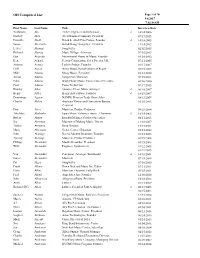

OH Completed List

OH Completed List Page 1 of 70 9/6/2017 7:02:48AM First Name Last Name Title Interview Date Yoshiharu Abe TEAC, Engineer and Innovator d 10/14/2006 Norbert Abel Abel Hammer Company, President 07/17/2015 David L. Abell David L. Abell Fine Pianos, Founder d 10/18/2005 Susan Aberbach Hill & Range Songs Inc., President 11/14/2012 Lester Abrams Songwriter 02/02/2015 Richard Abreau Music Village, Advocate 07/03/2013 Gus Acevedo International House of Music, Founder 01/20/2012 Ken Achard Peavey Corporation, Sales Director UK 07/11/2005 Antonio Acosta Luthier Strings, Founder 01/17/2007 Cliff Acred Amro Music, Band Instrument Repair 07/15/2013 Mike Adams Moog Music, President 01/13/2010 Arthur Adams Songwriter, Musician 09/25/2011 Edna Adams World Wide Music, Former Sales Executive 04/16/2010 Paul Adams Piano Technician 07/17/2015 Hawley Ades Shawnee Press, Music Arranger d 06/10/2007 Henry Adler Henry Adler Music, Founder d 10/19/2007 Dominique Agnew NAMM, Director Trade Show Sales 08/13/2009 Charles Ahlers Anaheim Visitor and Convention Bureau, 01/25/2013 President Don Airey Musician, Product Endorser 09/29/2014 Takehiko Akaboshi Japan Music Volunteer Assoc., Chairman d 10/14/2006 Bulent Akbay Istanbul Mehmet, Product Specialist 04/11/2013 Joy Akerman Museum of Making Music, Docent 11/30/2007 Toshio Akiyama Band Director 12/15/2011 Marty Albertson Guitar Center, Chairman 01/21/2012 John Aldridge Not So Modern Drummer, Founder 01/23/2005 Tommy Aldridge Musician, Product Endorser 01/19/2008 Philipp Alexander Musik Alexander, President 03/15/2008 Will Alexander Engineer, Synthesizers 01/22/2005 01/22/2015 Van Alexander Composer, Arranger, Bandleader d 10/18/2001 James Alexander Musician 07/15/2015 Pat Alger Songwriter 07/10/2015 Frank Alkyer Down Beat and Music Inc, Editor 03/31/2011 Davie Allan Musician, Guitarist, Early Rock 09/25/2011 Fred Allard Amp Sales, Inc, Founder 12/08/2010 John Allegrezza Allegrezza Piano, President 10/10/2012 Andy Allen Luthier 07/11/2017 Richard (RC) Allen Luthier, Friend of Paul A. -

Tony Bacon: 50 Years of Gretsch Electrics Free

FREE TONY BACON: 50 YEARS OF GRETSCH ELECTRICS PDF Tony Bacon | 144 pages | 04 Mar 2005 | BACKBEAT BOOKS | 9780879308223 | English | San Francisco, United States 50 Years of Gretsch Electrics by Tony Bacon, Paperback | Barnes & Noble® Generally speaking, people use it to refer to Gretsch in the s. More specifically, however, it refers to the period when the Baldwin Piano Company owned Gretsch, which was substantially longer—from summer to early The Baldwin era is a much-maligned period in Gretsch history. The term is often used in an unflattering light to denote generally neglectful Baldwin rule that resulted in a decline in quality, unpopular new instruments, corporate upheaval and dwindling sales that ultimately led to Gretsch guitar production being shut down altogether in Gretsch had been a family- run company ever since Friedrich Gretsch founded it in New York in But in the mid s, Tony Bacon: 50 Years of Gretsch Electrics Fred Gretsch Jr. Baldwin, riding high at the time and spurred by its acquisition of U. The sale was completed on July 31, Long successful in building and marketing pianos and organs, Baldwin seemed to assume that its existing production and marketing methods would work equally well for guitars. A few stalwarts hung on, but there was no mistaking a definite decline. For these and other reasons, Baldwin never achieved great success with Gretsch guitars throughout the s. As Tony Bacon: 50 Years of Gretsch Electrics, the unfortunate character of the Baldwin era stands in sharp contrast to the original Gretsch golden age of the s and s. -

130 Years of That Great Gretsch Sound!

130 Years of That Great Gretsch Sound! 1883 Friedrich Gretsch, 27, who emigrated from Germany at 16, opens a small music shop in Brooklyn, N.Y., making banjos, drums and tambourines. 1895 Friedrich Gretsch becomes ill while traveling in Germany and dies at age 39. Fifteen- year-old son, Fred Gretsch, Sr., takes over family business. 1916 Company moves to 10-story building at 60 Broadway in Brooklyn, N.Y. 1918 Fred Gretsch, Sr. develops revolutionary multi-ply drum lamination process resulting in the world’s first “warp free” drum hoop. 1920 Gretsch’s manufacturing facility expands to become the world’s largest music instrument manufacturing factory. 1927 Company introduces historic Gretsch-American drum series, featuring the industry’s first multi-ply drum shell. Gretsch uses its own name on guitars for the first time, rather than just selling to wholesalers. 1935 Broadkaster drum line is introduced. Duke Kramer begins his 70-year career at Gretsch. Known as “Mr. Guitar Man,” Kramer would become pivotal in making Gretsch electric guitars what they are today. 1937 Historic partnership with master drummer and inventor Billy Gladstone begins. The Gretsch-Gladstone drum line is introduced. 1939 Gretsch introduces its first electric guitar - the Electromatic - and the Synchromatic archtop guitar series. Jimmie Webster, guitar innovator and player, joins Gretsch. Distinctive triangle sound hole appears on Gretsch acoustic guitars. 1942 Fred Gretsch, Sr. retires from the company, leaving the day-to-day operations to his sons, Fred Gretsch, Jr. and William “Bill” Gretsch, both of whom had been active in the business since 1927. Gretsch stops instrument production to assist in war efforts. -

Baldwin Piano Company - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia 1/5/14, 5:24 PM Baldwin Piano Company from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Baldwin Piano Company - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia 1/5/14, 5:24 PM Baldwin Piano Company From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia The Baldwin Piano Company was once the largest US- Baldwin Piano Company based manufacturer of pianos and other keyboard instruments. It ceased domestic production of pianos in Type Subsidiary December 2008, and is now a subsidiary of the Gibson Guitar Founded 1857 Corporation. [1] Headquarters Nashville, Tennessee, US Number of locations Greenwood, Mississippi Contents Key people Henry Juszkiewicz (CEO) Parent Gibson Guitars 1 History 2 Notable performers 3 General references 4 References 5 External links History The company traces its origins back to 1857, when Dwight Hamilton Baldwin began teaching piano, organ, and violin in Cincinnati, Ohio. In 1862, Baldwin started a Decker Brothers piano dealership and, in 1866, hired Lucien Wulsin as a clerk. Wulsin became a partner in the dealership, by then known as D.H. Baldwin & Company, in 1873, and, under his leadership, the Baldwin Company became the largest piano dealer in the Midwestern United States by the 1890s. In 1889–1890, Baldwin vowed to build "the best piano that could be built"[2] and subsequently formed two production companies: Hamilton Organ, which built reed organs, and the Baldwin Piano Company, which made pianos. The company's first piano, an upright, began selling in 1891. The company introduced its first grand piano in 1895. Baldwin died in 1899 and left his estate to fund missionary causes. Wulsin ultimately purchased Baldwin's estate and continued the company's shift from retail to manufacturing. The company won its first major award in 1900, when their model 112 won the Grand Prix at the Exposition Universelle in Paris, the first American manufactured piano to win such an award.