Ceramics Monthly Jja19 Cei061

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

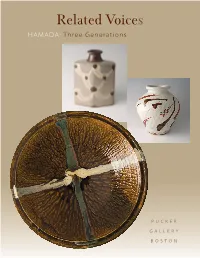

Related Voices Hamada: Three Generations

Related Voices HAMADA: Three Generations PUCKER GALLERY BOSTON Tomoo Hamada Shoji Hamada Bottle Obachi (Large Bowl), 1960-69 Black and kaki glaze with akae decoration Ame glaze with poured decoration 12 x 8 ¼ x 5” 4 ½ x 20 x 20” HT132 H38** Shinsaku Hamada Vase Ji glaze with tetsue and akae decoration Shoji Hamada 9 ¾ x 5 ¼ x 5 ¼” Obachi (Large Bowl), ca. 1950s HS36 Black glaze with trailing decoration 5 ½ x 23 x 23” H40** *Box signed by Shoji Hamada **Box signed by Shinsaku Hamada All works are stoneware. Three Voices “To work with clay is to be in touch with the taproot of life.’’ —Shoji Hamada hen one considers ceramic history in its broadest sense a three-generation family of potters isn’t particularly remarkable. Throughout the world potters have traditionally handed down their skills and knowledge to their offspring thus Wmaintaining a living history that not only provided a family’s continuity and income but also kept the traditions of vernacular pottery-making alive. The long traditions of the peasant or artisan potter are well documented and can be found in almost all civilizations where the generations are to be numbered in the tens or twenties or even higher. In Africa, South America and in Asia, styles and techniques remained almost unaltered for many centuries. In Europe, for example, the earthenware tradition existed from the early Middle Ages to the very beginning of the 20th century. Often carried on by families primarily involved in farming, it blossomed into what we would now call the ‘slipware’ tradition. The Toft family was probably the best known makers of slipware in Staffordshire. -

Smithsonian Collections from Commodore Matthew Perry's Japan Expedition (1853-1854)

Artifacts of Diplomacy: Smithsonian Collections from Commodore Matthew Perry's Japan Expedition (1853-1854) CHANG-SU HOUCHINS SMITHSONIAN CONTRIBUTIONS TO ANTHROPOLOGY • NUMBER 37 SERIES PUBLICATIONS OF THE SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION Emphasis upon publication as a means of "diffusing knowledge" was expressed by the first Secretary of the Smithsonian. In his formal plan for the institution, Joseph Henry outlined a program that included the following statement: "It is proposed to publish a series of reports, giving an account of the new discoveries in science, and of the changes made from year to year in all branches of knowledge." This theme of basic research has been adhered to through trie years by thousands of titles issued in series publications under the Smithsonian imprint, commencing with Smithsonian Contributions to Knowledge in 1848 and continuing with the following active series: Smithsonian Contributions to Anthropology Smithsonian Contributions to Botany Smithsonian Contributions to the Earth Sciences Smithsonian Contributions to the Marine Sciences Smithsonian Contributions to Paleobiology Smithsonian Contributions to Zoology Smithsonian Folklife Studies Smithsonian Studies in Air and Space Smithsonian Studies in History and Technology In these series, the Institution publishes small papers and full-scale monographs that report the research and collections of its various museums and bureaux or of professional colleagues in the world of science and scholarship. The publications are distributed by mailing lists to libraries, universities, and similar institutions throughout the world. Papers or monographs submitted for series publication are received by the Smithsonian Institution Press, subject to its own review for format and style, only through departments of the various Smithsonian museums or bureaux, where the manuscripts are given substantive review. -

Wood-Fired Utilitarian Ware for Serving Japanese and American Food

Abstract Wood-Firing in America: Wood-Fired Utilitarian Ware for Serving Japanese and American Food by Yu Ishimaru July 2011 Director of Thesis: Jim Tisnado School of Art and Design In this body of work, my focus is on the surface and color of wood-fired ergonomic utilitarian ware. The natural-ash glazed surface and soft color changes from the atmospheric nature of wood firing are the principle aim of my firing. I intend for my wood fired work to be used on the table, in the kitchen, and around the home in both the United States and Japan on a daily basis. Food cultures between the United States and Japan are very different, and the ware used in both cultures is not the same, but similar. By approaching both food cultures from the similarities, I can be aware of the needs in the ware to be used in both food cultures. The surface and subtle color variation in my wood-fired work accompany the colors of both Japanese and American food presented at the table. Wood-fired work can be suitable for serving cross-cultural foods. WOOD-FIRING IN AMERICA: WOOD-FIRED UTILITARIAN WARE FOR SERVING JAPANESE AND AMERICAN FOOD A Report of a Creative Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the School of Art and Design East Carolina University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Fine Arts in Ceramics by Yu Ishimaru July 2011 ©Yu Ishimaru, July 2011 WOOD-FIRING IN AMERICA: WOOD-FIRED UTILITARIAN WARE FOR SERVING JAPANESE AND AMERICAN FOOD by Yu Ishimaru APPROVED BY: DIRECTOR OF THESIS:______________________________________________________________________ -

Japanese Painters' Pottery and Paintings

Oranda Jin Japanese painters' pottery and paintings ORANDA JIN Japanese paintings & painters’ pottery Jon & Senne de Jong orandajin.com Voor mijn lief, voor Marleen Short introduction Marleen, my wife, Senne’s mother, started the looking at artists, most of them unknown in the In the art historical field, the history of Japanese on the island of Kyūshū, especially known in the ceramics branch of Oranda Jin. West, from a reversed perspective, we found some potteries and their produce somehow still seems a West for the blue and white porcelain that was so During one of our visits to Japan, she told me she of them amazingly good and interesting. matter for the specialist, which is a shame, because popular in the Netherlands of the seventeenth and would like to have something to do herself, instead Japan has a rich ceramic tradition: from the mag- eighteenth century. Kyōyaki or kyō ware comes from of following me hunting scrolls. This made her feel Most painters’ ceramics were produced for the tea nificent pots that were already made during the the city of Kyoto and includes a wide variety of over like a dog she said – what does that say about me? ceremony, for special occasions, or in commemora- Jōmon period (– BCE) up until Japanese glazed stoneware that dates back to the eighteenth In line with our regular specialisation, she decided to tion of events and persons. This is why they are so ceramic art today. And sometimes a very special century. Bizen ware belongs to the group of red and look for pottery decorated or made by painters. -

Inuit Ceramics Tech: Rapid Bisque Firing Clay Culture: Sonoma Ash Project “I’D Rather Switch Than Fight.”

Cover: A. Blair Clemo Review: Inuit Ceramics Tech: Rapid Bisque Firing Clay Culture: Sonoma Ash Project “I’d rather switch than fight.” Find out why experienced potters are switching to L&L rather than fighting with their kilns. L&L Kiln’s patented hard ceramic element holders protect your kiln. hotkilns.com/why KILNS BUILT TO LAST 505 Sharptown Road • Swedesboro, NJ 08085 Phone: 800-750-8350 • Fax: 856.294.0070 Email: [email protected] • Web: hotkilns.com Bailey Kilns at Lillstreet Art Center The Lillstreet Art Center is the premiere ceramic center in Chicago. They support the ceramic arts through many avenues: an artist residen- cy program, gallery, studio space, education, and outreach program. After 28 years, they moved into a new state-of-the-art facility in 2003. It’s spacious and serves as the perfect environment to inspire. In their new facility, they selected Bailey Kilns to meet the rigorous firing demands of their active program that serves 500 students per term. Their kiln room houses two Bailey 2-Car Trackless PRO 54 cu.ft. kilns. Each kiln has been fired over 1200 times! The 2-Car track- less design gives their program great flexibility in their firing requirements. Because they chose the 2-car design, they are firing one load while the next is being prepared on the mobile trackless car. As soon as the fired load is cool, out it comes and in goes the next load. Seamless efficiency. Beyond stacking and cycling efficiency, there is the maximum fuel efficiency. Lillstreet appreciates all the savings in fuel. -

A Modern Approach to Tradition 9

Part 1 A MODERN APPROACH TO TRADITION 9 Design sources Introduction Today’s makers and designers draw on a rich history of pottery and industrial design for ideas, and there is greater awareness today of the different design traditions. One of the aims of this book is to bring together a number of different strands which have influenced contemporary tableware design. 1Handmade tableware of art. The resulting pots are often too expensive to use and During the Sung dynasty (AD 960–1279), the Chinese In the 19th century, at the end of the Industrial end up sitting on a shelf, while the humble handmade mug were the first to make durable, mass-produced porcelain Revolution, John Ruskin and William Morris criticised or bowl continues to be used every day. This book aims to tableware and by the 16th century were exporting it industrially produced wares and inspired the Arts and showcase the work of those potters who are committed to around the world. The Japanese adapted pottery-making Crafts movement. They proposed a return to hand-crafted making tableware. techniques from China and Korea and added their decorative arts, which should be both beautiful and own unique character from the 16th century onwards. useful. The concept of the handmade object being made Changing habits Meanwhile in post-medieval Europe, a rustic style available to all was raised again in the 20th century by Naturally, changing attitudes and habits in food of country pottery was evolving, which ended with potter Bernard Leach, who established the studio pottery preparation and service and the rituals of mealtimes the Industrial Revolution. -

1 a 149 Temperatura: 28, Núm

Acosta, Fátima: 14, núm. 50; 51, Agustdottir, Ragnheidur: 29, núm. Revista Cerámica núm. 53. 56. Acuarela sobre porcelana: 79, Ahlmann, Paul: 19, núm. 103. núm. 138. Ai Kyu, Hahn: 84, núm. 58. Índice General Adaptación de un esmalte: 79, Aichi, Expo, Cumella, 98, núm. núm. 49. 100. Adhesivos inorgánicos para alta Aida, Yusuke: 16, núm. 33. Núms. 1 a 149 temperatura: 28, núm. 46; 23, Aigua i Pols de Tarraco: 91, núm. núm. 67. 68. Adhesivos para cerámica: 25, Ailincai, Arina: 42, núm. 11, 72, núm. 43. 36, núm. 49 núm. 135. A Glazed Leaf: 8, núm. 51; 29, Adi, Edith: 87, núm. 61. Aislamiento: 28, núm. 1, con núm. 54. Adiciones de barro: 59, núm. 9. fibra: 52, núm. 21 Aaberg, Gunhild: 85, núm. 111. Adjiman, Violette: 41, núm. 48. Ajenjo, Vicente: 92, núm. 133. Aalto, Riitta: 7, núm. 49. Adobes, casas de, libro: 82, núm. Akabane, Pierre: 5, núm. 61. Abba, Irit: 29, núm. 39. 34; 69, núm. 44. Aki Matsui, Toshio: 25, núm. 14. Abbaye aux Dames, Bienal: 91, Adomonis, Andrius: 17, núm. 63. Akins, Lee: 18, núm. 132. núm. 54. Aduana, Concurso: 27, núm. 47; Akiyama, Yoh: 51, núm. 36; 11, Abbondanza, Jorge: 84, núm. 8, núm. 45. núm. 43; 8, núm. 95; 1 y 21, 110. AeCC en La Rambla: 81, núm. 98; 33, núm. 101, 6, ABC Terra: 36, núm. 70. núm.127. núm. 119, 88, núm. 144. Abel.Kremer, Sybille: 17, núm. Aerogel de sílice: 70, núm. 53. Akkerman, Teresa: 6, núm. 104. 135. Aerografía en cerámica de Aksjonova, Valentina, Letonia Abello, Joan (textos): 79, núm. -

Mingei Treasures

24 HAMADA SHOJI MINGEI TREASURES PUCKER GALLERY • BOSTON 24 HAMADA SHOJI HAMADA SHŌJI OBACHI (LARGE BOWL), Black glaze with poured decoration 5 ½ x 23 x 23” H40 Cover: HAMADA SHŌJI BOWL, Green glaze with poured decoration 4 ½ x 18 x 18” H42 ALL WORKS ARE STONEWARE 3 HAMADA SHOJI MINGEI CERAMICS: TRANSFORMING TRADITION hat is mingei, the “art of the ity to fi nd beauty in unexpected places, and this enabled him people?” Th e term was coined to assemble an amazing array of handmade utilitarian products, in 1925 by the Japanese philoso- including furniture, textiles, woodwork, metalwork, and espe- pher and aesthetician Yanagi Sōetsu cially ceramics. It is not surprising, then, that the close group of W(1889-1961) as a contraction of the friends that he gathered around him included many pott ers term minshu kōgei, or “industrial arts of who later became prominent advocates of the Mingei Move- the people.” In creating the word mingei Yanagi was building ment, among them Hamada Shōji (1894-1978), Kawai Kanjirō upon the work of the English thinkers John Ruskin (1819-1900) (1890-1966), and the Englishman Bernard Leach (1887-1979). and William Morris (1834-1896), who abhorred the eff ects of Th ese men understood Yanagi’s vision, and his infl uence had industrialization on the quality and design of manufactured a tremendous impact on their careers. Th us it came that the goods. Like Ruskin and Morris, Yanagi embraced the manual Mingei Movement was transformed from an exercise of simply labor of handicraft as essential to the creation of useful items evaluating and appreciating what already existed in Japan’s folk endowed with honesty and vigor. -

HAMADA Three Generations

HAMADA Three Generations PUCKER GALLERY • BOSTON 2 Shoji Hamada Shinsaku Hamada Lidded Bowl Bottle tenmoku and white poured decoration black and white glaze 6 x 7 ¾ x 7 ¾" 8 x 6 ¼ x 4 ¼" H11 HS8 Tomoo Hamada Shinsaku Hamada Vase Jar blue and kaki glaze with akae decoration salt glaze 9 ½ x 9 ½ x 6 ¼" 7 ½ x 7 ¼ x 7 ¼" HT21 HS6 3 Three Generations of HAMADA POTTERS f all the well-known Japanese ceramic art- holistic manner, and that his workshop, house, clothes, ists of the past four hundred years, men and lifestyle were all related to his greater motivation for like Raku ware’s Chojiro, the Kyoto design- working in clay. One is struck most strongly by both his ers and decorators Nonomura Ninsei and aesthetic focus and the reverence with which he treated OOgata Kenzan, and the innovative and technically brilliant his profession. These, and a keen sense of design, are Makuzu Kozan, by far the most famous and infl uential has what set Hamada Shoji apart from other ceramists. been the twentieth-century folk craft (mingei) movement Hamada Shoji’s son, Shinsaku, naturally has had a life potter Hamada Shoji (1894-1978). It is ironic that Shoji both easier and more diffi cult than his father. One might sought to capture the spirit of “nameless potters” (mumei suppose that growing up watching his father, then working toko) who had worked before him, and ended up becoming alongside him well into adulthood, it would take Shinsaku famed around the developed world. It is even more surpris- little effort to produce whatever he wanted.