Sentence-Final Expressions in the Japanese Popular Mediascape

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Roots of Middle-Earth: William Morris's Influence Upon J. R. R. Tolkien

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 12-2007 The Roots of Middle-Earth: William Morris's Influence upon J. R. R. Tolkien Kelvin Lee Massey University of Tennessee - Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Recommended Citation Massey, Kelvin Lee, "The Roots of Middle-Earth: William Morris's Influence upon J. R. R. olkien.T " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 2007. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/238 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Kelvin Lee Massey entitled "The Roots of Middle-Earth: William Morris's Influence upon J. R. R. olkien.T " I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in English. David F. Goslee, Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: Thomas Heffernan, Michael Lofaro, Robert Bast Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Kelvin Lee Massey entitled “The Roots of Middle-earth: William Morris’s Influence upon J. -

Japanese Native Speakers' Attitudes Towards

JAPANESE NATIVE SPEAKERS’ ATTITUDES TOWARDS ATTENTION-GETTING NE OF INTIMACY IN RELATION TO JAPANESE FEMININITIES THESIS Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree Master of Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Atsuko Oyama, M.E. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2008 Master’s Examination Committee: Approved by Professor Mari Noda, Advisor Professor Mineharu Nakayama Advisor Professor Kathryn Campbell-Kibler Graduate Program in East Asian Languages and Literatures ABSTRACT This thesis investigates Japanese people’s perceptions of the speakers who use “attention-getting ne of intimacy” in discourse in relation to femininity. The attention- getting ne of intimacy is the particle ne that is used within utterances with a flat or a rising intonation. It is commonly assumed that this attention-getting ne is frequently used by children as well as women. Feminine connotations attached to this attention-getting ne when used by men are also noted. The attention-getting ne of intimacy is also said to connote both intimate and over-friendly impressions. On the other hand, recent studies on Japanese femininity have proposed new images that portrays figures of immature and feminine women. Assuming the similarity between the attention-getting ne and new images of Japanese femininity, this thesis aims to reveal the relationship between them. In order to investigate listeners’ perceptions of women who use the attention- getting ne of intimacy with respect to femininity, this thesis employs the matched-guise technique as its primary methodological choice using the presence of attention-getting ne of intimacy as its variable. In addition to the implicit reactions obtained in the matched- guise technique, people’s explicit thoughts regarding being onnarashii ‘womanly’ and kawairashii ‘endearing’ were also collected in the experiment. -

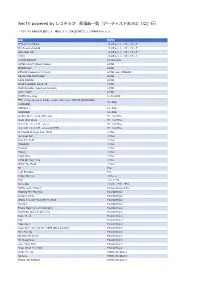

Rectv Powered by レコチョク 配信曲 覧(アーティスト名ヨミ「は」 )

RecTV powered by レコチョク 配信曲⼀覧(アーティスト名ヨミ「は」⾏) ※2021/7/19時点の配信曲です。時期によっては配信が終了している場合があります。 曲名 歌手名 アワイロサクラチル バイオレント イズ サバンナ It's Power of LOVE バイオレント イズ サバンナ OH LOVE YOU バイオレント イズ サバンナ つなぐ バイオレント イズ サバンナ I'M DIFFERENT HI SUHYUN AFTER LIGHT [Music Video] HYDE INTERPLAY HYDE ZIPANG (Japanese Version) HYDE feat. YOSHIKI BELIEVING IN MYSELF HYDE FAKE DIVINE HYDE WHO'S GONNA SAVE US HYDE MAD QUALIA [Japanese Version] HYDE LET IT OUT HYDE 数え切れないKiss Hi-Fi CAMP 雲の上 feat. Keyco & Meika, Izpon, Take from KOKYO [ACOUSTIC HIFANA VERSION] CONNECT HIFANA WAMONO HIFANA A Little More For A Little You ザ・ハイヴス Walk Idiot Walk ザ・ハイヴス ティック・ティック・ブーン ザ・ハイヴス ティック・ティック・ブーン(ライヴ) ザ・ハイヴス If I Could Change Your Mind ハイム Summer Girl ハイム Now I'm In It ハイム Hallelujah ハイム Forever ハイム Falling ハイム Right Now ハイム Little Of Your Love ハイム Want You Back ハイム BJ Pile Lost Paradise Pile I Was Wrong バイレン 100 ハウィーD Shine On ハウス・オブ・ラヴ Battle [Lyric Video] House Gospel Choir Waiting For The Sun Powderfinger Already Gone Powderfinger (Baby I've Got You) On My Mind Powderfinger Sunsets Powderfinger These Days [Live In Concert] Powderfinger Stumblin' [Live In Concert] Powderfinger Take Me In Powderfinger Tail Powderfinger Passenger Powderfinger Passenger [Live At The 1999 ARIA Awards] Powderfinger Pick You Up Powderfinger My Kind Of Scene Powderfinger My Happiness Powderfinger Love Your Way Powderfinger Reap What You Sow Powderfinger Wake We Up HOWL BE QUIET fantasia HOWL BE QUIET MONSTER WORLD HOWL BE QUIET 「いくらだと思う?」って聞かれると緊張する(ハタリズム) バカリズムと アステリズム HaKU 1秒間で君を連れ去りたい HaKU everything but the love HaKU the day HaKU think about you HaKU dye it white HaKU masquerade HaKU red or blue HaKU What's with him HaKU Ice cream BACK-ON a day dreaming.. -

浜崎あゆみ Next Level Mp3, Flac, Wma

浜崎あゆみ Next Level mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Electronic / Rock / Pop Album: Next Level Country: Japan Released: 2009 Style: J-pop, Techno, Pop Rock, Synth-pop MP3 version RAR size: 1324 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1492 mb WMA version RAR size: 1405 mb Rating: 4.9 Votes: 778 Other Formats: DXD VOC VQF AU AUD AIFF XM Tracklist Hide Credits Bridge To The Sky 1 1:40 Music By, Arranged By, Programmed By – Yuta Nakano Next Level 2 Arranged By, Programmed By – HAL Backing Vocals – Junko HirotaniGuitar – Takehito 4:28 ShimizuMusic By – D.A.I.Programmed By [Additional] – Mayuko Maruyama Disco-munication 3 1:30 Music By, Arranged By, Programmed By, Guitar, Bass – CMJK Energize 4 4:29 Arranged By, Programmed By, Guitar – CMJKMusic By – Yuta Nakano Sparkle 5 4:30 Arranged By, Programmed By, Guitar, Bass – CMJKMusic By – Kazuhiro Hara Rollin' 6 5:02 Arranged By, Programmed By, Guitar – CMJKMusic By – Yuta Nakano Green 7 Arranged By [Strings] – Gen IttetsuArranged By, Programmed By, Guitar – TasukuDrums – 4:46 Tom Tamada*Music By – Tetsuya YukumiStrings – Gen Ittetsu Strings* Load Of The Shugyo 8 1:30 Music By, Arranged By, Programmed By, Guitar, Bass – CMJK Identity Backing Vocals [Additional] – Sharlotte Gibson, Stephanie AlexandraBass – Chris 9 4:16 ChaneyDrums – Josh FreeseGuitar – Tim PierceGuitar [Additional] – KIKU , Ryota AkizukiMusic By, Arranged By, Programmed By – Yuta Nakano Rule Arranged By, Programmed By – HAL Bass – Junko KitasakaDrums – Tom Tamada*Guitar – 10 4:07 Takehito ShimizuMusic By – Miki WatanabeProgrammed -

The Globalization of K-Pop: the Interplay of External and Internal Forces

THE GLOBALIZATION OF K-POP: THE INTERPLAY OF EXTERNAL AND INTERNAL FORCES Master Thesis presented by Hiu Yan Kong Furtwangen University MBA WS14/16 Matriculation Number 249536 May, 2016 Sworn Statement I hereby solemnly declare on my oath that the work presented has been carried out by me alone without any form of illicit assistance. All sources used have been fully quoted. (Signature, Date) Abstract This thesis aims to provide a comprehensive and systematic analysis about the growing popularity of Korean pop music (K-pop) worldwide in recent years. On one hand, the international expansion of K-pop can be understood as a result of the strategic planning and business execution that are created and carried out by the entertainment agencies. On the other hand, external circumstances such as the rise of social media also create a wide array of opportunities for K-pop to broaden its global appeal. The research explores the ways how the interplay between external circumstances and organizational strategies has jointly contributed to the global circulation of K-pop. The research starts with providing a general descriptive overview of K-pop. Following that, quantitative methods are applied to measure and assess the international recognition and global spread of K-pop. Next, a systematic approach is used to identify and analyze factors and forces that have important influences and implications on K-pop’s globalization. The analysis is carried out based on three levels of business environment which are macro, operating, and internal level. PEST analysis is applied to identify critical macro-environmental factors including political, economic, socio-cultural, and technological. -

Review of the Scottish Animation Sector

__ Review of the Scottish Animation Sector Creative Scotland BOP Consulting March 2017 Page 1 of 45 Contents 1. Executive Summary ........................................................................... 4 2. The Animation Sector ........................................................................ 6 3. Making Animation ............................................................................ 11 4. Learning Animation .......................................................................... 21 5. Watching Animation ......................................................................... 25 6. Case Study: Vancouver ................................................................... 27 7. Case Study: Denmark ...................................................................... 29 8. Case Study: Northern Ireland ......................................................... 32 9. Future Vision & Next Steps ............................................................. 35 10. Appendices ....................................................................................... 39 Page 2 of 45 This Report was commissioned by Creative Scotland, and produced by: Barbara McKissack and Bronwyn McLean, BOP Consulting (www.bop.co.uk) Cover image from Nothing to Declare courtesy of the Scottish Film Talent Network (SFTN), Studio Temba, Once Were Farmers and Interference Pattern © Hopscotch Films, CMI, Digicult & Creative Scotland. If you would like to know more about this report, please contact: Bronwyn McLean Email: [email protected] Tel: 0131 344 -

Aya Hirano Bouken Desho Desho? Mp3, Flac, Wma

Aya Hirano Bouken Desho Desho? mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Pop / Stage & Screen Album: Bouken Desho Desho? Country: US Released: 2007 Style: J-pop, Karaoke, Theme MP3 version RAR size: 1330 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1975 mb WMA version RAR size: 1606 mb Rating: 4.5 Votes: 251 Other Formats: MIDI WAV MMF FLAC APE DXD VQF Tracklist 1 Bouken Desho Desho? 4:18 2 Kazeyomi Ribbon 3:47 3 Bouken Desho Desho? (Karaoke Version) 4:18 4 Kazeyomi Ribbon (Karaoke Version) 3:43 Companies, etc. Recorded At – Studio Magic Garden Credits Arranged By – Junpei Fujita (tracks: 1, 3), Takahiro Ando (tracks: 2, 4) Art Direction – Junya Imai Composed By – Akiko Tomita (tracks: 1, 3), Morihiro Suzuki (tracks: 2, 4) Directed By – Shigeru Saito Engineer – Atsushi Kobayashi , Haruhiko Shimokawa, Katsumi Moriya Executive-Producer – Kazuoki Ohnishi, Shunji Inoue Illustration – Shoko Ikeda Lyrics By – Aki Hata Mastered By – Yoshihiko Ando Painting – Naomi Ishida Photography By – Takahiro Yoshimoto Producer – Shigeru Saito Strings – Gen Ittetsu Strings* Tenor Saxophone – Kazuki Katsuta Trombone – Hiroki Sato Trumpet – Shirou Sasaki* Notes Tracks 1 and 3 are opening theme of TV anime "The Melancholy of Haruhi Suumiya". Tracks 2 and 4 are opening theme of radio drama "The Melancholy of Haruhi Suzumiya SOS Brigade Radio Division". Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year LACM-4255 Aya Hirano 冒険でしょでしょ? (CD, Maxi) Lantis LACM-4255 Japan 2006 Related Music albums to Bouken Desho Desho? by Aya Hirano Masayoshi Takanaka - T-Wave 山瀬まみ - 親指姫 Koda Kumi - Eternity ~Love & Songs~ Ai Otsuka - Love Is Best Taeko Ohnuki, Shigeru Suzuki, Haruomi Hosono, Kaze , Yuko Tomita, Ryohei Yamanashi, Haruomi Hosono - On The Beach Ayumi Hamasaki - A Ballads Takahiro Saito - Mandom-Lovers Of The World / 25 Minutes To Go Ayumi Hamasaki - Ayu-mi-x 7 -Version Acoustic Orchestra- Ai Otsuka - Love Fantastic Various - Carol Tribute Sam Morgan's Jazz Band / The Get-Happy Band / The Blue Ribbon Syncopators - Sam Morgan Etc. -

Visual Metaphors on Album Covers: an Analysis Into Graphic Design's

Visual Metaphors on Album Covers: An Analysis into Graphic Design’s Effectiveness at Conveying Music Genres by Vivian Le A THESIS submitted to Oregon State University Honors College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Honors Baccalaureate of Science in Accounting and Business Information Systems (Honors Scholar) Presented May 29, 2020 Commencement June 2020 AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Vivian Le for the degree of Honors Baccalaureate of Science in Accounting and Business Information Systems presented on May 29, 2020. Title: Visual Metaphors on Album Covers: An Analysis into Graphic Design’s Effectiveness at Conveying Music Genres. Abstract approved:_____________________________________________________ Ryann Reynolds-McIlnay The rise of digital streaming has largely impacted the way the average listener consumes music. Consequentially, while the role of album art has evolved to meet the changes in music technology, it is hard to measure the effect of digital streaming on modern album art. This research seeks to determine whether or not graphic design still plays a role in marketing information about the music, such as its genre, to the consumer. It does so through two studies: 1. A computer visual analysis that measures color dominance of an image, and 2. A mixed-design lab experiment with volunteer participants who attempt to assess the genre of a given album. Findings from the first study show that color scheme models created from album samples cannot be used to predict the genre of an album. Further findings from the second theory show that consumers pay a significant amount of attention to album covers, enough to be able to correctly assess the genre of an album most of the time. -

Barticle's Japanese Mahjong Guide Page 1 Jump To: Contents 2

1. Introduction 9. Yakuman 15. Optional Hands 2. Equipment ○ Single Yakuman ○ Optional Yaku ○ Tiles ○ Double Yakuman ○ Optional Yakuman 3. Format and Winds ○ Related Terms 16. Optional Rules ○ Preliminaries and Seating 10. Dora 17. Miscellaneous ○ Game Format 11. Ready and Waiting 18. Reference 4. Process of Play ○ Basic Waits ○ Yaku Summary 5. Sets and Calling ○ Complex Waits ○ Yakuman Summary ○ Sets ○ Furiten and Defence ○ Scoring Tables ○ Calling 12. Win, Lose or Draw ○ Limits ○ Open and Closed ○ Wins ○ Numbers 6. Yaku (Part 1) ○ Exhaustive Draws ○ Final Scores ○ Common Yaku ○ Abortive Draws ○ Gaming ○ Related Terms 13. Scoring 19. Japanese 7. Reaching ○ Calculation ○ Scripts ○ Limits ○ Pronunciation 8. Yaku (Part 2) ○ Related Terms ○ Uncommon Yaku 20. Credits and Legal 14. Penalties ○ Thanks Endorsed and hosted by the United States Professional Mahjong League 1. Introduction This is a guide to the modern Japanese version of the traditional four-player Chinese tabletop game of mahjong, this variant also being known as Riichi Mahjong or Reach Mahjong. I've previously written several guides to specific mahjong video-games (these can all be accessed from my GameFAQs contributor page) but I decided to produce a new, general, resource which will be useful to people playing on any mahjong video-game or website, reading mahjong manga, watching mahjong anime or perhaps even playing the game with real tiles! Since I've already included lists of mahjong terms in some of my previous guides and I want to place an emphasis on explaining the terminology used in the game, I've decided to produce this in the form of a non-alphabetical glossary, with detailed definitions for each entry, terms given in Japanese text, categorised sections and hyperlinks between them. -

With One Voice Community Choir Program

WITH ONE VOICE COMMUNITY CHOIR PROGRAM We hope being part of this choir program will bring you great joy, new connections, friendships, opportunities, new skills and an improved sense of wellbeing and even a job if you need one! You will also feel the creative satisfaction of performing at some wonderful festivals and events. If you have any friends, family or colleagues who would also like to get involved, please give them Creativity Australia’s details, which can be found on the inside of the front cover of this booklet. We hope the choir will grow to be a part of your life for many years. Also, do let us know of any performance or event opportunities for the choir so we can help them come to fruition. We would like to thank all our partners and supporters and ask that you will consider supporting the participation of others in your choir. Published by Creativity Australia. Please give us your email address and we will send you regular choir updates. Prepared by: Shaun Islip – With One Voice Conductor In the meantime, don’t forget to check out our website: www. Kym Dillon – With One Voice Conductor creativityaustralia.org.au Bridget a’Beckett – With One Voice Conductor Andrea Khoza – With One Voice Conductor Thank you for your participation and we are looking forward to a very Marianne Black – With One Voice Conductor exciting and rewarding creative journey together! Tania de Jong – Creativity Australia, Founder & Chair Ewan McEoin – Creativity Australia, General Manager Yours in song, Amy Scott – Creativity Australia, Program Coordinator -

Japanese Gendered Language, Idols, and the Ideal Female Romantic Partner Jacqueline Huaman Professor Kaori Idemaru June 8, 2018

Japanese Gendered Language, Idols, and the Ideal Female Romantic Partner Jacqueline Huaman Professor Kaori Idemaru June 8, 2018 1 1. Introduction Linguists have long studied and debated the nature of gendered language in Japanese: is it a language reality or does it exist only as a language ideal? Many studies have yielded results that indicate that gendered language is used less by Japanese speakers in average conversation than it is used in the media, suggesting that the use of gendered language is more of an ideal than a reality. When it is used in everyday speech, its use is usually connotational and not based on the speaker’s gender. However, studies also show that the use or non-use of certain styles of speaking and gendered markers are used to cultivate identities in real life Japanese society. For example, Dubuc (2012) conducted a study of the language used by Japanese women in managerial positions, which revealed that these women carefully cultivated their language in a way that exerted the authority required by a manager in a business setting without overstepping the boundaries of how women are meant to speak according to Japanese social norms. Even if gendered language functions as a type of language ideal, it is evident by studies such as this that these language norms are prevalent factors that influence how language is viewed in real life social situations and within social hierarchies. As such, it is useful to investigate what gendered language ideals are present today. Though understudied in this field, the genre of idol music in Japan would make an excellent and insightful place to further investigate the implications of the gendered language features present in the media. -

Level 2 Kanji List

Level 2 Kanji List S.No Kanji Readings Meanings Examples 246 相 SOU , SHOU each other , 首相 shu shou - prime minister そ う , し ょ う mutual , 相合傘 ai ai gasa - 2 people sharing an umbrella ai appearance , 相変わらず ai ka warazu - same as always; あ い aspect same ole same ole... minister of state 相撲 sumou - Sumo (has a special su sound 247 愛 love 愛している - I love you! 愛妻 ai sai - beloved wife ai 愛知県 ai chi ken - Aichi prefecture あ い 愛読 ai doku - a Book lover 248 合 GOU , KATSU to be together; 相合傘 ai ai gasa - 2 people sharing an umbrella ゴ ウ , カ ツ to fit 場合 ba ai - a case, situation au 具合 gu ai - condition (of various things) あ う 都合 tsu gou - circumstances, condition, convenience 249 商 SHOU to sell; trade 商港 shou kou - a trade port し ょ う 商業 shou gyou - commerce, business akinau あ き な う 250 浅 SEN shallow, 経験が浅い kei ken ga asai - have little experience せ ん superficial 浅緑 asa midori - light green, pale green asai あ さ い www.thejapanesepage.com 1 Level 2 Kanji List 251 預 YO to keep , 預け金 azuke kin - key money よ to take charge of 預言 yo gen - a prophecy azukaru , azukeru to deposit あ ず か る , あ ず け る 252 汗 KAN sweat , 汗 ase - sweat か ん perspiration 汗腺 kan sen - sweat gland ase あ せ 253 遊 YUU play; to be idle 遊園地 yuu en chi - an amusement park ゆ う 遊星 yuu sei - a planet asobu 遊牧民 yuu boku min - nomad あ そ ぶ 夢遊病 mu yuu byou - sleepwalking 254 値 CHI value, price 価値 ka chi - worth, value ち atai , ne あ た い , ね 255 与 YO to give , award , 与える ataeru - to give, to present よ cause , ataeru to assign (a task) あ た え る www.thejapanesepage.com 2 Level 2 Kanji List 256 温 ON warm , 気温 ki on - temperature お ん temperature 温泉 on sen - Onsen, hot spring atatakai 温度 on do - temperature (degree) あ た た か い 257 暖 DAN warm , 地球温暖化 chi kyuu on dan ka - global warming だ ん cordial 暖まる atatamaru - to warm up; warm oneself atatakai あ た た か い 258 頭 TOU , ZU head , top 石頭 ishi atama - hard headed person (stone head) と う , ず 赤頭巾 aka zu kin - Little Red Riding Hood atama (lit.