Circuit Breakers, Volatility, and the US Equity Markets

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Did Spillovers from Europe Indeed Contribute to the 2010 U.S. Flash Crash?

No. 622 / January 2019 Did Spillovers From Europe Indeed Contribute to the 2010 U.S. Flash Crash? David-Jan Jansen Did Spillovers From Europe Indeed Contribute to the 2010 U.S. Flash Crash? David-Jan Jansen * * Views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect official positions of De Nederlandsche Bank. De Nederlandsche Bank NV Working Paper No. 622 P.O. Box 98 1000 AB AMSTERDAM January 2019 The Netherlands Did Spillovers From Europe Indeed Contribute to the 2010 U.S. Flash Crash?* David-Jan Jansen a a De Nederlandsche Bank, Amsterdam, The Netherlands This version: January 2019 Abstract Using intraday data, we study spillovers from European stock markets to the U.S. in the hours before the flash crash on 6 May 2010. Many commentators have pointed to negative market sentiment and high volatility during the European trading session before the Flash Crash. However, based on a range of vector autoregressive models, we find no robust evidence that spillovers increased at that time. On the contrary, spillovers on 6 May were mostly smaller than in the preceding days, during which there was great uncertainty surrounding the Greek sovereign debt crisis. The absence of evidence for spillovers underscores the difficulties in understanding the nature of flash events in financial markets. Keywords: flash crash, spillovers, financial stability, connectedness. JEL classifications: G15, N22, N24. * This paper benefitted from discussions with Sweder van Wijnbergen as well as from research assistance by Jack Bekooij. Any errors and omissions remain my responsibility. Views expressed in the paper do not necessarily coincide with those of de Nederlandsche Bank or the Eurosystem. -

Cracks in the Pipeline 2

MEDIA CONTACT: Lauren Strayer | [email protected] 212-389-1413 FINANCIAL PIPELINE .o rg Series CRACKS IN THE PIPELINE 2 HIGH FREQUENCY TRADING by: Wallace C. Turbeville his is the second of a series of articles, that increase the inefficiency of Capital Intermediation and entitled “The Financial Pipeline Series”, its cost. The increased volumes in the traded markets are examining the underlying validity of the largely a result of high-speed, computer driven trading assertion that regulation of the financial by large banks and smaller specialized firms. This article markets reduces their efficiency. These illustrates how this type of trading (along with other activ- articles assert that the value of the finan- ities discussed in subsequent articles) extracts value from cial markets is often mis-measured. The the Capital Intermediation process rendering it less efficient. efficiency of the market in intermediat- It also describes how the value extracted is a driver of even ing flows between capital investors and more increased volume creating a dangerous and powerful capital users (like manufacturing and service businesses, feedback loop. individuals and governments) is the proper measure. Unreg- Tying increased trading volume to inefficiencies runs ulated markets are found to be chronically inefficient using counter to a fundamental tenet of industry opponents to Tthis standard. This costs the economy enormous amounts financial reform. They assert that burdens on trading will each year. In addition, the inefficiencies create stresses to the reduce volumes and thereby impair the efficient functioning system that make systemic crises inevitable. Only prudent of the markets. regulation that moderates trading behavior can reduce these The industry’s position that increased volume reduces inefficiencies. -

The Future of Computer Trading in Financial Markets an International Perspective

The Future of Computer Trading in Financial Markets An International Perspective FINAL PROJECT REPORT This Report should be cited as: Foresight: The Future of Computer Trading in Financial Markets (2012) Final Project Report The Government Office for Science, London The Future of Computer Trading in Financial Markets An International Perspective This Report is intended for: Policy makers, legislators, regulators and a wide range of professionals and researchers whose interest relate to computer trading within financial markets. This Report focuses on computer trading from an international perspective, and is not limited to one particular market. Foreword Well functioning financial markets are vital for everyone. They support businesses and growth across the world. They provide important services for investors, from large pension funds to the smallest investors. And they can even affect the long-term security of entire countries. Financial markets are evolving ever faster through interacting forces such as globalisation, changes in geopolitics, competition, evolving regulation and demographic shifts. However, the development of new technology is arguably driving the fastest changes. Technological developments are undoubtedly fuelling many new products and services, and are contributing to the dynamism of financial markets. In particular, high frequency computer-based trading (HFT) has grown in recent years to represent about 30% of equity trading in the UK and possible over 60% in the USA. HFT has many proponents. Its roll-out is contributing to fundamental shifts in market structures being seen across the world and, in turn, these are significantly affecting the fortunes of many market participants. But the relentless rise of HFT and algorithmic trading (AT) has also attracted considerable controversy and opposition. -

Ai: Understanding and Harnessing the Potential Wireless & Digital Services Ai: Understanding and Harnessing the Potential White Paper

AI: UNDERSTANDING AND HARNESSING THE POTENTIAL WIRELESS & DIGITAL SERVICES AI: UNDERSTANDING AND HARNESSING THE POTENTIAL WHITE PAPER CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ..............................................................................................................................................................................02 1. THE PRODUCTIVITY CONUNDRUM: WILL AI HELP US BREAK INTO A NEW CYCLE? ...........................................................05 1.1 Global productivity growth is faltering ...................................................................................................... 05 1.2 AI has the potential to drive productivity improvements and hence economic growth .................................... 06 2. AI FUTURES ........................................................................................................................................................................11 2.1 Replacing the smartphone with a ubiquitous voice assistant ....................................................................... 11 2.2 Your AI powered personal digital assistant ............................................................................................... 12 2.3 Is AI the missing piece for a truly smart city? ........................................................................................... 14 2.4 City of the future ................................................................................................................................... 16 2.5 Giving medics more time to care ............................................................................................................ -

Circuit Breakers and New Market Structure Realities

Circuit Breakers and New Market Structure Realities China’s dramatic and short-lived But there are questions about whether regulators have been able to keep up with today’s high-speed markets, with one experience with market circuit trader likening them to police on bicycles trying to catch breakers at the start of the New Year Ferraris.1 Regulators themselves have admitted as much. Testifying before the US Senate Committee on Banking after has revived debate about whether the Flash Crash of 2010, former SEC Chairwoman Mary such market interventions do more Schapiro said: “One of the challenges that we face in recreating the events of May 6 is the reality that the technologies used for harm than good, as regulators and market oversight and surveillance have not kept pace with the market participants around the world technology and trading patterns of the rapidly evolving and expanding securities markets.”2 continue to grapple with new market In response, a growing number of equity and equity-related structure realities and the law of markets (e.g., futures and listed options) around the world have introduced circuit breakers in the form of stock-specific and unintended consequences. market-wide trading halts as well as price limit bands in order to stabilize markets when, as the SEC has said, “severe market While many developments in modern equity markets have price declines reach levels that may exhaust market liquidity.”3 benefited investors in the form of greater efficiency and lower The 10 largest (by value traded) equity markets around the costs, they have also led to highly complex and fragmented world have already implemented or are planning to introduce markets. -

High Frequency Trading and Hard Information

Finance and Economics Discussion Series Divisions of Research & Statistics and Monetary Affairs Federal Reserve Board, Washington, D.C. Machines vs. Machines: High Frequency Trading and Hard Information Yesol Huh 2014-33 NOTE: Staff working papers in the Finance and Economics Discussion Series (FEDS) are preliminary materials circulated to stimulate discussion and critical comment. The analysis and conclusions set forth are those of the authors and do not indicate concurrence by other members of the research staff or the Board of Governors. References in publications to the Finance and Economics Discussion Series (other than acknowledgement) should be cleared with the author(s) to protect the tentative character of these papers. Machines vs. Machines: High Frequency Trading and Hard Information Yesol Huh∗ Federal Reserve Board First draft: November 2012 This version: March 2014 Abstract In today's markets where high frequency traders (HFTs) both provide and take liquidity, what influ- ences HFTs' liquidity provision? I argue that information asymmetry induced by liquidity-taking HFTs' use of machine-readable information is important. Applying a novel statistical approach to measure HFT activity and using a natural experiment of index inclusion, I show that liquidity-providing HFTs supply less liquidity to stocks that suffer more from this information asymmetry problem. Moreover, when markets are volatile, this information asymmetry problem becomes more severe, and HFTs supply less liquidity. I discuss implications for market-making activity in times of market stress and for HFT regulations. ∗I would like to thank Stefan Nagel, Arthur Korteweg, and Paul Pfleiderer for their feedback and discussions on this paper. I would also like to thank Shai Bernstein, Darrell Duffie, Sebastian Infante, Heather Tookes, Clara Vega, and the seminar participants at the Stanford GSB, Federal Reserve Board, Vanderbilt University, and University of Rochester for helpful suggestions, and NASDAQ for providing the limit order book data. -

Examining the Efficiency, Stability, and Integrity of the U.S

S. HRG. 111–922 EXAMINING THE EFFICIENCY, STABILITY, AND INTEGRITY OF THE U.S. CAPITAL MARKETS JOINT HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON SECURITIES, INSURANCE, AND INVESTMENT OF THE COMMITTEE ON BANKING, HOUSING, AND URBAN AFFAIRS UNITED STATES SENATE AND THE PERMANENT SUBCOMMITTEE ON INVESTIGATIONS OF THE COMMITTEE ON HOMELAND SECURITY AND GOVERNMENTAL AFFAIRS UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED ELEVENTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION ON EXAMINING THE EFFICIENCY, STABILITY, AND INTEGRITY OF THE U.S. CAPITAL MARKETS DECEMBER 8, 2010 Printed for the use of the Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs ( Available at: http://www.fdsys.gov/ U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 65–272 PDF WASHINGTON : 2011 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 COMMITTEE ON BANKING, HOUSING, AND URBAN AFFAIRS CHRISTOPHER J. DODD, Connecticut, Chairman TIM JOHNSON, South Dakota RICHARD C. SHELBY, Alabama JACK REED, Rhode Island ROBERT F. BENNETT, Utah CHARLES E. SCHUMER, New York JIM BUNNING, Kentucky EVAN BAYH, Indiana MIKE CRAPO, Idaho ROBERT MENENDEZ, New Jersey BOB CORKER, Tennessee DANIEL K. AKAKA, Hawaii JIM DEMINT, South Carolina SHERROD BROWN, Ohio DAVID VITTER, Louisiana JON TESTER, Montana MIKE JOHANNS, Nebraska HERB KOHL, Wisconsin KAY BAILEY HUTCHISON, Texas MARK R. WARNER, Virginia JUDD GREGG, New Hampshire JEFF MERKLEY, Oregon MICHAEL F. BENNET, Colorado EDWARD SILVERMAN, Staff Director WILLIAM D. DUHNKE, Republican Staff Director DAWN RATLIFF, Chief Clerk WILLIAM FIELDS, Hearing Clerk SHELVIN SIMMONS, IT Director JIM CROWELL, Editor SUBCOMMITTEE ON SECURITIES, INSURANCE, AND INVESTMENT JACK REED, Rhode Island, Chairman JIM BUNNING, Kentucky, Ranking Republican Member TIM JOHNSON, South Dakota JUDD GREGG, New Hampshire CHARLES E. -

Artemis Capital Q12012 – Volatility at World's

Volatility at World's End Deflation, Hyperinflation and the Alchemy of Risk Note: The following research paper is an excerpt from the First Quarter 2012 Letter to Investors from Artemis Capital Management LLC published on March 30, 2012. Artemis Capital Management, LLC | Volatility at World's End: Deflation, Hyperinflation and the Alchemy of Risk Page 2 520 Broadway, Suite 350 Santa Monica, CA 90401 (310) 496-4526 phone (310) 496-4527 fax www.artemiscm.com [email protected] Volatility at World's End: Deflation, Hyperinflation and the Alchemy of Risk Imagine the world economy as an armada of ships passing through a narrow and dangerous strait leading to the sea of prosperity. Navigating the channel is treacherous for to err too far to one side and your ship plunges off the waterfall of deflation but too close to the other and it burns in the hellfire of inflation. The global fleet is tethered by chains of trade and investment so if one ship veers perilously off course it pulls the others with it. Our only salvation is to hoist our economic sails and harness the winds of innovation and productivity. It is said that de-leveraging is a perilous journey and beneath these dark waters are many a sunken economy of lore. Print too little money and we cascade off the waterfall like the Great Depression of the 1930s... print too much and we burn like the Weimar Republic Germany in the 1920s... fail to harness the trade winds and we sink like Japan in the 1990s. On cold nights when the moon is full you can watch these ghost ships making their journey back to hell.. -

Speculation and Sovereign Debt – an Insidious Interaction

Speculation and Sovereign Debt – An Insidious Interaction Gerald Epstein 1 and Pierre Habbard 2 October 2011 Table of contents INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................................................2 THE RISE OF FINANCIAL SPECULATION ....................................................................................................................3 NEW FORMS OF FINANCIAL SPECULATION POST -CRISIS ..........................................................................................10 THE SOVEREIGN BOND MARKETS ...........................................................................................................................15 WHAT REGULATORY POLICY RESPONSE ?...............................................................................................................18 CONCLUDING REMARKS AND RECOMMENDATIONS ................................................................................................23 REFERENCES .........................................................................................................................................................26 1 Professor of Economics, University of Massachusetts & Co-director, Political Economy Research Institute (PERI). 2 Senior policy advisor, Trade Union Advisory Committee to the OECD. www.ituc-csi.org & www.tuac.org 1/28 Introduction Four years after the financial crisis and near financial collapse of 2008, the world economy again faces the prospect of a deepening economic -

Paradigm Shifts & Unintended Consequences

FIU Law Review Volume 8 Number 1 Article 15 Fall 2012 Paradigm Shifts & Unintended Consequences: The Death of the Specialist, the Rise of High Frequency Trading, & the Problem of Duty-Free Liquidity in Equity Markets Jennifer Victoria Christine Dean Follow this and additional works at: https://ecollections.law.fiu.edu/lawreview Part of the Other Law Commons Online ISSN: 2643-7759 Recommended Citation Jennifer V. Dean, Paradigm Shifts & Unintended Consequences: The Death of the Specialist, the Rise of High Frequency Trading, & the Problem of Duty-Free Liquidity in Equity Markets, 8 FIU L. Rev. 217 (2012). DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.25148/lawrev.8.1.15 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by eCollections. It has been accepted for inclusion in FIU Law Review by an authorized editor of eCollections. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Paradigm Shifts & Unintended Consequences: The Death of the Specialist, the Rise of High Frequency Trading, & the Problem of Duty-Free Liquidity in Equity Markets Jennifer Victoria Christine Dean* I. INTRODUCTION Every business day, hundreds of thousands of people turn on their televisions to watch CNBC.1 Millions more tune in to listen to Bloomberg radio.2 Thousands of men and women get home from work and open brokerage statements received in the day’s mail. These people have one thing in common: they want to know what is happening with the money. The stock market is more than just a place where people buy and sell stocks; the health of the stock market (more specifically the health of the stock marketplace) is both an indi- cator of, and a substantial factor in, the health of the worldwide econ- omy.3 The stock market is more than just some abstraction on the news; it is to financial capitalism what the circulatory system is to the * Jennifer Victoria Christine Dean, J.D., Florida International University College of Law, 2012; B.A., New York University, Gallatin School of Individualized Study, 2002; M.N.M., Florida Atlantic University, 2009. -

SYSTEMIC RISK: WHAT RESEARCH TELLS US and WHAT WE NEED to FIND out Systemic Risk Centre

Systemic Risk Centre SYSTEMIC RISK: WHAT RESEARCH TELLS US AND WHAT WE NEED TO FIND OUT Systemic Risk Centre Published by Systemic Risk Centre The London School of Economics and Political Science Houghton Street London WC2A 2AE All rights reserved. Requests for permission to reproduce the articles should be sent to the editor at the above address. The support of the Economic and Social © Systemic Risk Centre 2015 Research Council (ESRC) in funding the Designed by DesignRaphael Ltd SRC is gratefully acknowledged Illustrations pgs 9/11/20/26/28 by Judith Allan [grant number ES/K002309/1]. 1 SystemicSystemic RiskRisk CentreCentre Key messages The global financial crisis Policy responses The autumn of 2008 was not the first time that the world Laws, rules and regulations drawn up ostensibly to bolster has faced systemic risk. The threat and, at times, its financial stability and limit the build-up of risk can often realisation have been present ever since the first financial become a channel for amplification mechanisms that system was created and they are an inevitable part of any have precisely the opposite effect. This occurs when market-based economy. multiple rules have inconsistent objectives and interact in unpredicted ways. Often these perverse consequences The challenge for can remain hidden until it is too late, and this can occur policy-makers in particular when policies are drafted hastily in response Society faces a difficult dilemma when it comes to to a crisis. systemic risk. We want financial institutions to participate in economic activity and that means taking risk. We also want Financial engineering financial institutions to be safe. -

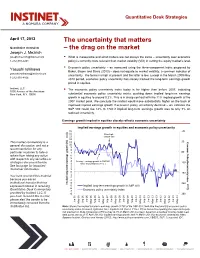

The Uncertainty That Matters Quantitative Strategists – the Drag on the Market Joseph J

Quantitative Desk Strategies April 17, 2013 The uncertainty that matters Quantitative strategists – the drag on the market Joseph J. Mezrich [email protected] ° What is measurable and what matters are not always the same – uncertainty over economic 1-212-310-4241 policy is currently more relevant than market volatility (VIX) in setting the equity market’s level. ° Economic policy uncertainty – as measured using the three-component index proposed by Yasushi Ishikawa Baker, Bloom and Davis (2013) – does not equate to market volatility, a common indicator of [email protected] uncertainty. The former is high at present and the latter is low. Except in the March 2009-May 1-212-310-4106 2010 period, economic policy uncertainty has closely tracked the long-term earnings growth priced in equities. Instinet, LLC ° The economic policy uncertainty index today is far higher than before 2007, indicating 1095 Avenue of the Americas New York, N.Y. 10036 substantial economic policy uncertainty exists, pushing down implied long-term earnings growth in equities to around 0.2%. This is in sharp contrast with the 11% implied growth at the 2007 market peak. We conclude the market would move substantially higher on the back of improved implied earnings growth if economic policy uncertainty declined – we estimate the S&P 500 could rise 12% to 1740 if implied long-term earnings growth rose to only 3% on reduced uncertainty. Earnings growth implied in equities closely reflects economic uncertainty Implied earnings growth in equities and economic policy uncertanity 15 -20 14 Prior high 13 of S&P 500 12 This market commentary is a 11 30 Index Uncertanity Policy Economic general discussion, and not a 10 9 recommendation for any 8 particular customer to take or 7 80 refrain from taking any action 6 with respect to any securities or 5 4 Average earnings growth in S&P500 130 strategies discussed therein.