The Distribution of Value in the Mobile Phone Supply Chain

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Palm Security WP.Qxd

Palm® Mobility Series: Security Smartphone and handheld security for mobile business. Mobile computing: Opportunities and risk By providing professionals with convenient mobile access to email, business applications, customer information and critical corporate data, businesses can become more productive, streamline business processes and enable better decision making. With the new ease of access to information comes a responsibility to protect the organization's data as well as the investment in mobile devices. In many ways, security risks for mobile computing are similar to those for other computing platforms. There are the usual concerns of protecting data, authenticating users, and shielding against viruses and other malicious Contents code. But because of their mobility and compact size, smartphones and handhelds present some additional challenges: Mobile computing: Opportunities and risk...................................................... 1 Know thy enemy: Security risks...................................................................... 2 • Smartphones and handhelds are more easily lost or stolen than Theft and loss ............................................................................................ 2 laptop or desktop computers. Password cracking .................................................................................... 2 Data interception ...................................................................................... 2 • Users often treat smartphones and handhelds as personal devices Malicious code -

List of Palm OS Versions Included on Palm Handhelds, and Possible Upgrades

List of Palm OS versions included on Palm handhelds, and possible upgrades www.palm.com < Home < Support < Knowledge Library Article ID: 10714 List of Palm OS versions included on Palm handhelds, and possible upgrades Palm OS® is the operating system that drives Palm devices. In some cases, it may be possible to update your device with ROM upgrades or patches. Find your device below to see what's available for you: Centro Treo LifeDrive Tungsten, T|X Zire, Z22 Palm (older) Handspring Visor Questions & Answers about Palm OS upgrades Palm Centro™ smartphone Device Palm OS Handheld Palm OS version Palm Desktop & version (out- Upgrade/Update after HotSync Manager of-box) available? upgrade/update update Centro (AT&T) 5.4.9 No N/A No Centro (Sprint) 5.4.9 No N/A No Treo™ 755p smartphone Device Palm OS Handheld Palm OS version Palm Desktop & version (out- Upgrade/Update after HotSync Manager of-box) available? upgrade/update update Treo 755p (Sprint) 5.4.9 No N/A No Treo™ 700p smartphones Device Palm OS Handheld Palm OS version Palm Desktop & version (out- Upgrade/Update after HotSync Manager of-box) available? upgrade/update update Treo 700p (Sprint) Garnet Yes N/A No 5.4.9 Treo 700p (Verizon) Garnet No N/A No 5.4.9 Treo™ 680 smartphones Device Palm OS Handheld Palm OS version Palm Desktop & version (out- Upgrade/Update after HotSync Manager of-box) available? upgrade/update update Treo 680 (AT&T) Garnet Yes 5.4.9 No 5.4.9 Treo 680 (Rogers) Garnet No N/A No 5.4.9 Treo 680 (Unlocked) Garnet No N/A No 5.4.9 Treo™ 650 smartphones Device Palm OS -

User Guide Mobile Device Setup

USER GUIDE MOBILE DEVICE SETUP Merit Network, Inc. 1000 Oakbrook Drive, Suite 200, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48104-6794 Phone: (734) 527-5700 Fax: (734) 527-5790 E-mail: [email protected] TABLE OF CONTENTS - MERITMAIL, MOBILE DEVICE SETUP MeritMail Mobile Overview 3 Configuring a Windows Mobile 5 device 4 Configuring a Windows Mobile 6 device 5 Resetting your device 5-6 Why is a full resync necessary Performing a full resync Windows Mobile Palm devices (Versamail) Nokia symbian devices Other devices Setup for specific devices 7-13 Motorola Q Phone Nokia E51 Nokia E61 Nokia E62 Nokia E65 Nokia E90 Palm Treo 650 Palm Treo 680 Palm Treo 700w Palm TX Sony Ericsson P910i Sony Ericsson P990i Cingular 8525 Qtek A9100 Limitations 14 2 MeritMail Mobile Overview MeritMail Mobile is the MeritMail synchronization program that provides ‘over-the-air’ mobile data access (email, contacts, calendar) to devices using the native software / UI installed on the device. It works with Symbian S60/S80, Windows® Mobile (WM5), and Palm smartphones. Devices listed below can be configured to work with MeritMail Mobile out of the box. Many more devices work with MeritMail Mobile natively but a sync plug-in is not bundled with the device (plug-in is available via a 3rd party - DataViz). You enable MeritMail Mobile in the ZCS COS or for individual Accounts. Users configure the device’s soft- ware for MeritMail Mobile similarly to how they configure the device to sync against Microsoft® Exchange. The following may need to be configured: . Server address. Type the fully qualified hostname of the user’s MeritMail Collaboration Suite mailbox server. -

44 43% 25% 37% 14

MobileDevices Q Creating Cases Cases as of 7/1/2010 Total from Last Week Cases Created, Year Ago to Date Average Per Day Now Year Ago Change this week 4.3 1.6 173% last 3 months 2.4 1.4 74% last 12 months 2.2 1.9 16% 118 44 Actual Per Day, Last Week vs Qtrly Average 72 76 10 64 70 70 70 6 58 57 58 8 7 44 47 48 49 Last Week 6 4 3 3 Avg This Q 2 0 09 10 10 09 10 09 09 09 09 09 10 10 09 10 - - - - - - - - - - - - Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri Jul Oct Apr Jun- Jan Jun- Mar Feb Nov Dec Aug Sep May May * latest month is month-to-date The Queue Calendar Age of Open Cases Currently Pending Last 12 Months Last 3 months Last Week 100 100 100 14 50 50 50 11 10 4 2 1 1 1 1 1 2 2 more 10 7 4 1 13 11 9 7 5 3 1 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 months ago weeks ago days ago Time Since Last Activity of Any Kind, in Cases that are currently Open Last 12 Months Last 3 months Last Week 100 100 100 50 50 50 14 14 9 1 4 more 10 7 4 1 13 11 9 7 5 3 1 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 months ago weeks ago days ago Closing Cases Estimated Pending Queue over the last six months more than 7 days 80 70 43% 60 3 to 7 days 50 40 25% 30 < 3 days 20 10 37% 0 (over the last six weeks) 1/7 1/21 2/4 2/18 3/4 3/18 4/1 4/15 4/29 5/13 5/27 6/10 6/24 Net change in Q over six months: -4 Prepared by Rob Smyser 7/1/2010 Page 1 MobileDevices Q Cases as of 7/1/2010 Time Worked SyncML This Month SyncML Cases Created TimeWorked on SyncML cases 4.5 4 SyncML cases are software distributions to end-users. -

For Smartphones?

15.912 TECHNOLOGY STRATEGY SPRING SEMESTER 2005 FINAL PAPER SHOULD MOTOROLA EMBRACE 100% THE LINUX OPERATING SYSTEM (OS) FOR SMARTPHONES? Silvia Battigelli Alberto Farronato Carlos Mazariegos 15.912 - Technology Strategy Final Paper 1. Introduction In a period when the market for mobile devices is changing and moving towards convergence of multiple products into one single device, it is time for the big players in all related industries to reconsider their strategy to capture more of the value that convergence will create. Motorola, the second largest manufacturer of mobile handsets, recently adopted a new open source OS in a completely new market, such as the one of smartphones in China, and the question is: should they strongly adopt the new standard in all of the new products and in all of the markets? We believe that the answer is yes, and in this paper we will explain why. 2. An Overview of Motorola Motorola was originally founded as the Galvin Manufacturing Corporation in 1928 by Paul V. Galvin and his brother Joseph E. Galvin in Chicago, Illinois. Galvin Manufacturing Corporation's first product was a battery eliminator, a device that allows battery-powered radios to run on standard household electric current. In the 1930’s the company introduced one of the first commercially successful car radios and a single-frequency mobile radio receiver for police broadcasts. The company had just entered into the new field of mobile radio communications with net annual sales of $287,256. In the 1940’s, after Galvin Manufacturing Corporation becomes Motorola and offers first public stock, and into the 1950’s Motorola kept growing with new technological and commercial innovations in radio devices, television and personal pagers. -

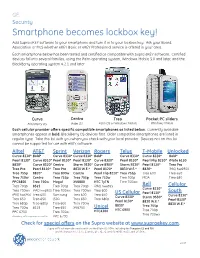

Security Use a Smartphone As Your Lockbox Key! Centro Now Certified!

GE Security Use a smartphone as your lockbox key! Centro now certified! Many agents now use a smartphone or PDA to beam open Supra iBoxes. You can, too, when you subscribe to eKEY service from GE Security! Check with your Board, Association, or MLS for availability of eKEY service in your area. What are smartphones? What are PDA’s? PDA is short for Personal Digital Assistant, commonly called “PalmPilot.” A PDA consolidates your calendar, contacts and other paper systems into one small device you’ll always have with you in your pocket or purse. A smartphone is a PDA that is also a cell phone. Most smartphones include high-speed Internet access, email and other real estate-friendly features, including camera, calculators voice memo capability and more. What is eKEY service? There are two levels of eKEY service. eKEY Basic allows you to open and program your own iBoxes. eKEY Professional adds MLS listing information, maps, agent roster and showing details to your device. With eKEY Professional, you can do business any time, anywhere. See feature comparison chart below. How does an eKEY update? If you are using a smartphone with wireless Internet access, your eKEY will update by itself overnight. If you do not have wireless Internet access, you may update your smartphone through your PC. If you have eKEY service on your PDA, you may update with your PC over your high-speed Internet connection using the factory-supplied PDA cable or cradle. Current smartphone devices Here are the current smartphone devices certified for eKEY service and the wireless carriers supporting them. -

USB Modem User's Guide Version 1.59 for Palmos Contents 1.Introduction

Mobile Stream USB Modem User's Guide Version 1.59 for PalmOS Contents 1.Introduction.............................................................................................................................................2 1.1.About USB Modem.........................................................................................................................2 1.1.1.USB Modem Features..............................................................................................................2 2.Using USB Modem with Windows XP/2000/Vista................................................................................3 2.1.Installation.......................................................................................................................................3 2.1.1.Installing the USB Driver........................................................................................................ 3 2.2.Connecting via USB........................................................................................................................3 2.2.1.Creating a New Connection.....................................................................................................4 2.3.Connecting via Bluetooth................................................................................................................5 2.4.Upgrading........................................................................................................................................5 2.4.1.Upgrading the USB Modem Driver.........................................................................................5 -

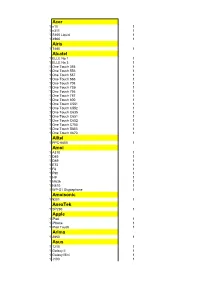

Acer Airis Alcatel Alltel Amoi Amoisonic Anextek Apple Arima

Acer 1 n10 1 1 n311 1 1 S100 Liquid 1 1 X960 1 Airis 1 T480 1 Alcatel 1 ELLE No 1 1 1 ELLE No 3 1 1 One Touch 355 1 1 One Touch 556 1 1 One Touch 557 1 1 One Touch 565 1 1 One Touch 708 1 1 One Touch 735i 1 1 One Touch 756 1 1 One Touch 757 1 1 One Touch 800 1 1 One Touch C551 1 1 One Touch C552 1 1 One Touch C635 1 1 One Touch C651 1 1 One Touch C652 1 1 One Touch C750 1 1 One Touch S853 1 1 One Touch V670 1 Alltel 1 PPC-6800 1 Amoi 1 A310 1 1 D85 1 1 D89 1 1 E72 1 1 F8 1 1 F90 1 1 H9 1 1 M636 1 1 N810 1 1 WP-S1 Skypephone 1 Amoisonic 1 9201 1 AnexTek 1 SP230 1 Apple 1 iPad 1 1 iPhone 1 1 iPod Touch 1 Arima 1 2850 1 Asus 1 1210 1 1 Galaxy II 1 1 Galaxy Mini 1 1 J100 1 1 J101 1 1 J102 1 1 M303 1 1 M530w 1 1 M930 1 1 P320 1 1 P505 1 1 P525 1 1 P526 1 1 P527 1 1 P550 1 1 P552 1 1 P735 1 1 P750 1 1 V80 1 AT&T 1 8900 Tilt 1 1 8925 Tilt 1 Audiovox 1 CDM-8450 1 1 CDM-8450SP 1 1 CDM-8455 1 1 CDM-8615 1 1 CDM-8900 1 1 CDM-8910 1 1 CDM-8912 1 1 CDM-8915 1 1 CDM-8920 1 1 CDM-8930 1 1 PM-8912 1 1 PM-8920 1 1 PPC-6600 / PPC-6601 1 1 PPC-6700 1 1 SMT-5600 1 1 VI600 1 BenQ 1 A500 1 1 A5001 1 1 A520 1 1 CL71 1 1 E72 1 1 E81 1 1 M315 1 1 M350 1 1 M580A 1 1 Morpheus 1 1 P30 1 1 P50 1 1 S660C 1 1 S668C 1 1 S670C 1 1 S680C 1 1 S700 1 1 S7001 1 1 S82 1 1 S830C 1 1 U700 1 1 Z2 1 BenQ-Siemens 1 C81 1 1 C81F 1 1 E71 1 1 EF51 1 1 EF81 1 1 EF91 1 1 EL71 1 1 M81 1 1 P51 1 1 S68 1 1 S80 1 1 S81 1 Bird 1 D660 1 1 E810 1 1 S689 1 1 SC01 1 1 SC24 1 1 V007 1 BlackBerry 1 7100g 1 1 7100i 1 1 7100r 1 1 7100t 1 1 7100v 1 1 7100x 1 1 7105t 1 1 7130c 1 1 7130e 1 1 7130g -

When Choosing a Method of Mobile Data Access, First

Murder M for dial “ ” Murder Maybe M for M for “ ” dial dial “ ” [ Product Analysis ] ayb M e WHEN CHOOSING A METHOD OF MOBILE DATA M ACCESS, FIRST KNOW YOUR USERS. THEN CHECK OUT OUR ROUNDUP OF SMARTPHONES AND for WWAN PC CARDS TO HELP ENSURE A GOOD FIT BY PETER RYSAVY AND DAVE MOLTA We had to cram a lot into this article—the devices and platforms we’re evaluating could fill an entire issue. IT pros wading through piles of “marketecture” from carriers looking to pro- vide wireless data access—for a price—can likely relate. In “Dial M for Maybe” (page 31), we discuss whether mobile users can really enjoy ubiquitous access to enterprise applications and data. Our take: More so than last year, but still less than we’d like. To find out what today’s wireless data net- works can—and cannot—do, we evaluated perform- ance of a trio of PC Card modems from Cingular Wireless, Sprint/Nextel and Verizon Wireless on EDGE (Enhanced Data Rates for Global Evolution), CDMA2000 1XRTT and EV-DO (Evolution-Data Only) networks. We also evaluated the latest crop of smart- phones—from Nokia (Nokia 9300 designed for GPRS/EDGE networks), Sprint (Treo 650 running “ 1XRTT), T-Mobile (RIM BlackBerry 7290 running ” www.nwc.com I 10.27.2005 I NETWORK COMPUTING 41 dial GPRS) and Verizon (Samsung i730 running EV-DO, they are becoming indispensable tools. And in some 1XRTT and Wi-Fi)—to determine their strengths and cases, they can be used as wireless modems for lap- weaknesses in wireless data accessibility. -

Treo 650 GSM Data Sheet

The Treo™ 650 smartphone from palmOne makes it easier than ever to stay connected. It simplifies your life by combining a compact mobile phone with email, an organizer, messaging, and web access.1 There’s also Bluetooth® technology so you can connect wirelessly to other Bluetooth devices, a built-in MP3 player,2 a digital camera that captures video, and a vibrant color screen that brings everything to life. And it supports GSM EDGE networks, a worldwide standard for high-speed wireless data communications. EDGE technology offers fast and secure access to email, the web, and enterprise applications.3 Pick up a smarter phone.The Treo 650 smartphone looks and feels just like a phone, but it’s so much more. You can carry thousands of business and personal phone numbers with you, and then dial any of them by name right from your Contacts list. And a full QWERTY keyboard makes dialing, entering information, and using all of your Treo 650’s functions that much easier. Stay connected with wireless email and messaging.1 VersaMail® wireless email lets you send and receive email from your existing account when you’re away from your desk or out of the office. And you can exchange thoughts and ideas on the fly with text and picture messaging. With the Treo 650 smartphone, you’re always in touch with what’s important to you. Organize your entire world. With Calendar, Contacts, Tasks, and Memos, the Treo 650 smartphone lets you organize your business and personal life—all in one place. You can synchronize your calendar and contacts with your computer, so everything’s always up to date. -

Theawkward Smart Phone Grows Up

-- - I I I I DAVID POGUE TheAwkward Finally, there was a problem with Smart Phone the Treo's memory. It's a special kind that doesn't erase all your data when the Treo's battery dies (unlike most previous Palms), which is Grows Up good. Unfortunately, the new memo- D now, another episode of ry format had a side effect: each tid- gadgetry's long-running bit of information took up a huge '. corporate soap opera, "As amount of storage. An SO-kilobytead- dress book could balloon to 334kilo- A. thePalm Turns."- Previously Qn""A.P.T.": In Season -bytes on the Treo 650,Many who up- I. (1996), Palm Computing developed graded from the Treo 600to the 650 the smash-hit Pilot organizer. The found that their programs and data company was swallowed by U.S. Ro- would no longer fit. botics, which in turn was snapped up- It must be the sweeps season, be- by 3Com. Frustrated, Palm's cause in the last few weeks, all three founders resigned and founded the of those plot twists have finally been rival Handspring. 3Com then spun resolved. In May, Verizon finally out Palm as an independent entity made its ownTreo 650available once again, whereupon it soon split ($400with a two-year commitment). into two companies, PalmOne (hard- Then, two weeks ago, ~print released ware) and PalmSource (software), a software patch that unlocked the and Palm One acquired the ailing Bluetooth laptop-dialing feature. Handspring. Finally, Palm solved the memory In the latest exciting installment, problem. The new software, installed PalmOne has bought back the name on all current Treos (including Veri- Palm from the struggling Palm. -

Smartphone Becomes Lockbox Key! Add Supra Ekey Software to Your Smartphone and Turn It in to Your Lockbox Key

GE Security Smartphone becomes lockbox key! Add Supra eKEY software to your smartphone and turn it in to your lockbox key. Ask your Board, Association or MLS whether eKEY Basic or eKEY Professional service is offered in your area. Each smartphone below has been tested and certifi ed as compatible with Supra eKEY software. Certifi ed devices fall into several families, using the Palm operating system, Windows Mobile 5.0 and later, and the BlackBerry operating system 4.2.1 and later. Curve Centro Treo Pocket PC sliders BlackBerry OS Palm OS Palm OS or Windows Mobile Windows Mobile Each cellular provider off ers specifi c compatible smartphones as listed below. Currently available smartphones appear in bold, BlackBerry OS devices fi rst. Older compatible smartphones are listed in regular type. Take this list with you when you check with your local provider. Devices not on this list cannot be supported for use with eKEY software. Alltel AT&T Sprint Verizon Rogers Telus T-Mobile Unlocked Curve 8330* Bold* Curve 8330* Curve 8330* Bold* Curve 8330* Curve 8320* Bold* Pearl 8130* Curve 8310* Pearl 8130* Pearl 8130* Curve 8320* Pearl 8130* Pearl Flip 8220* iMate 6150 8830* Curve 8320* Centro Storm 9530* Curve 8900* Storm 9530* Pearl 8120* Treo Pro Treo Pro Pearl 8110* Treo Pro 8830 W.E.* Pearl 8120* 8830 W.E.* 8820* iPAQ hw6900 Treo 755p 8820* Treo 800w Centro Pearl Flip 8220* Treo 755p Treo 600 Treo 650 Treo 750w Centro Treo 755p Treo 755p Treo 750w Treo 700p MDA Treo 680 PPC6800 Treo 750w Mogul XV6800 HTC TyTN Treo 700wx Treo 700p 8525 Treo 700p Treo 700p iPAQ hw6955 Bell Cellular Curve 8330* Treo 700wx iPAQ hw6900 Treo 700wx Treo 700wx Treo 600 US Cellular Pearl 8130* South iPAQ hw6900 Treo 600 Samsung Treo 600 Treo 650 Curve 8330* Curve 8330* Storm 9530* Treo 650 Treo 650 i500 Treo 650 Treo 680p Pearl 8130* Pearl 8130* 8830 W.E.* Treo 680p Treo 680p Treo 600 Treo 700w 8830 W.E.* 8830* Treo 755p Treo 700w 8125 Treo 650 XV6700 Unicel HTC 6800 Treo 700p PPC 6700 Treo 700w HTC4300 Treo 700wx *BlackBerry eKEYs require the use of a Fob.