A Close and Distant Reading of Shakespearean Intertextuality

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Macbeth Silly Shakespeare Sample

ISBN: 978-1-948492-74-4 Copyright 2020 by Paul Murray All rights reserved. Our authors, editors, and designers work hard to develop original, high-quality content. Please respect their efforts and their rights under copyright law. Do not copy, photocopy, or reproduce this book or any part of this book for use inside or outside the classroom, in commercial or non-commercial settings. It is also forbidden to copy, adapt, or reuse this book or any part of this book for use on websites, blogs, or third-party lesson-sharing websites. For permission requests or discounts on class sets and bulk orders contact us at: Alphabet Publishing 1204 Main Street #172 Branford, CT 06405 USA [email protected] www.alphabetpublishingbooks.com For performance rights, please contact Paul Murray at [email protected] Interior Formatting and Cover Design by Melissa Williams Design Summary acbeth (or The Tragedy of Macbeth to give it its full Mtitle), believed to be first performed in 1606, is one of Shakespeare’s most famous and widely performed plays. Some say that the play is cursed because of the way in which it portrays the witches and so tradition has it that the name of the play should not be spoken in theatre; instead it is referred to simply as ‘the Scottish play’. *** The Scottish play begins with the brief appearance of a trio of witches who act as the narrators for this version of the play, appearing between each scene. It then moves to a military camp, where the Scottish King Duncan hears the news that his generals, Macbeth, and Banquo, have defeated two separate invading armies—one from Ireland and one from Norway. -

Living Under Drones Death, Injury, and Trauma to Civilians from US Drone Practices in Pakistan

Fall 08 September 2012 Living Under Drones Death, Injury, and Trauma to Civilians From US Drone Practices in Pakistan International Human Rights and Conflict Resolution Clinic Stanford Law School Global Justice Clinic http://livingunderdrones.org/ NYU School of Law Cover Photo: Roof of the home of Faheem Qureshi, a then 14-year old victim of a January 23, 2009 drone strike (the first during President Obama’s administration), in Zeraki, North Waziristan, Pakistan. Photo supplied by Faheem Qureshi to our research team. Suggested Citation: INTERNATIONAL HUMAN RIGHTS AND CONFLICT RESOLUTION CLINIC (STANFORD LAW SCHOOL) AND GLOBAL JUSTICE CLINIC (NYU SCHOOL OF LAW), LIVING UNDER DRONES: DEATH, INJURY, AND TRAUMA TO CIVILIANS FROM US DRONE PRACTICES IN PAKISTAN (September, 2012) TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I ABOUT THE AUTHORS III EXECUTIVE SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS V INTRODUCTION 1 METHODOLOGY 2 CHALLENGES 4 CHAPTER 1: BACKGROUND AND CONTEXT 7 DRONES: AN OVERVIEW 8 DRONES AND TARGETED KILLING AS A RESPONSE TO 9/11 10 PRESIDENT OBAMA’S ESCALATION OF THE DRONE PROGRAM 12 “PERSONALITY STRIKES” AND SO-CALLED “SIGNATURE STRIKES” 12 WHO MAKES THE CALL? 13 PAKISTAN’S DIVIDED ROLE 15 CONFLICT, ARMED NON-STATE GROUPS, AND MILITARY FORCES IN NORTHWEST PAKISTAN 17 UNDERSTANDING THE TARGET: FATA IN CONTEXT 20 PASHTUN CULTURE AND SOCIAL NORMS 22 GOVERNANCE 23 ECONOMY AND HOUSEHOLDS 25 ACCESSING FATA 26 CHAPTER 2: NUMBERS 29 TERMINOLOGY 30 UNDERREPORTING OF CIVILIAN CASUALTIES BY US GOVERNMENT SOURCES 32 CONFLICTING MEDIA REPORTS 35 OTHER CONSIDERATIONS -

There Are Various Ways of Sourcing Books to Read During the Lockdown

There are various ways of sourcing books to read during the lockdown. You may have borrowed a lot from the school library, or may have lots at home. I’ve listed a selection of suggested good reads: some brand new, some classics, some long, some short. I hope there will be a good selection, with something for everyone. I’ll send five more each week. Next to each book, I have shown its price on Amazon. Any classics should be able to be downloaded on to a Kindle App for free. It is possible to join Buckinghamshire Libraries from home: https://buckinghamshire.spydus.co.uk/cgi-bin/spydus.exe/MSGTRN/WPAC/JOIN from which you can download books using the Libby App: https://www.overdrive.com/apps/libby/?utm_origin=lightning&utm_page_genre=tout&u tm_list=meet_libby&utm_content=libby_tout_learnmore_06019018 This is another good way of accessing books for free. WEEK 1 RECOMMENDATIONS 1. Noughts and Crosses by Malorie lackman. 2001. https://www.amazon.co.uk/Noughts-Crosses-Book- ebook/dp/B0031RS5YC/ref=sr_1_1?crid=1U8RFQMEE056F&dchild=1&keywords= noughts+and+crosses+malorie+blackman&qid=1585734994&s=books&sprefix=n ought+and%2Cstripbooks%2C169&sr=1-1 A story of star-crossed young lovers caught up in an alternative reality, where the whites are the Nought underclass and Crosses are the powerful black rulers. When published, this book tackled discrimination in a way that no other book for teenagers had done before. It has recently been televised in a 6 part series: https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p082w992, but do make sure you read it before watching it to really get the full impact. -

See You in the USA

The Bureau of International Information Programs of the U.S. Department of State publishes a monthly electronic journal under the eJournal USA logo. These journals examine major issues facing the United States and the international community, as well as U.S. society, values, thought, and institutions. U.S. DEPARTMENT OF STATE / MAY 2010 VOLUME 15 / NUMBER 5 Twelve journals are published annually in English, http://www.america.gov/publications/ejournalusa.html followed by versions in French, Portuguese, Russian, and Spanish. Selected editions also appear in Arabic, Chinese, and Persian. Each journal is catalogued by volume and International Information Programs: number. Coordinator Daniel Sreebny The opinions expressed in the journals do not necessarily Executive Editor Jonathan Margolis reflect the views or policies of the U.S. government. The Director of Publications Michael Jay Friedman U.S. Department of State assumes no responsibility for the content and continued accessibility of Internet sites to which the journals link; such responsibility resides Editor-in-Chief Richard W. Huckaby solely with the publishers of those sites. Journal articles, Managing Editor Bruce Odessey photographs, and illustrations may be reproduced and Contributing Editor Nadia Shairzay translated outside the United States unless they carry Production Manager Janine Perry explicit copyright restrictions, in which case permission must be sought from the copyright holders noted in the Designer Chloe D. Ellis journal. The Bureau of International Information Programs Photo Editor Maggie Johnson Sliker maintains current and back issues in several electronic Cover Design Diane Woolverton formats, as well as a list of upcoming journals, at Graphics Designer Vincent Hughes http://www.america.gov/publications/ejournalusa.html. -

Sources of Lear

Meddling with Masterpieces: the On-going Adaptation of King Lear by Lynne Bradley B.A., Queen’s University 1997 M.A., Queen’s University 1998 A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in the Department of English © Lynne Bradley, 2008 University of Victoria All rights reserved. This dissertation may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photo-copying or other means, without the permission of the author. ii Meddling with Masterpieces: the On-going Adaptation of King Lear by Lynne Bradley B.A., Queen’s University 1997 M.A., Queen’s University 1998 Supervisory Committee Dr. Sheila M. Rabillard, Supervisor (Department of English) Dr. Janelle Jenstad, Departmental Member (Department of English) Dr. Michael Best, Departmental Member (Department of English) Dr. Annalee Lepp, Outside Member (Department of Women’s Studies) iii Supervisory Committee Dr. Sheila M. Rabillard, Supervisor (Department of English) Dr. Janelle Jenstad, Departmental Member (Department of English) Dr. Michael Best, Departmental Member (Department of English) Dr. Annalee Lepp, Outside Member (Department of Women’s Studies) Abstract The temptation to meddle with Shakespeare has proven irresistible to playwrights since the Restoration and has inspired some of the most reviled and most respected works of theatre. Nahum Tate’s tragic-comic King Lear (1681) was described as an execrable piece of dementation, but played on London stages for one hundred and fifty years. David Garrick was equally tempted to adapt King Lear in the eighteenth century, as were the burlesque playwrights of the nineteenth. In the twentieth century, the meddling continued with works like King Lear’s Wife (1913) by Gordon Bottomley and Dead Letters (1910) by Maurice Baring. -

CAMBRIDGE LIBRARY COLLECTION Books of Enduring Scholarly Value

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-00108-3 - The Bowdler Shakespeare, Volume 1 William Shakespeare Frontmatter More information CAMBRIDGE LIBRARY COLLECTION Books of enduring scholarly value Literary studies This series provides a high-quality selection of early printings of literary works, textual editions, anthologies and literary criticism which are of lasting scholarly interest. Ranging from Old English to Shakespeare to early twentieth-century work from around the world, these books offer a valuable resource for scholars in reception history, textual editing, and literary studies. The Bowdler Shakespeare ‘The Family Shakspeare: in which nothing is added to the original text, but those words and expressions are omitted which cannot with propriety be read in family.’ These words on the title pages of this edition gave rise to the verb ‘to bowdlerise’ - to remove or modify text which was considered vulgar or objectionable. Thomas Bowdler (1754-1825) was a man of independent means who studied medicine but, instead of practising as a doctor, devoted his time to prison reform, chess and the sanitising of Shakespeare. The first edition of the Family Shakespeare was published in 1818, and Bowdler’s work became enormously popular as the scandal-ridden Regency gave way to Victorian respectability. This volume, from the 1853 edition, contains The Tempest, Two Gentlemen of Verona, The Merry Wives of Windsor, Twelfth Night, Measure for Measure, Much Ado about Nothing and A Midsummer Night’s Dream. © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-00108-3 - The Bowdler Shakespeare, Volume 1 William Shakespeare Frontmatter More information Cambridge University Press has long been a pioneer in the reissuing of out-of- print titles from its own backlist, producing digital reprints of books that are still sought after by scholars and students but could not be reprinted economically using traditional technology. -

First Choice Monthly Newsletter WUSF

University of South Florida Scholar Commons First Choice Monthly Newsletter WUSF 1-1-2010 First Choice - January 2010 WUSF, University of South Florida Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/wusf_first Part of the Broadcast and Video Studies Commons Scholar Commons Citation WUSF, University of South Florida, "First Choice - January 2010" (2010). First Choice Monthly Newsletter. Paper 25. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/wusf_first/25 This News Article is brought to you for free and open access by the WUSF at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in First Choice Monthly Newsletter by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. firstchoice wusf for information, education and entertainment • JanuarY 2010 Carl Kasell Sleeps In After 30 years, the beloved NPR newscaster retires from Morning Edition For the past 30 years, Carl Kasell’s distinctive voice has informed listeners of the day’s top stories as the chief newscaster for NPR’s Morning Edition. After setting his alarm clock for 1 a.m. for all of those years, Kasell has finally decided to sleep in. Last month he hung up his microphone and retired from his newscaster responsibilities. A veteran broadcaster with a career spanning more than 50 years, Kasell became a part-time NPR newscaster in 1975, and joined the staff full-time in 1977. He did the first newscast of Morning Edition in 1979 and has been a fixture of the program ever since. To tens of thousands of NPR listeners, it was Kasell who broke the news of such gripping events as the fall of the Berlin Wall and the terrorist attacks of Sept 11, 2001. -

Lessons-Encountered.Pdf

conflict, and unity of effort and command. essons Encountered: Learning from They stand alongside the lessons of other wars the Long War began as two questions and remind future senior officers that those from General Martin E. Dempsey, 18th who fail to learn from past mistakes are bound Excerpts from LChairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff: What to repeat them. were the costs and benefits of the campaigns LESSONS ENCOUNTERED in Iraq and Afghanistan, and what were the LESSONS strategic lessons of these campaigns? The R Institute for National Strategic Studies at the National Defense University was tasked to answer these questions. The editors com- The Institute for National Strategic Studies posed a volume that assesses the war and (INSS) conducts research in support of the Henry Kissinger has reminded us that “the study of history offers no manual the Long Learning War from LESSONS ENCOUNTERED ENCOUNTERED analyzes the costs, using the Institute’s con- academic and leader development programs of instruction that can be applied automatically; history teaches by analogy, siderable in-house talent and the dedication at the National Defense University (NDU) in shedding light on the likely consequences of comparable situations.” At the of the NDU Press team. The audience for Washington, DC. It provides strategic sup- strategic level, there are no cookie-cutter lessons that can be pressed onto ev- Learning from the Long War this volume is senior officers, their staffs, and port to the Secretary of Defense, Chairman ery batch of future situational dough. The only safe posture is to know many the students in joint professional military of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and unified com- historical cases and to be constantly reexamining the strategic context, ques- education courses—the future leaders of the batant commands. -

What and Why Is High-Pop?

What and Why Is High-PPop? Or, What Would It Take to Get You into a New Shakespeare Today? Brian Cowlishaw A recent New Yorker film review observes wryly that lar is not "high," and that which is "high" is not terribly filmmakers, desperate for more Jane Austen novels to popular. (At least, comparatively speaking. People do film but having filmed them all to death, have now had pay, for example, to attend opera performances; but to resort to her life for material in Becoming Jane. It's gross ticket sales will never approach American Idol's true: an awful lot of Jane Austen films have been pro- moneymaking might.) It would therefore seem futile to duced in the last fifteen years. Not only that, they've bring to the popular market a work of high-pop, one been popular. Googleplex-goers just can't get enough based on something not especially popular to begin witty, romantic Regency banter. This is one prominent with. "Wagner's Greatest Hits" are still works com- current example of the phenomenon that is "high-pop"- posed by Wagner; they will never sell anything like "high culture" repackaged and resold as popular cul- "The Eagles' Greatest Hits" (the bestselling rock album ture. of all time). In a way, selling high-pop is like selling chocolate-covered ants from a mall kiosk: a select few The name "high-pop" comes from a 2002 book edited may gasp with delight over every one of the product's by Jim Collins, High-Pop: Making Culture into Popular fine qualities, but most people will not willingly give the Entertainment. -

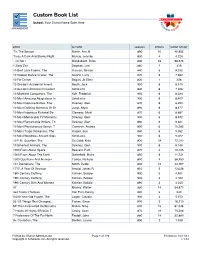

Custom Book List

Custom Book List School: Your District Name Goes Here MANAGEMENT BOOK AUTHOR LEXILE® POINTS WORD COUNT 'Tis The Season Martin, Ann M. 890 10 40,955 'Twas A Dark And Stormy Night Murray, Jennifer 830 4 4,224 ...Or Not? Mandabach, Brian 840 23 98,676 1 Zany Zoo Degman, Lori 860 1 415 10 Best Love Poems, The Hanson, Sharon 840 6 8,332 10 Coolest Dance Crazes, The Swartz, Larry 870 6 7,660 10 For Dinner Bogart, Jo Ellen 820 1 328 10 Greatest Accidental Inventi Booth, Jack 900 6 8,449 10 Greatest American President Scholastic 840 6 7,306 10 Mightiest Conquerors, The Koh, Frederick 900 6 8,034 10 Most Amazing Adaptations In Scholastic 900 6 8,409 10 Most Decisive Battles, The Downey, Glen 870 6 8,293 10 Most Defining Moments Of Th Junyk, Myra 890 6 8,477 10 Most Ingenious Fictional De Clemens, Micki 870 6 8,687 10 Most Memorable TV Moments, Downey, Glen 900 6 8,912 10 Most Remarkable Writers, Th Downey, Glen 860 6 9,321 10 Most Revolutionary Songs, T Cameron, Andrea 890 6 10,282 10 Most Tragic Romances, The Harper, Sue 860 6 9,052 10 Most Wondrous Ancient Sites Scholastic 900 6 9,022 10 P.M. Question, The De Goldi, Kate 830 18 72,103 10 Smartest Animals, The Downey, Glen 900 6 8,148 1000 Facts About Space Beasant, Pam 870 4 10,145 1000 Facts About The Earth Butterfield, Moira 850 6 11,721 1000 Questions And Answers Tames, Richard 890 9 38,950 101 Dalmatians, The Smith, Dodie 830 12 44,767 1777: A Year Of Decision Arnold, James R. -

By TERRY PRATCHETT

Discussion Guide By TERRY PRATCHETT ABOUT THE BOOK A young street urchin comes to the aid of a seemingly helpless young woman, beginning his meteoric ascent through London society as he rubs shoulders with the likes of Charles Dickens, Benjamin Disraeli, and Sweeney Todd. With his characteristic wit and boundless imagination, Terry Pratchett delivers a tale of London in the Victorian Age, and of a young man who must navigate its seamy underbelly—not just the ancient Roman sewers but the dangerous world of greed, crime, and politics. DISCUSSION QUESTIONS 1. Discuss a woman’s place in society during telling people that they are downtrodden, the Victorian Age. Cite evidence from the text, you tend to make two separate enemies. especially as it relates to Simplicity, Angela, Money makes people rich; it is a fallacy to think and the queen. How representative do you it makes them better, or even that it makes them think they are of typical Victorian women? worse. Responsibilities are the anvil on which a man is forged.” Can you spot others? 2. In this novel, one of the world’s greatest storytellers (Terry Pratchett) pays homage to 6. “ The iron forged on the anvil cannot be blamed another (Charles Dickens). Discuss several for the hammer,” says Solomon (page 182). ways that Pratchett does this. Do you agree? “Mister Todd killed, but he wasn’t a killer. Maybe if he’d never had to go 3. Names can reveal a lot about a character. to that blessed war, he wouldn’t have gone Do you think Dodger’s name suits him? right off his head,” thinks Dodger (page 281). -

Penguin Classics September 80

Penguin Books Penguin Pen g uin B o oks September – December 2009 P E N G U I N CLASSIC CLASSIC PENGUIN Penguin Books A member of Penguin Group (USA) Inc. A Pearson Company 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014 www.penguin.com ISBN: 9783001143303 Cover adapted from the original cover design by Roseanne Serra for Bacardi and the Long Fight for Cuba by Tom Gjelten (see p. 11.) Fall 2009 Credit: © Lake County Museum/Corbis Celebrate the inauguration of America’s 44th president with this New York Times bestseller Tying into the offi cial theme for the 2009 inaugural ceremony, “A New Birth of Freedom” from Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address, Penguin presents a keepsake edition commemorating the inauguration of President Barack Obama with words of the two great thinkers and writers who have helped shape him politically, philosophically, and personally: Abraham Lincoln and Ralph Waldo Emerson. Having Lincoln and Emerson’s most infl uential, memorable, and eloquent words along with Obama’s historic inaugural address will be a gift of inspiration for every American for generations to come. Includes: • Barack Obama, Inaugural Address, 2009 • Abraham Lincoln, Second Inaugural Address, 1865 • Abraham Lincoln, The Gettysburg Address, 1863 • Abraham Lincoln, First Inaugural Address, 1861 The Inaugural Address 2009 BARACK OBAMA • Ralph Waldo Emerson, Self-Reliance, 1841 ISBN 978-0-14-311642-4 $12.00 ($15.00 CAN) Nonfi ction 4 x 7 112 pp. Rights: DW Available Now A Penguin Hardcover Original Features a linen cover with gold-stamped lettering Also available as an e-book BARACK OBAMA became the fi rst African American to be elected President of the United States on November 4, 2008.