Cortriatriatum in Adults Disease Three New Cases and a Brief Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

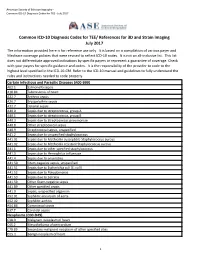

Congenital Cardiac Surgery ICD9 to ICD10 Crosswalks Page 1 of 4 8

Congenital Cardiac Surgery ICD9 to ICD10 Crosswalks ICD-9 code ICD-9 Descriptor ICD-10 Code ICD-10 Descriptor 164.1 Malignant neoplasm of heart C38.0 Malignant neoplasm of heart 164.1 Malignant neoplasm of heart C45.2 Mesothelioma of pericardium 212.7 Benign neoplasm of heart D15.1 Benign neoplasm of heart 425.11 Hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy I42.1 Obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy 425.18 Other hypertrophic cardiomyopathy I42.2 Other hypertrophic cardiomyopathy 425.3 Endocardial fibroelastosis I42.4 Endocardial fibroelastosis 425.4 Other primary cardiomyopathies I42.0 Dilated cardiomyopathy 425.4 Other primary cardiomyopathies I42.5 Other restrictive cardiomyopathy 425.4 Other primary cardiomyopathies I42.8 Other cardiomyopathies 425.4 Other primary cardiomyopathies I42.9 Cardiomyopathy, unspecified 426.9 Conduction disorder, unspecified I45.9 Conduction disorder, unspecified 745.0 Common truncus Q20.0 Common arterial trunk 745.10 Complete transposition of great vessels Q20.3 Discordant ventriculoarterial connection 745.11 Double outlet right ventricle Q20.1 Double outlet right ventricle 745.12 Corrected transposition of great vessels Q20.5 Discordant atrioventricular connection 745.19 Other transposition of great vessels Q20.2 Double outlet left ventricle 745.19 Other transposition of great vessels Q20.3 Discordant ventriculoarterial connection 745.19 Other transposition of great vessels Q20.8 Other congenital malformations of cardiac chambers and connections 745.2 Tetralogy of fallot Q21.3 Tetralogy of Fallot 745.3 Common -

Supplemental Table 1. ICD-9 and ICD-10 Codes

BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance Supplemental material placed on this supplemental material which has been supplied by the author(s) Heart Supplemental Table 1. ICD-9 and ICD-10 Codes ACHD Category Diagnosis ICD-9 Diagnosis or ICD-10 Diagnosis or Procedure Codes Procedure Code Single Common Truncus 745.0 Q20.0 Two Complete Transposition of Great Vessels 745.10, 745.19 Q20.3, Q20.8 Two Double Outlet Right Ventricle 745.11 Q20.1 Two L-Transposition of Great Vessels 745.12 Q20.5 Two Tetralogy of Fallot 745.2 Q21.3 Single Common Ventricle or Double Inlet Ventricle 745.3 Q20.4 Two Ventricular Septal Defect 745.4 Q21.0, I27.83 Two Endocardial Cushion Defect 745.60, 745.69 Q21.2 Two Ostium Primum Atrial Septal Defect 745.61 Q21.2 Two Cor Biloculare 745.70 Q21.1 Two Other Bulbus Cordis Anomaly of Septal Defect 745.80 Q20.8, Q21.4 Two Unspecified Defect of Septal Defect 745.90 Q21.9 Two Pulmonary Valve Anomaly 746.0, 746.09 Q22.3, Q22.2 Two Pulmonary Atresia 746.01 Q22.0 Two Congenital Pulmonary Stenosis 746.02, 746.83 Q22.1, Q24.3 Single Congenital Tricuspid Atresia and Stenosis 746.1 Q22.9, Q22.4, Q22.8 Two Ebstein’s Anomaly 746.2 Q22.5 Two Congenital Mitral Stenosis 746.5 Q23.2 Two Congenital Mitral Insufficiency 746.6 Q23.3 Single Hypoplastic Left Heart Syndrome 746.70 Q23.4 Two Subaortic Stenosis 746.81 Q24.4 Two Cor Triatriatum 746.82 Q24.2 Two Congenital Obstructive Anomalies of Heart 746.84 Q24.8 Two Congenital Coronary Artery Anomaly 746.85 Q24.5 Two Malposition of Heart and Cardiac ApeX 746.87 Q24.0, Q24.1 Two Other Congenital Anomalies of Heart 746.89, 746.90 Q23.8, Q24.8, Q23.9, Q20.9, Q24.9 Two Patent Ductus Arteriosus 747.0 Q25.0 Two Coarctation of Aorta 747.10 Q25.1 Two Interruption of Aortic Arch 747.11 Q25.21 Two Other Congenital Anomalies of Aorta 747.20, 747.21, Q25.4, Q25.41, Q25.42, 747.29 Q25.43, Q25.44, Q25.45, Burstein DS, et al. -

A Presentation of Congenital Cor-Triatriatum

Malaysian Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health (MJPCH) | Vol. 25 (2) December 2019: Page 23 of 27 CASE REPORT OFFICIAL JOURNAL MJPCH Vol. 25 (2) December 2019 UNRESOLVED TACHYPNOEA: A PRESENTATION OF CONGENITAL COR-TRIATRIATUM Fahisham Taib, Nur Atiqah Abdul Rahman, Mohd Rizal Mohd Zain Abstract Cor-triatriatum is a rare cardiac anomaly. In literature, majority case reports on the condition focused on its late presentation in adulthood. It can be easily corrected by surgical intervention to avoid pulmonary congestion and subsequent pulmonary hypertension. We report a rare case of cor-triatriatum with severe pulmonary hypertension in a 7-week-old baby who presented with persistent tachypnoea. Keywords: Received: 1 July 2019; Accepted revised manuscript: 2 Cor-triatriatum; Cardiac failure; Tachypnoea April 2020 Published online: 18 April 2020 Introduction Following completion of antibiotic treatment, Cor-triatriatum is a rare cardiac malformation and baby X maintained his respiratory rate at 65 may present with variation in clinical breaths/minute with saturation of 97% in FiO2 presentation. Its incidence is estimated at about 0.35. There was no adventitious breath sound on 0.1% of all congenital heart disease. In this auscultation, apex beat was palpable at the anomaly, the atrium is divided by a fibromuscular fourth intercostal space midclavicular line with membrane into two distinct chambers: a the presence of loud second heart sound at the posterior- superior chamber which receives the pulmonary area. His liver edge was palpable 1 cm four pulmonary veins and an anterior-inferior below the right costal margin. His chest chamber (true left atrium) which connected to radiograph showed normal cardiac contour with the ventricle via atrioventricular valves. -

Shone Syndrome

Q&A Shone Syndrome A PUBLICATION OF THE ADULT CONGENITAL HEART ASSOCIATION • WWW.ACHAHEART.ORG • 888-921-ACHA (2242) What is Shone syndrome? A supramitral ring is a fibrous membrane that surrounds and Shone syndrome is a collection of eight left-sided obstructive rests on top of the annulus or base of the valve. The membrane heart lesions. These affect blood flow to and from the left looks like an orange peel—thick and fibrous. It can be peeled ventricle, or lower left heart chamber. off of the annulus. This narrows the opening of the valve and results in obstruction. Shone syndrome was identified by Dr. John Shone in 1953. He described four lesions. Now, eight lesions are considered part It has a variable presentation, ranging from mild to severe. of Shone syndrome. A person must have at least three of these Surgical resection is the treatment of choice and it is generally lesions to be diagnosed. Of the eight lesions, supra mitral valve, successful. The recurrence rate is fairly high, especially in parachute mitral valve, subaortic stenosis, and coarctation of young children. For this reason, surgery in children is not the aorta were the first four described. recommended unless it is causing problems. Catheter based techniques (balloon dilation) are sometimes temporarily Because so many different defects are involved, individuals successful. However, the obstruction usually returns. present in varying ways, with a wide range of combinations of defects, symptoms, and issues. The number of lesions does not Individuals present in varying ways, with a wide range necessarily determine the severity of the disease. -

Cor Triatriatum in an Adult

Case Report: Image In Cardiology Nepalese Heart Journal 2017; 14(1): 33-34 Cor Triatriatum in an Adult Anish Hirachan,1 Dipanker Prajapati,2 Madhu Roka,2 Murari Dhungana,2 Deewakar Sharma2 1 National Academy of Medical Sciences, Kathmandu 2 Sahid Gangalal National Heart Centre, Bansbari, Kathmandu Corresponding author: Anish Hirachan Department of Cardiology, National Academy of Medical Sciences, Bir Hospital, Mahaboudha, Kathmandu Email address: [email protected] Abstract A 29 year old female patient presented to the cardiology OPD with history of progressive breathlessness of NYHA class II and palpitation of 1 year duration. Under evaluation, she underwent 2D transthoracic echocardiography that revealed an extra septum that subdivided the left atrium into proximal and distal chambers. The diagnosis of cor triatriatum was hence made and was referred to surgical team for corrective surgery. The communication between proximal and distal chamber was provided by large fenestration in the fibromuscular membrane. Keywords : Cor triatriatum, fenestration ,left atrium Introduction Discussion: Cor triatriatum is a congenital anomaly that was first reported by Cor triatriatum is a rare congenital heart disease (CHD), 0.1% Church in 1868.1 Cor triatriatum sinister (CTS) is a rare congenital of all congenital cardiac defects but a higher incidence, up to anomaly that is caused by a fibromuscular membrane dividing the 0.4% has been reported in autopsies of patients with CHD.3 It’s left atrium (LA) into two chambers. Communication between the a surgically correctable CHD and can occur as an isolated defect pulmonary veins and anterior chamber is provided by fenestrations (classic) or in association with other congenital cardiac anomalies on the membrane. -

Cor Triatriatum in an 86-Year-Old Woman: Initial Presentation with Pulmonary Hypertension Discovered During Preoperative Evaluation Akintunde a A

Case Report Singapore Med J 2011; 52(10) : e203 Cor triatriatum in an 86-year-old woman: initial presentation with pulmonary hypertension discovered during preoperative evaluation Akintunde A A ABSTRACT LA - left atrium Cor triatriatum is a congenital heart malformation RA - right atrium LV - left ventricle that is characterised by the division of the left or RV - right ventricle right atrium into two separate chambers by a membrane or diaphragm. Reports among adults are scarce, as most cases are diagnosed during childhood. The risk of mortality is increased when cor triatriatum is complicated by pulmonary hypertension. This is a report of an 86-year-old woman with World Health Organization Group 2 pulmonary hypertension secondary to cor Fig. 1 4-chamber apical echocardiography image shows the left triatriatum, discovered during preoperative atrium divided by a membranous structure into an upper and workup. Echocardiography showed a membrane lower division associated with floppy interatrial septum. Note dividing the left atrium into two. Doppler studies the membrane and the opening of the membrane dividing the left atrium into two chambers (arrow). revealed a reversal of normal flow, similar to mitral stenosis. The right ventricle was dilated, with reduced long axis function. most of the adults reported were in their fifth or sixth decade of life.(6-8) In this report, an 86-year-old woman Keywords: congenital heart malformation, cor was coincidentally discovered to have cor triatriatum triatriatum, echocardiography, pulmonary during routine preoperative evaluation. hypertension Singapore Med J 2011; 52(10): e203-e205 CASE REPORT An 86-year-old woman was referred to our institution as INTRODUCTION part of her preoperative review for echocardiographic Cor triatriatum was first reported in 1868.(1) It is a rare examination. -

Ashish Kumar D.M ABSTRACT KEYWORDS INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL of SCIENTIFIC RESEARCH

VolumeORIGINAL - 9 | Issue - 8 RESEARCH | August - 2020 PAPER Volume - 9 | Issue - 8 | August - 2020 | PRINT ISSN No. 2277 - 8179 | DOI : 10.36106/ijsr INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF SCIENTIFIC RESEARCH TOTAL SITUS INVERSUS WITH COR TRIATRIATUM SINISTER WITH SUPRAMITRAL RING IN AN ADOLESCENT Cardiology Consultant interventional cardiologist, Oscar superspeciality hospital and trauma center, Ashish Kumar D.M Rohtak, Haryana-124001 ABSTRACT Cor triatriatum sinister is a rare congenital anomaly in which a membrane divides LA into two distinct chambers, supramitral ring is another membrane dividing LA. Combination of both these defects is very rare and these occurring in tandem with complete situs inversus with associated VSD are rarer still. 12 year old female with h/o dyspnea and a systolic murmur presented with complete situs inversus with cor triatriatum sinister with supramitral ring with VSD.Cor triatriatum sinister and supramitral ring and complete situs inversus is a very rare congenial disorder that can be confused clinically with congenital mitral stenosis but can be adequately diagnosed with transthoracic echocardiography and surgical correction is the denitive cure for these anomalies although percutaneous approach can also be tried. KEYWORDS Cor triatriatum sinister; supramitral ring; complete situs inversus; 2D Echocardiography INTRODUCTION: Cor triatriatum is rare congenital cardiac malformation with an estimated incidence of 0.1% of all congenital heart disease and it most commonly occurs on left atrium (Cor triatriatum sinister). Total situs inversus is a rare syndrome, with overall frequency estimated at 1/10,000 births, resulting from abnormal rotation of the cardiac tube during embryogenesis, is characterised by heart on right side of the midline while the liver and the gall bladder are on the left side. -

Common ICD-10 Diagnosis Codes for TEE/ References for 3D and Strain Imaging July 2017 the Information Provided Here Is for Reference Use Only

American Society of Echocardiography - Common ICD-10 Diagnosis Codes for TEE - July 2017 Common ICD-10 Diagnosis Codes for TEE/ References for 3D and Strain Imaging July 2017 The information provided here is for reference use only. It is based on a compilation of various payer and Medicare coverage policies that were revised to reflect ICD-10 codes. It is not an all-inclusive list. This list does not differentiate approved indications by specific payers or represent a guarantee of coverage. Check with your payers for specific guidance and codes. It is the responsibility of the provider to code to the highest level specified in the ICD-10-CM. Refer to the ICD-10 manual and guidelines to fully understand the rules and instructions needed to code properly. Certain Infectious and Parasitic Diseases (A00-B99) A02.1 Salmonella sepsis A18.84 Tuberculosis of heart A22.7 Anthrax sepsis A26.7 Erysipelothrix sepsis A32.7 Listerial sepsis A40.0 Sepsis due to streptococcus, group A A40.1 Sepsis due to streptococcus, group B A40.3 Sepsis due to Streptococcus pneumoniae A40.8 Other streptococcal sepsis A40.9 Streptococcal sepsis, unspecified A41.2 Sepsis due to unspecified staphylococcus A41.01 Sepsis due to Methicillin susceptible Staphylococcus aureus A41.02 Sepsis due to Methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus A41.1 Sepsis due to other specified staphylococcus A41.3 Sepsis due to Hemophilus influenzae A41.4 Sepsis due to anaerobes A41.50 Gram-negative sepsis, unspecified A41.51 Sepsis due to Escherichia coli [E. coli] A41.52 Sepsis due to Pseudomonas -

PDI06 Technical Specifications 150725 Ec2.Xlsx

AHRQ Quality Indicators™ (AHRQ QI™) ICD-9-CM and ICD-10-CM/PCS Specification Enhanced Version 5.0 Pediatric Quality Indicator #06 (PDI #6) RACHS - 1 Pediatric Heart Surgery Mortality Rate October 2015 Provider-Level Indicator Type of Score: Rate Prepared by: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality U.S. Department of Health and Human Services 540 Gaither Road Rockville, MD 20850 www.qualityindicators.ahrq.gov AHRQ QI™ ICD‐9‐CM and ICD‐10‐CM/PCS Specification Enhanced Version 5.0 2 of 14 PDI #06 RACHS‐1 Pediatric Heart Surgery Mortality Rate www.qualityindicators.ahrq.gov PDI #06 RACHS-1 Pediatric Heart Surgery Mortality Rate DESCRIPTION In-hospital deaths per 1,000 pediatric heart surgery admissions among patients with congenital heart disease ages 17 years and younger. Excludes obstetric discharges; cases with transcatheter interventions as a single cardiac procedure, performed without bypass but with catheterization; cases with septal defect repairs as single cardiac procedures without bypass but with catheterization; cases with heart transplants; premature infants with patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) closure as the only cardiac procedure; age less than 30 days with PDA closure as only cardiac procedure; transfers to another hospital; cases with an unknown disposition; and neonates with birth weight less than 500 grams. [NOTE: The software provides the rate per hospital discharge. However, common practice reports the measure as per 1,000 discharges. The user must multiply the rate obtained from the software by 1,000 to report in-hospital deaths per 1,000 hospital discharges.] October 2015 AHRQ QI™ ICD‐9‐CM and ICD‐10‐CM/PCS Specification Enhanced Version 5.0 3 of 14 PDI #06 RACHS‐1 Pediatric Heart Surgery Mortality Rate www.qualityindicators.ahrq.gov PDI #06 RACHS-1 Pediatric Heart Surgery Mortality Rate NUMERATOR Number of deaths (DISP=20) among cases meeting the inclusion and exclusion rules for the denominator. -

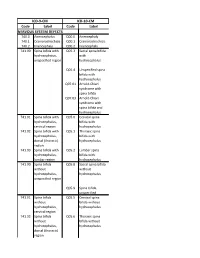

Code Label Code Label NERVOUS SYSTEM DEFECTS ICD-9-CM ICD-10-CM

ICD-9-CM ICD-10-CM Code Label Code Label NERVOUS SYSTEM DEFECTS 740.0 Anencephalus Q00.0 Anencephaly 740.1 Craniorachischisis Q00.1 Craniorachischisis 740.2 Iniencephaly Q00.2 Iniencephaly 741.00 Spina bifida with Q05.3 Sacral spina bifida hydrocephalus, with unspecified region hydrocephalus Q05.4 Unspecified spina bifida with hydrocephalus Q07.01 Arnold-Chiari syndrome with spina bifida Q07.03 Arnold-Chiari syndrome with spina bifida and hydrocephalus 741.01 Spina bifida with Q05.0 Cervical spina hydrocephalus, bifida with cervical region hydrocephalus 741.02 Spina bifida with Q05.1 Thoracic spina hydrocephalus, bifida with dorsal (thoracic) hydrocephalus region 741.03 Spina bifida with Q05.2 Lumbar spina hydrocephalus, bifida with lumbar region hydrocephalus 741.90 Spina bifida Q05.8 Sacral spina bifida without without hydrocephalus, hydrocephalus unspecified region Q05.9 Spina bifida, unspecified 741.91 Spina bifida Q05.5 Cervical spina without bifida without hydrocephalus, hydrocephalus cervical region 741.92 Spina bifida Q05.6 Thoracic spina without bifida without hydrocephalus, hydrocephalus dorsal (thoracic) region 741.93 Spina bifida Q05.7 Lumbar spina without bifida without hydrocephalus, hydrocephalus lumbar region 742.0 Encephalocele Q01.0 Frontal encephalocele Q01.1 Nasofrontal encephalocele Q01.2 Occipital encephalocele Q01.8 Encephalocele of other sites Q01.9 Encephalocele, unspecified 742.1 Microcephalus Q02 Microcephaly 742.2 Reducation Q04.0 Congenital deformities of malformations of brain corpus callosum Q04.1 Arhinencephaly -

Aseexam Review Course

ASEeXAM Review Course Michael D. Pettersen M.D. Director, Echocardiography Rocky Mountain Hospital for Children Denver, CO [email protected] Congenital Heart Disease for the Adult Echocardiographer The vast majority of congenital heart defects are currently detected within the first several years of life. Therefore, the term “adult congenital heart disease” is something of an oxymoron. In the “ancient” days before diagnostic ultrasound, there was less precision in early diagnosis. Improvements in surgical techniques for correcting most congenital cardiac defects have progressed along with our diagnostic skills, making early diagnosis easier and necessary. For all of these reasons, congenital heart disease is more commonly recognized and more frequently diagnosed today than in years past. The result of this is a declining population of adult patients with undiagnosed congenital heart defects. However, the improvements in the success of medical management and surgical repair has led to the growing number of patients who reach adulthood. The clinical course, natural history, and outcome for many of these patients is uncertain because of the time has not allowed for collection of the “unnatural history” of the repaired defects. The ASEexam® will probably deal mainly with issues of unrepaired congenital heart disease. Therefore, these items will be emphasized in this manual and talk. However, questions may appear which deal with knowledge of congenital operations in terms of “what they do”, although the imaging issues are apparently not addressed in detail. Basics Principles of Congenital Heart Disease An understanding of the incidence and frequency of congenital heart disease will aid the clinician in developing an index of suspicion for variation types of defects. -

NJP VOLUME 40 No 1B

Niger J Paed 2012; 40 (1): 88 –90 CASE REPORT Chinawa JM Cor triatriatum sinistrium in a 10 Obu HA year old Nigerian: A case report Eze JC Agwu S Ani OS Okorowo CJ Omeke J DOI:http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/njp.v40i1.18 Accepted: 15th May 2012 Abstract We present a rare and course of their disease. first case of Cor triatriatum sinis- Surgical correction offers good and Chinawa JM ( ) Obu HA trum (CT) in a patient who presents long term results for both classic Department of Paediatrics College of with dyspnoea, easy fatigability, and atypical types. In a resource Medicine University of Nigeria chest pain, murmurs and typical poor country like ours, high index Teaching Hospital. Ituku-Ozalla - Enugu Nigeria. ECG and 2D-echo findings. The of suspicion, early diagnosis and Email: [email protected]. purpose of presenting this case timely referral are warranted so as report is to highlight the distinctive to avert death. Eze JC, Omeke J, Agwu S, Ani OS manifestation of Cor triatriatum Okorowo CJ sinistrum and to provide a concise Key words: Cor triatriatum sinis- Department of Paediatrics Enugu state report of this disease with the hope trium, typical presentation, Nigeria. University of Technology Teaching that such information will help Hospital Park Lane, Enugu, Nigeria. identify patients earlier in the Introduction Examination revealed a malnourished child (mastoid prominence, and loss of muscle bulk ), with an asym- Cor Triatriatum Sinistrum (CT) is a rare but surgically metrical left precordial bulge ; in obvious respiratory correctable congenital cardiac anomaly accounting for distress, (evident by flaring of ala nasi, intercostal and 0.1-0.4% of all congenital cardiac malformation.