Noack on , 'Rosenstrasse'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Post-1990 Screen Memories: How East and West German Cinema Remembers the Third Reich and the Holocaust

German Life and Letters 59:2 April 2006 0016–8777 (print); 1468–0483 (online) POST-1990 SCREEN MEMORIES: HOW EAST AND WEST GERMAN CINEMA REMEMBERS THE THIRD REICH AND THE HOLOCAUST DANIELA BERGHAHN ABSTRACT The following article examines the contribution of German feature films about the Third Reich and the Holocaust to memory discourse in the wake of German unifi- cation. A comparison between East and West German films made since the 1990s reveals some startling asymmetries and polarities. While East German film-makers, if they continued to work in Germany’s reunified film industry at all, made very few films about the Third Reich, West German directors took advantage of the recent memory boom. Whereas films made by East German directors, such as Erster Verlust and Der Fall Ö, suggest, in liberating contradiction to the anti-fascist interpretation of history, that East Germany shared the burden of guilt, West German productions subscribe to the normalisation discourse that has gained ideological hegemony in the East-West-German memory contest since unification. Films such as Aimée & Jaguar and Rosenstraße construct a memory of the past that is no longer encumbered by guilt, principally because the relationship between Germans and Jews is re-imag- ined as one of solidarity. As post-memory films, they take liberties with the trau- matic memory of the past and, by following the generic conventions of melodrama, family saga and European heritage cinema, even lend it popular appeal. I. FROM DIVIDED MEMORY TO COMMON MEMORY Many people anticipated that German reunification would result in a new era of forgetfulness and that a line would be drawn once and for all under the darkest chapter of German history – the Third Reich and the Holocaust. -

Before the Forties

Before The Forties director title genre year major cast USA Browning, Tod Freaks HORROR 1932 Wallace Ford Capra, Frank Lady for a day DRAMA 1933 May Robson, Warren William Capra, Frank Mr. Smith Goes to Washington DRAMA 1939 James Stewart Chaplin, Charlie Modern Times (the tramp) COMEDY 1936 Charlie Chaplin Chaplin, Charlie City Lights (the tramp) DRAMA 1931 Charlie Chaplin Chaplin, Charlie Gold Rush( the tramp ) COMEDY 1925 Charlie Chaplin Dwann, Alan Heidi FAMILY 1937 Shirley Temple Fleming, Victor The Wizard of Oz MUSICAL 1939 Judy Garland Fleming, Victor Gone With the Wind EPIC 1939 Clark Gable, Vivien Leigh Ford, John Stagecoach WESTERN 1939 John Wayne Griffith, D.W. Intolerance DRAMA 1916 Mae Marsh Griffith, D.W. Birth of a Nation DRAMA 1915 Lillian Gish Hathaway, Henry Peter Ibbetson DRAMA 1935 Gary Cooper Hawks, Howard Bringing Up Baby COMEDY 1938 Katharine Hepburn, Cary Grant Lloyd, Frank Mutiny on the Bounty ADVENTURE 1935 Charles Laughton, Clark Gable Lubitsch, Ernst Ninotchka COMEDY 1935 Greta Garbo, Melvin Douglas Mamoulian, Rouben Queen Christina HISTORICAL DRAMA 1933 Greta Garbo, John Gilbert McCarey, Leo Duck Soup COMEDY 1939 Marx Brothers Newmeyer, Fred Safety Last COMEDY 1923 Buster Keaton Shoedsack, Ernest The Most Dangerous Game ADVENTURE 1933 Leslie Banks, Fay Wray Shoedsack, Ernest King Kong ADVENTURE 1933 Fay Wray Stahl, John M. Imitation of Life DRAMA 1933 Claudette Colbert, Warren Williams Van Dyke, W.S. Tarzan, the Ape Man ADVENTURE 1923 Johnny Weissmuller, Maureen O'Sullivan Wood, Sam A Night at the Opera COMEDY -

International Casting Directors Network Index

International Casting Directors Network Index 01 Welcome 02 About the ICDN 04 Index of Profiles 06 Profiles of Casting Directors 76 About European Film Promotion 78 Imprint 79 ICDN Membership Application form Gut instinct and hours of research “A great film can feel a lot like a fantastic dinner party. Actors mingle and clash in the best possible lighting, and conversation is fraught with wit and emotion. The director usually gets the bulk of the credit. But before he or she can play the consummate host, someone must carefully select the right guests, send out the invites, and keep track of the RSVPs”. ‘OSCARS: The Role Of Casting Director’ by Monica Corcoran Harel, The Deadline Team, December 6, 2012 Playing one of the key roles in creating that successful “dinner” is the Casting Director, but someone who is often over-looked in the recognition department. Everyone sees the actor at work, but very few people see the hours of research, the intrinsic skills, the gut instinct that the Casting Director puts into finding just the right person for just the right role. It’s a mix of routine and inspiration which brings the characters we come to love, and sometimes to hate, to the big screen. The Casting Director’s delicate work as liaison between director, actors, their agent/manager and the studio/network figures prominently in decisions which can make or break a project. It’s a job that can't garner an Oscar, but its mighty importance is always felt behind the scenes. In July 2013, the Academy of Motion Pictures of Arts and Sciences (AMPAS) created a new branch for Casting Directors, and we are thrilled that a number of members of the International Casting Directors Network are amongst the first Casting Directors invited into the Academy. -

Introducing Margarethe Von Trotta

Introducing Margarethe von Trotta The Personal is Political Biography Born 1942 in Berlin; moved to Dusseldorf at war’s end Raised by mother, Elisabeth von Trotta, with only occasional visits from father, painter Alfred Roloff, who died when she was ten Childhood included stint at Protestant boarding school, where von Trotta rebelled against repressiveness of rules, and experiences of being cared for by authoritarian elderly people at boarding houses where mother rented room Education Attended commercial school and worked in office before deciding to study art history Semester at Sorbonneinterest in filmmaking, discovery of French New Wave and other European art cinema (Bergman, Antonioni) Political awareness also began to develop in Paris Return to Germanyfew job prospects for women filmmakers or art historians; turned to German studies, Romance languages and literature and drama Career as Actor Began getting stage roles in 1963 Actor with goal of becoming film director Cast in first movie role in 1968(SchrägeVögel) Career as actor and director concomitant with rise of social and political protest movements, women’s movement and New German Still from Gods of the Plague (Fassbinder, 1970). Cinema Image source: Home Cinema @ The Digital Fix Worked in films by Fassbinder, Hauff, Achternbusch and Schlöndorff Career as Director Began working as writer and assistant director for Volker Schlöndorff in 1970 (married him in 1971) Co-directed The Lost Honor of Katharina Blum (1975) First solo feature: The Second Awakening of Christa -

Kino Kultur Haus

HAUS KINO KULTUR OKTOBER 2018 ÖSTERREICH ZWISCHEN 1948 GESTERN UND MORGEN SURVIVING IMAGES Theater, Film, Musik, Oper, Tanz. Leidenschaftliche Kulturberichterstattung, die alle Stücke spielt, täglich im STANDARD und auf derStandard.at. Kultur_allgemein_110x155.indd 1 28.11.17 10:40 METRO KINOKULTURHAUS PROGRAMM VON 4. OKTOBER BIS 8. NOVEMBER er Oktober – beginnt heuer mit 1948, einem Jahr, das eine Dekade nach dem D»Anschluss« für die heimische Filmindustrie eine Zäsur markierte, in dem die Kinoleinwand Projektionsfläche bot für erste (selbst)kritische Reflexionen. Was mit der Shoah beinahe völlig ausgelöscht wurde, sollte in stummen Filmbildern überleben: im Rahmen der diesjährigen Viennale geht das Filmarchiv Austria mit Surviving Images den Spuren jüdischer Lebenswelten nach und präsentiert damit einen neuen Restaurierungs- und Sammlungsschwerpunkt. Exemplarisch dafür steht die restau- rierte Fassung von DIE STADT OHNE JUDEN, für deren musikalische Neuvertonung keine Geringere als Olga Neuwirth zeichnet, die mit der Uraufführung im Wiener Konzerthaus für ein weiteres Highlight sorgt. Was es bedeutet, wenn junge Israelis ausgerechnet in der Heimat des Holocaust ihre Zukunft sehen, zeigt BACK TO THE FATHERLAND, unser Kinostart. Ein Neuanfang, der – wie so oft – mit einer Reise in die Vergangenheit startet. Ernst Kieninger und das Filmarchiv-Team AUSSTELLUNG DIE STADT OHNE | bis 30.12. 02 DIE STADT OHNE JUDEN ON TOUR | 11.10.–7.11. 05 RETROSPEKTIVEN 1948 – ÖSTERREICH ZWISCHEN GESTERN UND MORGEN 10 4.10.-23.10. V’18: SURVIVING IMAGES | 26.10.–8.11. 28 KINOSTART BACK TO THE FATHERLAND | 12.10.–23.10. 42 FILM | UNIVERSITÄT SELBSTERMÄCHTIGUNG IM ISRAELISCHEN FILM 44 9.10.–16.10. PROGRAMMSCHIENEN SECOND LIFE | 4.10.–23.10. -

NOW^. ^Oor^Open^

an ex-patriate American woman Roland Culver, whose portrait of a flnd'"To Each His Own” too much Olivia Proves who looks very much like, Olivia De taciturn Lord Desham wooing the in the mood of those tearful enter- Havilland may look 25 years from middle-aged American woman is tainments contrived for the radio* now. These passing years are made j lighter for the audiences by some wonderfully comic. daylight hours. But Miss De Havil- Set to Tunes An Actress in There will be those, of course, who i land makes it worthwhile. Stock History Pretty bright glimpses of the varying ^^\Completo g American scene and some able Blank £\ by AMUSEMENTS AMUSEMENTS Earle Film work on the part of the players in- In Lavish Film volved. The most notable of these is Capitol ‘TO EACH HI8 OWN.'1 * Paramount Olivia De with Havilland, produced AMUSEMENTS All Official Pictures from BIKINI VE. Morrison Paper Co. £ / By Jay Carmody eicturey Charles Brackett, directed by Mitchell [At LOEW^i America's history is never more popularly sugar-coated than when Lelsen, screenplay by Charles Brackett and ^^1009 Penn. Ave. N.W. from an Theatres l it is covered with the sweet music of Jerome Kem or Jacques Thery original story by ATOM BOMB vs WARSHIP I Richard Rodgers, Mr. Brackett. At the Earle. with Oscar Hammerstein II as Under these lyricist. conditions, history THE CAST. becomes the most of all and screen themes. SPOT CASH! popular stage What it lacks Miss Norris _Olivia De Havilland of accuracy is more than balanced by what it has of melody and a hack- Corinne Piersen_Mary Anderson Desham_Roland Culver which itself off as Lord neyed quality passes gracefully old-fashioned charm. -

The Director's Idea

The Director’s Idea This Page is Intentionally Left Blank The Director’s Idea The Path to Great Directing Ken Dancyger New York University Tisch School of the Arts New York, New York AMSTERDAM • BOSTON • HEIDELBERG • LONDON NEW YORK • OXFORD • PARIS • SAN DIEGO SAN FRANCISCO • SINGAPORE • SYDNEY • TOKYO Focal Press is an imprint of Elsevier Acquisitions Editor: Elinor Actipis Project Manager: Paul Gottehrer Associate Editor: Becky Golden-Harrell Marketing Manager: Christine Degon Veroulis Cover Design: Alisa Andreola Focal Press is an imprint of Elsevier 30 Corporate Drive, Suite 400, Burlington, MA 01803, USA Linacre House, Jordan Hill, Oxford OX2 8DP, UK Copyright © 2006, Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. Permissions may be sought directly from Elsevier’s Science & Technology Rights Department in Oxford, UK: phone: (ϩ44) 1865 843830, fax: (ϩ44) 1865 853333, E-mail: [email protected]. You may also complete your request on-line via the Elsevier homepage (http://elsevier.com), by selecting “Support & Contact” then “Copyright and Permission” and then “Obtaining Permissions.” Recognizing the importance of preserving what has been written, Elsevier prints its books on acid-free paper whenever possible. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Application submitted British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication -

INEMA INTERNATIONAL Students, Faculty, Staff and the Community Are Invited • ADMISSION IS FREE • Donations Welcome 7:30 P.M

MURRAY STATE UNIVERSITY • Spring 2017 INEMA INTERNATIONAL Students, faculty, staff and the community are invited • ADMISSION IS FREE • Donations Welcome 7:30 p.m. Thursday, Friday and Saturday evenings • Curris Center Theater JAN. 26-27-28 • USA, 1992 MARCH 2-3-4 • USA, 2013 • SHAKESPEARE FESTIVAL THUNDERHEART WARM BODIES Dir. Michael Apted With Val Kilmer, Sam Shephard, Graham Greene. Dir. Jonathan Levine, In English and Sioux with English subtitles. Rated R, 119 mins. With Nicholas Hoult, Dave Franco, Teresa Palmer, Analeigh Tipton, John Malkovich Thunderheart is a thriller loosely based on the South Dakota Sioux Indian In English, Rated PG-13, 98 mins. uprising at Wounded Knee in 1973. An FBI man has to come to terms with his mixed blood heritage when sent to investigate a murder involving FBI A romantic horror-comedy film based on Isaac Marion's novel of the same agents and the American Indian Movement. Thunderheart dispenses with name. It is a retelling of the Romeo and Juliet love story set in an apocalyptic clichés of Indian culture while respectfully showing the traditions kept alive era. The film focuses on the development of the relationship between Julie, a on the reservation and exposing conditions on the reservation, all within the still-living woman, and "R", a zombie…A funny new twist on a classic love story, conventions of an entertaining and involving Hollywood murder mystery with WARM BODIES is a poignant tale about the power of human connection. R a message. (Axmaker, Sean. Turner Classic Movies 1992). The story is a timely exploration of civil rights issues and Julie must find a way to bridge the differences of each side to fight for a that serves as a forceful indictment of on-going injustice. -

Images of Ambivalence: Photography in Margarethe Von Trotta's Die

Graduate Journal of Visual and Material Culture Issue 6 | 2013 Images of Ambivalence: Photography in Margarethe von Trotta’s Die bleierne Zeit Daniel Norford Abstract Taking John Tagg’s intervention in “Evidence, Truth and Order: Photographic Records and the Growth of the State” as its principle point of departure, this paper will investigate the hybrid meanings of photographic imagery in New German Women’s Cinema. Of particular interest will be the marked instances of photographic portraiture in Helma Sanders-Brahm’s Under the Pavement Lies the Strand (1974) and Margarethe von Trotta’s Marianne and Juliane (1981). Drawing from the student movements of ’68 and their aftermath, the crisis of terrorism, the specter of state surveillance and the complex struggles of the feminist movement, my argument will also move in the direction of seeing these phenomena in the context of much broader historical developments in institutional practices across the spectrum of social life. More specifically, I will attempt to articulate and explore the complex inter-textuality that informs the appearance of photographic images in these films, arriving at a perspective that reckons with the over- determined role of photography in modern society. In this way, the photographic image enfolds and disseminates an ambivalent and contradictory set of discourses that resist both state practices of social control, and leftist attempts (in the realms of cinema and art photography) to dramatize a counter-photographic practice. In Derridean terms, then, photography—and in particular portrait photography—is always somewhere “in-between” the discourses which attempt to pinpoint and define it. As such, it (and cinema) is always haunted by a trace-structure which leaves it open to both progressive and regressive lines of flight. -

Katja Riemann

Motzstraße 60 | 10777 Berlin | +49 30 28884330 | [email protected] | die-agenten.de katja riemann Nationalität Deutschland Sprachen Englisch, Französisch Dialekte Berlinerisch, Hamburger, Berndeutsch Größe 172 cm Haarfarbe blond Augenfarbe blau Tanz Jazz, Modern Führerschein B, C Instrumente Gitarre, Klavier, Schlagzeug Gesang Pop Sport Fechten Wohnort Berlin Homepage www.katja-riemann.de/ education Hochschule für Musik und Theater, Hannover Otto Falckenberg Schule, München Lola Rogge Schule, Tanzpädagogik, Hamburg awards 2018 Deutscher Filmpreis, Besucherstärkster Film, "Fack ju Göhte 3" (stellvertretend für Cast und Crew) 2016 Schauspielerpreis des BFFS, Nominierung, Beste Nebendarstellerin, "Mängelexemplar" 2016 Courage Preis, für ihr vielfältiges und beständiges soziales Engagement 2015 Portland German Film Festival Award 2015 WorldFest Houston, Nominierung, Beste Schauspielerin Nebenrolle, "Ohne Dich" 2014 Festival Decine Internacional Deourense, spezielle Erwähnung, "Ohne Dich" 2014 Deutscher Filmpreis, Nominierung, Beste Nebendarstellerin, "Fack Ju Göhte" 2013 Audi Actor Award des Deutschen Regieverbands, Beste Schauspielerin, "Das Wochenende". 2011 Bayerischer Fernsehpreis, Nominierung, Beste Hauptdarstellerin, "Die fremde Familie" 2011 Bambi, Nominierung, Beste Schauspielerin National, "Die fremde Familie" 2011 Schauspielerpreis des BFFS, Nominierung, Beste Hauptdarstellerin, " Die fremde Familie" und "Die Relativitätstheorie der Liebe" 2010 Bundesverdienstkreuz 2009 Grimme-Preis, "Das wahre Leben" 2009 Premio Bacco, Preis -

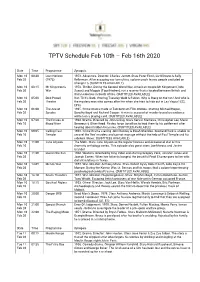

TPTV Schedule Feb 10Th – Feb 16Th 2020

TPTV Schedule Feb 10th – Feb 16th 2020 Date Time Programme Synopsis Mon 10 00:30 Lost Horizon 1973. Adventure. Director: Charles Jarrott. Stars Peter Finch, Liv Ullmann & Sally Feb 20 (1973) Kellerman. After escaping war torn china, a plane crash leaves people secluded on Shangri-La. (SUBTITLES AVAILABLE) Mon 10 03:15 Mr Kingstreet's 1972. Thriller. During the Second World War, American couple Mr Kingstreet (John Feb 20 War Saxon) and Maggie (Tippi Hedren), run a reserve that is located between British and Italian colonies in South Africa. (SUBTITLES AVAILABLE) Mon 10 05:00 Dick Powell Run 'Til It's Dark. Starring Tuesday Weld & Fabian. Why is Stacy on the run? And who is Feb 20 Theatre the mystery man who comes after her when she tries to hide out in Las Vegas? (S2, EP3) Mon 10 06:00 The Ace of 1935. Crime drama made at Twickenham Film Studios. Starring Michael Hogan, Feb 20 Spades Dorothy Boyd and Richard Cooper. A man is accused of murder based on evidence written on a playing card. (SUBTITLES AVAILABLE) Mon 10 07:20 The Pirates of 1962. Drama. Directed by John Gilling. Stars Kerwin Mathews, Christopher Lee, Marie Feb 20 Blood River Devereux & Oliver Reed. Pirates force Jonathon to lead them to his settlement after hearing about hidden treasures. (SUBTITLES AVAILABLE) Mon 10 09:05 Calling Paul 1948. Crime Drama starring John Bentley & Dinah Sheridan. Scotland Yard is unable to Feb 20 Temple unravel the 'Rex' murders and cannot manage without the help of Paul Temple and his sidekick 'Steve'. (SUBTITLES AVAILABLE) Mon 10 11:00 June Allyson The Moth. -

Relações Raciais, Gênero E Memória: a Trajetória De Ruth De Souza Entre O Teatro Experimental Do Negro E O Karamu House (1945-1952)

1 UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL FLUMINENSE INSTITUTO DE CIÊNCIAS HUMANAS E FILOSOFIA ÁREA DE HISTÓRIA PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM HISTÓRIA SOCIAL Júlio Cláudio da Silva Relações raciais, gênero e memória: a trajetória de Ruth de Souza entre o Teatro Experimental do Negro e o Karamu House (1945-1952) Tese apresentada no Programa de Pós-Graduação em História da Universidade Federal Fluminense, sob a orientação da Professora Doutora Hebe Mattos, como requisito parcial para a obtenção do título de Doutor. Niterói Abril de 2011 2 Ficha catalográfica elaborada pela Biblioteca Central do Gragoatá S586 Silva, Júlio Cláudio da. Relações raciais, gênero e memória: a trajetória de Ruth de Souza entre o Teatro Experimental do Negro e o Karamu House (1945- 1952). / Júlio Cláudio da Silva. – 2011. 277 f.; il. Orientador: Hebe Maria Mattos de Castro. Tese (Doutorado) – Universidade Federal Fluminense, Instituto de Ciências Humanas e Filosofia, Departamento de História, 2011. Bibliografia: f. 243-251. 1. Souza, Ruth de, 1921- . 2. Relações raciais. 3. Teatro experimental. I. Castro, Hebe Maria Mattos de. II. Universidade Federal Fluminense. Instituto de Ciências Humanas e Filosofia. III. Título. CDD 927.92028 3 Júlio Cláudio da Silva Relações raciais, gênero e memória: a trajetória de Ruth de Souza entre o Teatro Experimental do Negro e o Karamu House (1945-1952) Tese apresentada no Programa de Pós-Graduação em História da Universidade Federal Fluminense, sob a orientação da Professora Doutora Hebe Mattos, como requisito parcial para a obtenção do título de Doutor. Banca Examinadora: ___________________________________________ Prof.a Dr. a Hebe Mattos(UFF) (Orientadora) ___________________________________________ Prof.a Dr. a Martha Abreu (UFF) ___________________________________________ Prof.a Dr.