HAMADA Three Generations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

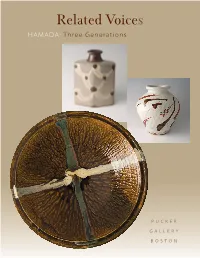

Related Voices Hamada: Three Generations

Related Voices HAMADA: Three Generations PUCKER GALLERY BOSTON Tomoo Hamada Shoji Hamada Bottle Obachi (Large Bowl), 1960-69 Black and kaki glaze with akae decoration Ame glaze with poured decoration 12 x 8 ¼ x 5” 4 ½ x 20 x 20” HT132 H38** Shinsaku Hamada Vase Ji glaze with tetsue and akae decoration Shoji Hamada 9 ¾ x 5 ¼ x 5 ¼” Obachi (Large Bowl), ca. 1950s HS36 Black glaze with trailing decoration 5 ½ x 23 x 23” H40** *Box signed by Shoji Hamada **Box signed by Shinsaku Hamada All works are stoneware. Three Voices “To work with clay is to be in touch with the taproot of life.’’ —Shoji Hamada hen one considers ceramic history in its broadest sense a three-generation family of potters isn’t particularly remarkable. Throughout the world potters have traditionally handed down their skills and knowledge to their offspring thus Wmaintaining a living history that not only provided a family’s continuity and income but also kept the traditions of vernacular pottery-making alive. The long traditions of the peasant or artisan potter are well documented and can be found in almost all civilizations where the generations are to be numbered in the tens or twenties or even higher. In Africa, South America and in Asia, styles and techniques remained almost unaltered for many centuries. In Europe, for example, the earthenware tradition existed from the early Middle Ages to the very beginning of the 20th century. Often carried on by families primarily involved in farming, it blossomed into what we would now call the ‘slipware’ tradition. The Toft family was probably the best known makers of slipware in Staffordshire. -

The Leach Pottery: 100 Years on from St Ives

The Leach Pottery: 100 years on from St Ives Exhibition handlist Above: Bernard Leach, pilgrim bottle, stoneware, 1950–60s Crafts Study Centre, 2004.77, gift of Stella and Nick Redgrave Introduction The Leach Pottery was established in St Ives, Cornwall in the year 1920. Its founders were Bernard Leach and his fellow potter Shoji Hamada. They had travelled together from Japan (where Leach had been living and working with his wife Muriel and their young family). Leach was sponsored by Frances Horne who had set up the St Ives Handicraft Guild, and she loaned Leach £2,500 as capital to buy land and build a small pottery, as well as a sum of £250 for three years to help with running costs. Leach identified a small strip of land (a cow pasture) at the edge of St Ives by the side of the Stennack stream, and the pottery was constructed using local granite. A tiny room was reserved for Hamada to sleep in, and Hamada himself built a climbing kiln in the oriental style (the first in the west, it was claimed). It was a humble start to one of the great sites of studio pottery. The Leach Pottery celebrates its centenary year in 2020, although the extensive programme of events and exhibitions planned in Britain and Japan has been curtailed by the impact of Covid-19. This exhibition is the tribute of the Crafts Study Centre to the history, legacy and continuing significance of The Leach Pottery, based on the outstanding collections and archives relating firstly to Bernard Leach. -

Bachelor of Science in Art History and Theory Thesis Reframing Tradition

Bachelor of Science in Art History and Theory Thesis Reframing Tradition in Modern Japanese Ceramics of the Postwar Period Comparison of a Vase by Hamada Shōji and a Jar by Kitaōji Rosanjin Grant Akiyama Submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirement for the degree of Bachelor of Science in Art History and Theory, School of Art and Design Division of Art History New York State College of Ceramics at Alfred University Alfred, New York 2017 Grant Akiyama, BS Dr. Hope Marie Childers, Thesis Advisor Acknowledgements I could not have completed this work without the patience and wisdom of my advisor, Dr. Hope Marie Childers. I thank Dr. Meghen Jones for her insights and expertise; her class on East Asian crafts rekindled my interest in studying Japanese ceramics. Additionally, I am grateful to the entire Division of Art History. I thank Dr. Mary McInnes for the rigorous and unique classroom experience. I thank Dr. Kate Dimitrova for her precision and introduction to art historical methods and theories. I thank Dr. Gerar Edizel for our thought-provoking conversations. I extend gratitude to the libraries at Alfred University and the collections at the Alfred Ceramic Art Museum. They were invaluable resources in this research. I thank the Curator of Collections and Director of Research, Susan Kowalczyk, for access to the museum’s collections and records. I thank family and friends for the support and encouragement they provided these past five years at Alfred University. I could not have made it without them. Following the 1950s, Hamada and Rosanjin were pivotal figures in the discourse of American and Japanese ceramics. -

Bernard Leach and British Columbian Pottery: an Historical Ethnography of a Taste Culture

BERNARD LEACH AND BRITISH COLUMBIAN POTTERY: AN HISTORICAL ETHNOGRAPHY OF A TASTE CULTURE by Nora E. Vaillant B. A. Swarthmore College, 1989 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF Master of Arts in The Faculty of Graduate Studies (Department of Anthropology and Sociology) We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard The University of British Columbia October 2002 © Nora E. Vaillant, 2002 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the head of my department or by his or her representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of J^j'thiA^^ The University of British Columbia Vancouver, Canada Date DE-6 (2/88) ABSTRACT This thesis presents an historical ethnography of the art world and the taste culture that collected the west coast or Leach influenced style of pottery in British Columbia. This handmade functional style of pottery traces its beginnings to Vancouver in the 1950s and 1960s, and its emergence is embedded in the cultural history of the city during that era. The development of this pottery style is examined in relation to the social network of its founding artisans and its major collectors. The Vancouver potters Glenn Lewis, Mick Henry and John Reeve apprenticed with master potter Bernard Leach in England during the late fifties and early sixties. -

Smithsonian Collections from Commodore Matthew Perry's Japan Expedition (1853-1854)

Artifacts of Diplomacy: Smithsonian Collections from Commodore Matthew Perry's Japan Expedition (1853-1854) CHANG-SU HOUCHINS SMITHSONIAN CONTRIBUTIONS TO ANTHROPOLOGY • NUMBER 37 SERIES PUBLICATIONS OF THE SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION Emphasis upon publication as a means of "diffusing knowledge" was expressed by the first Secretary of the Smithsonian. In his formal plan for the institution, Joseph Henry outlined a program that included the following statement: "It is proposed to publish a series of reports, giving an account of the new discoveries in science, and of the changes made from year to year in all branches of knowledge." This theme of basic research has been adhered to through trie years by thousands of titles issued in series publications under the Smithsonian imprint, commencing with Smithsonian Contributions to Knowledge in 1848 and continuing with the following active series: Smithsonian Contributions to Anthropology Smithsonian Contributions to Botany Smithsonian Contributions to the Earth Sciences Smithsonian Contributions to the Marine Sciences Smithsonian Contributions to Paleobiology Smithsonian Contributions to Zoology Smithsonian Folklife Studies Smithsonian Studies in Air and Space Smithsonian Studies in History and Technology In these series, the Institution publishes small papers and full-scale monographs that report the research and collections of its various museums and bureaux or of professional colleagues in the world of science and scholarship. The publications are distributed by mailing lists to libraries, universities, and similar institutions throughout the world. Papers or monographs submitted for series publication are received by the Smithsonian Institution Press, subject to its own review for format and style, only through departments of the various Smithsonian museums or bureaux, where the manuscripts are given substantive review. -

Leach Pottery Announce Collaborative Project to Restore Documentary Film Compendium on Bernard Leach and the Mingei Movement

Leach Pottery Announce Collaborative Project to Restore Documentary Film Compendium on Bernard Leach and the Mingei Movement The Leach Pottery and Marty Gross Film Productions, Canada, announce their collaboration in the restoration and re-release of historically important films from the 1930’s to the 1970’s which profile key figures in the history of The Leach Pottery and the Japanese Mingei Movement. The Great Britain Sasakawa Foundation have provided a generous £5000 donation in support of this unique project, and following this initial funding further funding has been pledged or received from The Museum of Ceramic Art New York, Ceramica Stiftung Basel, Warren and Nancy MacKenzie, scholar Dr. Paul Griffith and art collector Dr. John Driscoll. Film subjects include Bernard Leach, Shoji Hamada, Soetsu Yanagi, Janet Leach, William Marshall and others. Bernard Leach, founder of The Leach Pottery, was an important figure in the history of contemporary ceramics and a key member of the group that founded the Mingei Movement. His writings on Japan and its ceramic traditions are central documents in the history of the Modern craft movement. Over the neXt three years, the project will restore and digitize important and never before seen footage which documents the studies of Bernard Leach and his colleagues in Japan as they developed ideas that became central to the Mingei movement. The resulting compendium will consist of DVDs and a booklet containing the following films and new documentation: ▪ Trip to Japan, filmed by Bernard Leach, 1934-35 ▪ Mashiko Village Pottery, Japan 1937 ▪ Bernard Leach visit to San Francisco, 1950 ▪ The Art of the Potter (1971), by David Outerbridge and Sidney Reichman ▪ Excerpts from 10 hours of unseen film footage from The Art of the Potter ▪ An exclusive Video Interview by Marty Gross with Mihoko Okamura, D.T. -

A Potters Book Free Ebook

FREEA POTTERS BOOK EBOOK Bernard Leach | 372 pages | 23 Feb 2012 | FABER & FABER | 9780571283675 | English | London, United Kingdom A Potter's Book Harry Potter is a series of seven fantasy novels written by British author J. K. Rowling. The novels chronicle the lives of a young wizard, Harry Potter, and his friends Hermione Granger and Ron Weasley, all of whom are students at Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry. A Potter's Book by Bernard Leach with introductions by Soyetsu Yanagi and Michael Cardew. This is the first treatise by a potter on the workshop traditions which have been handed down by Koreans and Japanese from the greatest period of Chinese ceramics in the Sung dynasty. This now famous book was the first treatise to be written by a potter on the workshop traditions handed down by Koreans and Japanese from the greatest period of Chinese ceramics in the Sung dynasty. It deals with four types of pottery: Japanese raku, English slipware, stoneware and oriental porcelain. Potters Book by Leach Bernard A Potter Book by Bernard Leach. Topics IIIT Collection digitallibraryindia; JaiGyan Language English. Book Source: Digital Library of India Item In A Potter's Workbook, renowned studio potter and teacher Clary Illian presents a textbook for the hand and the mind. Her aim is to provide a way to see, to make, and to think about the forms of wheel-thrown vessels; her information and inspiration explain both the mechanics of throwing and finishing pots made simply on the wheel and the principles of truth and beauty arising from that traditional method. -

THE LEACH POTTERY: ONE CENTURY Dates: 17Th

THE LEACH POTTERY: ONE CENTURY Dates: 17th Jan - 14th March 2020 Private View: Friday 17th Jan / 5-7pm Oxford Ceramics opens its 2020 season by celebrating the centenary of one of the most significant ceramic studios of the modern era: the Leach Pottery, founded in 1920. This pottery has shaped studio ceramics as we know it today, and is a cornerstone of ceramic history. It includes over 200 works sourced from across the globe from these masters of ceramics: Bernard Leach, Shoji Hamada, Michael Cardew, Kawai Kanjiro, and Tomimoto Kenkichi; as well as antique English slipware from as far back as the 18th century. This is a show that weaves together both influence and the finished article. There is something for the collector, ceramic enthusiasts and the plain curious. “As far back as one goes in time, the works of humanity from prehistoric times have reached us not through stone which crumbles and wears away, or through metal which oxidizes and becomes like powder, but through slabs of pottery, the writing on which is as clear today as it was under the stiletto of the scribe who traced it.” (Bernard Leach, A Potter's Book) James Fordham, the creative director of Oxford Ceramics, says, “This was always going to be a significant show for the gallery, as the Leach Pottery is one of the most respected and influential potteries in the world. I wanted to mark this anniversary with a show that explored not only the work of Leach & Hamada, but that looked deeper into the influences on their work.” Many great potters studied under Leach and many more were inspired by his written work, including A Potter’s Book, published in 1940. -

Masterpieces of Modern Studio Ceramics

Masterpieces of Modern Studio Ceramics Ceramics is having a bit of a moment. Last year alone featured exhibitions such as: Things of Beauty Growing: British Studio Pottery at the Yale Center for British Art, opening at The Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, this March, That Continuous Thing at Tate St Ives, Clare Twomey’s Factory installation take-over at Tate Exchange, Keith Harrison’s Joyride spectacle for Jerwood Open Forest Commission, as well as the incredibly successful British Ceramics Biennale, Stoke-on-Trent. The profile of British studio ceramics is growing, presenting the perfect opportunity to celebrate the relationship between studio ceramic practice and British modernism. Beginning in the early 20th century, the British studio ceramics movement reinvigorated a long- standing tradition of making objects from clay, by hand. These objects span familiar forms, such as domestic functional vessels, to abstract and non-functional, often sculptural, forms. Sitting at the heart of Crafts Council Collections, British studio ceramics provide a cross-generational narrative of innovation, invention and tradition. Featuring works from the Crafts Council, The Fitzwilliam Museum and three specialist UK galleries, this display presents nearly 90 years of practice, and features functional, sculptural, abstract and figurative forms, presenting a snapshot of work and makers to inspire. Annabelle Campbell and Helen Ritchie (curators) THE GALLERIES: Erskine Hall and Coe Marsden Woo Gallery Oxford Ceramics Gallery 15 Royal Arcade 229 Ebury Street 29 -

As I Was Going to St Ives… LIVING a TRADITION at the LEACH POTTERY

ARTS & CULTURE As I was going to St Ives… LIVING A TRADITION AT THE LEACH POTTERY It’s a long way from the tourist fray and the packed summertime Leach in St Ives between 1949 and 1952. Portland, Oregon- beaches that so many people associate with St Ives, Cornwall based potter Carson Culp finished up as a volunteer studio assis - and that’s part of the beauty of the place. Far from the seafront, tant in 2017, and he is currently resident artist at the Museum with its innumerable galleries, craft shops and cafes lies the of Ceramic Art in the legendary pottery town of Mashiko, Leach Pottery, a bastion of tranquillity and East Asian sensibility. Japan. He, too, is captivated by the many historic connections Created by Bernard Leach (1887-1979), the esteemed English between Leach and Mashiko, where Leach first encountered the studio potter, (and widely acknowledged as the most influential master potter, Shoji Hamada (1894-1978). potter of the 20th century), it was from the small studio on Consisting of a museum, gallery, studio and shop packed with Higher Stennack in St Ives that Leach contributed so much to locally made pots, the Leach Pottery is an absolute must-see in artistic sensitivity, both in Britain and in the wider world. Cornwall, and it can easily serve as the focal point to include a Although a Sunday afternoon drive past the Leach Pottery look around other centres of artistic production, past and pres - wouldn’t immediately call all this to mind, just one glance at the ent, in St Ives. -

Influence of British Pottery on Pottery Practice in Nigeria

EJERS, European Journal of Engineering research and Science Vol. 4, No. 6, June 2019 Influence of British Pottery on Pottery Practice in Nigeria Edem E. Peters and Ruth M. Gadzama though after obtaining his degrees from Oxford went to Abstract—The pottery narratives of Nigeria majorly linked study Pottery under Bernard Leach (English) and Hamada a with the activities of a great British potter Michael Cardew Japanese expand at St. Ives. He spent greater part of active who Established pottery centres in Nigeria, and trained many years of his pottery practice in Nigeria from about 1950. His Nigerians in Pottery. Cardew studied under Bernard Leach twenty-three years Pottery experience at Abuja in Nigeria as (1887 – 1979) who travels extensively and taught pottery around the world.Leach studied pottery under Master Kenzan Pottery Officer brought about training numerous men and VI in Japan and returned to England in 1920 to establish his women on the British Pottery. Indigenous potters especially own pottery at St. Ives with Shoji Hamada. The impact in the women were encouraged and protected from pottery created by Cardew in Nigeria from 1950 is a direct exploitation. Pottery training centres were established and British Pottery influence imparted to him by leach at St. Ives. Potters’ raw materials were identified and sourced for local A British potter and artist, Kenneth C. Murray studied pottery use during Cardew stay in Nigeria. Nigeria had and still has under Bernard Leach at St. Ives in 1929 and returned back to Uyo in Nigeria to produce and teach students pottery. Murray very rich pottery tradition before Cardew came to start the produced pottery wares from the Kiln he built at Uyo and took pottery training centres. -

Bernard Leach

BERNARD LEACH hsgayg in Appreciofiiom CoiiectedF ané Edited by T. Barrow A Monograph published by the Editorial Committee of the N.Zi Potter Wellington New Zealand 1960 BERNARD LEACH READING — ST.IVES, 1957 CONTENTS Page List of Illustrations Terry Barrow Editorial Preface Bernard Leach An Open Letter to New O\ Zealand Potters The publication of this book was Bernard Leach Looking Backwards and made possible by the generosity of 10 the Hon. W. T. Anderton, Minister Forwards at 72 of Internal Affairs. Financial C. L. Bailey Bernard Leach in Perspective 16 support was also received by small donations and pre—publication Michael Cardew Bernard Leach — Recollections 19 payment of subscriptions. All Ray Chapman—Taylor A Few Lines on Bernard Leach 26 work in connection with the pro— duction of this book has been Kathe rine Pleydell — At St. Ives in the Early Years 29 voluntary, and any profits from Bouverie its sale will be used to subsidize Barry Brickell The Colonial Response to Leach 33 regular issues of the N. Z. Potter Bernard Leach A Note on Japanese Tea 37 or other monographs. Ceremony Wares Len Castle Photographs of the Leach 39 Mr. Wilf Wright has generously Pottery undertaken the task of distributing Murray Fieldhouse Workshop Visit - The Leach 41 the book. Copies may be obtained Pottery for ten shillings each by applying to Mr. Wright at Stockton's Ltd. , George Wingfieldu Bernard Leach — Bridge between Woodward Street, Wellington, N. Z. Digby East and We st Bernard Howell Leach Biographical Chronology 62 c 1960 by the Editorial Committee N. Z.