Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nieuws Over Corona Afsluiting Van De Hoef Oostzijde Op 14 En 15 Juli

Gemeentenieuws GEMEENTEHUIS Werkzaamheden Bezoekadres Mijdrecht, gedeeltelijke wegafsluiting Anselmusstraat Nieuws over corona Croonstadtlaan 111 De Anselmusstraat is ter hoogte van huisnummers 23-29 van 14 juli 7.00 uur t/m 21 juli 17.00 uur Kijk op www.derondevenen.nl/corona 3641 AL Mijdrecht gedeeltelijk afgesloten. De gedeeltelijke afsluiting zal worden geregeld met verkeerslichten. Het voor het laatste nieuws Postadres verkeer kan passeren maar houd u rekening met een langere reistijd. De gemeente informeert u over de Postbus 250 Deze maatregel is nodig omdat GroenWest aan Coen Hagen Utrecht opdracht heeft gegeven ontwikkelingen rondom het coronavirus. 3640 AG Mijdrecht om groot onderhoud te verrichten aan 39 woningen in Mijdrecht. Kijk hiervoor op www.derondevenen.nl/ Contactgegevens Heeft u nog vragen? Op werkdagen kunt u tussen 8.00 en 16.30 uur contact opnemen met de corona T. 0297 29 16 16 | F. 0297 28 42 81 heer R. Keulen van Coen Hagedoorn Utrecht via 088 – 880 80 00. E. [email protected] Vragen over het coronavirus of Website Vinkeveen, tijdelijke afsluiting parkeerplaatsen Vinkenkade vaccinatie? www.derondevenen.nl De parkeerplaatsen aan de Vinkenkade ter hoogte van huisnummer 15 zijn van 12 juli 7.00 uur U kunt terecht bij Volg de gemeente op Facebook t/m 14 juli 16.00 uur afgesloten. In verband met de werkzaamheden vragen wij u vriendelijk • het RIVM: www.rivm.nl/coronavirus facebook.com/derondevenen deze dagen hier niet te parkeren. • de GGD regio Utrecht: instagram.com/gemeentedrv Deze maatregel is nodig in verband met het plaatsen van een hoogwerker voor werkzaamheden www.ggdru.nl/corona of twitter.com/gemeentedrv aan een telecommast. -

Apollo Hotel Vinkeveen Amsterdam

FACTS • NEXT TO THE A2 AND LAKES OF VINKEVEEN • 1,300 M2 CONFERENCE AREA • 170 PARKING SPACES • 86 LUXURY ROOMS • CATERING BY THE HARBOUR CLUB • 12 MINUTES FROM AMSTERDAM • 15 MINUTES FROM SCHIPHOL JAGUAR:‘THERE PROBABLY ISN’T A SHOWROOM ANYWHERE ELSE IN THE WORLD WITH A NICER VIEW, NAMELY THE IDYLLIC LAKES OF VINKEVEEN.’ APOLLO HOTEL VINKEVEEN-AMSTERDAM EVENT CENTRE VINKEVEEN CONTENT: • Event Centre Vinkeveen page 6 • Capacities per room page 7 • Conference arrangements page 9 We are the newest hotel of the Apollo Hotels. APOLLO HOTELS • Parties & Drinks page 14 Apollo Hotel Vinkeveen-Amsterdam provides Apollo Hotels guarantees precious moments, • Our facilities page 21 the perfect combination of green surroundings in the most beautiful cities in the Netherlands. • Audiovisual equipment page 26 and city with a view over the Lakes of Vinkeveen. We are certain that your stay will be unforgettable; • Partners page 29 Yet Amsterdam is still only 12 minutes away by whether you have to attend a meeting that • Overnight accommodation page 30 car. In our own harbour, we have 29 moorings requires your full concentration or if you arrive • Vink page 35 available. at the hotel late. We do everything to make sure • The Harbour Club Vinkeveen page 36 • Surroundings page 38 that you’ll be back. • Fire regulations page 40 Are you looking for a special venue for your • Practical information page 42 event? Event Centre Vinkeveen impresses with Apollo Hotels, YOU’LL BE BACK. • Directions & Parking page 44 boldness and creativity. Our brand-new Event Centre Vinkeveen, situated next to Apollo Hotel Vinkeveen-Amsterdam, is the perfect location. -

Baambrugse Zuwe En Vinkenkade Weer Open Voor Personenauto's

Tel: 0297-581698 Fax: 0297-581509 Editie: Mijdrecht, Wilnis, Vinkeveen 12 augustus 2009 2 GOED GEVOEL! “Ik heb een hypotheek gekregen, die perfect bij me past.” Stefanie de Ridder, Mijdrecht Safari? Beleef met de experts een exclusieve droomreis naar oost- of zuidelijk Afrika. Communicatieweg 11a Mijdrecht Telefoon 0297-254455 www.bms-travellers.nl FINANCIËLE DIENSTEN MIJDRECHT Bel 0297 27 30 37 of kom langs op het Burg. Haitsmaplein 29 in Mijdrecht Op de foto v.l.n.r: Maurice, Artienne, Bas - de eigenaar van de supermarkt die de bloemen in ontvangst nam voor Re- mon, en geheel rechts locoburgemeester Dekker. Korver Makelaars O.G. B.V. Stationsweg 12, 3641 RG Mijdrecht Drie werknemers van Super de Boer verijdelen overval Locatie: tegenover het gemeentehuis “Ik zag een man zitten met een bivakmuts op en dacht GEVONDEN: dat klopt niet” Auto Berkelaar Mijdrecht B.V. Vinkeveen - Door het kordate op- foon bij je? 112 bellen, want dit klopt drie bossen bloemen kwam brengen treden van drie werknemers van Su- niet’. In die tussentijd zagen we een voor de drie oplettende werknemers: Genieweg 50 Bouwerij 75 per de Boer uit Vinkeveen is er vrij- tweede man uit de bosjes stappen “Je moet er toch niet aan denken wat 3641 RH Mijdrecht 1187 XW Amstelveen dagochtend 7 augustus jl, hoogst- met een zwarte tas en gezamenlijk er had kunnen gebeuren”, besluit de 0297-282929 020-6401199 waarschijnlijk een overval op de Su- liepen ze, heel rustig, net of er niks locoburgemeester. per voorkomen. aan de hand was, het bruggetje over Dat de twee iets van plan waren is www.autoberkelaar.nl Als eerste kwam vrijdagochtend naar de Meerkoetlaan.” wel duidelijk. -

Just the Right Song at Just the Right Time Music Ideas for Your Celebration Chart Toppin

JUST THE RIGHT SONG AT CHART TOPPIN‟ 1, 2 Step ....................................................................... Ciara JUST THE RIGHT TIME 24K Magic ........................................................... Bruno Mars You know that the music at your party will have a Baby ................................................................ Justin Bieber tremendous impact on the success of your event. We Bad Romance ..................................................... Lady Gaga know that it is so much more than just playing the Bang Bang ............................................................... Jessie J right songs. It‟s playing the right songs at the right Blurred Lines .................................................... Robin Thicke time. That skill will take a party from good to great Break Your Heart .................................. Taio Cruz & Ludacris every single time. That‟s what we want for you and Cake By The Ocean ................................................... DNCE California Girls ..................................................... Katie Perry your once in a lifetime celebration. Call Me Maybe .......................................... Carly Rae Jepson Can‟t Feel My Face .......................................... The Weeknd We succeed in this by taking the time to get to know Can‟t Stop The Feeling! ............................. Justin Timberlake you and your musical tastes. By the time your big day Cheap Thrills ................................................ Sia & Sean Paul arrives, we will completely -

Narratives of Two Mothers on Raising Their Children with Disabilities

University of Northern Iowa UNI ScholarWorks Dissertations and Theses @ UNI Student Work 2016 "Joy for what it is": Narratives of two mothers on raising their children with disabilities Zeina H. Yousof University of Northern Iowa Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy Copyright ©2016 Zeina H. Yousof Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uni.edu/etd Part of the Special Education and Teaching Commons Recommended Citation Yousof, Zeina H., ""Joy for what it is": Narratives of two mothers on raising their children with disabilities" (2016). Dissertations and Theses @ UNI. 345. https://scholarworks.uni.edu/etd/345 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Work at UNI ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses @ UNI by an authorized administrator of UNI ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Copyright by ZEINA H. YOUSOF 2016 All Rights Reserved “JOY FOR WHAT IS”: NARRATIVES OF TWO MOTHERS ON RAISING THEIR CHILDREN WITH DISABILITIES An Abstract of a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Education Approved: ________________________________ Dr. Amy J. Petersen, Committee Chair ________________________________ Dr. Kavita Dhanwada, Dean of the Graduate College Zeina H. Yousof University of Northern Iowa December 2016 ABSTRACT The purpose of this study was to explore the experiences of two mothers of children with disabilities on parenting their children and navigating the world of disabilities. For many parents, the diagnosis of a child with disabilities represents a form of interpersonal loss through the loss of the imagined child. -

This Cannot Happen Here Studies of the Niod Institute for War, Holocaust and Genocide Studies

This Cannot Happen Here studies of the niod institute for war, holocaust and genocide studies This niod series covers peer reviewed studies on war, holocaust and genocide in twentieth century societies, covering a broad range of historical approaches including social, economic, political, diplomatic, intellectual and cultural, and focusing on war, mass violence, anti- Semitism, fascism, colonialism, racism, transitional regimes and the legacy and memory of war and crises. board of editors: Madelon de Keizer Conny Kristel Peter Romijn i Ralf Futselaar — Lard, Lice and Longevity. The standard of living in occupied Denmark and the Netherlands 1940-1945 isbn 978 90 5260 253 0 2 Martijn Eickhoff (translated by Peter Mason) — In the Name of Science? P.J.W. Debye and his career in Nazi Germany isbn 978 90 5260 327 8 3 Johan den Hertog & Samuël Kruizinga (eds.) — Caught in the Middle. Neutrals, neutrality, and the First World War isbn 978 90 5260 370 4 4 Jolande Withuis, Annet Mooij (eds.) — The Politics of War Trauma. The aftermath of World War ii in eleven European countries isbn 978 90 5260 371 1 5 Peter Romijn, Giles Scott-Smith, Joes Segal (eds.) — Divided Dreamworlds? The Cultural Cold War in East and West isbn 978 90 8964 436 7 6 Ben Braber — This Cannot Happen Here. Integration and Jewish Resistance in the Netherlands, 1940-1945 isbn 978 90 8964 483 8 This Cannot Happen Here Integration and Jewish Resistance in the Netherlands, 1940-1945 Ben Braber Amsterdam University Press 2013 This book is published in print and online through the online oapen library (www.oapen.org) oapen (Open Access Publishing in European Networks) is a collaborative initiative to develop and implement a sustainable Open Access publication model for academic books in the Humanities and Social Sciences. -

Onderzoek Warmtetransitie De Ronde Venen Afwegingskader

Onderzoek warmtetransitie De Ronde Venen Afwegingskader Onderzoek warmtetransitie De Ronde Venen Afwegingskader Dit rapport is geschreven door: Emma Koster, Fenneke van de Poll, Hein-Bert Schurink, Marianne Teng Delft, CE Delft, juni 2020 Publicatienummer: 20.190458.083 Gemeenten / Beleid / Wijken / Energievoorziening / Duurzaam / Warmte / Elektriciteit/ Technologie / Economische factoren Opdrachtgever: Gemeente Ronde Venen Alle openbare publicaties van CE Delft zijn verkrijgbaar via www.ce.nl Meer informatie over de studie is te verkrijgen bij de projectleider Emma Koster (CE Delft) © copyright, CE Delft, Delft CE Delft Committed to the Environment CE Delft draagt met onafhankelijk onderzoek en advies bij aan een duurzame samenleving. Wij zijn toon- aangevend op het gebied van energie, transport en grondstoffen. Met onze kennis van techniek, beleid en economie helpen we overheden, NGO’s en bedrijven structurele veranderingen te realiseren. Al 40 jaar werken betrokken en kundige medewerkers bij CE Delft om dit waar te maken. 1 190458 - Onderzoek warmtetransitie De Ronde Venen – Juni 2020 Inhoud 1 Inleiding 4 1.1 Doel van het onderzoek 4 1.2 Opbouw van dit afwegingskader 4 1.3 Gebiedsindeling 5 2 Kostenberekeningen: methodiek en aannames 6 2.1 Beschikbare warmtebronnen 7 2.2 Nationale kosten 9 2.3 Eindgebruikerskosten 10 2.4 Conclusie 12 3 Ruimtebeslag 13 3.1 Ruimtebeslag in de woning 13 3.2 Elektriciteitsproductie 13 3.3 Groengasproductie 15 3.4 Conclusie 16 4 Duurzaamheidsbijdrage 18 5 Kansenkaarten 21 5.1 Methodiek 21 5.2 Resultaten -

A Critical Grounded Theory of the Development of Student Leaders with Historically Marginalized Identities

“Everything I Did Was Black. That’s What I Was There For.”: A Critical Grounded Theory of the Development of Student Leaders with Historically Marginalized Identities Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Womble, Allen A. Citation Womble, Allen A. (2021). “Everything I Did Was Black. That’s What I Was There For.”: A Critical Grounded Theory of the Development of Student Leaders with Historically Marginalized Identities (Doctoral dissertation, University of Arizona, Tucson, USA). Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction, presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 26/09/2021 11:58:53 Item License http://rightsstatements.org/vocab/InC/1.0/ Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/660217 “EVERYTHING I DID WAS BLACK. THAT’S WHAT I WAS THERE FOR.”: A CRITICAL GROUNDED THEORY OF THE DEVELOPMENT OF STUDENT LEADERS WITH HISTORICALLY MARGINALIZED IDENTITIES by Allen A. Womble __________________________________ Copyright © Allen A. Womble 2021 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATIONAL POLICY STUDIES AND PRACTICE In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2021 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Dissertation Committee, we certify that we have read the dissertation prepared by: Allen Alfred Womble titled: “EVERYTHING I DID WAS BLACK. THAT’S WHAT I WAS THERE FOR.”: and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy. -

Band Song-List

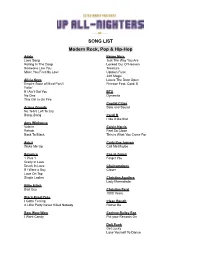

SONG LIST Modern Rock, Pop & Hip-Hop Adele Bruno Mars Love Song Just The Way You Are Rolling In The Deep Locked Out Of Heaven Someone Like You Treasure Make You Feel My Love Uptown Funk 24K Magic Alicia Keys Leave The Door Open Empire State of Mind Part II Finesse Feat. Cardi B Fallin' If I Ain't Got You BTS No One Dynamite This Girl Is On Fire Capital Cities Ariana Grande Safe and Sound No Tears Left To Cry Bang, Bang Cardi B I like it like that Amy Winhouse Valerie Calvin Harris Rehab Feel So Close Back To Black This is What You Came For Avicii Carly Rae Jepsen Wake Me Up Call Me Maybe Beyonce Cee-lo Green 1 Plus 1 Forget You Crazy In Love Drunk In Love Chainsmokers If I Were a Boy Closer Love On Top Single Ladies Christina Aguilera Lady Marmalade Billie Eilish Bad Guy Christina Perri 1000 Years Black-Eyed Peas I Gotta Feeling Clean Bandit A Little Party Never Killed Nobody Rather Be Bow Wow Wow Corinne Bailey Rae I Want Candy Put your Records On Daft Punk Get Lucky Lose Yourself To Dance Justin Timberlake Darius Rucker Suit & Tie Wagon Wheel Can’t Stop The Feeling Cry Me A River David Guetta Love You Like I Love You Titanium Feat. Sia Sexy Back Drake Jay-Z and Alicia Keys Hotline Bling Empire State of Mind One Dance In My Feelings Jess Glynne Hold One We’re Going Home Hold My Hand Too Good Controlla Jessie J Bang, Bang DNCE Domino Cake By The Ocean Kygo Disclosure Higher Love Latch Katy Perry Dua Lipa Chained To the Rhythm Don’t Start Now California Gurls Levitating Firework Teenage Dream Duffy Mercy Lady Gaga Bad Romance Ed Sheeran Just Dance Shape Of You Poker Face Thinking Out loud Perfect Duet Feat. -

A Rapid Biological Assessment of the Upper Palumeu River Watershed (Grensgebergte and Kasikasima) of Southeastern Suriname

Rapid Assessment Program A Rapid Biological Assessment of the Upper Palumeu River Watershed (Grensgebergte and Kasikasima) of Southeastern Suriname Editors: Leeanne E. Alonso and Trond H. Larsen 67 CONSERVATION INTERNATIONAL - SURINAME CONSERVATION INTERNATIONAL GLOBAL WILDLIFE CONSERVATION ANTON DE KOM UNIVERSITY OF SURINAME THE SURINAME FOREST SERVICE (LBB) NATURE CONSERVATION DIVISION (NB) FOUNDATION FOR FOREST MANAGEMENT AND PRODUCTION CONTROL (SBB) SURINAME CONSERVATION FOUNDATION THE HARBERS FAMILY FOUNDATION Rapid Assessment Program A Rapid Biological Assessment of the Upper Palumeu River Watershed RAP (Grensgebergte and Kasikasima) of Southeastern Suriname Bulletin of Biological Assessment 67 Editors: Leeanne E. Alonso and Trond H. Larsen CONSERVATION INTERNATIONAL - SURINAME CONSERVATION INTERNATIONAL GLOBAL WILDLIFE CONSERVATION ANTON DE KOM UNIVERSITY OF SURINAME THE SURINAME FOREST SERVICE (LBB) NATURE CONSERVATION DIVISION (NB) FOUNDATION FOR FOREST MANAGEMENT AND PRODUCTION CONTROL (SBB) SURINAME CONSERVATION FOUNDATION THE HARBERS FAMILY FOUNDATION The RAP Bulletin of Biological Assessment is published by: Conservation International 2011 Crystal Drive, Suite 500 Arlington, VA USA 22202 Tel : +1 703-341-2400 www.conservation.org Cover photos: The RAP team surveyed the Grensgebergte Mountains and Upper Palumeu Watershed, as well as the Middle Palumeu River and Kasikasima Mountains visible here. Freshwater resources originating here are vital for all of Suriname. (T. Larsen) Glass frogs (Hyalinobatrachium cf. taylori) lay their -

Eric P. Rudge Ll.M

ERIC P. RUDGE LL.M. & LL.M. Kromanti Kodjostraat hoek Aboenawrokostraat nr. 19A, Geyersvlijt Paramaribo – Suriname S.A. Tel + app: (00597) 8835621 (mobile) Private: 00597) 455363 App nr.: (005999) 6635527 E-mail: [email protected] -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Name: RUDGE First and middle name: ERIC PATRICK Date of birth: NOVEMBER 16, 1960 Place of birth: PARAMARIBO, SURINAME Religion: ROMAN CATHOLIC Domicile: SURINAME Address: KROMANTI KODJO HK ABOENAWOKOSTRAAT nr. 19A Nationality: SURINAMESE Children: 4 (FOUR) Marital status: SEPARATED 1 EDUCATION: # Legal 2018 – April 2019 Specialized courses tailored for the members of the Judiciary in Suriname initiated by the High Court of Justice in Suriname, offered through de ‘Stichting Juridische Samenwerking Suriname Nederland’ in cooperation with ‘Studiecentrum Rechtspleging’ (SSR), Zutphen, The Netherlands July 2010 External Action and Representation of the European Union: Implementing the Lisbon Treaty, CLEER (Centre for the Law of EU External Relations) and T.M.C. Asser Institute Inter-University Research Centre, Brussels, Belgium March 2008 The Movement of Persons and Goods in the Caribbean Area, 35th External Programme, The Hague Academy of International Law in cooperation with the Government of the Dominican Republic, Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic September 2007 30th Sanremo Roundtable on Current Issues of International Humanitarian Law, International Institute of Humanitarian Law (IIHL), International -

Defense Generated Impasse: the Patient's Experience of the Analyst's

Defense Generated Impasse: The Patient’s Experience of the Analyst’s Defensiveness1 Cheryl Chenot, Psy.D., MFT Institute of Contemporary Psychoanalysis Los Angeles, California 2000, 2012 ∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞ Any or all of this document may not be reproduced without the consent of the author. 1 This paper is about healthy and dysfunctional conversation. This paper emerged thanks to rich conversations with people who contributed thoughts and perceptions, and who helped me to clarify my ideas over the four year evolution of this paper. Their voices are to be found throughout the paper. Many thanks to Gary Sattler, Lolita Sapriel and William Coburn for their conceptual contributions, and to Elizabeth Altman and Carol Fahy for their thoughtful suggestions about form and structure. I also wish to express my gratitude to the many people who encouraged me in diverse ways, who are too numerous to mention in an exhaustive list, and too important to risk omitting accidentally from such a list. Special gratitude goes to Lynne Jacobs, who has a unique gift for cultivating my embryonic thoughts, for her generosity with her time. While their contributions have been invaluable, I am solely responsible for the contents of this paper. Introduction When .... therapist's and patient's primary vulnerabilities have been activated and intersect problematically, patient and therapist have become entangled in a relational knot to which both have contributed and from which they cannot extricate themselves. Like a Chinese puzzle, the knot becomes tighter the harder they try to loosen it. They each become dangerous to the other and increasingly defensive. Their perspectives on what is occurring differ and collide.