Breastfeeding and Breast Milk – from Biochemistry to Impact

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Common Breastfeeding Questions

Common Breastfeeding Questions How often should my baby nurse? Your baby should nurse 8-12 times in 24 hours. Baby will tell you when he’s hungry by “rooting,” sucking on his hands or tongue, or starting to wake. Just respond to baby’s cues and latch baby on right away. Every mom and baby’s feeding patterns will be unique. Some babies routinely breastfeed every 2-3 hours around the clock, while others nurse more frequently while awake and sleep longer stretches in between feedings. The usual length of a breastfeeding session can be 10-15 minutes on each breast or 15-30 minutes on only one breast; just as long as the pattern is consistent. Is baby getting enough breastmilk? Look for these signs to be sure that your baby is getting enough breastmilk: Breastfeed 8-12 times each day, baby is sucking and swallowing while breastfeeding, baby has 3- 4 dirty diapers and 6-8 wet diapers each day, the baby is gaining 4-8 ounces a week after the first 2 weeks, baby seems content after feedings. If you still feel that your baby may not be getting enough milk, talk to your health care provider. How long should I breastfeed? The World Health Organization and the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends mothers to breastfeed for 12 months or longer. Breastmilk contains everything that a baby needs to develop for the first 6 months. Breastfeeding for at least the first 6 months is termed, “The Golden Standard.” Mothers can begin breastfeeding one hour after giving birth. -

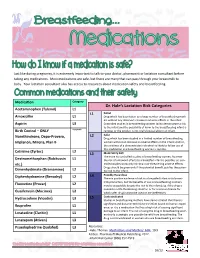

Dr. Hale's Lactation Risk Categories

Just like during pregnancy, it is extremely important to talk to your doctor, pharmacist or lactation consultant before taking any medications. Most medications are safe, but there are many that can pass through your breastmilk to baby. Your lactation consultant also has access to resources about medication safety and breastfeeding. Medication Category Dr. Hale’s Lactation Risk Categories Acetaminophen (Tylenol) L1 L1 Safest Amoxicillin L1 Drug which has been taken by a large number of breastfeeding moth- ers without any observed increase in adverse effects in the infant. Aspirin L3 Controlled studies in breastfeeding women fail to demonstrate a risk to the infant and the possibility of harm to the breastfeeding infant is Birth Control – ONLY Acceptable remote; or the product is not orally bioavailable in an infant. L2 Safer Norethindrone, Depo-Provera, Drug which has been studied in a limited number of breastfeeding Implanon, Mirena, Plan B women without an increase in adverse effects in the infant; And/or, the evidence of a demonstrated risk which is likely to follow use of this medication in a breastfeeding woman is remote. Cetrizine (Zyrtec) L2 L3 Moderately Safe There are no controlled studies in breastfeeding women, however Dextromethorphan (Robitussin L1 the risk of untoward effects to a breastfed infant is possible; or, con- etc.) trolled studies show only minimal non-threatening adverse effects. Drugs should be given only if the potential benefit justifies the poten- Dimenhydrinate (Dramamine) L2 tial risk to the infant. L4 Possibly Hazardous Diphenhydramine (Benadryl) L2 There is positive evidence of risk to a breastfed infant or to breast- milk production, but the benefits of use in breastfeeding mothers Fluoxetine (Prozac) L2 may be acceptable despite the risk to the infant (e.g. -

Melasma (1 of 8)

Melasma (1 of 8) 1 Patient presents w/ symmetric hyperpigmented macules, which can be confl uent or punctate suggestive of melasma 2 DIAGNOSIS No ALTERNATIVE Does clinical presentation DIAGNOSIS confirm melasma? Yes A Non-pharmacological therapy • Patient education • Camoufl age make-up • Sunscreen B Pharmacological therapy Monotherapy • Hydroquinone or • Tretinoin TREATMENT Responding to No treatment? See next page Yes Continue treatment © MIMSas required Not all products are available or approved for above use in all countries. Specifi c prescribing information may be found in the latest MIMS. B94 © MIMS 2019 Melasma (2 of 8) Patient unresponsive to initial therapy MELASMA A Non-pharmacological therapy • Patient education • Camoufl age make-up • Sunscreen B Pharmacological therapy Dual Combination erapy • Hydroquinone plus • Tretinoin or • Azelaic acid Responding to Yes Continue treatment treatment? as required No A Non-pharmacological therapy • Patient education • Camoufl age make-up • Sunscreen • Laser therapy • Dermabrasion B Pharmacological therapy Triple Combination erapy • Hydroquinone plus • Tretinoin plus • Topical steroid Chemical peels 1 MELASMA • Acquired hyperpigmentary skin disorder characterized by irregular light to dark brown macules occurring in the sun-exposed areas of the face, neck & arms - Occurs most commonly w/ pregnancy (chloasma) & w/ the use of contraceptive pills - Other factors implicated in the etiopathogenesis are photosensitizing medications, genetic factors, mild ovarian or thyroid dysfunction, & certain cosmetics • Most commonly aff ects Fitzpatrick skin phototypes III & IV • More common in women than in men • Rare before puberty & common in women during their reproductive years • Solar & ©ultraviolet exposure is the mostMIMS important factor in its development Not all products are available or approved for above use in all countries. -

The Key to Increasing Breastfeeding Duration: Empowering the Healthcare Team

The Key to Increasing Breastfeeding Duration: Empowering the Healthcare Team By Kathryn A. Spiegel A Master’s Paper submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Public Health in the Public Health Leadership Program. Chapel Hill 2009 ___________________________ Advisor signature/printed name ________________________________ Second Reader Signature/printed name ________________________________ Date The Key to Increasing Breastfeeding Duration 2 Abstract Experts and scientists agree that human milk is the best nutrition for human babies, but are healthcare professionals (HCPs) seizing the opportunity to promote, protect, and support breastfeeding? Not only are HCPs influential to the breastfeeding dyad, they hold a responsibility to perform evidence-based interventions to lengthen the duration of breastfeeding due to the extensive health benefits for mother and baby. This paper examines current HCPs‘ education, practices, attitudes, and extraneous factors to surface any potential contributing factors that shed light on necessary actions. Recommendations to empower HCPs to provide consistent, evidence-based care for the breastfeeding dyad include: standardized curriculum in medical/nursing school, continued education for maternity and non-maternity settings, emphasis on skin-to-skin, enforcement of evidence-based policies, implementation of ‗Baby-Friendly USA‘ interventions, and development of peer support networks. Requisite resources such as lactation consultants as well as appropriate medication and breastfeeding clinical management references aid HCPs in providing best practices to increase breastfeeding duration. The Key to Increasing Breastfeeding Duration 3 The key to increasing breastfeeding duration: Empowering the healthcare team During the colonial era, mothers breastfed through their infants‘ second summer. -

Breastfeeding Contraindications

WIC Policy & Procedures Manual POLICY: NED: 06.00.00 Page 1 of 1 Subject: Breastfeeding Contraindications Effective Date: October 1, 2019 Revised from: October 1, 2015 Policy: There are very few medical reasons when a mother should not breastfeed. Identify contraindications that may exist for the participant. Breastfeeding is contraindicated when: • The infant is diagnosed with classic galactosemia, a rare genetic metabolic disorder. • Mother has tested positive for HIV (Human Immunodeficiency Syndrome) or has Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome (AIDS). • The mother has tested positive for human T-cell Lymphotropic Virus type I or type II (HTLV-1/2). • The mother is using illicit street drugs, such as PCP (phencyclidine) or cocaine (exception: narcotic-dependent mothers who are enrolled in a supervised methadone program and have a negative screening for HIV and other illicit drugs can breastfeed). • The mother has suspected or confirmed Ebola virus disease. Breastfeeding may be temporarily contraindicated when: • The mother is infected with untreated brucellosis. • The mother has an active herpes simplex virus (HSV) infection with lesions on the breast. • The mother is undergoing diagnostic imaging with radiopharmaceuticals. • The mother is taking certain medications or illicit drugs. Note: mothers should be provided breastfeeding support and a breast pump, when appropriate, and may resume breastfeeding after consulting with their health care provider to determine when and if their breast milk is safe for their infant and should be provided with lactation support to establish and maintain milk supply. Direct breastfeeding may be temporarily contraindicated and the mother should be temporarily isolated from her infant(s) but expressed breast milk can be fed to the infant(s) when: • The mother has untreated, active Tuberculosis (TB) (may resume breastfeeding once she has been treated approximately for two weeks and is documented to be no longer contagious). -

Skin Care, Hair Care and Cosmetic Treatments in Pregnancy and Breastfeeding

Skin Care, Hair Care and Cosmetic Treatments in Pregnancy and Breastfeeding Information in this leaflet is general in nature and should not take the place of advice from your health care provider. With every pregnancy there is a 3 to 5% risk of having a baby with a birth defect. Issues for pregnancy Many pregnant women have skin and hair concerns just as they did before pregnancy. Sometimes conditions such as acne actually worsen during pregnancy because of hormonal changes and often women notice darkening of their skin (melasma). However, due to concern about potentially hazardous exposures to their unborn babies, pregnant women are often uncertain about which products are safe for them to use. Generally cosmetic treatments are discretionary (not medically necessary) and if safety is uncertain, women should consider whether the product or treatment is really required. There are several considerations when evaluating whether a specific skin or hair product is unsafe in pregnancy. Firstly, the active ingredient in the product needs to be considered unsafe. Secondly, it also has to be able to reach the unborn baby in its mother’s womb by inhalation or absorption through the mother’s skin (topical application). Although there is often limited information about the actual safety of specific ingredients in skin products during pregnancy, if it is known that skin absorption is minimal then the exposure to the unborn baby is generally insignificant and the product or treatment is regarded as safe. Below is a summary of current advice. Cosmetics, Moisturisers and other Skin Care Products Cosmetics and over the counter skin products generally contain ingredients that are unlikely to be harmful in pregnancy as they are used by applying to the skin (rather than swallowing a tablet). -

Breastfeeding Matters

Breastfeeding Matters An important guide for breastfeeding families ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Best Start by Health Nexus would like to thank the Public Health Units of Ontario who supported the creation and development of this provincial resource and generously shared their resources and expertise. We would also like to thank the parents and the experts who provided input for this booklet. Final review was done by Marg La Salle, RN, BScN, IBCLC, and BFI Lead Assessor. The information in this booklet is current at the time of production but information can change over time. Every effort will be made to ensure the information remains current. Throughout this resource, gender-specific language such as “woman”, “women” and “mother” is used in order to accurately cite the research referred to. We intend these terms to refer to all childbearing individuals, regardless of their gender identity or sexual orientation. Funded by the Government of Ontario. Table of Contents SECTION 1 .......................... 3 SECTION 4 ........................ 27 The Importance of Breastfeeding Important Things to Know • Risks of Not Breastfeeding • Waking a Sleepy Baby • Your Breastfeeding Rights • Calming a Fussy Baby • The Baby-Friendly Initiative • Burping Your Baby • Making an Informed Decision • Growth Spurts • Family Support • Sore Nipples • Peer Support • Using a Pacifier (Soother) • Engorgement SECTION 2 ........................ 11 • Storing Your Breast Milk Helping Your Baby Get a Good Start • Skin-to-Skin SECTION 5 ........................ 33 • Safe Positioning -

In a New Video, the Mom of Two Reveals the Dark Spot Toner She Swears By

In a new video, the mom of two reveals the dark spot toner she swears by. Hilary Duff, who is mom to Luca, 7, and Banks, 1, recently shared her “busy mom makeup routine” with Vogue — including the product she uses to treat her pregnancy melasma. “I’m a busy mom,” the actress says in the video. “I don’t have a ton of time to do my makeup, but this version today is on a day when I have my kids but also have a couple of meetings and I want to look like I put some effort in.” Duff starts off her routine by washing her hands or using hand sanitizer. She then reaches for her toner. “One really ‘cool’ thing that happened to me when I had babies is I got melasma,” she shared, pointing to a dark spot near the top of her forehead. “Every day, I say a little prayer that it’s taking care of that dark spot right there,” she says, rubbing on Ole Henriksen’s Glow2OH Dark Spot Toner ($29; sephora.com). Other products in Duff's kit include REN Clean Skincare Keep Young and Beautiful Anti-Aging Eye Cream ($44; sephora.com) and Perricone MD No Makeup Foundation Broad Spectrum SPF 20 ($60; ulta.com). What is melasma, exactly? Melasma is a common skin condition that causes brown to gray-brown patches to develop, usually on the face. Also referred to as the mask of pregnancy, melasma appears when a sharp rise in estrogen and progesterone levels stimulates excess melanin production, also known as hyperpigmentation. -

Breastfeeding Support Credentials

Who’s Who? A glance at breastfeeding support in the United States Lactation support is often needed to help mothers initiate and continue breastfeeding. There are many kinds of help available for breastfeeding mothers including peer counselors, certified breastfeeding educators and counselors, and lactation professionals such as the International Board Certified Lactation Consultant (IBCLC®). Breastfeeding support is valuable for a variety of reasons, from encouragement and emotional support to guidance and assistance with complex clinical situations. Mothers benefit from all kinds of support, and it is important to receive the right kind at the right time. The breastfeeding support categories listed below each play a vital role in providing care to mothers and babies. Breastfeeding Support Prerequisites Training Required Scope of Practice Type • 90 hours of lactation-specific education Recognized health Provide professional, • College level health science professional or evidence based, clinical courses Professional satisfactory completion lactation management; • 300-1000 clinical practice hours (International Board Certified of collegiate level educate families, health Lactation Consultant, IBCLC®) • Successful completion of a health sciences professionals and others criterion-referenced exam offered coursework. about human lactation. by an independent international board of examiners. Certified • 20-120 hours of classroom training Provide education and • Often includes a written exam guidance for families (i.e. Certified Lactation N/A Counselor, Certified or “certification” offered by the on basic breastfeeding Breastfeeding Educator, etc. ) training organization issues. Provide breastfeeding information, Peer Personal breastfeeding • 18-50 hours of classroom training encouragement, and (i.e. La Leche League, WIC experience. Peer Counselor, etc.) support to those in their community. Copyright © 2016 by USLCA. -

MATERNAL & CHILD HEALTH Technical Information Bulletin

A Review of the Medical Benefits and Contraindications to Breastfeeding in the United States Ruth A. Lawrence, M.D. Technical Information Bulletin Technical MATERNAL & CHILD HEALTH MATERNAL October 1997 Cite as Lawrence RA. 1997. A Review of the Medical Benefits and Contraindications to Breastfeeding in the United States (Maternal and Child Health Technical Information Bulletin). Arlington, VA: National Center for Education in Maternal and Child Health. A Review of the Medical Benefits and Contraindications to Breastfeeding in the United States (Maternal and Child Health Technical Information Bulletin) is not copyrighted with the exception of tables 1–6. Readers are free to duplicate and use all or part of the information contained in this publi- cation except for tables 1–6 as noted above. Please contact the publishers listed in the tables’ source lines for permission to reprint. In accordance with accepted publishing standards, the National Center for Education in Maternal and Child Health (NCEMCH) requests acknowledg- ment, in print, of any information reproduced in another publication. The mission of the National Center for Education in Maternal and Child Health is to promote and improve the health, education, and well-being of children and families by leading a nation- al effort to collect, develop, and disseminate information and educational materials on maternal and child health, and by collaborating with public agencies, voluntary and professional organi- zations, research and training programs, policy centers, and others to advance knowledge in programs, service delivery, and policy development. Established in 1982 at Georgetown University, NCEMCH is part of the Georgetown Public Policy Institute. NCEMCH is funded primarily by the U.S. -

Breastfeeding Promotion Committee Terms of Reference

Breastfeeding Promotion Committee Terms of Reference VISION We envision a region where breastfeeding is the cultural norm. PURPOSE The purpose of the Breastfeeding Promotion Committee (BPC) is to protect, promote and support breastfeeding in the Champlain and South East LHINs. VALUES We follow and promote the Baby Friendly Initiative 10 Steps1 and the International Code of Marketing Breastmilk Substitutes2: o We advocate for maternal-newborn dyad care: togetherness, no unnecessary separation in healthcare organizations and in the community. o We coordinate and collaborate across the circle of care to promote effective breastfeeding services. The circle of care includes all health care and community workers supporting clients to breastfeed in hospitals, community agencies and private practices. o We promote breastfeeding education across the lifespan to families, communities and health care professionals. o We promote breastfeeding across the reproductive continuum, from pre-conception to childhood. Clients – parents, babies and families – are at the centre of our work. Our actions are based on the best available evidence. We support and promote informed decision-making about infant feeding and respect the decisions that clients make. ACCOUNTABILITY The Breastfeeding Promotion Committee reports to CMNRP’s Advisory Committee. ROLES and RESPONSIBILITIES Determine and prioritize goals in conjunction with CMNRP’s Strategic Plan priorities and timelines. Monitor and review regional breastfeeding data to identify strengths and gaps in performance. Identify and recommend strategies to address gaps and improve services. Create short-term workgroups to address specific goals. Develop project charters that specify the scope, objectives, action plans, deliverables and timelines for each workgroup. Provide BPC reports to CMNRP’s Advisory Committee. -

Tips for Sore/Cracked Nipples

Tips for Sore/Cracked Nipples Nipples can become sore and cracked due to many reasons such as a shallow latch, tongue-tie or other anatomical variations, thrush, a bite, milk blister, etc. Keep in mind that one of the most important factors in healing is to correct the source of the problem. Continue to work on correct latch and positioning, thrush treatment, etc. as you treat the symptoms, and talk to a board certified lactation consultant (IBCLC). During the nursing session • Breastfeed from the uninjured (or less injured) side first. Baby will tend to nurse more gently on the second side offered. • Experiment with different breastfeeding positions to determine which is most comfortable. • If breastfeeding is too painful, it is very important to express milk from the injured side to reduce the risk of mastitis and to maintain supply. Pump on a low setting. Salt water rinse after nursing This special type of salt water, called normal saline, has the same salt concentration as tears and should not be painful to use. To make your own normal saline solution: Mix 1/2 teaspoon of salt in one cup (8 oz) of warm water. Make a fresh supply each day to avoid bacterial contamination. • After breastfeeding, soak nipple(s) in a small bowl of warm saline solution for a minute or so–long enough for the saline to get onto all areas of the nipple. Avoid prolonged soaking (more than 5-10 minutes) that “super” hydrates the skin, as this can promote cracking and delay healing. • Pat dry very gently with a soft paper towel.