A Critical Grounded Theory of the Development of Student Leaders with Historically Marginalized Identities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Just the Right Song at Just the Right Time Music Ideas for Your Celebration Chart Toppin

JUST THE RIGHT SONG AT CHART TOPPIN‟ 1, 2 Step ....................................................................... Ciara JUST THE RIGHT TIME 24K Magic ........................................................... Bruno Mars You know that the music at your party will have a Baby ................................................................ Justin Bieber tremendous impact on the success of your event. We Bad Romance ..................................................... Lady Gaga know that it is so much more than just playing the Bang Bang ............................................................... Jessie J right songs. It‟s playing the right songs at the right Blurred Lines .................................................... Robin Thicke time. That skill will take a party from good to great Break Your Heart .................................. Taio Cruz & Ludacris every single time. That‟s what we want for you and Cake By The Ocean ................................................... DNCE California Girls ..................................................... Katie Perry your once in a lifetime celebration. Call Me Maybe .......................................... Carly Rae Jepson Can‟t Feel My Face .......................................... The Weeknd We succeed in this by taking the time to get to know Can‟t Stop The Feeling! ............................. Justin Timberlake you and your musical tastes. By the time your big day Cheap Thrills ................................................ Sia & Sean Paul arrives, we will completely -

Narratives of Two Mothers on Raising Their Children with Disabilities

University of Northern Iowa UNI ScholarWorks Dissertations and Theses @ UNI Student Work 2016 "Joy for what it is": Narratives of two mothers on raising their children with disabilities Zeina H. Yousof University of Northern Iowa Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy Copyright ©2016 Zeina H. Yousof Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uni.edu/etd Part of the Special Education and Teaching Commons Recommended Citation Yousof, Zeina H., ""Joy for what it is": Narratives of two mothers on raising their children with disabilities" (2016). Dissertations and Theses @ UNI. 345. https://scholarworks.uni.edu/etd/345 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Work at UNI ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses @ UNI by an authorized administrator of UNI ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Copyright by ZEINA H. YOUSOF 2016 All Rights Reserved “JOY FOR WHAT IS”: NARRATIVES OF TWO MOTHERS ON RAISING THEIR CHILDREN WITH DISABILITIES An Abstract of a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Education Approved: ________________________________ Dr. Amy J. Petersen, Committee Chair ________________________________ Dr. Kavita Dhanwada, Dean of the Graduate College Zeina H. Yousof University of Northern Iowa December 2016 ABSTRACT The purpose of this study was to explore the experiences of two mothers of children with disabilities on parenting their children and navigating the world of disabilities. For many parents, the diagnosis of a child with disabilities represents a form of interpersonal loss through the loss of the imagined child. -

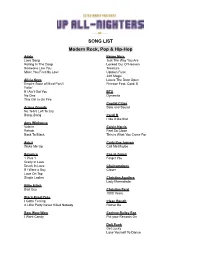

Band Song-List

SONG LIST Modern Rock, Pop & Hip-Hop Adele Bruno Mars Love Song Just The Way You Are Rolling In The Deep Locked Out Of Heaven Someone Like You Treasure Make You Feel My Love Uptown Funk 24K Magic Alicia Keys Leave The Door Open Empire State of Mind Part II Finesse Feat. Cardi B Fallin' If I Ain't Got You BTS No One Dynamite This Girl Is On Fire Capital Cities Ariana Grande Safe and Sound No Tears Left To Cry Bang, Bang Cardi B I like it like that Amy Winhouse Valerie Calvin Harris Rehab Feel So Close Back To Black This is What You Came For Avicii Carly Rae Jepsen Wake Me Up Call Me Maybe Beyonce Cee-lo Green 1 Plus 1 Forget You Crazy In Love Drunk In Love Chainsmokers If I Were a Boy Closer Love On Top Single Ladies Christina Aguilera Lady Marmalade Billie Eilish Bad Guy Christina Perri 1000 Years Black-Eyed Peas I Gotta Feeling Clean Bandit A Little Party Never Killed Nobody Rather Be Bow Wow Wow Corinne Bailey Rae I Want Candy Put your Records On Daft Punk Get Lucky Lose Yourself To Dance Justin Timberlake Darius Rucker Suit & Tie Wagon Wheel Can’t Stop The Feeling Cry Me A River David Guetta Love You Like I Love You Titanium Feat. Sia Sexy Back Drake Jay-Z and Alicia Keys Hotline Bling Empire State of Mind One Dance In My Feelings Jess Glynne Hold One We’re Going Home Hold My Hand Too Good Controlla Jessie J Bang, Bang DNCE Domino Cake By The Ocean Kygo Disclosure Higher Love Latch Katy Perry Dua Lipa Chained To the Rhythm Don’t Start Now California Gurls Levitating Firework Teenage Dream Duffy Mercy Lady Gaga Bad Romance Ed Sheeran Just Dance Shape Of You Poker Face Thinking Out loud Perfect Duet Feat. -

Defense Generated Impasse: the Patient's Experience of the Analyst's

Defense Generated Impasse: The Patient’s Experience of the Analyst’s Defensiveness1 Cheryl Chenot, Psy.D., MFT Institute of Contemporary Psychoanalysis Los Angeles, California 2000, 2012 ∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞ Any or all of this document may not be reproduced without the consent of the author. 1 This paper is about healthy and dysfunctional conversation. This paper emerged thanks to rich conversations with people who contributed thoughts and perceptions, and who helped me to clarify my ideas over the four year evolution of this paper. Their voices are to be found throughout the paper. Many thanks to Gary Sattler, Lolita Sapriel and William Coburn for their conceptual contributions, and to Elizabeth Altman and Carol Fahy for their thoughtful suggestions about form and structure. I also wish to express my gratitude to the many people who encouraged me in diverse ways, who are too numerous to mention in an exhaustive list, and too important to risk omitting accidentally from such a list. Special gratitude goes to Lynne Jacobs, who has a unique gift for cultivating my embryonic thoughts, for her generosity with her time. While their contributions have been invaluable, I am solely responsible for the contents of this paper. Introduction When .... therapist's and patient's primary vulnerabilities have been activated and intersect problematically, patient and therapist have become entangled in a relational knot to which both have contributed and from which they cannot extricate themselves. Like a Chinese puzzle, the knot becomes tighter the harder they try to loosen it. They each become dangerous to the other and increasingly defensive. Their perspectives on what is occurring differ and collide. -

Songs by Title

16,341 (11-2020) (Title-Artist) Songs by Title 16,341 (11-2020) (Title-Artist) Title Artist Title Artist (I Wanna Be) Your Adams, Bryan (Medley) Little Ole Cuddy, Shawn Underwear Wine Drinker Me & (Medley) 70's Estefan, Gloria Welcome Home & 'Moment' (Part 3) Walk Right Back (Medley) Abba 2017 De Toppers, The (Medley) Maggie May Stewart, Rod (Medley) Are You Jackson, Alan & Hot Legs & Da Ya Washed In The Blood Think I'm Sexy & I'll Fly Away (Medley) Pure Love De Toppers, The (Medley) Beatles Darin, Bobby (Medley) Queen (Part De Toppers, The (Live Remix) 2) (Medley) Bohemian Queen (Medley) Rhythm Is Estefan, Gloria & Rhapsody & Killer Gonna Get You & 1- Miami Sound Queen & The March 2-3 Machine Of The Black Queen (Medley) Rick Astley De Toppers, The (Live) (Medley) Secrets Mud (Medley) Burning Survivor That You Keep & Cat Heart & Eye Of The Crept In & Tiger Feet Tiger (Down 3 (Medley) Stand By Wynette, Tammy Semitones) Your Man & D-I-V-O- (Medley) Charley English, Michael R-C-E Pride (Medley) Stars Stars On 45 (Medley) Elton John De Toppers, The Sisters (Andrews (Medley) Full Monty (Duets) Williams, Sisters) Robbie & Tom Jones (Medley) Tainted Pussycat Dolls (Medley) Generation Dalida Love + Where Did 78 (French) Our Love Go (Medley) George De Toppers, The (Medley) Teddy Bear Richard, Cliff Michael, Wham (Live) & Too Much (Medley) Give Me Benson, George (Medley) Trini Lopez De Toppers, The The Night & Never (Live) Give Up On A Good (Medley) We Love De Toppers, The Thing The 90 S (Medley) Gold & Only Spandau Ballet (Medley) Y.M.C.A. -

Cardib “I Like It” Sample of Lyrics: Drake “In My Feelings” Sample of Lyrics: TOP SONG LYRICS THROUGH the DECADES

TOP SONG LYRICS THROUGH THE DECADES 2018 CardiB “I like it” sample of lyrics: I Like It lyrics © Warner/Chappell Music, Inc, BMG Rights Management, Kobalt Music Publishing Ltd., Sony/ATV Music Publishing LLC, Universal Music Publishing Group Now I like dollars, I like diamonds I like stunting, I like shining I like million dollar deals where’s my pen? B***h I'm signin' I like those Balenciagas, the ones that look like socks I like going to the jeweler, I put rocks all in my watch I like texts from my exes when they want a second chance I like proving n****s wrong, I do what they say I can't Flexing on b*****s as hard as I can Eating halal, driving the Lam' Told that b***h I'm sorry though 'Bout my coins like Mario (Mario) Yeah they call me Cardi B, I run this s**t like cardio Oh, facts Drake “in my feelings” sample of lyrics: In My Feelings lyrics © Warner/Chappell Music, Inc, Peermusic Publishing, Reservoir Media Management Inc, Kobalt Music Publishing Ltd. Kiki, do you love me? Are you riding? Say you'll never ever leave from beside me Cause I want ya, and I need ya And when you get to toppin', I see that you've been learnin' And when I take you shoppin' you spend it like you earned it And when you popped off on your ex he deserved it I show him how the neck work F**k that Netflix and chill, what's your net-net-net worth? 'Cause I want ya, and I need ya From beside me, 'cause I want ya, and I Bring that a**, bring that a**, bring that a** back B-bring that a**, bring that a**, bring that a** back Shawty say the n***a that she with can't hit But shawty, I'ma hit it, hit it like I can't miss TOP SONG LYRICS THROUGH THE DECADES 2008 Flo rida “Low” sample of lyrics: Low (feat. -

Most Requested Songs of 2020

Top 200 Most Requested Songs Based on millions of requests made through the DJ Intelligence music request system at weddings & parties in 2020 RANK ARTIST SONG 1 Whitney Houston I Wanna Dance With Somebody (Who Loves Me) 2 Mark Ronson Feat. Bruno Mars Uptown Funk 3 Cupid Cupid Shuffle 4 Journey Don't Stop Believin' 5 Neil Diamond Sweet Caroline (Good Times Never Seemed So Good) 6 Usher Feat. Ludacris & Lil' Jon Yeah 7 Walk The Moon Shut Up And Dance 8 V.I.C. Wobble 9 Earth, Wind & Fire September 10 Justin Timberlake Can't Stop The Feeling! 11 Garth Brooks Friends In Low Places 12 DJ Casper Cha Cha Slide 13 ABBA Dancing Queen 14 Bruno Mars 24k Magic 15 Outkast Hey Ya! 16 Black Eyed Peas I Gotta Feeling 17 Kenny Loggins Footloose 18 Bon Jovi Livin' On A Prayer 19 AC/DC You Shook Me All Night Long 20 Spice Girls Wannabe 21 Chris Stapleton Tennessee Whiskey 22 Backstreet Boys Everybody (Backstreet's Back) 23 Bruno Mars Marry You 24 Miley Cyrus Party In The U.S.A. 25 Van Morrison Brown Eyed Girl 26 B-52's Love Shack 27 Killers Mr. Brightside 28 Def Leppard Pour Some Sugar On Me 29 Dan + Shay Speechless 30 Flo Rida Feat. T-Pain Low 31 Sir Mix-A-Lot Baby Got Back 32 Montell Jordan This Is How We Do It 33 Isley Brothers Shout 34 Ed Sheeran Thinking Out Loud 35 Luke Combs Beautiful Crazy 36 Ed Sheeran Perfect 37 Nelly Hot In Herre 38 Marvin Gaye & Tammi Terrell Ain't No Mountain High Enough 39 Taylor Swift Shake It Off 40 'N Sync Bye Bye Bye 41 Lil Nas X Feat. -

Axis-Parents-Guide-To-Drake.Pdf

Drake “Drake is an interpreter, in other words, of the people he is trying to reach—an artist who can write lyrics that wide swaths of listeners will want to take ownership of and hooks that we will all want to sing to ourselves as we walk down the street. —Leon Neyfakh, “Peak Drake,” The FADER Does Drake have you in your feelings about how much your kids are listening to him? John Lennon famously said the Beatles were bigger than Jesus, but Aubrey Graham, aka Drake aka Drizzy, is now the best-selling solo male artist of all time. He has surpassed Elvis and Eminem, with over $218,000,000 in total record sales. Not only that, he was Billboard’s 2018 Top Artist and Spotify’s most-streamed artist, track, and album of 2018. Described by one writer as having “the Midas touch when it comes to making hits and singles,” it seems as though everything Drake does is successful. He appeals to those who like “harder” rap, but still excites a One Direction level of infatuation in young girls. Other rappers can take shots at his son and his parents [warning: strong language] without doing real damage to his career. He’s able to transform up-and-coming artists into superstars just by featuring them on his albums or being featured on theirs. With all of his influence on both his fans and the culture at large, it’s important to understand who Drake is, what he stands for, and what he’s teaching, both explicitly and implicitly, the people who listen to him. -

Marvin Gaye & Tammi Terrell Aint Too Proud To

Ain't Nothing Like The Real Thing -Marvin Gaye & Tammi Terrell Aint Too Proud To Beg -The Temptations All About That Bass – Meghan Trainor At Last - Etta James Bang Bang – Nicki Minaj Billie Jean – Michael Jackson Blame It On The Alcohol – Jamie Foxx Blank Space – Taylor Swift Blurred Lines – Robin Thicke Boo'd Up - Ella Mai Boogie Man- KC & The Sunshine Band Boogie Oogie Oogie - Taste Of Honey Boom Shake The Room – DJ Jazzy Jeff & The Fresh Prince Brick House -The Commodores Bust A Move – Young MC Can’t Feel My face – The Weekend Can't Get Next To You -The Temptations Can't Help Falling In Love - UB40 Can’t Keep My Hands To Myself – Selena Gomez Can’t Stop The Feelin – Justin Timberlake Can't Take My Eyes Off Of You -Frankie Valley & 4 Seasons Chain Of Fools -Aretha Franklin Chandelier – Sia Closer - Chainsmokers Come Away with me - Norah Jones Confident – Demi Lovato Crazy – Gnarls Barkley Crazy In Love – Beyonce Da Butt – E.W. Dance To The Music -Sly & The Family Stone Dancing In The Street -Martha Reeves & The Vandellas Dangerously In Love – Beyonce Déjà vu – Beyonce DJ Got Us Fallin In Love – Usher Doo Wop – Lauryn Hill Don’t Stop ‘Till You Get Enough – Michael Jackson Don’t Stop Believin’ -- Journey Don't Know Why - Norah Jones Drunk In Love - Beyonc ft Jay Z Dynomite – Taio Cruz Everybody Dance Now – C&C And Music Factory Everybody Dance Now C & C -Dance Factory Everyday People -Sly & The Family Stone Feel Like A Woman – Shania Twain Finesse – Bruno Mars Firework – Katy Perry Fancy – Iggy Azalea Forget You – Cee Lo Green Fresh Prince Of Bel-Air – Will Smith Funky Broadway -Wilson Picket Get Down Tonight -K.C. -

Copyright Notices, July 2018

Copyright Lore Top Summer Hits ALISON HALL For many of us, a song can magically transport us back in time. Summer songs seem to be even more powerful. Looking back at sixty years of the Billboard Hot 100 lists, here’s a sampling of number-one summer flashback hits in ten-year increments. All songs mentioned are registered with the Copyright Office as words and music, sound recordings, or both. (For the purpose of this article, “summer” includes all of June, July, and August.) Burt Bacharach and Hal David followed 1958 and held the top spot for much of the summer until instrumental “Grazing In The Billboard started the Hot 100 chart on Grass” recorded by Hugh Masekela and August 4, 1958, so that summer’s top hits written by Philemon Hou took over. “Hello, only include those in the month of August. I Love You” recorded by The Doors and Ricky Nelson’s recording of “Poor Little written by front man Jim Morrison took Fool,” written by Shari Sheeley, kicked off over the top spot for a week, and then the the list at number one. “Nel Blu Dipinto summer finished with “People Got To Be Di Blu (Volaré)” followed at number one, Free” recorded by The Rascals and written performed by Domenico Modugno and by band members Felix Cavaliere and written by Modugno with Franco Migliacci. Eddie Brigati topping the charts. Doo-wop vocal group The Elegants closed Ricky Nelson scored the first number one hit on Billboard’s Hot 100 chart with “Poor Little out the month with their number one hit Fool” from his self-titled album in the summer “Little Star,” written by group members 1978 of 1958. -

Sample Song List 032419

Song Name Artist Category (If You're Wondering If I Want You To) I Want You To Weezer 00's Hip Hop, Pop, Rock 1, 2, 3, 4 Plain White T's 00's Hip Hop, Pop, Rock 1,2 Step Ciara f/Missy ELLiott 00's Hip Hop, Pop, Rock 7 Things MiLey Cyrus 00's Hip Hop, Pop, Rock 867-5309 / Jenny Tommy Tutone 00's Hip Hop, Pop, Rock A Love That WiLL Last Renee OLstead 00's Hip Hop, Pop, Rock A Moment Like This KeLLy CLarkson 00's Hip Hop, Pop, Rock A Sky FuLL of Stars CoLdpLay 00's Hip Hop, Pop, Rock A Thousand MiLes Vanessa CarLton 00's Hip Hop, Pop, Rock Alejandro Lady GaGa f/ Redone 00's Hip Hop, Pop, Rock AlL About That Bass Meghan Trainor 00's Hip Hop, Pop, Rock AlL Summer Long (Summertime) Kid Rock 00's Hip Hop, Pop, Rock American Boy (Radio Edit w/ Kanye) EsteLLe 00's Hip Hop, Pop, Rock Anaconda Nicki Minaj 00's Hip Hop, Pop, Rock Apache (Jump On It) The SugarhiLL Gang 00's Hip Hop, Pop, Rock ApoLogize TimbaLand f/ One RepubLic 00's Hip Hop, Pop, Rock Are You Gonna Go My Way Lenny Kravitz 00's Hip Hop, Pop, Rock At Last Beyoncé 00's Hip Hop, Pop, Rock Baby Got Back (Big Butt Song) Sir Mix-a-Lot 00's Hip Hop, Pop, Rock Bad Boy for Life P. Diddy, BLack Rob & Mark Curry 00's Hip Hop, Pop, Rock Bad Romance Lady Gaga 00's Hip Hop, Pop, Rock Bang Bang Jessie J, Ariana Grande & Nicki Minaj 00's Hip Hop, Pop, Rock Beat It FaLL Out Boy f/ John Mayer 00's Hip Hop, Pop, Rock Because You Live Jesse McCartney 00's Hip Hop, Pop, Rock Beep Pussycat DoLLs, The 00's Hip Hop, Pop, Rock Beer ReeL Big Fish 00's Hip Hop, Pop, Rock Berzerk Eminem 00's Hip Hop, Pop, Rock Best Friend (feat. -

The Mix Song List

THE MIX SONG LIST CONTEMPORARY 2010’s CENTURIES/ fall out boy 24K MAGIC/ bruno mars CHAINED TO THE RHYTHM/ katy perry ADDICTED TO A MEMORY/ zedd CHANDELIER/ sia ADVENTURE OF A LIFETIME/ coldplay CHEAP THRILLS/ sia & sean paul AFTERGLOW/ ed sheeran CHEERLEADER/ omi AIN’T IT FUN/ paramore CIRCLES/ post malone AIRPLANES/ b.o.b w/haley williams CLASSIC/ mkto ALIVE/ krewella CLOSER/ chainsmokers ALL ABOUT THAT BASS/ meghan trainor CLUB CAN’T HANDLE ME/ flo rida ALL ABOUT THAT BASS/ postmodern jukebox COME GET IT BAE/ pharrell williams ALL I NEED/ awol nation COOLER THAN ME/ mike posner ALL I ASK/ adele COOL KIDS/ echosmith ALL OF ME/ john legend COUNTING STARS/ one republic ALL THE WAY/ timeflies CRAZY/ kat dahlia ALWAYS REMEMBER US THIS WAY/ lady gaga CRUISE REMIX/ florida georgia line & nelly A MILLION DREAMS/ greatest showman DANGEROUS/ guetta & martin AM I WRONG/ nico & vinz DAYLIGHT/ maroon 5 ANIMALS/ maroon 5 DEAR FUTURE HUSBAND/ meghan trainor ANYONE/ justin bieber DELICATE/ taylor swift APPLAUSE/ lady gaga DIAMONDS/ sam smith A THOUSAND YEARS/ christina perri DIE WITH YOU/ beyonce BABY/ justin bieber DIE YOUNG/ kesha BAD BLOOD/ taylor swift DOMINO/ jessie j BAD GUY/ billie eilish DON’T LET ME DOWN/ chainsmokers BANG BANG/ jessie j and ariana grande DON’T START NOW/ dua lipa BEFORE I LET GO/ beyonce DON’T STOP THE PARTY/ pitbull BENEATH YOUR BEAUTIFUL/ labrinth DRINK YOU AWAY/ justin timberlake BEAUTIFUL PEOPLE/ chris brown DRIVE BY/ train BEST DAY OF MY LIFE/ american authors DRIVERS LICENSE/ olivia rodrigo BEST SONG EVER/ one direction