The Failure of the Criminal Procedure Revolution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

"For" Cranford Former Mayor Barbara Brande Former Mayor Township Committeeman Burt Goodman Dan Aschenbach & CRAI Former Mayor Ron Marotta Former Twp

v • • \ I I Page B-16 CRANFQRD CHRONICLE Thursday, May 24, 1990 SERVING CRANFORDr GARWOOD and KENILWORTH A Forbes Newspaper USPS 136 800 Second Class 50 Cents Vol. 97 No. 22 Published Every Thursday Thursday, May 31,1990 Postage Paid Cranford. N.J. Hartz reveals plans for bank headquarters on Walnut site In brief specified tenant Summit Trust will utilize part of the additional 20 acres in Cranford now owned by General. By Cheryl Moulton existing 350,000-square-foot building for a computer cen- Motors. ".-• Hartz Mountain Industries Friday afternoon announced ter, in addition to the new office building. Hudson Partnership's initial report in January indicated revised plans for the 31-acre former Beecham site on A preliminary draft ordinance to down-zone the South- development of the 31-acre site under existing zoning Library closed Walnut Avenue including building a 75,000-square-foot of- west Gateway area, which includes the Hartz site, was could increase traffic volumes on Walnut Avenue arid. fice building to house the corporate headquarters of Sum- presented to the Township Committee for its review, two Raritan Road, causing a "failure" or "blowout" of the The Cranford Library will mit Trust Co. That development would initially bring 300 weeks ago by the Hudson/Partnership, the planning firm intersection where these roads connect Also indicated close at 5 p,ni tomorrow for employees to the site with a projected growth to 700 over hired by tjhe township, and Harry Pozycld, a land use was "serious adverse impacts" on adjacent residential ar- two weeks to take inventory. -

Appendix File 1958 Post-Election Study (1958.T)

app1958.txt Version 01 Codebook ------------------- CODEBOOK APPENDIX FILE 1958 POST-ELECTION STUDY (1958.T) >> 1958 CONGRESSIONAL CANDIDATE CODE, POSITIVE REFERENCES CODED REFERENCES TO OPPONENT ONLY IN REASONS FOR VOTE. ELSEWHERE CODED REFERENCES TO OPPONENT IN OPPONENT'S CODE. CANDIDATE 00. GOOD MAN, WELL QUALIFIED FOR THE JOB. WOULD MAKE A GOOD CONGRESSMAN. R HAS HEARD GOOD THINGS ABOUT HIM. CAPABLE, HAS ABILITY 01. CANDIDATE'S RECORD AND EXPERIENCE IN POLITICS, GOVERNMENT, AS CONGRESSMAN. HAS DONE GOOD JOB, LONG SERVICE IN PUBLIC OFFICE 02. CANDIDATE'S RECORD AND EXPERIENCE OTHER THAN POLITICS OR PUBLIC OFFICE OR NA WHETHER POLITICAL 03. PERSONAL ABILITY AND ATTRIBUTES. A LEADER, DECISIVE, HARD-WORKING, INTELLIGENT, EDUCATED, ENERGETIC 04. PERSONAL ABILITY AND ATTRIBUTES. HUMBLE, SINCERE, RELIGIOUS 05. PERSONAL ABILITY AND ATTRIBUTES. MAN OF INTEGRITY. HONEST. STANDS UP FOR WHAT HE BELIEVES IN. PUBLIC SPIRITED. CONSCIENTIOUS. FAIR. INDEPENDENT, HAS PRINCIPLES 06. PERSONAL ATTRACTIVENESS. LIKE HIM AS A PERSON, LIKABLE, GOOD PERSONALITY, FRIENDLY, WARM 07. PERSONAL ATTRACTIVENESS. COMES FROM A GOOD FAMILY. LIKE HIS FAMILY, WIFE. GOOD HOME LIFE 08. AGE, NOT TOO OLD, NOT TOO YOUNG, YOUNG, OLD 09. OTHER THE MAN, THE PARTY, OR THE DISTRICT 10. CANDIDATE'S PARTY AFFILIATION. HE IS A (DEM) (REP) 11. I ALWAYS VOTE A STRAIGHT TICKET. TO SUPPORT MY PARTY 12. HE'S DIFFERENT FROM (BETTER THAN) MOST (D'S) (R'S) 13. GOOD CAMPAIGN. GOOD SPEAKER. LIKED HIS CAMPAIGN, Page 1 app1958.txt CLEAN, HONEST. VOTE-GETTER 14. HE LISTENS TO THE PEOPLE BACK HOME. HE DOES (WILL DO) WHAT THE PEOPLE WANT 15. HE MIXES WITH THE COMMON PEOPLE. -

National Association of Former United States Attorneys

National Association of Former United States Attorneys March 2010 SEATTLE, WASHINGTON Officers 2009 ANNUAL CONFERENCE President Richard A. Rossman ED Michigan President Elect William L. Lutz New Mexico Vice President Richard H. Deane, Jr. ND Georgia Secretary Jay B. Stephens District of Columbia Treasurer Don Stern Massachusetts Past President Michael D. McKay WD Washington History Committee Chairman John Clark WD Texas Membership Committee Chairman Jack Selden ND Alabama Directors Class of 2010 Wayne Budd Massachusetts J. A. “Tony “ Canales SD Texas Douglas Jones ND Alabama Andrea Ordin MD California Matthew Orwig ED Texas Former Deputy AG William Class of 2011 Ruckelshaus Gives Riveting Margaret Currin ED North Carolina Walter Holton MD North Carolina Speech Concerning Saturday John McKay WD Washington Debra Wong Yang CD California Night Massacre Class of 2012 Jim Brady WD Michigan The 2009 NAFUSA Annual Conference Dinner Speaker, William Ruckel- Terry Flynn WD New York Rick Hess SD Illinois shaus, who served as Acting Director of the FBI and as Deputy Attorney Gen- Jose Rivera Arizona Chuck Stevens ED California eral in the Nixon Administration, gave his first speech recounting the events when he and Attorney General Elliott Richardson resigned on Saturday, Octo- Executive Director ber 20, 1973, rather than follow a direct order from the president to fire Water- Ronald G. Woods SD Texas 5300 Memorial - Suite 1000 gate Special Prosecutor Archibald Cox. Houston, TX 77007 Ruckelshaus, now 77 and living in Seattle, agreed to the request of his Phone: 713-862-9600 Fax: 713-864-8738 Email: [email protected] friend, NAFUSA President Mike McKay, to speak on the subject at the NA- FUSA Annual Conference Dinner on Saturday, October 3, 2009. -

Thomas E. Dewey and Earl Warren: the Rise of the Twentieth Century Urban Prosecutor

California Western Law Review Volume 28 Number 1 Article 2 1991 Thomas E. Dewey and Earl Warren: The Rise of the Twentieth Century Urban Prosecutor Lawrence Fleischer Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.cwsl.edu/cwlr Recommended Citation Fleischer, Lawrence (1991) "Thomas E. Dewey and Earl Warren: The Rise of the Twentieth Century Urban Prosecutor," California Western Law Review: Vol. 28 : No. 1 , Article 2. Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.cwsl.edu/cwlr/vol28/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by CWSL Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in California Western Law Review by an authorized editor of CWSL Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CALIFORNIA WESTERN Fleischer: Thomas E. Dewey and Earl Warren: The Rise of the Twentieth Centur LAW REVIEW VOLUME 28 1991-1992 NUMBER 1 THOMAS E. DEWEY AND EARL WARREN: THm RISE OF THE TWENTIETH CENTURY URBAN PROSECUTOR LAWRENCE FLEISCHER* INTRODUCTION The study of the American urban prosecutor, a key political-legal officer who carries the immense power of "prosecutorial discretion," has yet to attract serious historical research. A review of the published literature suggests the first crucial period of development occurred during the Jacksonian period when the office broke free of its traditional administrative role as the adjunct of the court. During this period the local urban prosecutor became an elected official.1 This unmoored the office from the anchor of the judiciary and set it sailing into the realm of politics. Essential- ly, this set the standard throughout the nineteenth and the early part of the twentieth centuries of an office beholden to the electorate in the most intimate political sense, and established the office as the keystone of the criminal justice system. -

Robert Charles Hill Papers

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf0p3000wh Online items available Register of the Robert Charles Hill papers Finding aid prepared by Dale Reed and James Lake Hoover Institution Library and Archives © 1999 434 Galvez Mall Stanford University Stanford, CA 94305-6003 [email protected] URL: http://www.hoover.org/library-and-archives Register of the Robert Charles 79067 1 Hill papers Title: Robert Charles Hill papers Date (inclusive): 1929-1978 Collection Number: 79067 Contributing Institution: Hoover Institution Library and Archives Language of Material: English Physical Description: 183 manuscript boxes, 73 envelopes, 29 oversize boxes, 1 oversize folder, 9 motion picture film reels, 4 sound tape reels(125.0 Linear Feet) Abstract: Speeches and writings, correspondence, reports, clippings, other printed matter, photographs, motion picture film, and sound recordings relating to conditions in and American relations with Latin America and Spain, American foreign policy and domestic politics, and the Republican Party. Digital copies of select records also available at https://digitalcollections.hoover.org. Creator: Hill, Robert Charles, 1917-1978 Hoover Institution Library & Archives Access The collection is open for research; materials must be requested at least two business days in advance of intended use. Publication Rights For copyright status, please contact the Hoover Institution Library & Archives. Acquisition Information Acquired by the Hoover Institution Library & Archives in 1979. Preferred Citation [Identification of item], Robert Charles Hill papers, [Box no., Folder no. or title], Hoover Institution Library & Archives. Alternate Forms Available Digital copies of select records also available at https://digitalcollections.hoover.org. 1917 September Born, Littleton, New Hampshire 30 1941-1944 Washington, D.C., representative, New England Shipbuilding Corporation 1944-1945 U.S. -

Centurions in Public Service Preface 11 Acknowledgments Ment from the Beginning; Retired Dewey Ballantine Partner E

centurions in pu blic service Particularly as Presidents, Supreme Court Justices & Cabinet Members by frederic s. nathan centurions in pu blic service Particularly as Presidents, Supreme Court Justices & Cabinet Members by frederic s. nathan The Century Association Archives Foundation, New York “...devotion to the public good, unselfish service, [an d] never-ending consideration of human needs are in them - selves conquering forces. ” frankli n delano roosevelt Rochester, Minnesota, August 8, 1934 Table of Contents pag e 9 preface 12 acknowle dgments 15 chapte r 0ne: Presidents, Supreme Court Justices, and Cabinet Members 25 charts Showing Dates of Service and Century Association Membership 33 chapte r two: Winning World War II 81 chapte r three: Why So Many Centurions Entered High Federal Service Before 1982 111 chapte r four: Why Centurion Participation Stopped and How It Might Be Restarted 13 9 appendix 159 afterw0rd the century association was founded in 1847 by a group of artists, writers, and “amateurs of the arts” to cultivate the arts and letters in New York City. They defined its purpose as “promoting the advancement Preface of art and literature by establishing and maintaining a library, reading room and gallery of art, and by such other means as shall be expedient and proper for that purpose.” Ten years later the club moved into its pen ul - timate residence at 109 East 15 th Street, where it would reside until January 10, 1891 , when it celebrated its an - nual meeting at 7 West 43 rd Street for the first time. the century association archives founda - tion was founded in 1997 “to foster the Foundation’s archival collection of books, manuscripts, papers, and other material of historical importance; to make avail able such materials to interested members of the public; and to educate the public regarding its collec - tion and related materials.” To take these materials from near chaos and dreadful storage conditions to a state of proper conservation and housing, complete with an online finding aid, is an accomplishment of which we are justly proud. -

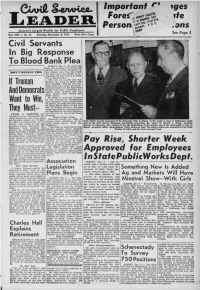

If Truman and Democrats Want to Win, They Must

Important r' iges —CUnfi- B-eAAfhuu ForeC ite Person:'^i .ons Americans Largest Weekly for Public Employees See Page 3 Yol. XIII — No. 11 Tuesday, December 4, 1951 Price Five CenU Civil Servants In Big Response To Blood Bank Plea ALBANY, Dec. 3—So great has been the response to a blood call among civil service employees in no:N'T RKPKAT THIS the Albany area that last week the Red Cross was unable to ac- comodate all who wished to make their contributions. "We sent out a letter only last Friday," Dr. John K. Miller told If Truman The LEADER, "and the civil ser- vants must have made life miser- able but happy for the Red Cross people with their tremendous re- sponse. That response was, I'm And Democrats sure, greater than among any other group." Dr. Miller is Associate Director of the Division of Laboratories Want to Win, and Research, State Department of Health. He holds the post, also, of State Blood Officer in the Of- fice of Medical Defense, and has They Must- been appointed by Governor Dew- ey Chairman of the State Employ- FRANK E, McKINNEy, new ees Division of the Blood Donor chairman of the Democratic Na- Program. tional Committee, last week came Dewey Urges Action out formally against sin. "A pub- Governor Dewey last week, in urging public employees to be- Stat* Safety Awards presented at tke University Clab in Albany. In ttie center Is Jesse B. MeFariand, pretl^ lic office is a public trust," he re- dent of the Civil Service Employees Association, presenting the award to Harold L Briggs, assistant peated, with credit to the late come blood donors, made this president Grover Cleveland. -

RFK#3, 2/25/1970 Administrative Information Creator: John J. Burns Interviewer

John J. Burns, Oral History Interview – RFK#3, 2/25/1970 Administrative Information Creator: John J. Burns Interviewer: Roberta W. Greene Date of Interview: February 25, 1970 Location: New York, New York Length: 30 pages Biographical Note Burns was Mayor of Binghamton, NY (1958-1966); chairman of the New York State Democratic Party (1965-1973); delegate to the Democratic National Convention (1968); and a Robert Kennedy campaign worker (1968). In this interview, he discusses Lyndon Baines Johnson’s hostility towards Robert F. Kennedy (RFK) and RFK’s associates; and Robert F. Kennedy’s involvement in the 1965 New York City mayoral race, the 1966 New York gubernatorial race, and the 1967 New York constitutional convention, among other issues. Access Open. Usage Restrictions Copyright of these materials have passed to the United States Government upon the death of the interviewee. Users of these materials are advised to determine the copyright status of any document from which they wish to publish. Copyright The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Under certain conditions specified in the law, libraries and archives are authorized to furnish a photocopy or other reproduction. One of these specified conditions is that the photocopy or reproduction is not to be “used for any purpose other than private study, scholarship, or research.” If a user makes a request for, or later uses, a photocopy or reproduction for purposes in excesses of “fair use,” that user may be liable for copyright infringement. This institution reserves the right to refuse to accept a copying order if, in its judgment, fulfillment of the order would involve violation of copyright law. -

Abrams 1 for the People?: the Role of Prosecutorial Misconduct in The

Abrams 1 For the People?: The Role of Prosecutorial Misconduct in the Rise of Progressive Prosecution in Brooklyn, 1964-2019 Kayla Abrams Undergraduate Senior Thesis Department of History Columbia University March 2021 Seminar Advisor: Professor Samuel Roberts Second Reader: Professor Kellen Funk Abrams 2 Abstract In this paper, I investigate how “progressive prosecution” arose in Brooklyn in the early 2010s. I argue that “progressive prosecution” emerged in reaction to the prosecutorial misconduct that characterized the Office for most of its history. To prove this, I show that the history of the Brooklyn DA’s Office is one in which the Office was constantly combating the reality and perception of malpractice. While the Office was able to limit corruption when it professionalized in the late 1960s, it was unable to do the same with prosecutorial misconduct due to a lack of political pressure or the respective DA’s “insider” status—and often both. Therefore, Ken Thompson was able to capitalize on this inability to deal with prosecutorial misconduct throughout those fifty years, along with a growing national desire for a less punitive criminal justice system, to bring progressive prosecution to Brooklyn. As Brooklyn is the fifth largest jurisdiction in the country, with an estimated population of over 2.5 million people, any change in Brooklyn always has national implications. However, while my analysis has this specific regional focus, the story I tell is not just a Brooklyn story. Although every Office does have their own unique history, the factors I discuss – continual prosecutorial misconduct, changing public opinion on the punitiveness of the justice system, and “progressive” candidates – were present in other cities who in the ensuing decade have similarly elected “progressive prosecutors”, such as Chicago, Philadelphia, Boston, St. -

Hon. John F. Keenan U.S

Judicial Profile Hon. John F. Keenan U.S. District Judge for the Southern District of New York by Ross Galin or generations of lawyers, the Southern DistJict of New York has been the "Mother Court," and not just because it is the nation's oldest federal tribunal- the fu'S t to be seated ...,... under the Judiciary Act of 1789. The sobriquet speaks equally to the iconic jwists who have presided over the distlict's landmark cases- judges like John F. Keenan, who since 1983 has honored and extended Ross Galin is a partrurr the Mother Court's tradition of legal excellence and ·ir1. the New Yo1·k office oj judicial independence, and in so doing earned the rev O'Melven y & Myers LLP He rcyn·esents coryJora erence of those who have served with and appeared tions and individual before him. "!do not know of another judge who is as clients in civil, 1·egutato uniformly liked as he is," otTers former colleague and ry, cmd criminal matters longtime friend Michael Armstrong, now of McLaugh and pmvides compli lin & Stern. "ln anyone's list of the best three judges ance advice. Ross's cli ents inclu.de pharmace'LL· in the Southern Dist1ict of New York at any time over tical and medical tlevice the past 25 yeal'S, John Keenan is going to be one of companies and thei'r them." exeG'ulives and employ Yet Judge Keenan's time on the bench is only one ees, as weU as financial part of a distinguished legal career that has spanned the grand jury and about Gurfein and the assistants seroices institutions. -

Notre Dame Alumni Headquarters: 329 Adtn'mi'stration Bldg., Notre Dame

The Archives of The University of Notre Dame 607 Hesburgh Library Notre Dame, IN 46556 574-631-6448 [email protected] Notre Dame Archives: Alumnus The Notre Dame Alumnus Vol. V. Contents for September, 1926 No. 1 The Notre Dame of Today 3 Changes in the Order 6 The President's Page 8 Father Vagnier, '68, Dies 12 Educational Eelations With Alumni 12 N. D. Journalist Recognized 17 The Alumni Clubs 18 Athletics 20 The Alumni 24 The magazine is published monthly during the scholastic year by the Alumni Association of the University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, Indiana. The subscription price is 32.00 a year; the price of single copies is 25 cents. The annual alumni dues of S5.00 include a year's subscription to The Alumnus. Entered as second-class matter January 1, 1923, at the post ofSce at Notre Dame, Indiana, under the Act of March 3, 1897. All corres pondence should be addressed to The Notre Dame Alumnus, Box 81, Notre Dame, Indiana. JAMES E. ARMSTRONG, '25, Editor The Alumni Association — of the — University of Notre Dame Alumni Headquarters: 329 Adtn'mi'stration Bldg., Notre Dame. James E. Armstrong '25, General Secretary. ALUMNI BOARD EEV. M. L. MORIARTY, '10 Honorary President DANIEL J. O'CONNOR, '05 President JAMES E. SANFORD, '15 Vice-President' JAMES E. ARMSTRONG, '25 Secretary WALTER L. DUNCAN, '12 Treasurer THOMAS J. MCKEON, '90 Director EDWIN C. MCHUGH, '13 Director JOSEPH M. HALEY, '99 Director ALFRED C. RYAN, '20 Director IM CD CO THE NOTRE DAME OP TODAY •l.^^tv^n:-^•ep;JlSlijw.:m.;.^ife«^ll^^ :-• ,a>^ The Notre Dame of Today HE Notre Dame of Today is the Notre crowds who will patronize the games of the TDame of Yesterday and of Tomorrow. -

JUDICIAL NOTICE Issue 7 L Summer 2011 I 7 E U S S L

Judicial Notice A PERIODICaL OF NEW YORK COURT HISTORy JUDICIAL NOTICE ISSUE 7 l SUMMER 2011 i s s u e 7 l s People v. Croswell Paul McGrath u m m e r 2 0 1 1 l Ballot Reform and the Election of 1891 l David Sheridan Charles David Breitel l W.B. Benkard ThE HISTORICaL SOCIETy OF ThE COURTS OF ThE STaTE OF NEW YORK TABLE CONTENTS of ISSUE 7 SUMMER 2011 pg 3 pg 5 pg 21 pg 39 FEATURED ARTICLES Pg 5 People v. Croswell by Paul McGrath Pg 21 Ballot Reform and the Election of 1891 by David Sheridan Pg 39 Charles David Breitel by James W.B. Benkard DEPARTMENTS Pg 2 From the Editor-in-Chief Pg 3 A Gala Opening Statement Pg 49 The David A. Garfinkel Essay Contest Pg 58 A Look Back Pg 61 Society Officers and Trustees Pg 61 Society Membership Pg 64 Become a Member Pg 66 Courthouse Art JUDICIAL NOTICE l 1 F ROM THE EDITOR-IN-CHIEF n 2003, on the occasion of the inaugural issue of this publication, the Society’s founders, Judith S. Kaye and Albert M. Rosenblatt, declared that our mission was to “cast the net” for Dearhistorical “riches” aboutMembers New York’s courts. I am pleased to say that the issue of Judicial Notice you now hold in your hands lives up to that standard. IIn the pages that follow, you will find original scholarship about significant moments, figures and symbols in New York history. While the riches you will read about in these pages are largely centered on scholarly history, we are privileged as well, as members of the Society, to enjoy a remarkable personal collegiality; we begin this issue with a review of our Galas, honoring three pillars of our court system: the judges, the lawyers, and the court staff.