2017 Illinois State Rail Plan Update P a G E | 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Amtrak's Rights and Relationships with Host Railroads

Amtrak’s Rights and Relationships with Host Railroads September 21, 2017 Jim Blair –Director Host Railroads Today’s Amtrak System 2| Amtrak Amtrak’s Services • Northeast Corridor (NEC) • 457 miles • Washington‐New York‐Boston Northeast Corridor • 11.9 million riders in FY16 • Long Distance (LD) services • 15 routes • Up to 2,438 miles in length Long • 4.65 million riders in FY16 Distance • State‐supported trains • 29 routes • 19 partner states • Up to 750 miles in length State- • 14.7 million riders in FY16 supported3| Amtrak Amtrak’s Host Railroads Amtrak Route System Track Ownership Excluding Terminal Railroads VANCOUVER SEATTLE Spokane ! MONTREAL PORTLAND ST. PAUL / MINNEAPOLIS Operated ! St. Albans by VIA Rail NECR MDOT TORONTO VTR Rutland ! Port Huron Niagara Falls ! Brunswick Grand Rapids ! ! ! Pan Am MILWAUKEE ! Pontiac Hoffmans Metra Albany ! BOSTON ! CHICAGO ! Springfield Conrail Metro- ! CLEVELAND MBTA SALT LAKE CITY North PITTSBURGH ! ! NEW YORK ! INDIANAPOLIS Harrisburg ! KANSAS CITY ! PHILADELPHIA DENVER ! ! BALTIMORE SACRAMENTO Charlottesville WASHINGTON ST. LOUIS ! Richmond OAKLAND ! Petersburg ! Buckingham ! Newport News Norfolk NMRX Branch ! Oklahoma City ! Bakersfield ! MEMPHIS SCRRA ALBUQUERQUE ! ! LOS ANGELES ATLANTA SCRRA / BNSF / SDN DALLAS ! FT. WORTH SAN DIEGO HOUSTON ! JACKSONVILLE ! NEW ORLEANS SAN ANTONIO Railroads TAMPA! Amtrak (incl. Leased) Norfolk Southern FDOT ! MIAMI Union Pacific Canadian Pacific BNSF Canadian National CSXT Other Railroads 4| Amtrak Amtrak’s Host Railroads ! MONTREAL Amtrak NEC Route System -

GAO-02-398 Intercity Passenger Rail: Amtrak Needs to Improve Its

United States General Accounting Office Report to the Honorable Ron Wyden GAO U.S. Senate April 2002 INTERCITY PASSENGER RAIL Amtrak Needs to Improve Its Decisionmaking Process for Its Route and Service Proposals GAO-02-398 Contents Letter 1 Results in Brief 2 Background 3 Status of the Growth Strategy 6 Amtrak Overestimated Expected Mail and Express Revenue 7 Amtrak Encountered Substantial Difficulties in Expanding Service Over Freight Railroad Tracks 9 Conclusions 13 Recommendation for Executive Action 13 Agency Comments and Our Evaluation 13 Scope and Methodology 16 Appendix I Financial Performance of Amtrak’s Routes, Fiscal Year 2001 18 Appendix II Amtrak Route Actions, January 1995 Through December 2001 20 Appendix III Planned Route and Service Actions Included in the Network Growth Strategy 22 Appendix IV Amtrak’s Process for Evaluating Route and Service Proposals 23 Amtrak’s Consideration of Operating Revenue and Direct Costs 23 Consideration of Capital Costs and Other Financial Issues 24 Appendix V Market-Based Network Analysis Models Used to Estimate Ridership, Revenues, and Costs 26 Models Used to Estimate Ridership and Revenue 26 Models Used to Estimate Costs 27 Page i GAO-02-398 Amtrak’s Route and Service Decisionmaking Appendix VI Comments from the National Railroad Passenger Corporation 28 GAO’s Evaluation 37 Tables Table 1: Status of Network Growth Strategy Route and Service Actions, as of December 31, 2001 7 Table 2: Operating Profit (Loss), Operating Ratio, and Profit (Loss) per Passenger of Each Amtrak Route, Fiscal Year 2001, Ranked by Profit (Loss) 18 Table 3: Planned Network Growth Strategy Route and Service Actions 22 Figure Figure 1: Amtrak’s Route System, as of December 2001 4 Page ii GAO-02-398 Amtrak’s Route and Service Decisionmaking United States General Accounting Office Washington, DC 20548 April 12, 2002 The Honorable Ron Wyden United States Senate Dear Senator Wyden: The National Railroad Passenger Corporation (Amtrak) is the nation’s intercity passenger rail operator. -

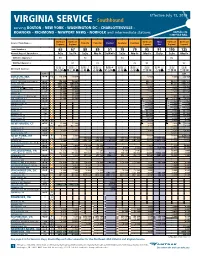

Amtrak Timetables-Virginia Service

Effective July 13, 2019 VIRGINIA SERVICE - Southbound serving BOSTON - NEW YORK - WASHINGTON DC - CHARLOTTESVILLE - ROANOKE - RICHMOND - NEWPORT NEWS - NORFOLK and intermediate stations Amtrak.com 1-800-USA-RAIL Northeast Northeast Northeast Silver Northeast Northeast Service/Train Name4 Palmetto Palmetto Cardinal Carolinian Carolinian Regional Regional Regional Star Regional Regional Train Number4 65 67 89 89 51 79 79 95 91 195 125 Normal Days of Operation4 FrSa Su-Th SaSu Mo-Fr SuWeFr SaSu Mo-Fr Mo-Fr Daily SaSu Mo-Fr Will Also Operate4 9/1 9/2 9/2 9/2 Will Not Operate4 9/1 9/2 9/2 9/2 9/2 R B y R B y R B y R B y R B s R B y R B y R B R s y R B R B On Board Service4 Q l å O Q l å O l å O l å O r l å O l å O l å O y Q å l å O y Q å y Q å Symbol 6 R95 BOSTON, MA ∑w- Dp l9 30P l9 30P 6 10A 6 30A 86 10A –South Station Boston, MA–Back Bay Station ∑v- R9 36P R9 36P R6 15A R6 35A 8R6 15A Route 128, MA ∑w- lR9 50P lR9 50P R6 25A R6 46A 8R6 25A Providence, RI ∑w- l10 22P l10 22P 6 50A 7 11A 86 50A Kingston, RI (b(™, i(¶) ∑w- 10 48P 10 48P 7 11A 7 32A 87 11A Westerly, RI >w- 11 05P 11 05P 7 25A 7 47A 87 25A Mystic, CT > 11 17P 11 17P New London, CT (Casino b) ∑v- 11 31P 11 31P 7 45A 8 08A 87 45A Old Saybrook, CT ∑w- 11 53P 11 53P 8 04A 8 27A 88 04A Springfield, MA ∑v- 7 05A 7 25A 7 05A Windsor Locks, CT > 7 24A 7 44A 7 24A Windsor, CT > 7 29A 7 49A 7 29A Train 495 Train 495 Hartford, CT ∑v- 7 39A Train 405 7 59A 7 39A Berlin, CT >v D7 49A 8 10A D7 49A Meriden, CT >v D7 58A 8 19A D7 58A Wallingford, CT > D8 06A 8 27A D8 06A State Street, CT > q 8 19A 8 40A 8 19A New Haven, CT ∑v- Ar q q 8 27A 8 47A 8 27A NEW HAVEN, CT ∑v- Ar 12 30A 12 30A 4 8 41A 4 9 03A 4 88 41A Dp l12 50A l12 50A 8 43A 9 05A 88 43A Bridgeport, CT >w- 9 29A Stamford, CT ∑w- 1 36A 1 36A 9 30A 9 59A 89 30A New Rochelle, NY >w- q 10 21A NEW YORK, NY ∑w- Ar 2 30A 2 30A 10 22A 10 51A 810 22A –Penn Station Dp l3 00A l3 25A l6 02A l5 51A l6 45A l7 17A l7 25A 10 35A l11 02A 11 05A 11 35A Newark, NJ ∑w- 3 20A 3 45A lR6 19A lR6 08A lR7 05A lR7 39A lR7 44A 10 53A lR11 22A 11 23A 11 52A Newark Liberty Intl. -

Merchants and the Origins of Capitalism

Merchants and the Origins of Capitalism Sophus A. Reinert Robert Fredona Working Paper 18-021 Merchants and the Origins of Capitalism Sophus A. Reinert Harvard Business School Robert Fredona Harvard Business School Working Paper 18-021 Copyright © 2017 by Sophus A. Reinert and Robert Fredona Working papers are in draft form. This working paper is distributed for purposes of comment and discussion only. It may not be reproduced without permission of the copyright holder. Copies of working papers are available from the author. Merchants and the Origins of Capitalism Sophus A. Reinert and Robert Fredona ABSTRACT: N.S.B. Gras, the father of Business History in the United States, argued that the era of mercantile capitalism was defined by the figure of the “sedentary merchant,” who managed his business from home, using correspondence and intermediaries, in contrast to the earlier “traveling merchant,” who accompanied his own goods to trade fairs. Taking this concept as its point of departure, this essay focuses on the predominantly Italian merchants who controlled the long‐distance East‐West trade of the Mediterranean during the Middle Ages and Renaissance. Until the opening of the Atlantic trade, the Mediterranean was Europe’s most important commercial zone and its trade enriched European civilization and its merchants developed the most important premodern mercantile innovations, from maritime insurance contracts and partnership agreements to the bill of exchange and double‐entry bookkeeping. Emerging from literate and numerate cultures, these merchants left behind an abundance of records that allows us to understand how their companies, especially the largest of them, were organized and managed. -

Chicago Union Station Chicago Union Station MASTER DEVELOPER PROCUREMENT OVERVIEW October 2016 July 2015

Next Steps Investing in the Future of Chicago Union Station Chicago Union Station MASTER DEVELOPER PROCUREMENT OVERVIEW October 2016 July 2015 1 Chicago Union Station Operations • 4th busiest station in the Amtrak network; 3.3M passengers in FY15 • Serving more than 300 trains per weekday (Amtrak and Metra) • Serves six of Metra’s eleven routes Planning Goals • Improve circulation and safety • Increase capacity • Enhance customer experience • Improve connectivity Headhouse Building on Corner of Jackson Blvd. and Canal St. Planning Status • Advance near-term improvements from City-led Master Plan • Initiate Master Development Plan Planning Partners • City of Chicago (CDOT), Metra, RTA, IDOT and other stakeholders Great Hall in the Headhouse Building Boarding Lounge in Concourse Building 2 Collaborative Planning Chicago Union Station Master Plan: Released by the Chicago Department of Transportation (CDOT) in May, 2012, in collaboration with Amtrak, Metra, RTA and other local and regional stakeholders. Goals of the study included: • Provision of sufficient capacity for current and future ridership demand. • Improved station access, passenger circulation and customer experience. • Improved connections with local and regional buses, transit, taxis and shuttles. • Creation of a catalyst for growth in Chicago and the region, while attracting nearby private development. CDOT Report Released in May, 2012 Restoration of a prominent civic landmark. Recommended near, mid and long-term improvement projects with an estimated program cost of approx. $500M. 3 Phase 1A Overview Phase 1A, the preliminary engineering work for Phase 1 improvement projects, at a cost of $6 million, consists of planning, historic review and preliminary engineering tasks, up to 30% design. In addition, the projects envisioned for Phase 1, in its entirety, is projected to cost in excess of $200 million. -

R0202'11 LSB Research Services Division MG

Rep. McCann offered the following concurrent resolution: House Concurrent Resolution No. 41. A concurrent resolution to urge the National Railroad Passenger Corporation (Amtrak) to pursue bicycle friendly policies by providing for bicycles on board trains and bicycle parking in future station plans. Whereas, An efficient, modern, transportation system is a pillar of a healthy economic climate and vital for Michigan's future. All modes of 21st century transportation infrastructure should be made accessible to modern travelers, whether tourists or commuters. Seamless multi-modal connections are essential to facilitate tourism and to allow greater mobility for bike commuters and those without cars. Bicyclists should be able to switch between transportation modes and link trips by bringing bicycles on trains without having to check them as boxed luggage. Bicycle tourism and commuting would be further accommodated with short and long-term bike parking at Amtrak stations. Unfortunately, Amtrak does not allow bicycles on board Michigan routes at this time and bike parking is not always available; and Whereas, Amtrak's routes out of Chicago, the Downstate Illinois Service and Missouri River Runner, offer roll-on bike service; the option to bring bicycles on board, either by storing bikes on board in bike racks, or secured as checked baggage with tie-down equipment (not in a box), and allow folding bicycles on board as carry-on baggage. All three of the Michigan Amtrak routes, The Blue Water, Lake Shore Limited and Pere Marquette lines, use the same equipment as Chicago area trains and would only have to update the reservations system to allow bikes on board in Michigan; and Whereas, Bicycle tourism is a booming industry and many Michigan bike tour events are located in or near cities accessible by Amtrak service. -

Records Relating to Railroads in the Cartographic Section of the National Archives

REFERENCE INFORMATION PAPER 116 Records Relating to Railroads in the Cartographic Section of the national archives 1 Records Relating to Railroads in the Cartographic Section of the National Archives REFERENCE INFORMATION PAPER 116 National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, DC Compiled by Peter F. Brauer 2010 United States. National Archives and Records Administration. Records relating to railroads in the cartographic section of the National Archives / compiled by Peter F. Brauer.— Washington, DC : National Archives and Records Administration, 2010. p. ; cm.— (Reference information paper ; no 116) includes index. 1. United States. National Archives and Records Administration. Cartographic and Architectural Branch — Catalogs. 2. Railroads — United States — Armed Forces — History —Sources. 3. United States — Maps — Bibliography — Catalogs. I. Brauer, Peter F. II. Title. Cover: A section of a topographic quadrangle map produced by the U.S. Geological Survey showing the Union Pacific Railroad’s Bailey Yard in North Platte, Nebraska, 1983. The Bailey Yard is the largest railroad classification yard in the world. Maps like this one are useful in identifying the locations and names of railroads throughout the United States from the late 19th into the 21st century. (Topographic Quadrangle Maps—1:24,000, NE-North Platte West, 1983, Record Group 57) table of contents Preface vii PART I INTRODUCTION ix Origins of Railroad Records ix Selection Criteria xii Using This Guide xiii Researching the Records xiii Guides to Records xiv Related -

Rainready Calumet Corridor, IL Plan

RainReady Calumet Corridor, IL Plan RainReady Calumet Corridor, IL Plan PREPARED BY THE CENTER FOR NEIGHBORHOOD TECHNOLOGY AND THE U.S. ARMY CORPS OF ENGINEERS MARCH 2017 ©2017 CENTER FOR NEIGHBORHOOD TECHNOLOGY EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 VILLAGE OF ROBBINS Purpose of the RainReady Plan 1 A Citizen’s Guide to a RainReady Robbins i The Problem 2 The Path Ahead 3 VILLAGE OF ROBBINS How to Use This Plan 4 COMMUNITY SNAPSHOT 1 INTRODUCTION 5 ROBBINS, IL AT A GLANCE 2 The Vision 5 Flooding Risks and Resilience Opportunities 3 THE PROBLEM 6 RAINREADY ROBBINS COMMUNITY SURVEY 8 CAUSES AND IMPACTS OF URBAN FLOODING 10 EXISTING CONDITIONS IN ROBBINS, IL Your Homes and Neighborhoods 10 THE PATH FORWARD 23 Your Business Districts and Shopping Centers 12 What Can We Do? 23 Your Industrial Centers and How to Approach Financing Transportation Corridors 14 RainReady Communities 26 Your Open Space and Natural Areas 16 Community Assets 18 PARTNERS AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 29 Steering Committees 30 COMMUNITY PRIORITIES 20 Technical Advisory Committee 33 Non-TAC Advisors 33 RAINREADY ACTION PLAN 22 THE PLANNING PROCESS 34 Purpose of the RainReady Plan 34 RAINREADY ROBBINS IMPLEMENTATION PLAN Planning and Outreach Approach 36 Goal 1: Reorient 24 Goal 2: Repair 28 REGIONAL CONTEXT 42 Goal 3: Retrofit 31 RAINREADY: REGULATORY ENVIRONMENT SUMMARY 50 RAINREADY SOLUTIONS GOALS, STRATEGIES, AND ACTIONS 55 A RainReady Future is Possible! 55 RAINREADY GOALS 56 The Three R’s: Reorient, Repair, Retrofit 56 THE THREE R’S 61 GOALS, STRATEGIES, AND ACTIONS 62 Goal 1: Reorient 64 Goal 2: Repair 66 Goal 3: Retrofit 67 RAINREADY CALUMET CORRIDOR PLAN EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Purpose of the RainReady Plan From more intense storms and chronic urban flooding to economic constraints and aging infrastructure, communities across the nation must find ways to thrive in the midst of shocks and stresses. -

CAPITOL LIMITED Train Time Schedule & Line Route

CAPITOL LIMITED train time schedule & line map Capitol Limited View In Website Mode The train line Capitol Limited has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Chicago Union Station: 4:05 PM (2) Washington Union Station: 7:40 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest CAPITOL LIMITED train station near you and ƒnd out when is the next CAPITOL LIMITED train arriving. Direction: Chicago Union Station CAPITOL LIMITED train Time Schedule 16 stops Chicago Union Station Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 4:05 PM Monday 4:05 PM Union Station 50 Massachusetts Avenue Ne, Washington Tuesday 4:05 PM Rockville Amtrak Wednesday 4:05 PM 250 Rockville Pike, Rockville Thursday 4:05 PM Harpers Ferry Amtrak Friday 4:05 PM 182 Potomac St, Harpers Ferry Saturday 4:05 PM Martinsburg Amtrak Station 229 East Martin Street, Berkeley County Cumberland Amtrak Station 200 Park St, Cumberland CAPITOL LIMITED train Info Direction: Chicago Union Station Connellsville Amtrak Stops: 16 Trip Duration: 1060 min Pittsburgh Amtrak Station Line Summary: Union Station, Rockville Amtrak, 1100 Liberty Avenue, Pittsburgh Harpers Ferry Amtrak, Martinsburg Amtrak Station, Cumberland Amtrak Station, Connellsville Amtrak, Alliance Amtrak Pittsburgh Amtrak Station, Alliance Amtrak, Cleveland, Elyria Amtrak, Sandusky Amtrak Station, Cleveland Toledo, Waterloo Amtrak Station, Elkhart Amtrak 200 Cleveland Memorial Shoreway, Cleveland Station, South Bend Amtrak Station, Chicago Union Station Elyria Amtrak 410 East River Road, Elyria Sandusky Amtrak Station -

Annual Report for the As a Result of the National Financial Environment, Throughout 2009, US Congress Calendar Year 2009, Pursuant to Section 43 of the Banking Law

O R K Y S T W A E T E N 2009 B T A ANNUAL N N E K M REPORT I N T G R D E P A WWW.BANKING.STATE.NY.US 1-877-BANK NYS One State Street Plaza New York, NY 10004 (212) 709-3500 80 South Swan Street Albany, NY 12210 (518) 473-6160 333 East Washington Street Syracuse, NY 13202 (315) 428-4049 September 15, 2010 To the Honorable David A. Paterson and Members of the Legislature: I hereby submit the New York State Banking Department Annual Report for the As a result of the national financial environment, throughout 2009, US Congress calendar year 2009, pursuant to Section 43 of the Banking Law. debated financial regulatory reform legislation. While the regulatory debate developed on the national stage, the Banking Department forged ahead with In 2009, the New York State Banking Department regulated more than 2,700 developing and implementing new state legislation and regulations to address financial entities providing services in New York State, including both depository the immediate crisis and avoid a similar crisis in the future. and non-depository institutions. The total assets of the depository institutions supervised exceeded $2.2 trillion. State Regulation: During 2009, what began as a subprime mortgage crisis led to a global downturn As one of the first states to identify the mortgage crisis, New York was fast in economic activity, leading to decreased employment, decreased borrowing to act on developing solutions. Building on efforts from 2008, in December and spending, and a general contraction in the financial industry as a whole. -

Chicago-South Bend-Toledo-Cleveland-Erie-Buffalo-Albany-New York Frequency Expansion Report – Discussion Draft 2 1

Chicago-South Bend-Toledo-Cleveland-Erie-Buffalo- Albany-New York Frequency Expansion Report DISCUSSION DRAFT (Quantified Model Data Subject to Refinement) Table of Contents 1. Project Background: ................................................................................................................................ 3 2. Early Study Efforts and Initial Findings: ................................................................................................ 5 3. Background Data Collection Interviews: ................................................................................................ 6 4. Fixed-Facility Capital Cost Estimate Range Based on Existing Studies: ............................................... 7 5. Selection of Single Route for Refined Analysis and Potential “Proxy” for Other Routes: ................ 9 6. Legal Opinion on Relevant Amtrak Enabling Legislation: ................................................................... 10 7. Sample “Timetable-Format” Schedules of Four Frequency New York-Chicago Service: .............. 12 8. Order-of-Magnitude Capital Cost Estimates for Platform-Related Improvements: ............................ 14 9. Ballpark Station-by-Station Ridership Estimates: ................................................................................... 16 10. Scoping-Level Four Frequency Operating Cost and Revenue Model: .................................................. 18 11. Study Findings and Conclusions: ......................................................................................................... -

CP's North American Rail

2020_CP_NetworkMap_Large_Front_1.6_Final_LowRes.pdf 1 6/5/2020 8:24:47 AM 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Lake CP Railway Mileage Between Cities Rail Industry Index Legend Athabasca AGR Alabama & Gulf Coast Railway ETR Essex Terminal Railway MNRR Minnesota Commercial Railway TCWR Twin Cities & Western Railroad CP Average scale y y y a AMTK Amtrak EXO EXO MRL Montana Rail Link Inc TPLC Toronto Port Lands Company t t y i i er e C on C r v APD Albany Port Railroad FEC Florida East Coast Railway NBR Northern & Bergen Railroad TPW Toledo, Peoria & Western Railway t oon y o ork éal t y t r 0 100 200 300 km r er Y a n t APM Montreal Port Authority FLR Fife Lake Railway NBSR New Brunswick Southern Railway TRR Torch River Rail CP trackage, haulage and commercial rights oit ago r k tland c ding on xico w r r r uébec innipeg Fort Nelson é APNC Appanoose County Community Railroad FMR Forty Mile Railroad NCR Nipissing Central Railway UP Union Pacic e ansas hi alga ancou egina as o dmon hunder B o o Q Det E F K M Minneapolis Mon Mont N Alba Buffalo C C P R Saint John S T T V W APR Alberta Prairie Railway Excursions GEXR Goderich-Exeter Railway NECR New England Central Railroad VAEX Vale Railway CP principal shortline connections Albany 689 2622 1092 792 2636 2702 1574 3518 1517 2965 234 147 3528 412 2150 691 2272 1373 552 3253 1792 BCR The British Columbia Railway Company GFR Grand Forks Railway NJT New Jersey Transit Rail Operations VIA Via Rail A BCRY Barrie-Collingwood Railway GJR Guelph Junction Railway NLR Northern Light Rail VTR