Gaelic Football in Cleveland: Early Days

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Treoir Oifigiúil Official Guide

An Treoir Oifigiúil Cuid a dó 2018-2021 Official Guide Part 2 Official Playing Rules www.facebook.com/officialcamogieassociation www.instagram.com/officialcamogie www.camogie.ie www.twitter.com/officialcamogie officialcamogie This is An Treoir Oifigiúil Cuid a Dó (Official Playing Rules 2018-2021) The other binding parts are as follows: • Part I Official Guide • Part III Code of Practice for all Officers of the Association • Part IV Disciplinary Code and THDC Mandatory Procedures • Part V Association Code on Sponsorship • Part VI Code for Camogie Supporters’ Club • Part VII Code of Behaviour (Underage) Effective from May 7th 2018 In the case of competitions at any level of the Association, that commenced prior to May 7th 2018, these competitions will be administered under the playing rules effective at the commencement of the competition. The Camogie Association Croke Park Dublin 3 Tel: 01 865 8651 Email: [email protected] Web: www.camogie.ie OFFICIAL GUIDE – Part 2 – Official Playing Rules 2018-2021 Contents 15 A-SIDE CAMOGIE ...................................................................................... 2 1. Name of the Game .................................................................................. 2 2. Team Lists ................................................................................................ 2 3. Teams’ Composition ................................................................................ 3 4. Duration of Games .................................................................................. 3 5. -

Player Pathway Phases of a Camogie Player’S Development 1

Camogie Player Pathway Phases of a camogie player’s development 1 A message from the Director of Camogie Development The Camogie Player Pathway describes the opportunities to play Camogie from beginner to elite level. It is designed to give every person entering the game the chance to reach their personal potential within the sport. The pathway is divided into six stages: n Phase 1 – Get a grip 6-8 yrs approx n Phase 2 – Clash of the ash 9-11 yrs approx n Phase 3 – Get hooked 12-14 yrs approx n Phase 4 – Solo to success 15-17 yrs approx n Phase 5 – Strike for glory 17+ yrs approx n Retainment – Shifting the goalposts There are opportunities for everyone to play camogie, irrespective of age, ability, race, culture or background. The Camogie Association has adopted a logical approach to player development, so that every child and adult can reach their potential and enjoy Camogie throughout their lifetime. There are six progressive steps in a Camogie Player Pathway. Individuals will spend varying amounts of time mastering the relevant skills and attaining the requisite fitness levels. All participants should reach their potential in the stage that matches their age and aspirations. 2 For the most talented players, the player pathway ensures that they are given the very best opportunities and support to reach their full potential. Dr Istvan Baly’s Long-term Athlete Development model (LTAD) focuses on best practice in the development of players at every level. Camogie uses LTAD to develop the skills, coaches and competitions that are appropriate at each age and stage of player development. -

The Work-Rate of Substitutes in Elite Gaelic Football Match-Play

The Work-Rate of Substitutes in Elite Gaelic Football Match-Play The Work-Rate of Substitutes in Elite Gaelic Football Match-Play Eoghan Boyle 1, Joe Warne 1 2, Alan Nevill 3 Kieran Collins 1 1Gaelic Sports Research Centre, Technological University Dublin - Tallaght Campus, Dublin, Ireland,2Setanta College, Thurles, Tipperary, Ireland, and 3Faculty of Education, Health and Wellbeing, University of Wolverhampton, UK Running performance j High-intensity j Substitutes j Positional variation Headline Methodology ccording to a study assessing changes in match running During competitive match-play over two seasons, running per- Aperformance in elite Gaelic football players, there is a sig- formance was measured via a global positioning system (GPS) nificant reduction in relative high-speed distance (RHSD) in sampling at 10-Hz (VX Sport, New Zealand) in a total of 23 the second, third and fourth quarters when compared to the games. Dependent variables consisted of relative total dis- first quarter [1]. Subbed on players in elite soccer were re- tance (RTD; m·min−1), relative high-speed distance (m·−1; ported to cover greater RHSD (19.8 { 25.1 km·h−1) compared ≥17km·h−1), peak speed (km·h−1), peak metabolic power and to full game players [2]. In elite Rugby union, subbed on play- sprints per minute (accel·min−1). Relative total distance was ers generally demonstrated improved running performance in calculated as the total distance (metres) from a single match comparison to full game and subbed off players. Subbed on divided by match-play duration in minutes. Relative high- players also reported a better running performance over their speed distance was calculated as the total high-speed distance first 10 minutes of play compared to the final 10 minutes of (metres; ≥17km·h−1) from a single match divided by match- play of whom they replaced [3]. -

Sports Directory

SPORTS DIRECTORY LISBURN & CASTLEREAGH DIRECTORY OF SPORT 2018/2019 CONTENTS Foreword 4 Dundonald International Ice Bowl 40 Chairman’s Remarks 5 Castlereagh Hills Golf Course 42 Sport Lisburn & Castlereagh 6 Aberdelghy Golf Course 42 Sports Bursaries 8 Laurelhill Sports Zone 44 Elite Athlete Club 10 Maghaberry Community Centre 45 The 2017 Draynes Farm Sports Awards 11 Bridge Community Centre 46 Sporting Achievements of the Month Awards 14 Irish Linen Centre & Lisburn Museum 46 Lisburn & Castlereagh City Council’s Annual Outdoor Facilities 47 Sports and Leisure Events 15 Parks 50 Lisburn & Castlereagh City Council Clubmark NI 58 - After School Programmes 16 Sports Development Unit 59 Grove Activity Centre 18 Every Body Active 2020 60 Glenmore Activity Centre 20 Irish Football Association - Grassroots Development Centre 61 Kilmakee Activity Centre 22 Easter Sporting Challenge 62 Hillsborough Village Centre 24 Summer Sports Programme 63 ISLAND Arts Centre 26 After Schools Clubs 63 Lagan Valley LeisurePlex 28 Lisburn Coca-Cola HBC Half Marathon, 10K Road Race Moneyreagh Community Centre 32 and Fun Run 64 Enler Community Centre 34 City of Lisburn Triathlon and Aquathlon 65 Ballyoran Community & Resource Centre 36 Santa Dash 65 Lough Moss Leisure Centre 38 Sports Clubs Directory 66 Acknowledgements: Photographs supplied courtesy of Lisburn & Castlereagh City Council, and affiliated sports clubs. 2 3 FOREWORD CHAIRMAN’S REMARKS As Chairman of Lisburn & Castlereagh City Council’s Leisure & If you would like your Club or Sports Organisation to be included in the Sport Lisburn & Castlereagh has been providing support and funding A comprehensive range of services are available, including financial Community Development Committee, I take great pleasure in providing next edition of the Lisburn & Castlereagh Directory of Sport or to receive to Lisburn & Castlereagh Sports Clubs and individuals for over thirty assistance and support for clubs and individuals. -

Tuarascáil an Ard Stiúrthóra

An Chomhdháil Bhliantúil 2014 5 Tuarascáil an Ard Stiúrthóra Camogie Rising in our 110th year, it is encouraging to report a decade of buoyancy. Croke Park, Sunday 15th September 2013. The final whistle is blown. The first part of my report below captures key Therese Maher falls to her knees. Lorraine Ryan elements of this experience of Camogie Rising becomes only the second Galway player ever to from 2003-2013. walk up the Hogan Stand steps to collect the ‘‘ O’Duffy Cup. Iconic images are captured forever. Part B provides an account of the key activities undertaken at national level of the Camogie Therese’s story is remarkable and Association during 2013. compelling for: Part C provides an overview of • Her endurance in maintaining our performance in relation to a top flight inter-county career In an era when our five year National over 16 years; women’s sport is Development Plan Our Game • Overcoming the pain of five All- ‘‘ Our Passion 2010-2015 . Ireland Final defeats to claim a progressing, and in first All-Ireland senior victory; our 110th year, it is Significant club growth • Pride in club, county and encouraging to Ten years on from our Centenary province; report a decade of is a useful benchmark to reflect • A commitment to the highest buoyancy on the direction of the standards of skill, athleticism, Association, and to do so teamwork and leadership. drawing on and analysing the data we collect each year. Therese’s story is also compelling because it tells us about ourselves. It symbolises the passion we Using 2003 data as a baseline, there was a 23 per all share for our game. -

The Development of Grassroots Football in Regional Ireland: the Case of the Donegal League, 1971–1996

33 Conor Curran ‘It has almost been an underground movement’. The Development of Grassroots Football in Regional Ireland: the Case of the Donegal League, 1971–1996 Abstract This article assesses the development of association football at grassroots’ level in County Donegal, a peripheral county lying in the north-west of the Republic of Ire- land. Despite the foundation of the County Donegal Football Association in 1894, soccer organisers there were unable to develop a permanent competitive structure for the game until the late 20th century and the more ambitious teams were generally forced to affiliate with leagues in nearby Derry city. In discussing the reasons for this lack of a regular structure, this paper will also focus on the success of the Donegal League, founded in 1971, in providing a season long calendar of games. It also looks at soccer administrators’ rivalry with those of Gaelic football there, and the impact of the nationalist Gaelic Athletic Association’s ‘ban’ on its members taking part in what the organisation termed ‘foreign games’. In particular, the extent to which the removal of the ‘ban’ in 1971 helped to ease co-operation between organisers of Gaelic and Association football will be explored. Keywords: Association football; Gaelic football; Donegal; Ireland; Donegal League; Gaelic Athletic Association Introduction The nationalist Gaelic Athletic Association (GAA), which is today the leading sporting organisation in Ireland despite its players having to adhere to its amateur ethos, has its origins in the efforts of schoolteacher and journalist Michael Cusack, who was eager to reform Irish athletics which was dominated by elitism and poorly governed in the early 1880s. -

Camogie Development Plan 2019

Camogie Development Plan 2019 - 2022 Vision ‘an engaged, vibrant and successful camogie section in Kilmacud Crokes – 2019 - 2022’ Camogie Development Ecosystem; 5 Development Themes Pursuit of Camogie Excellence Funding, Underpinning everything we do: Part of the Structure & ➢ Participation Community Resources ➢ Inclusiveness ➢ Involvement ➢ Fun ➢ Safety Schools as Active part of the Volunteers Wider Club • A player centric approach based on enjoyment, skill development and sense of belonging provided in a safe and friendly environment • All teams are competitive at their age groups and levels • Senior A team competitive in Senior 1 league and championship • All players reach their full potential as camogie players • Players and mentors enjoy the Kilmacud Crokes Camogie Experience • Develop strong links to the local schools and broader community • Increase player numbers so we have a minimum of 40 girls per squad OBJECTIVES • Prolong girls participation in camogie (playing, mentoring, refereeing) • Minimize drop-off rates • Mentors coaching qualifications are current and sufficient for the level/age group • Mentors are familiar with best practice in coaching • Well represented in Dublin County squads, from the Academy up to the Senior County team • More parents enjoying attending and supporting our camogie teams Milestones in Kilmacud Crokes Camogie The Camogie A dedicated section was nursery started U16 Division 1 Teams went from started in 1973 by County 12 a side to 15 a Promoted Eileen Hogan Champions Bunny Whelan side- camogie in -

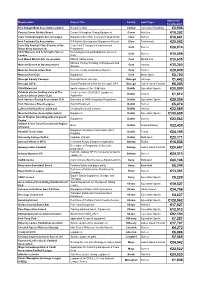

Grid Export Data

Amount to Organisation Project Title County Sport Type be allocated Irish Dragon Boat Association Limited Buoyancy Aids Carlow Canoeing / Kayaking €3,998 County Cavan Athletic Board Cavan / Monaghan Timing Equipment Cavan Athletics €19,302 Clare Schoolboy/girls Soccer League Equipment for CSSL newly purchased facility Clare Soccer €18,841 Irish Taekwon-Do Association ITA Athlete Development Equipment Project Clare Taekwondo €20,042 Cork City Football Club (Friends of the Cork City FC Equipment Improvement Cork Soccer Rebel Army Society Ltd) Programme €28,974 Cork Womens and Schoolgirls Soccer Increasing female participation in soccer in Cork Soccer League Cork €10,599 Irish Mixed Martial Arts Association IMMAF Safety Arena Cork Martial Arts €10,635 Munster Hockey Funding for Equipment and Munster Branch of Hockey Ireland Cork Hockey Storage €35,280 Munster Cricket Union CLG Increase facility standards in Munster Cork Cricket €29,949 Munster Kart Club Equipment Cork Motor Sport €2,700 Donegal County Camogie Donegal Senior camogie Donegal Camogie €1,442 Donegal LGFA Sports Equipment & Kits for Donegal LGFA Donegal Ladies Gaelic Football €8,005 ChildVision Ltd sports equipment for ChildVision Dublin Equestrian Sports €30,009 Cricket Leinster (trading name of The Cricket Leinster 2020/2021 Equipment Dublin Cricket Leinster Cricket Union CLG) Application €1,812 Irish Harness Racing Association CLG Extension of IHRA Integration Programme Dublin Equestrian Sports €29,354 Irish Homeless Street Leagues Sports Equipment Dublin Soccer €5,474 Leinster -

Sports Council for Glasgow Membership List, August 2019

www.scglasgow.org.uk Sports Council For Glasgow Membership List, August 2019 Name Sport Andrew Steen Individual Member Archie Graham O.B.E. Honorary Life Member Argo Boxing Club Boxing Bernie Mitchell Individual Member Carmyle Bowling Club Bowls Castlemilk Gym Weightlifting Ceann Craige Hurling and Comogie Club Hurling / Camogie City of Glasgow SEALS Swimming City of Glasgow Swim Team Swimming Clyde Amateur Rowing Club Rowing Clydesdale Amateur Rowing Club Rowing Clydesdale Cricket Club Cricket Cricket Scotland Cricket David Mackie Individual Member Dilawer Singh M.B.E. Individual Member Drumchapel & Clydebank Kayak Club Kayaking Drumchapel & District Sports Centre Multi-sport Drumchapel Lawn Tennis Club Tennis Drumchapel Table Tennis Development Scheme Table Tennis Drumchapel United Football Elaine Mackay Individual Member Frank Clement Honorary Life Member Fusion Football Club Football Garscube Harriers Club Athletics GBM Fitness Multi-sport GHK Ladies Hockey Club Hockey Glasgow & North Strathclyde Badminton Group Badminton Glasgow Academical Sports Club Multi-sport Glasgow Afghan United Football Glasgow Athletics Association Athletics Glasgow City Cup Football Glasgow City Football Club Football Glasgow Coastal Rowing Club Rowing Glasgow Deaf Golf Club Golf Glasgow Devils Basketball Club Basketball Glasgow Disability Badminton Club Badminton Glasgow Disability Sport Multi-sport Glasgow Disability Tennis Tennis Glasgow Eagles Multi-sport Glasgow East Juniors RFC Rugby Glasgow Fever Basketball Club Basketball Sports Council for Glasgow -

Rugby Sevens Match Demands and Measurement of Performance: a Review

Henderson, M.J. et al.: RUGBY SEVENS MATCH DEMANDS... Kinesiology 50(2018) Suppl.1:49-59 RUGBY SEVENS MATCH DEMANDS AND MEASUREMENT OF PERFORMANCE: A REVIEW Mitchell J. Henderson1,2,3,, Simon K. Harries2, Nick Poulos2, Job Fransen1,3, and Aaron J. Coutts1,3 1University of Technology Sydney (UTS), Sport & Exercise Discipline Group, Faculty of Health, Australia 2Australian Rugby Sevens, Australian Rugby Union (ARU), Sydney, Australia 3University of Technology Sydney (UTS), Human Performance Research Centre, Australia Review UDC: 796.333.3: 796.012.1 Abstract: The purpose of this review is to summarize the research that has examined the match demands of elite-level, men’s rugby sevens, and provide enhanced understanding of the elements contributing to successful physical and technical performance. Forty-one studies were sourced from the electronic database of PubMed, Google Scholar and SPORTDiscus. From these, twelve original investigations were included in this review. Positive match outcomes are the result of an interplay of successful physical, technical, and tactical performances. The physical performance of players (activity profile measurement from GPS) includes high relative total distance and high-speed distance values in comparison to other team sports. The technical performance of players (skill involvement measurement from match statistics) involves the execution of a range of specific offensive and defensive skills to score points or prevent the opponent from scoring. The factors influencing change in these performance constructs has not been investigated in rugby sevens. There is a paucity in the literature surrounding the situational and individual factors affecting physical and skill performance in elite rugby sevens competition. Future studies should investigate the factors likely to have the strongest influence on player performance in rugby sevens. -

Activity Profile, Playerload™ and Heart Rate Response of Gaelic Football Players: a Pilot Study

Original Article Activity profile, PlayerLoad™ and heart rate response of Gaelic football players: A pilot study DECLAN GAMBLE1,2 , MATT SPENCER3,4, ANDREW MCCARREN5, NIALL MOYNA2 1Sport Northern Ireland Sports Institute, Ulster University, Newtownabbey, N. Ireland, United Kingdom 2School of Health and Human Performance, Dublin City University, Dublin, Ireland 3Department of Physical Performance, Norwegian School of Sport Sciences, Oslo, Norway 4Department of Public Health, Sport and Nutrition, University of Agder, Kristiansand, Norway 5Insight Centre for Data Analytics, Dublin City University, Dublin, Ireland ABSTRACT The objectives of this study were to; quantify positional differences in the activity profiles of Gaelic football players and to evaluate decrements in physical performance during a pre-season competition. Global positioning system (GPS) data was recorded from 36 players from 3 teams across 5 games. The relative distance covered in locomotor activities, peak speed, relative PlayerLoad™ (PL.min-1) and heart rate responses were evaluated between playing positions and across match periods using a mixed model analysis. The mean relative distance of 92.4 ± 23.3 m.min-1 covered, comprised 28.4 ± 10.2 m.min-1 of high intensity running (m.min-1 ≥ 4.0 m.s-1) and 9.9 ± 3.9 m.min-1 of very high intensity running (m.min-1 ≥ 5.5 m.s-1). High intensity running and relative PlayerLoad™ (PL.min-1) was significantly higher in half-backs, midfielders and half-forwards compared to the full-backs, whereas only the half-backs and half-forwards displayed significantly greater values compared to full-forwards. When compared to the first 15 min (P1) of the game, analysis of pooled positional data revealed significant declines in; overall relative distance covered, jogging (≥2.0 - < 4.0 m.s-1), running (≥4.0 - <5.5 m.s-1), high intensity running and PL.min-1,in P2 (20-35 min) and P4 (55-70 min). -

INTRODUCTION This Booklet Contains a Brief Version of the Playing Rules of Ladies Gaelic Football

INTRODUCTION This booklet contains a brief version of the playing rules of Ladies Gaelic Football. The full version of the Playing Rules is contained in the Official Guide. Its aim is to try to ensure that all players and officials read and learn the rules. It is important that teachers and coaches ensure that all their players have a copy of this booklet. This will improve their understanding of the game and help them to accept the decisions of the officials without dissent. This booklet emphasises the importance which the Association places on promoting a better understanding of our game. 11 FIELD OF PLAY 1. Ladies Gaelic Football is played on a full size GAA pitch from Under 14 upwards. The pitch may be reduced in size for Under 13 and younger grades. 2. The dimensions of the field of play, scoring space and the duration of the game may be reduced by the organising committee for competitions less than 15 a side. PLAYER 1. A player who may be pregnant, suffering from concussion etc. should not play Ladies Gaelic Football. However should she play, she shall do so entirely at her own risk, and the Ladies Gaelic Football Association cannot be held responsible for any consequences that may arise. PLAYERS ATTIRE 1. The attire for playing Ladies Gaelic Football is jersey, shorts, socks and boots. Players cannot wear jewellery, ear rings, hair slides or other items that may cause injury whilst playing Ladies Gaelic Football. 2. From 1st January 2014 All underage players must wear a mouth guard while playing ladies Gaelic Football unless advised otherwise, in writing, not to do so by a qualified Doctor or Dentist.